Beloved yet banned: The surprising history of tie-dye

The ancient art form has existed for thousands of years. In that time it’s been outlawed, used in religious ceremonies, and celebrated as a symbol of love.

Tie-dyed clothing might not seem like millennia-old artistic craft. Known in North America as a symbol of the 1960s hippie movement, it makes for an easy DIY project with materials available at the dollar store.

But throughout history, tie-dying has been a coveted, bespoke—and in some cases, forbidden—practice that could convey an individual’s status, role, and beliefs.

Different methods and styles of tie-dye originated largely independent from each other across the ancient world from Peru to Nigeria, Japan and Southeast Asia. The technique is a form of resist dyeing, in which thread is used or the textile is tied onto itself, to create knots that protect certain areas of the material from being dyed. Each culture found unique twists to add through their designs, including dyeing cloth tied to sticks, drawing patterns in wax, or making knots with rice, rocks, or seeds.

It’s impossible to say which culture developed tie-dyeing first, and when. Often delicate and made of organic fibers, textiles are especially susceptible to deterioration, so experts believe the earliest examples in all cultures have been lost to time.

Lee Talbot, curator at the George Washington University Museum and the Textile Museum, says that’s evidenced by the “perfection” in earliest surviving samples we’ve found—“We're not seeing a long period of experimentation… they've been doing it for a really long time.”

Experts on historic textiles share the cultural meanings behind different tie-dyeing methods around the world, and how they’re living on today.

Bandhani: India

Bandhani is the oldest known form of tie-dye, dating back to 4,000 B.C. in Indus Valley Civilization, which was based in the northern region of modern day India. It’s still produced around the subcontinent today.

Bandhani patterns are created by plucking the cloth into tiny peaks and binding it with thread before applying dye. A series of these small knots, which allowed fabric underneath to be untouched by dye, form whirls and patterns on clothes such as sarees, scarves, and turbans.

Patterns on modern bandannas used in the West evolved from bandhani, according to Natalie Nudell, adjunct assistant professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology.

Some of the oldest depictions of bandhani were preserved in written records and paintings in the Ajanta caves in Central India. In Northern India, the textiles were mentioned in songs and poetry as symbols of love and affection.

Talbot says this association between bandhani and love remains a fixture in India today—bandhani is often worn and given as gifts at weddings.

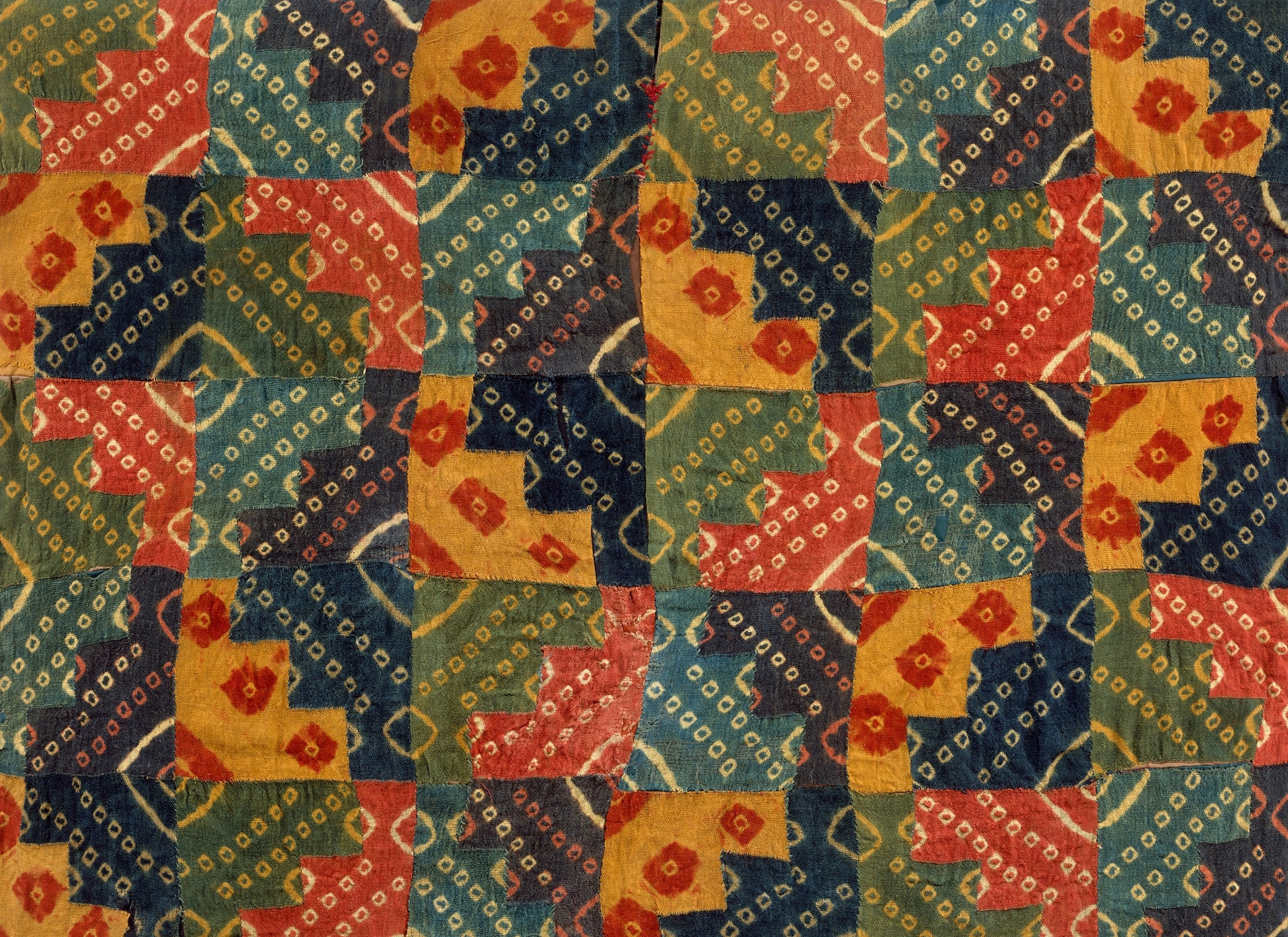

Amarra: Peru

Amarra emerged around 1,500 years ago in Peru. The tie-dye practice spread across the Americas—as far as the southwestern United States, where some of the earliest amarra textiles created by ancestral Pueblo peoples were discovered dating back to the tenth century.

A distinct feature of amarra is the gridded design of diamonds with dots in the center, a pattern symbolizing snakeskin or fields of corn, according to Laurie Webster, a visiting scholar with the University of Arizona.

Webster says these were sacred motifs to Indigenous groups in the Americas, who used tie-dye to make the design on clothing, blankets, and other decorative textiles.

In murals and other visual records that remain, Webster says deities and religious figures are often depicted wearing amarra.

Shibori: East Asia

Although shibori dyeing techniques originated in China, they are best known as a Japanese art form that emerged more than 1,000 years ago. The first surviving samples of shibori in China date back to the fourth century. This is still practiced in the country today, particularly by ethnic minorities in southwest China.

You May Also Like

For one method of shibori, craftspeople place a grain of rice or a small piece of metal for each knot of cloth and bind it tightly in thread. After the textile is dyed, the threads are released, creating small circles. It takes many hours to complete the process of tying, dyeing, and untying the fabric to create intricate patterns.

“It's an extremely time consuming, laborious technique that is highly revered [in Japan],” says Nudell.

Peasants used indigo to make shibori designs on hemp clothing, according to Talbot. Shibori kimonos made of silk were expensive to purchase and were largely worn only by the upper class.

Shibori was popular with nobles, wealthy townspeople, and even high-ranking courtesans. When they became a symbol of extravagance, the ruling shogunate banned it altogether as part of Japan’s sumptuary laws.

These laws decreed how each social class could dress and spend their money. The ruling Tokugawa shogunate portrayed these as moral responsibilities to uphold the hierarchy. This particular edict, passed in the late 1600s, said no one could make shibori.

The designs remained popular even during the ban—prompting artists to mimic shibori designs with stenciling. The ban on shibori was lifted in 1868, and it remains a popular traditional practice for kimonos in Japan.

Adire: Nigeria

In Nigeria, the Yoruba people made adire by pleating cloth before tying it with thread or banana leaf fiber and dyeing the fabric. Like shibori, the textiles were often dyed blue with indigo.

They also created circular patterns by wrapping stones and large seeds within the textiles, also similar to shibori.

For the Yoruba people, Nudell says that adire designs on clothing were closely tied to an individual’s identity. Adire often carried symbols of the wearer’s social and cultural status—such as their age or rank in society.

“Each culture interprets [tie-dyeing] in a slightly different way, and they interpret it into their own aesthetic,” says Talbot.

Adire still holds a significant social and economic role for people in Nigeria, as creating clothes, bedding, and decorations provides job opportunities for local farmers, weavers and dyers.

Throughout centuries and across the globe, Talbot says there is something about tie-dye that catches cultural attention.

“Whereas a lot of hand techniques have fallen out of use or fallen out of fashion, tie-dye is something that seems to be perennially popular,” says Talbot.