Why old-growth forests matter

Ancient forests could get protection in the U.S. under a new directive aimed at helping these remarkable trees survive multiple threats.

One of southern California’s oldest giant sequoias holds more leaves than there are people in China. It has stood since there were fewer people on Earth than live in modern Japan—more than 3,000 years. It was a seedling hundreds of years before Aristotle began tutoring Alexander the Great—and it is still living today.

In the Hoh Rainforest on Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula, towering above mushrooms and damp ferns, are green, moss-draped spruces and hemlocks that were alive in the late 1500s “when Sir Francis Bacon and Johannes Kepler first recognized the value of objective data over mystical portents,” scientist Jerry Franklin and his co-author, Ruth Kirk, wrote in The Olympic Rain Forest: An Ecological Web. Those trees “have been pushing their roots through the soil and wafting seeds into the air throughout the entire existence of science."

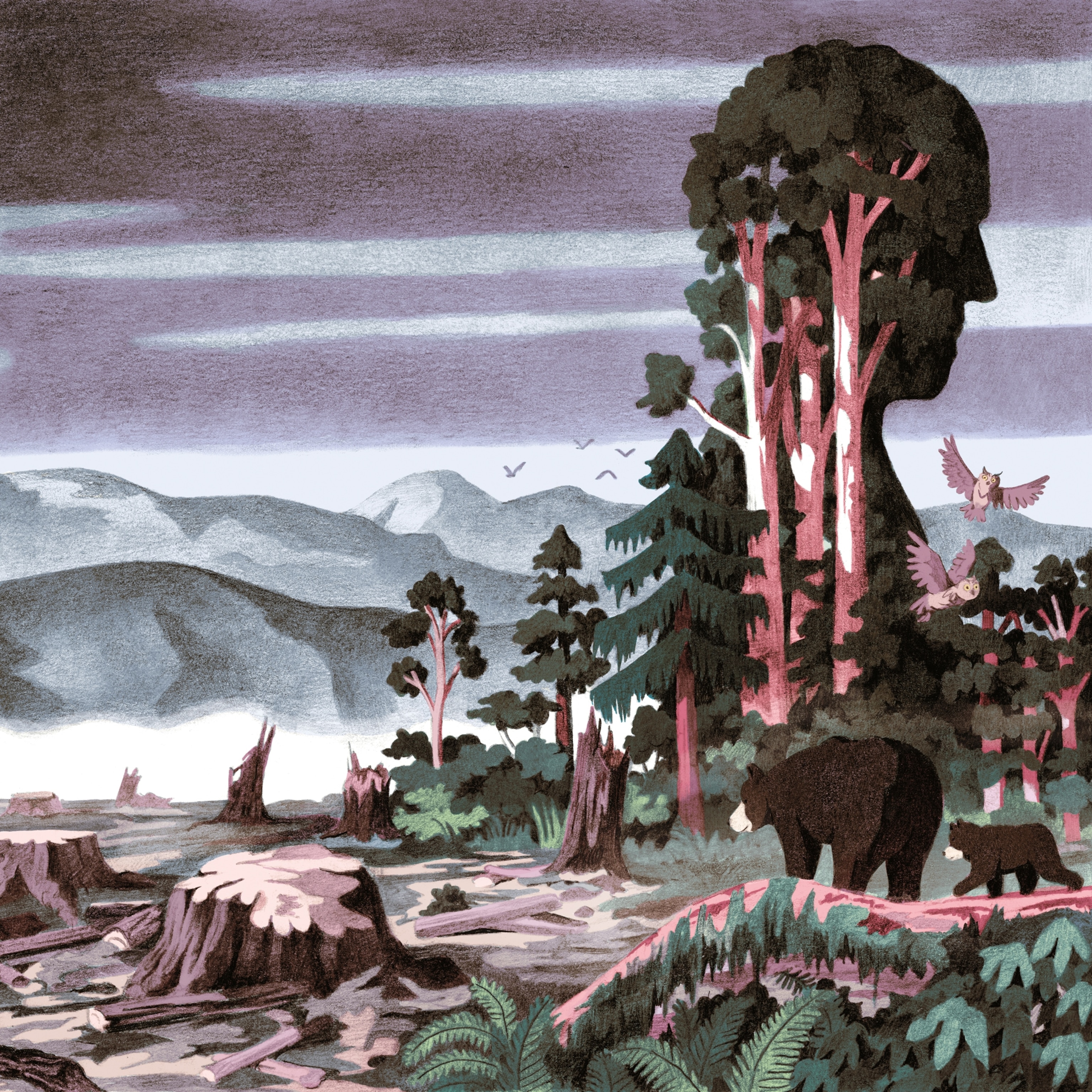

These are examples of old-growth forests—one wet, one dry—both full of ancient trees with webs of roots surrounded by a complex array of life above and below ground. Far more than just linking us to our past, the world’s mature and old-growth forests perform amazing ecological feats, even as they face all new threats. They support a greater diversity of life, hold cleaner water, and host surprisingly complicated communication networks made of fungi that relay messages between trees underground—even trees of different species.

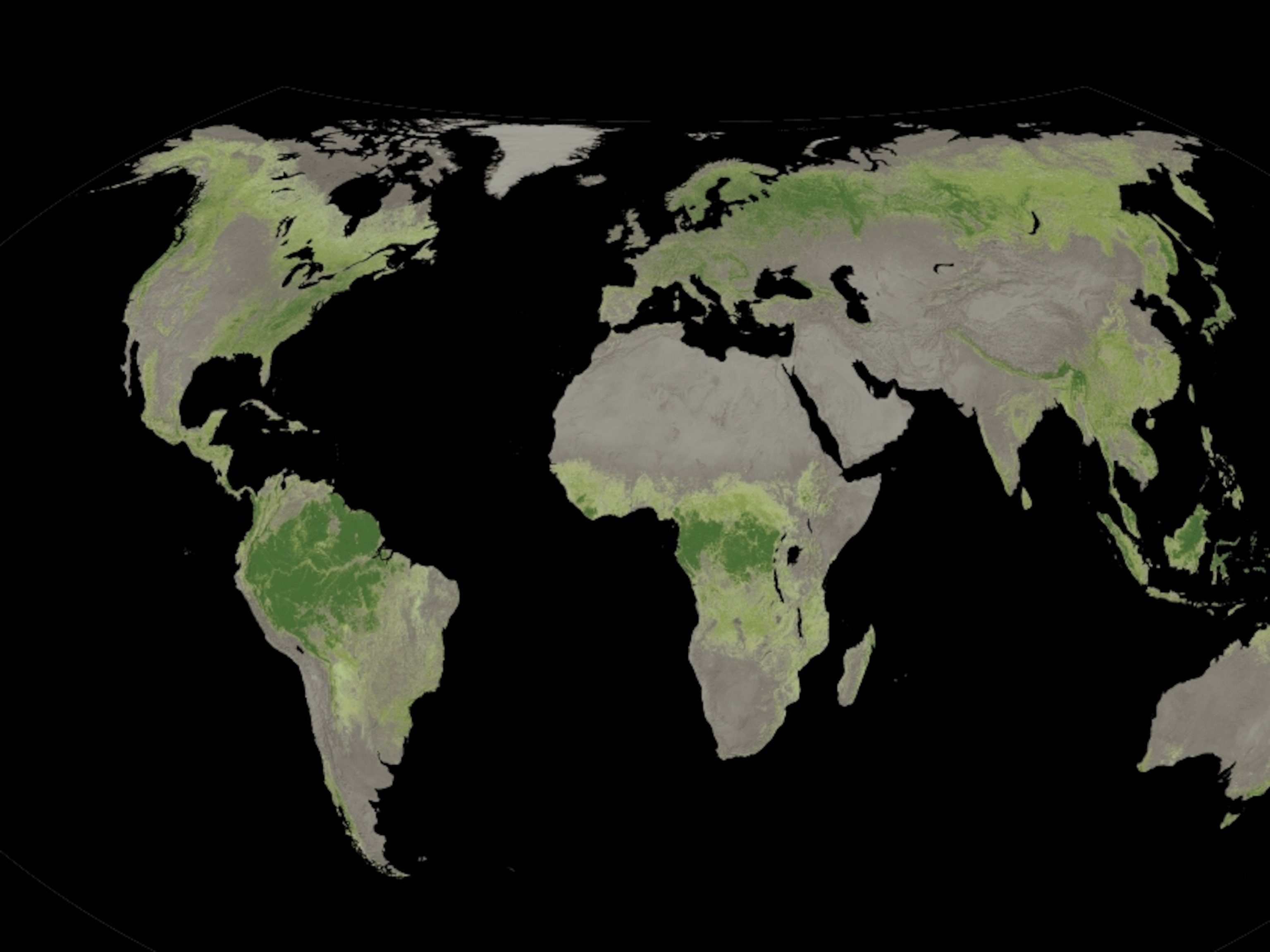

They hold far more carbon than younger forests, helping to protect us from our own fossil-fuel emissions. A study of six national forests in Oregon showed the biggest 3 percent of trees accounted for 42 percent of forest carbon.

Where carbon storage is high, plant and animal diversity tends to be richer than anyplace else. In the Hoh, for example, when researchers climb to the tops of trees, they sometimes find baby trees sprouting from soil on the branches. “The forest canopy has its own ecosystem—there are huge varieties of mosses and lichens and insects and birds,” says old-growth forest expert Beverly Law, at Oregon State University. “It’s just a different world up there.”

A first step to protect old-growth forests

These days, climate change poses greater threats than ever to mature and old-growth forests, bringing higher risk from wildfire, drought, excessive heat, more powerful storms, and pest invasions. But in countries across the globe from Indonesia to Brazil—and even in the United States, especially Alaska—old-growth forests are still being logged.

On April 22, 2022, to mark Earth Day, President Joe Biden came to Seward Park, a city park in Seattle that’s home to some remnants of old-growth forest, to sign an executive order mandating the first inventory of the nation’s mature and old-growth forests. The order requires federal scientists to detail the specific threats posed to each forest.

“All around this country there used to be a hell of a lot more forests like this,” Biden told the small crowd.

A host of prominent experts, including 135 forest scientists, had been urging Biden to protect old-growth forests since he became president, explaining in a letter two days before he signed the order that “older forests provide cool, shaded forest interiors for sensitive species and those needing time to migrate and adapt to changing environments. Large trees create vital habitat structure and complexity for imperiled fish, other aquatic life, and terrestrial species."

The scientists noted that old-growth forests “store and gradually release clean drinking water for millions of Americans while mitigating flood and fire impacts resulting from climate-driven increases in erratic and severe weather events. Finally, such forests and legacy trees attract visitors and inspire awe, supporting recreation and rural economies.”

There is no single definition for old-growth forests, because that depends on the ecosystem. Bristlecone pines can live 5,000 years. Some other tree species may only live 150 years, but if they are in forests largely undisturbed by humans, researchers may still consider them old-growth. What these forests have in common is an ever-changing complexity that promotes symbioses among species.

There are mosses and broken, leaning snags of branches; cracked trunks; broken treetops; multiple varieties of trees; downed “nurse logs” that host new growth as they decay; and tree canopies of varying sizes and shapes. All of those differences over time have created pockets for a wide variety of life.

“There’s just a huge diversity of animals and plants, huge soil diversity,” in old-growth forests, Law says. “And biodiversity—genetic biodiversity, species biodiversity—is necessary for resilience. It’s what protects forests from diseases and everything else. It’s essential for life to continue.”

Guru of old growth

One could argue that our understanding so far of old-growth forests really started with Franklin, a University of Washington scientist often considered the “guru of old growth.” In the 1970s and 1980s he started doing research in the Douglas fir canopies of the Pacific Northwest. He was among the first to urge loggers to leave behind woody debris and dead snags of branches, the complex structure that helps old forests sustain life.

In the 1980s, decades of clearcutting threatened to extinguish spotted owls, a shy and charismatic coffee-colored species that had come to symbolize the complex value of forests across Washington, Oregon, and northern California.

By the early 1990s, the battle between loggers and environmentalists reached a fever pitch, and the Clinton administration turned to Franklin to help find a new way to manage forests. The Northwest Forest Plan, adopted in 1994, put a stop to timber cutting on 80 percent of 24 million acres overseen by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management.

In places like Canada’s British Columbia or Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, however, old-growth forests still get chopped down for lumber, but also for cardboard boxes and chopsticks. “That,” Law says, “is unconscionable.”

As Franklin wrote more than 30 years ago, what makes old-growth most important is that it’s irreplaceable.

A sequoia seedling blooming today won’t be as mature as southern California’s oldest giants until the year 5,000.