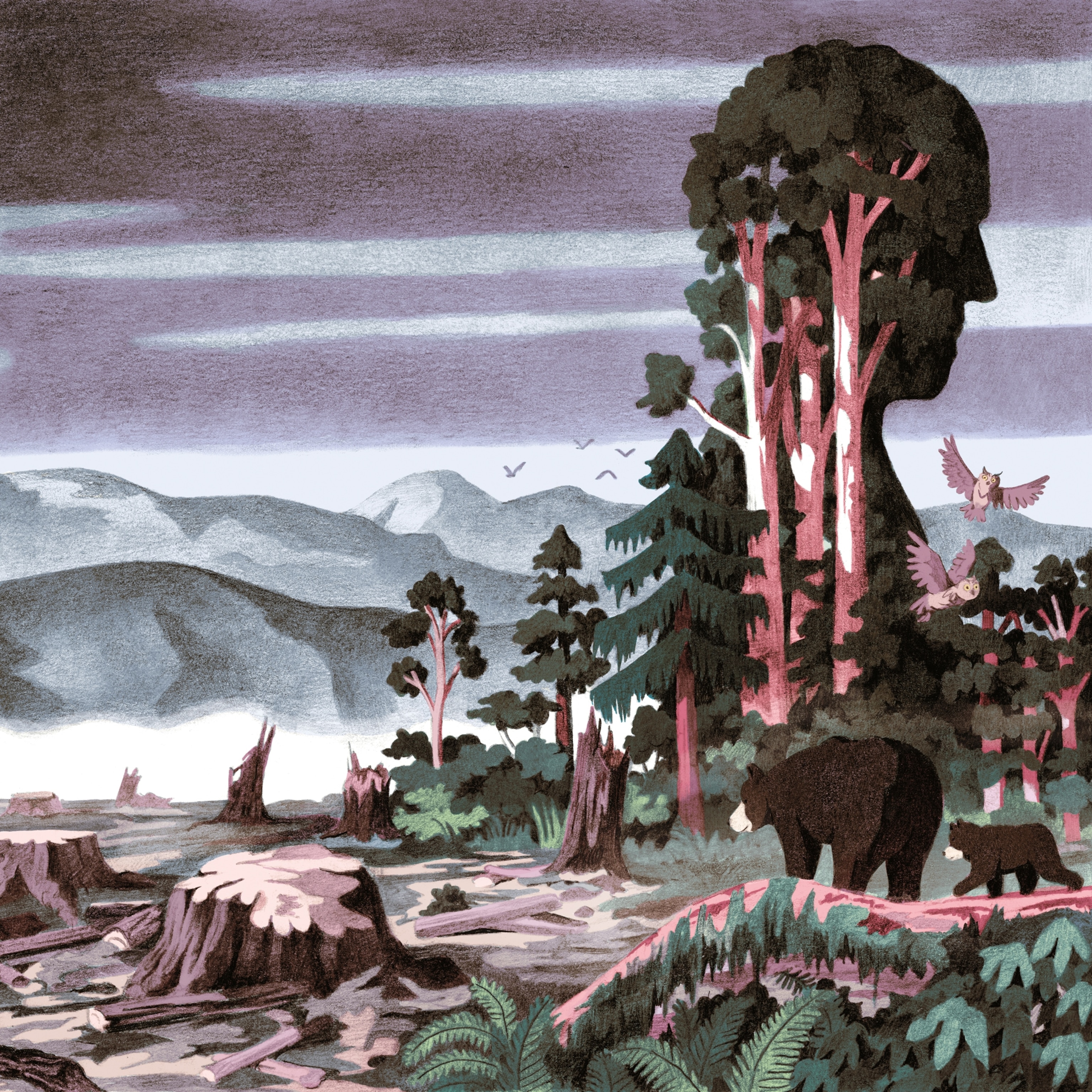

To keep the planet flourishing, 30% of Earth needs protection by 2030

The move would safeguard biodiversity, slow extinctions, and help maintain a steady climate, a leading group of conservationists say.

This week a United Nations working group responded to a joint statement posted online in December by some of the world’s largest conservation organizations calling for 30 percent of the planet to be managed for nature by 2030—and for half the planet to be protected by 2050. But exactly what counts as “protected”—and how countries can reach those goals—is still up for debate. (direct download)

Conservationists say these high levels of protection are necessary to safeguard benefits that humans derive from nature—such as the filtration of drinking water and storage of carbon that would otherwise increase global warming. The areas are also needed to prevent massive loss of species.

Humans and their domestic animals are squeezing the rest of life on Earth to the margins. Today, only four percent of the world’s mammals, by weight, are wild. The other 96 percent are our livestock and ourselves. Since 1970, populations of wild mammals, birds, fish, and amphibians have, on average, declined by 60 percent.

Habitat loss is widely regarded as the top cause of species extinction around the world and these dramatic population declines are a red flag that many species are on thin ice—but the good news is that there is still time to save most species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species lists 872 species as extinct, but a whopping 26,500 species as threatened with extinction. To save those species, their homes and the other species with which they depend must be protected—and quickly.

“We’ve got a really tight clock,” says Brian O’Donnell, director of the Wyss Campaign for Nature, based in Durango, CO, who advocates globally for more conservation areas. “Every year we wait, we put more species in peril.”

The call is part of a process of setting global environmental targets organized by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Negotiations on the specifics of the target will continue until a meeting in Beijing in October 2020.

The targets will replace and go beyond the “Aichi Biodiversity Targets,” which were set in 2011 and are supposed to be reached by 2020. Among them is a goal of protecting 17 percent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas.

Those goals are still within reach. As of 2018, 14.9 percent of the Earth’s land surface and 7.3 percent of the world’s oceans are formally protected.

Signatories of the 30 percent by 2030 call posted this week include BirdLife International, Conservation International, the National Geographic Society, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Nature Conservancy, and nine other non-governmental organizations. Most see the 2030 target as a stepping stone on the way to an even more ambitious goal: conserving half of the planet by 2050.

Calls to protect half the Earth date back to the 1970s, but the concept has gained momentum in recent years thanks to the 2009 founding of the Nature Needs Half movement and the 2016 publication of eminent naturalist E.O. Wilson’s book Half Earth..

“There has been a great convergence of thought in terms of people thinking on a bigger scale,” says Jonathan Baillie, executive vice president and chief scientist at the National Geographic Society, based in Washington D.C. “It is very rare to get all the major conservation organizations to agree to one thing.”

Supporters say that having an ambitious and clear target may help the crisis of biodiversity loss get the attention it deserves from governments and private institutions. In recent years, concern over climate change has captured more attention.

O’Donnell says that at the latest meeting on the Convention on Biodiversity country’s environment ministers were the highest ranking officials attending, and many of those only stayed for part of the meeting. In contrast, meetings of the Paris Climate Accord are attended by presidents and prime ministers. At the same time, the climate talks receive far more media and public attention. But the issue of saving biodiversity “needs to be elevated among global leaders,” O’Donnell says.

Including indigenous people

Some observers are waiting to hear more details before they support the idea.

The call to protect 30 percent of the Earth “alarmed” Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, based in Baguio City, Philippines. Tauli-Corpuz was one of the authors of a 2018 report criticizing conservation organizations for kicking indigenous people off their traditional lands to create protected areas, preventing those previously displaced by parks from reclaiming their lands, or aggressively policing their behavior and harming their livelihoods by prohibiting farming or hunting.

Conservationists increasingly acknowledge the rights of indigenous people to their lands, and even point to the fact that land controlled by indigenous people is often much better cared for, from a biodiversity perspective, than land controlled by settlers. Although indigenous people make up less than five percent of the global population, they own or manage about 25 percent of the Earth’s land—much of it far more diverse and sustainably managed than the remaining three quarters. And despite the challenges of poverty and insecure land rights, indigenous people and local communities spend around four billion dollars a year on conservation—a significant chunk of the total global spend of about 21 billion.

But Tauli-Corpuz, who is indigenous herself, says ideologies change slowly, and for many the full-time presence of people making a living seems incompatible with conservation. “I think they are still trapped in the idea that people should not be intervening in nature,” she says. “I came from a meeting in Nairobi a few days ago, and almost all the speakers were still speaking about this issue.”

She has called for a grievance mechanism to be set up, so that indigenous people can formally complain to the United Nations if they are harmed by conservation projects, but this has not yet been done. Restitution of land and resources taken by earlier conservation projects has by and large not happened yet either, she adds. “Calling for an increase without dealing with the issues raised by indigenous people is going to be problematic,” she says.

Those behind the 2030 call say that land managed and inhabited by indigenous people and other local communities will count toward the target. “Protecting biodiversity means protecting indigenous rights,” says O’Donnell. “That is going to be at the center of 30 percent for the planet, rather than in conflict with it.”

Innovative new approaches

Some areas are managed by local people for both conservation and sustainable use. O’Donnell and Baillie both gave the example of the Northern Rangelands Trust, a consortium of conservancies in Kenya in which local pastoralists from 18 different ethnic groups manage their land for both livestock grazing and wild animal conservation, with the financial and logistical support of NGOs and governmental institutions.

The project makes clear that not all of the “protected areas” in the 30 percent target will look like the kind of parks and reserves many Americans are familiar with. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature has created a typology of categories of protected areas, ranging from Type Ia, “Strict Nature Reserves,” with limited access for people, to Type IV, “Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources”—which more or less describes many places where indigenous people live today.

This, coupled with the superior track record of indigenous people in protecting biodiversity, is why Erle Ellis, an environmental scientist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County says that as far as he is concerned, “enforcement of indigenous sovereignty should be automatically part of that 30 percent.”

Beyond the many flavors of “protected area,” the call includes room for “Other Effective Area Based Conservation Measures.” As the capitalization hints, this is not just a vague phrase, but an increasingly codified category of land management, first sketched out in the 2011 Aichi targets. One report defines it as “a geographically defined space, not recognized as a protected area, which is governed and managed over the long-term in ways that deliver the effective in-situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem services and cultural and spiritual values.”

Potential examples include traditional hunting and gathering grounds; natural areas on military bases; areas set aside for scientific research; sacred sites and cemeteries; pastures of native grasslands; or even diverse city parks.

Avoiding “paper parks”

According to the groups’ vision statement, the 30 percent that is protected won’t just be the part that is cheapest and easiest to protect, but should be fully representative of the diversity of the planet’s ecosystems. Yet that may be difficult to achieve by 2030, says Ellis.

“The big question about getting to 30 percent in a little over ten years is whether the speed is going to sacrifice quality,” he says. “It would be a shame if people tried to get there fast by conserving the land that isn’t really under pressure.”

Likewise, he says, conserving land without making sure there is long-term funding to manage it and plans to ensure the stability and prosperity of surrounding communities risks creating “paper parks” that are routinely plundered of resources by those who don’t have a stake in the area or are driven by necessity. “By trying to move too past it is possible that they will create a huge realm of failed conservation,” he warns.

So the emerging vision is more complex than the “30 percent by 2030” slogan may suggest. By 2030, leading conservationists say, Earth should dedicate 30 percent of its land and sea to a robustly financed, locally supported, ecologically representative mix of areas managed for the benefit of nature.