What is aquaculture? It may be the solution to overfishing.

From seaweed to shellfish, this fast-growing industry is ensuring that humans have enough protein for our diets. Here's what to know about aquaculture.

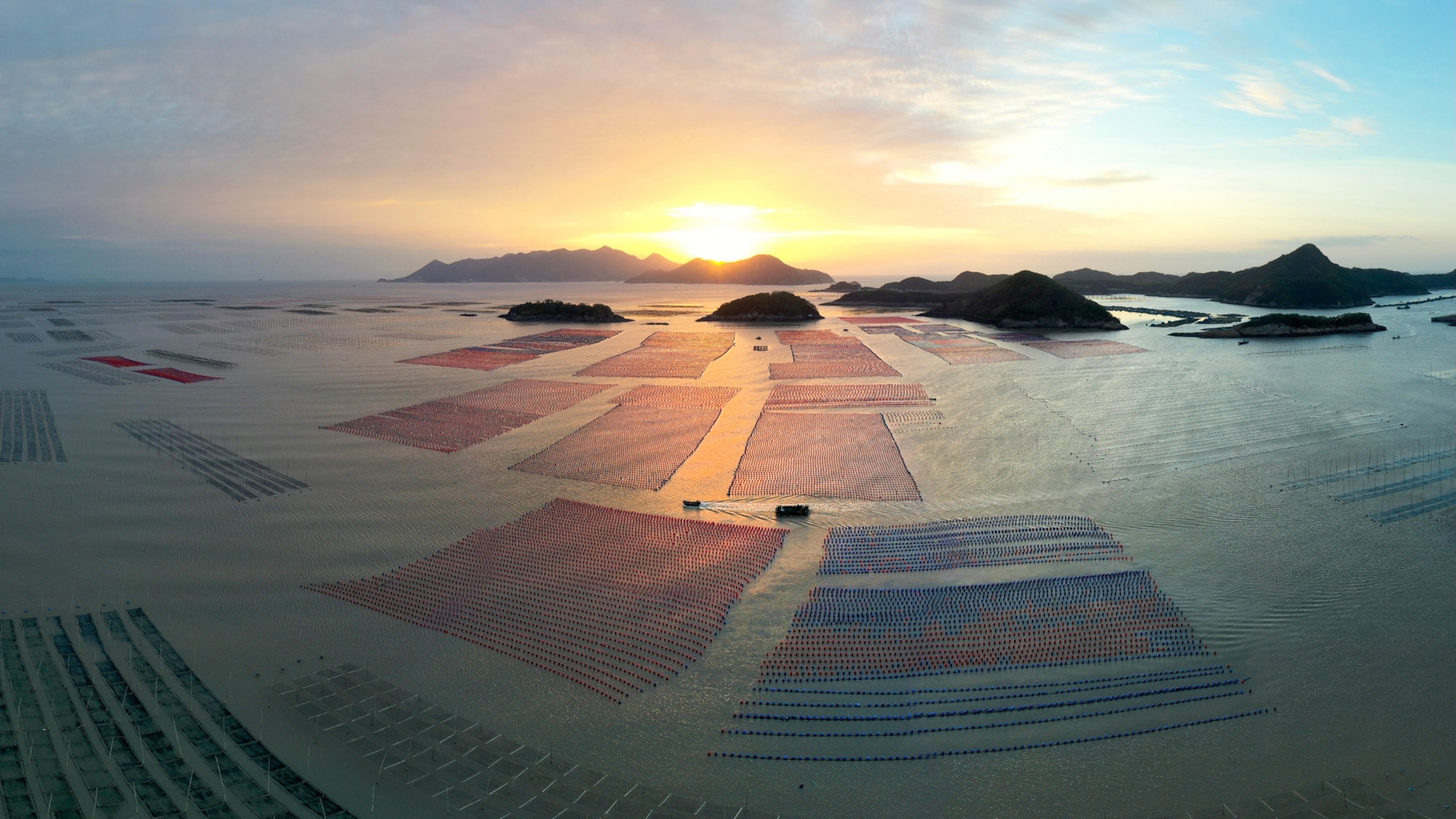

Fishermen and farmers alike are taking to the waters to produce protein to feed the world—from finfish to shellfish to seaweed.

Aquaculture, sometimes called aquafarming, is the breeding, raising, growing, and harvesting of aquatic organisms in fresh and salt water for human consumption and conservation alike—and the nuances of what it entails are vast.

Dating back more than 4,000 years, aquaculture gradually expanded from China to the rest of the world, and has gained most of its popularity in the 21st century. Today, it’s the fastest growing industry for producing protein, one of the basic building blocks of our diet.

Plus, over 50 percent of the world’s seafood comes from aquaculture.

“The debate is over,” says Daniel Benetti, the director of aquaculture at the University of Miami. “It's here to stay. It's already mainstream.”

As overfishing threatens the world’s waters and the species that rely on them, aquaculture may be the solution to keep fishermen at sea and food on our tables. And there are many different types of aquaculture. Here’s what you need to know.

Algae (seaweed) aquaculture

Although Asia is the world’s largest producer of algae, these farms are gaining traction across the world as our understanding of its nutritious value grows.

Seaweed, a type of algae, is also particularly easy to grow as it doesn’t require much attention beyond a little TLC. Sugar kelp, the most commonly cultivated seaweed in the U.S., is grown mainly on longlines, or horizontal ropes, studded with spores that are submerged several feet below the water’s surface. It’s a fast growing, annual crop and has a two-month harvesting window.

When it’s ready, farmers harvest the seaweed by pulling up the longlines and cutting it off. Sugar kelp is mostly sold fresh and directly to restaurants.

Experts say there’s little disadvantage to seaweed farming. “Seaweed farming, and all marine aquaculture, produces far less carbon emissions when compared to terrestrial farming and livestock production,” says Anoushka Concepcion, an assistant extension educator in marine aquaculture at the University of Connecticut.

(Why seaweed “forests” might be the key to neutralizing carbon emissions.)

Shellfish aquaculture

Whether it’s oysters, clams, or mussels, aquaculture helps ensure there’s plenty of fresh shellfish available to us to eat—and they help keep our oceans clean.

Farmers obtain shellfish seedlings from a hatchery, which is where the shellfish are bred from sperm to larvae to a plantable size. Once in a farm, shellfish, like seaweed, don’t require farmers to provide any food or fertilizer beyond what the ocean naturally offers. Farmers do, however, use different methods to grow each type of shellfish.

(Your love for fresh oysters can help the planet.)

Mussels: Most grow mussels at the top of the water on ropes that hang down from a floating barge or structure. The lines are covered with mussel seed and then placed in the water, where they’ll grow to market size in about two years.

Oysters: Some farmers cultivate oysters in bags or cages that float at the top of the water, while others string lines below the water’s surface, almost like a suspended clothesline hung with oyster bags. These shellfish can also be grown uncaged or in bags on the sea floor.

Clams: Clams are exclusively bottom-cultured creatures, meaning they’ll burrow themselves on the water’s floor, either loose or in bags.

In places like Florida, shellfish farms help clean harmful algal blooms, or red tides, from the water. While humans can’t eat the shellfish when a bloom is present, eventually the clam will filter the toxins from the water and through its body, becoming clean again to eat.

(What is a red tide—and how does it affect humans?)

Oysters and mussels are also just generally good for ocean health. Depending on how big and happy they are, they can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day, removing nitrogen from waters, ergo cleaning them as they eat, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Finfish aquaculture

Finfish is the most complicated of all aquaculture farming. From salmon to catfish to tilapia, farmers need to be able to control an environment as much as possible to raise healthy fish.

Most of these fish come from hatcheries: artificial breeding facilities where the fish are hatched and raised until they’re fingerlings (the size of a finger). They’re then transferred to a farm where they’ll continue to grow until harvested. Depending on what the fish needs to grow, the farm may raise them in warm or cold water and fresh or salt water—and either onshore, on the coast, or in the ocean.

Onshore, there are two main types of farms: earthen ponds and recirculating aquaculture systems.

Earthen ponds are natural ponds, which are equipped with paddles to help circulate the water, keeping it fresh and moving. In Alabama, Arkansas, and Mississippi, for example, these ponds can produce up to 10,000 pounds of catfish per acre, according to Anita Kelly, an aquaculture professor at Auburn University—although they’re vulnerable to threats from birds, snakes, turtles, and alligators that feast on these ready available fish.

Recirculating aquaculture systems are essentially industrial warehouses where sea water is pumped into filters that feed pools that house the fish. The wastewater is re-filtered, recycled, and reused within the tanks.

Coastal farms, meanwhile, mainly use floating net pens, which are the image most commonly associated with aquaculture; from above, these cages look like water-based crop circles.

Finally, an offshore farm is any farm that's established in strong and deep waters, Benetti says. These are the most labor-intensive forms of aquaculture—which is part of the reason why there’s only one in the United States, in Hawaii. They also require innovative processes to run: Farmers use spherical cages that look like floating metal orbs of netted fish. Although they can be moored or unmoored, they’re usually connected to a feed barge with a tube that pumps food to the fish.

The future of aquaculture

As aquaculture continues to expand, so do its innovations. In 2022, China, the leading producer of finfish aquaculture, launched the world’s first aquaculture ship. The ship has 15 tanks—each the size of two standard swimming pools—and is expected to produce about 3,700 tons of fish annually. Because the ship is mobile, the water for the fish is constantly exchanged with the sea, reducing the risk of disease and water pollution.

And environmentalists keep a close eye on the water quality surrounding net pens, where they say excess feed and condensed fish waste pose a danger of polluting nearby ecosystems.

To reduce that risk, some farms are looking to combine forces. In Norway, for example, one farm is growing salmon and kelp in the hopes that the kelp will absorb nitrogen and other nutrients expelled by the net pens to keep the waters clean.

As the aquaculture industry continues to grow at a rapid rate, experimentation is also ongoing. Environmentalists and farmers alike hope these new innovations and techniques will help feed our growing population, and perhaps even save our oceans.