See the Offices Where Employees Can Work in a Tree House

Online retailer Amazon's new building, the Spheres, highlights the value the tech industry places on exposure to nature and creative spaces.

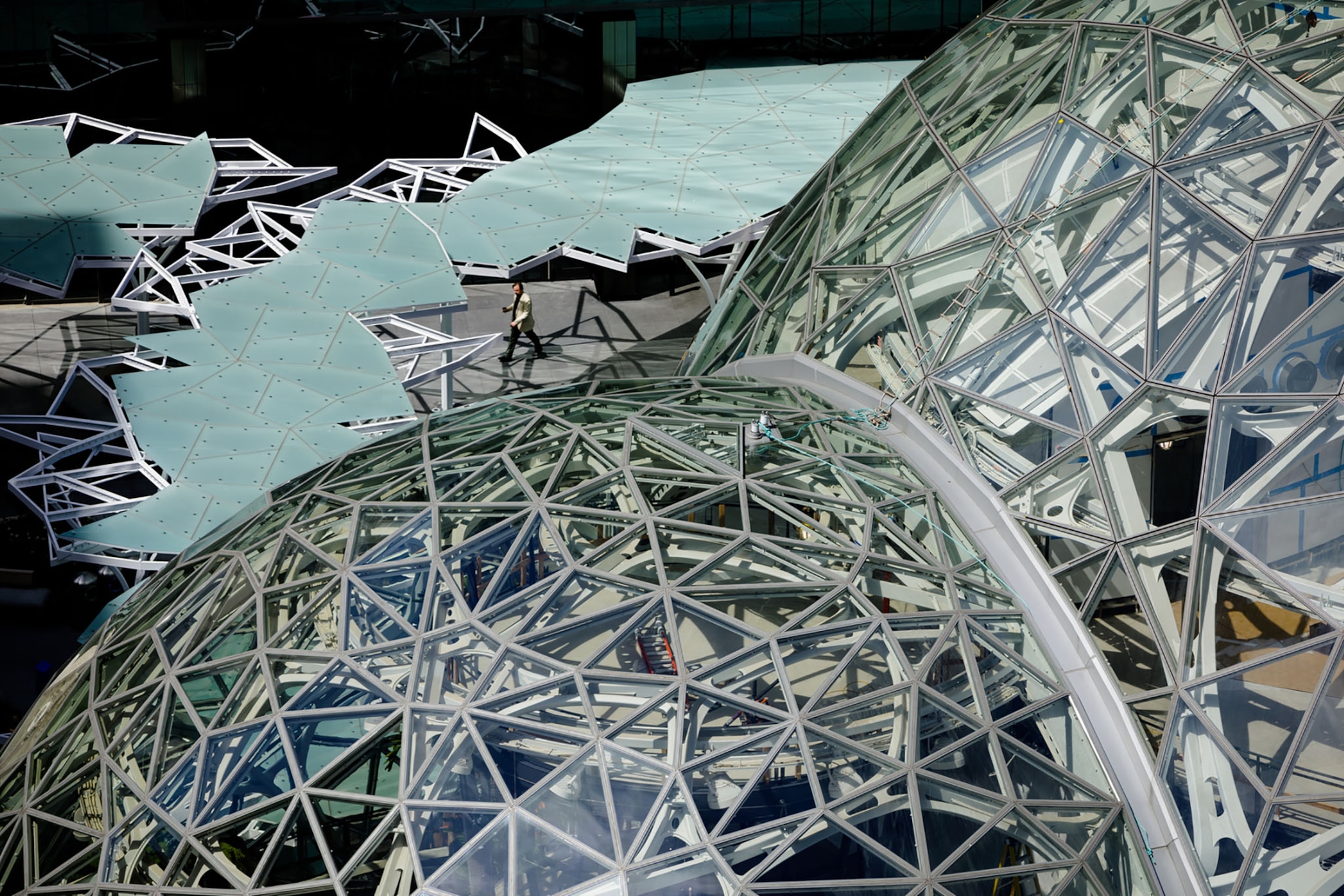

Seattle — The enormous orbs are constructed of glass pentagons held together with miles of steel and rebar but packed with lush tropical plant life, including epiphytes, rare begonias and a rhododendron normally only found at the top of a single mountain in the Philippines.

The Spheres, the new three-domed jungle of meeting and work space at the foot of Amazon’s headquarters in downtown Seattle, is both unlike any other office in the world—and yet similar to other spaces in the tech industry that showcase cutting-edge design.

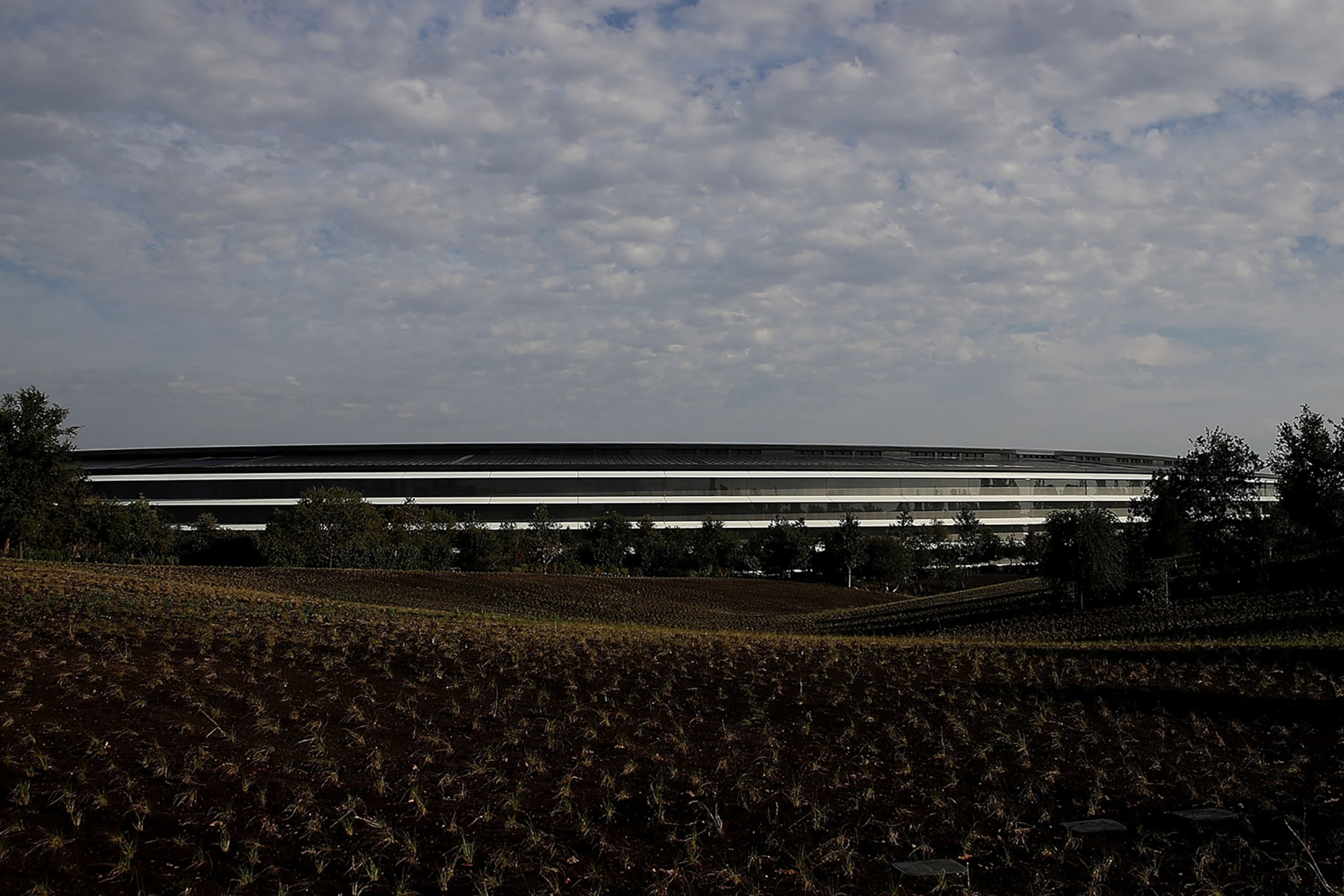

From Apple’s new circular spaceship campus in Cupertino, California, to Facebook’s Frank Gehry-designed headquarters with its nine-acre rooftop park complete with teepee swing, to the coming Googleplex with its glass tent-like buildings, these innovators have been stepping out of cyberland to rethink workplaces in the brick-and-mortar world. And each seems to have found value in trying to expose employees to more of the wild.

“Because we are an urban campus, one thing that is missing is a link to nature,” says Amazon's real estate chief, John Schoettler.

So the company brought nature to its employees.

Tree House Meetings

Amazon wants the Spheres to become as central to the city’s architectural identity as the 11-story, Rem Koolhaas-designed Seattle downtown library, the fluid, futuristic Museum of Pop Culture, built by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, and, of course, the Space Needle, the flying-saucer-on-stilts erected for the 1962 World's Fair that symbolizes the Seattle skyline.

Certainly, the project is an architectural marvel. The glass is designed to let in light for photosynthesis, but keep out summer heat. Interior lighting systems were inspired by the region’s newest growth industry—legal cannabis—and dangling digital monitors track how much light the plants are getting. Amazon’s campus sits across the street from a 34-story telecommunications data center that gives off enormous amounts of heat from computer and server hardware. Now they’ve tapped into it. Partnering with the owners of that building, Amazon pipes in waste energy, cycles it through heat-reclaiming chillers, and uses that to help heat its offices. The entire block, which includes Amazon’s 37-story headquarters, was recognized for sustainable practices with a green building certification, the company says. (See what makes a green building.)

From the outset, Amazon—set in a city surrounded by water, mountains, and dark gothic Douglas fir forests—wanted the Spheres to focus on flora.

“We liked a lot of the elements of the old Victorian conservatories,” Schoettler says. “We thought, What would Kew Gardens look like if it were being built today?”

Just inside the main entrance to the Spheres, which celebrates its grand opening this week, Amazon visitors face the largest of its living walls of flora, a breathtaking four-story vertical maze of 25,000 plants. The wall includes several hundred species, from cliff-dwelling orchids to understory ferns. They spring from mesh, with cooler-weather species along the bottom and sun-loving plants near the upper reaches, just below the 90-foot top of the glass dome.

A few feet away, workers pass a rainforest paludarium, an enclosed glass display of plants and freshwater fish typically found on the flooded forest floors of one particular watershed in the Amazon. Elsewhere, a similar vivarium includes plant life from Borneo shrouded in cloud-forest mist, while wall-mounted terrariums around the building will rotate special plant collections. Above towers a nearly 60-foot rusty fig, trucked in 1,200-miles from California. Equatorial trees and plants abound, from a pink lantern plant to a cocoa tree to a fern expected to eventually stretch fifteen feet across a walkway. Another living wall boasts a slew of carnivorous foliage, including insect-nabbing pitcher plants.

This place is not a museum or conference center, nor will it be open to the public. It’s an extension of Amazon’s workspace, another hiring lure in the ultra-competitive tech world. In fact, it can only hold roughly 800 of the city’s 40,000 Amazon employees at a time, and officials say they already have a waiting list of workers who want to use this space.

But the Spheres is also a means to encourage creativity and invention, says Ron Gagliardo, Amazon’s lead horticulturalist on the project. There are no cubicles or offices, only open gathering spaces that include waterfalls or a cocoon of creeping vines. Another meeting spot is a wooden tree house high above the canopy. It smells like a lush and fragrant forest, feels like a greenhouse kept cool for visitors, and looks like an elaborate futuristic pea patch planted aboard a gleaming space shuttle.

“It’s a place to meet a colleague, bring a recruit, hold a team meeting,” Gagliardo says. “It’s a place to come and think a little differently.”

Nature ‘Is Not Optional’

This embrace of biophilia—the idea that humans have an innate desire to connect with nature—should not come as much of a surprise. Experts increasingly suggest that access to nature can improve brain function and creativity, and increase problem-solving. And few industries seek a creative edge as competitively as tech.

Timothy Beatley, a professor of sustainable communities at the University of Virginia’s School of Architecture and a specialist in biophilic urban planning, says some industries are beginning to figure out that humans need nature—“it's not optional.”

“Nature is something we absolutely need to lead happy, healthy, meaningful lives,” Beatley says. “We need to overcome this sense that you should just get out in nature once or twice a year on a holiday.” (Read about Singapore, the "garden city.")

Research increasingly shows, Beatley says, that there may even be links between nature—ranging from plants and real sunlight, to natural ventilation and simply being outside—and improved physical and mental health. (Read “This Is Your Brain on Nature.”)

“Medical people are cautious—they don't see causality, but there is a lot of correlation between nature and health,” Beatley says. “It calms us, lowers blood pressure, we perform better on cognitive tests, think more clearly, we’re more likely to be generous, to be more cooperative, to think more long term. And there’s a lot of emerging evidence about increases in worker productivity.”

The latter was not lost on Amazon, and the company is hardly alone. Google’s new campus plans include tent-like coverings that help bring in natural light, supporting “trees, landscaping, cafes, and bike paths weaving through these structures” it hopes will “blur the distinction between our buildings and nature.” Apple moved parking underground to create tree-rich paths for “walking meetings.” Facebook’s roof boasts a small trail system.

But that’s not to say that Amazon designers hit the books to design a building with specific health outcomes in mind. Officials say they weren’t thinking quite so proscriptively.

“To be perfectly honest we didn’t do a tremendous amount of research,” Schoettler says. “We just wanted the link to nature that was missing in the traditional work environment.”

And, says Beatley, sometimes that’s enough.

“Exactly how much you need is still a hard thing to say,” Beatley says. “But there’s no doubt that the more we can do the better.”