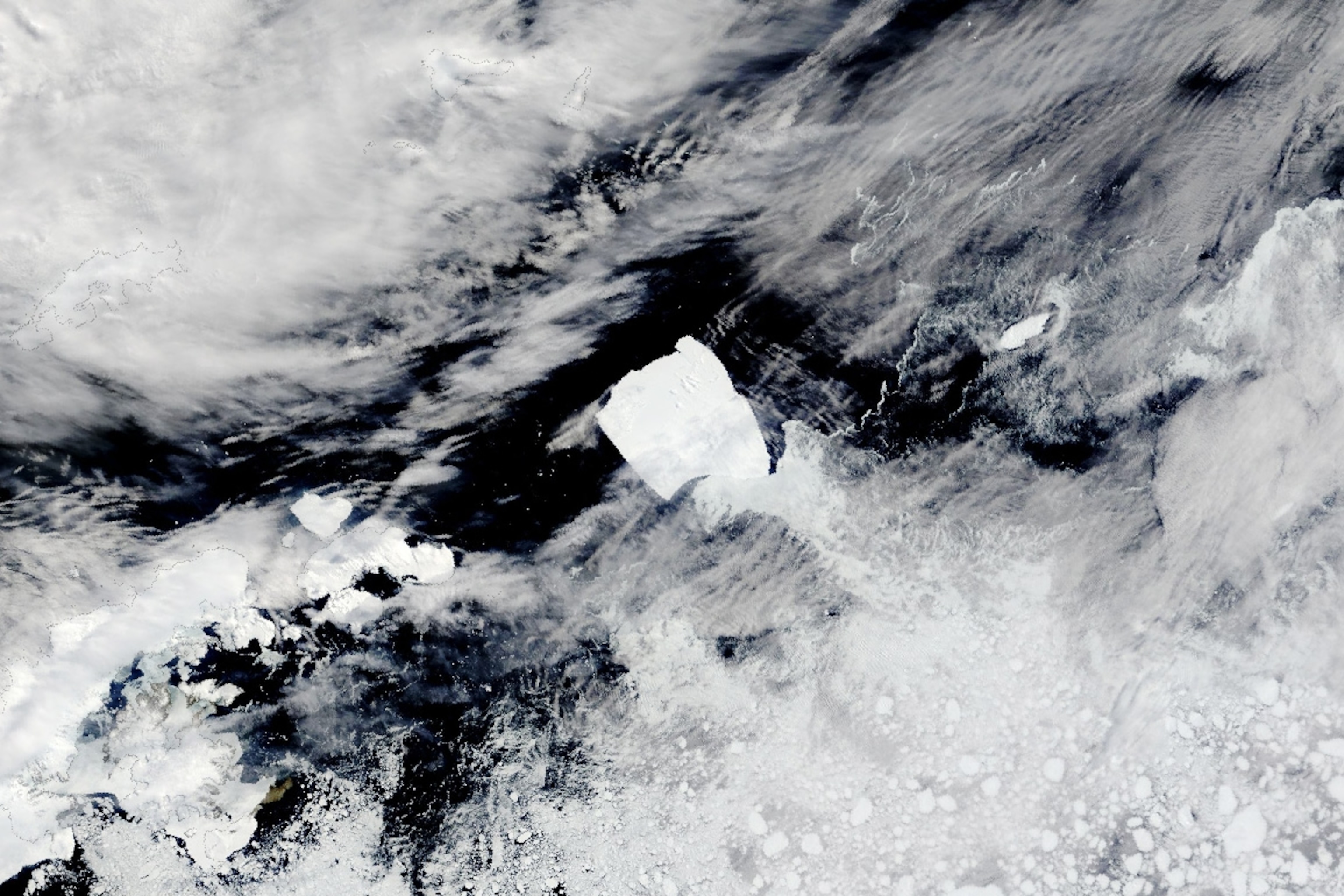

The world's largest iceberg is on a collision course with vital penguin sanctuary

This megaberg is the size of Rhode Island and weighs a trillion tons. It could ground to a halt near South Georgia, a critical wildlife haven.

An enormous iceberg known as A23a is heading towards South Georgia: a remote island in the southern Atlantic Ocean, filled with seals and penguins.

The trillion-ton megaberg was stuck in the ocean for nearly 40 years but, now it’s on the move. Although it’s creeping along at under 1.5 miles per hour, some experts are worried about its potential impact on this wildlife haven.

How did the iceberg break free, how might it affect penguin and seal populations, and is this related to climate change? Here’s everything you need to know.

Where did A23a come from?

In 1986, A23a—icebergs are named sequentially based on the Antarctic quadrant in which they were first seen—calved from the Filchner Ice Shelf. Iceberg calving is the natural process of icebergs breaking off from the ice shelf, which happens all the time.

A23a is notable for its size: “several tens of kilometers in length and a few hundred meters in depth,” says Martin Siegert, a polar scientist at the University of Exeter. “It's not uncommon, it's not unnatural, but it is unusual because it's just so big; very, very big.”

At just over 1,400 square miles, A23a could currently fill all of New York City, Los Angeles, and Houston combined. Because of its epic proportions, the behemoth “almost immediately got stuck” on the seabed around the continental shelf, which was too shallow for its keel to pass over, he says.

“It kept sitting there until about 2020” says Andrew Meijers, science leader of the British Antarctic Survey’s polar oceans program. As it lingered, the iceberg gradually melted and was buffeted by winds and ocean currents as chunks of ice tumbled into the water. Eventually, it freed itself into the deep ocean.

In April 2024, it became stuck again, circling in a Taylor Column— “an oceanographic phenomenon where rotating water above a seamount traps objects in place,” according to the British Antarctic Survey.

After breaking free in December, it’s now traveling along the Antarctic circumpolar current. “It's the strongest current on Earth,” says Meijers.

“It's going to head more or less straight towards [South Georgia],” says Meijers. This wildlife haven is home to fur seals, albatrosses, gentoo penguins, and more.

On its current trajectory, A23a will reach a sharp turn in the current. “The iceberg weighs a trillion tons so it's not turning on a dime,” he says. If it overshoots, it could run aground in shallow waters until it melts enough to keep moving or break up. “It’s anyone’s guess what it might do,” he says.

The threat to South Georgia's wildlife

Grounding near the shallow continental shelf close to South Georgia could block off routes between feeding and breeding areas for many penguin and seal colonies. This disruption “forces the adults to swim further, burn more energy and, basically, bring back less,” says Meijers, resulting in higher mortality and potentially worsening the impact of bird flu on both seals and penguins

Timing is important. “In October, the penguins decide where they're going to nest,” says Maria Vernet, a marine ecologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego. An enormous, steep iceberg that’s “more like an apartment building,” is a bigger threat when the eggs and chicks are in the nest and utterly dependent on their parents.

“But by February, all those chicks should be out of their nest” and can forage for themselves, she says.

There are other potential impacts.

In 2000, the B15 iceberg calved off the Ross Ice Shelf and acted “like a shield,” says Vernet, reducing the amount of light that could penetrate the ocean and reduced the growth of phytoplankton—which forms the base of the food web.

On the flip side, as the iceberg melts, it deposits iron that it picked up from grinding along the seabed, and stirs up deep waters, bringing rich nutrients to the surface. This encourages plankton blooms, “which attract krill, which then support pretty much everything in the Southern Ocean,” says Meijers.

“Drifting icebergs generate a little ecosystem with them,” says Vernet. If it brings the krill close to the rookeries, the penguins would have a feast.

An unpredictable outcome

“The ocean current is a series of complex, interconnected eddies,” says Siegert. “The average flow is in a certain direction, but it’s really complicated,” making it nearly impossible to predict where icebergs will drift.

Several icebergs have followed a similar path: in 2004, A38 grounded on South Georgia’s continental shelf with catastrophic wildlife impacts, A68 melted and missed South Georgia in 2020–2021, and, in 2023, A76 broke into smaller pieces in the waters around the island.

If A23a breaks up, it could be dangerous for ships navigating the treacherous Southern Ocean. “It’s the stormiest, most unpleasant ocean in the world,” says Siegert. It’s easy to track a slab of ice twice the size of London, but following a series of smaller icebergs is much harder. Plus, these can suddenly overturn.

Is climate change creating more giant icebergs?

This iceberg is “not something that is necessarily human-made, a climate problem—it’s not that,” says Siegert. “There's loads of icebergs calving all the time.”

But it helps to shine a spotlight on climate issues the region is struggling with. “Antarctica is experiencing mass loss to global warming and burning fossil fuels,” he says. Ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctic are losing ice six times more quickly than they were 30 years ago.

“There’s been an acceleration in the loss of the number of icebergs,” says Meijers. “Big ‘berg calvings are important, but a lot of it happens in much smaller chunks.”

It doesn’t take much to change these vulnerable ecosystems, and Siegert is concerned about the consequences of Antarctica’s ice loss. “This is a fragile environment,” he says.

Melting Antarctic ice sheets have a global ripple effect. The Southern Ocean helps to regulate the world’s climate by absorbing both heat and carbon, but warming waters make this harder. The melting also causes sea level rise. “There’s two meters of sea level rise locked in,” says Meijers. “There's nothing we can really do about that.”

For South Georgia, one thing’s certain. “It’s definitely going to shake things up,” says Vernet, “but it’s too early to tell whether it will be positive or negative for the ecosystem.”

Says Siegert: “from quite a cold, objective scientific perspective, it's actually quite an interesting phenomenon.”