Haunting images revisit the railways that united Bengal—until India's Partition divided it

On the 75th anniversary of the end of colonial rule, photos document the British Empire's lasting imprint on the part of India that is now Bangladesh.

Born four decades after the 1947 Partition of India into what eventually became three nations, Bangladeshi photographer Sarker Protick, 36, has been documenting the fragments of "united" British India—homes, inheritance, transport—that remain in today's Bangladesh. His canvas in this project is the rail system that left the British Empire's lasting mark on the part of India that was first known as East Bengal, before becoming East Pakistan in 1947, and finally Bangladesh in 1971.

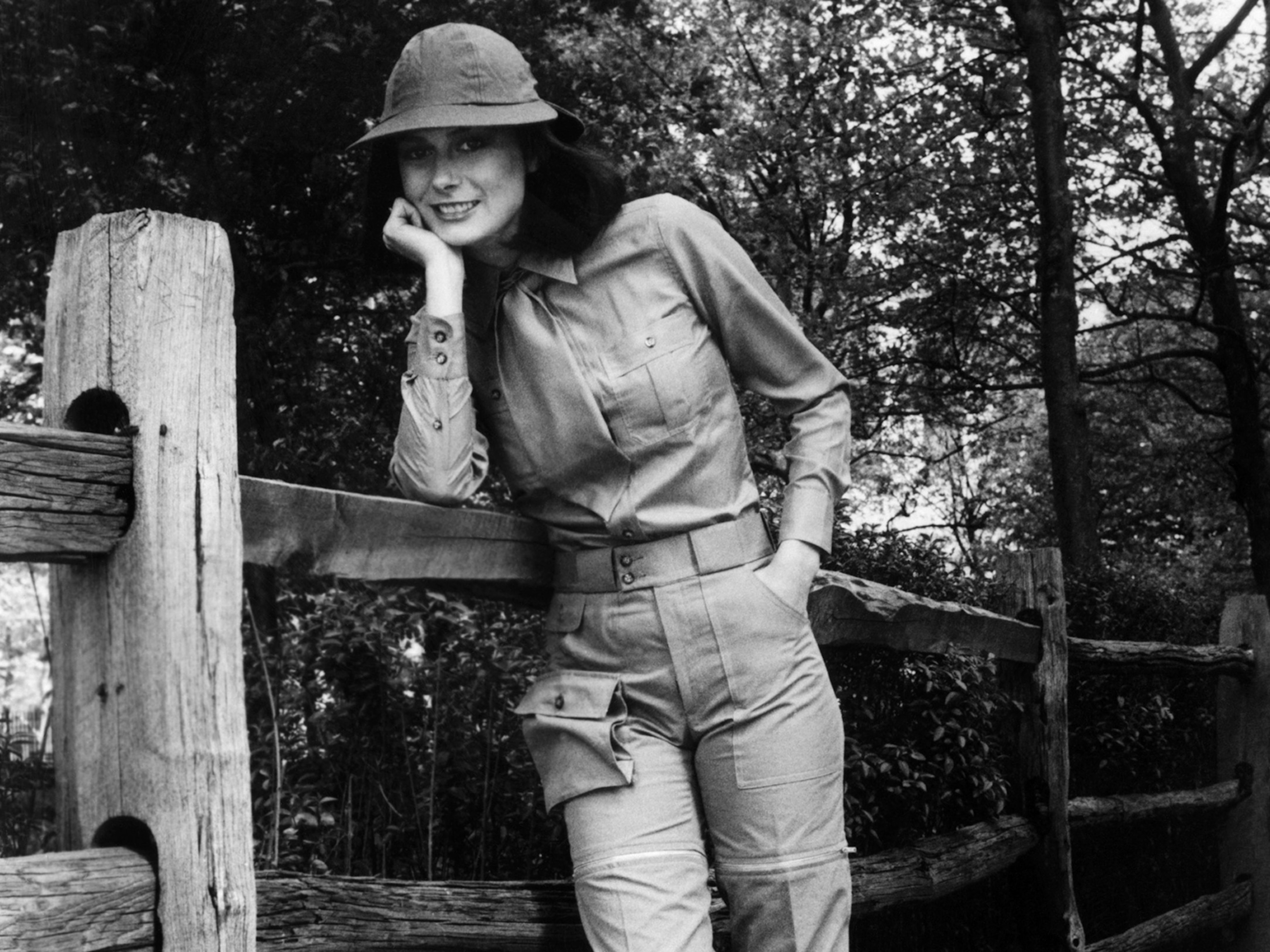

Protick’s photographs have emptied the space of people; what we see instead are skeletal train tracks and the traces of commerce, habitation, manufacturing, and entertainment that grew up around this architecture of connectivity. There are occasional human figures—a nurse, an entertainer, a mystic—but those people carry an air of confusion, almost as if the activity that surrounded these train depots for a century has vanished, and they forgot to catch the last train leaving the station.

Bangladesh has a complex position within the narratives of India’s 1947 Partition, as it was, from one perspective, left behind. British mapmakers split Bengal, a northeastern corner of India that had a shared language and culture, along religious lines. It was splintered into Muslim-majority East Pakistan, which decades later became Bangladesh, and West Bengal, an Indian state to which millions of Hindus fled after the new lines were announced. Today's Bangladesh features in partition stories as a bucolic "before times" that was lost and abandoned.

That idea of being left behind in 1947 is the portal through which I enter Protick's images of the East Bengal Railway, now the national railway of Bangladesh. East Bengal was the fertile, lush agricultural heartland of India—but its connectivity to the British administrative capital of Calcutta (now Kolkata), and to the rest of British India, was hampered by the densely riverine landscape.

The first railway system in the world was set up in 1825 in England; within 40 years the British had set up a private company called Eastern Bengal Railway to corral the remote parts of eastern India–its people and resources–under British imperial oversight, using rail lines. While the railway system led to hyper-development of imperial capitalism, it also enabled human connections, a rising middle class and business community, and a newly empowered polity that allowed the flourishing of all-India political alliances. These pan-India movements became national forces behind the "Quit India" independence movement that finally expelled the British in 1947, when they were exhausted by World War II.

Thus railroads that led to a zenith of British colonial expansion also laid the tracks for its eventual annihilation.

Within a plethora of crossings and junctions, what is salient is that many of these rail lines started in one country and ended in a different one after 1947. Trains across Bengal were the conduit for refugees fleeing into and out of India. Passenger flows continued for two decades after independence, but the lines of control hardened after the 1965 India-Pakistan war. Today what remains is the Bangladesh Railway, a decrepit and moribund institution plagued by the woes that fuel third world disenchantment: decolonization followed by homegrown corruption and the incompetence of state management.

The railway is still the chosen mode of transport for a vast working-class population, but an ever-expanding highway and bridge system now provides faster alternatives for people and goods. Protick’s vacant, haunted photographic tableaux evoke the feeling of what was left behind by decolonization.

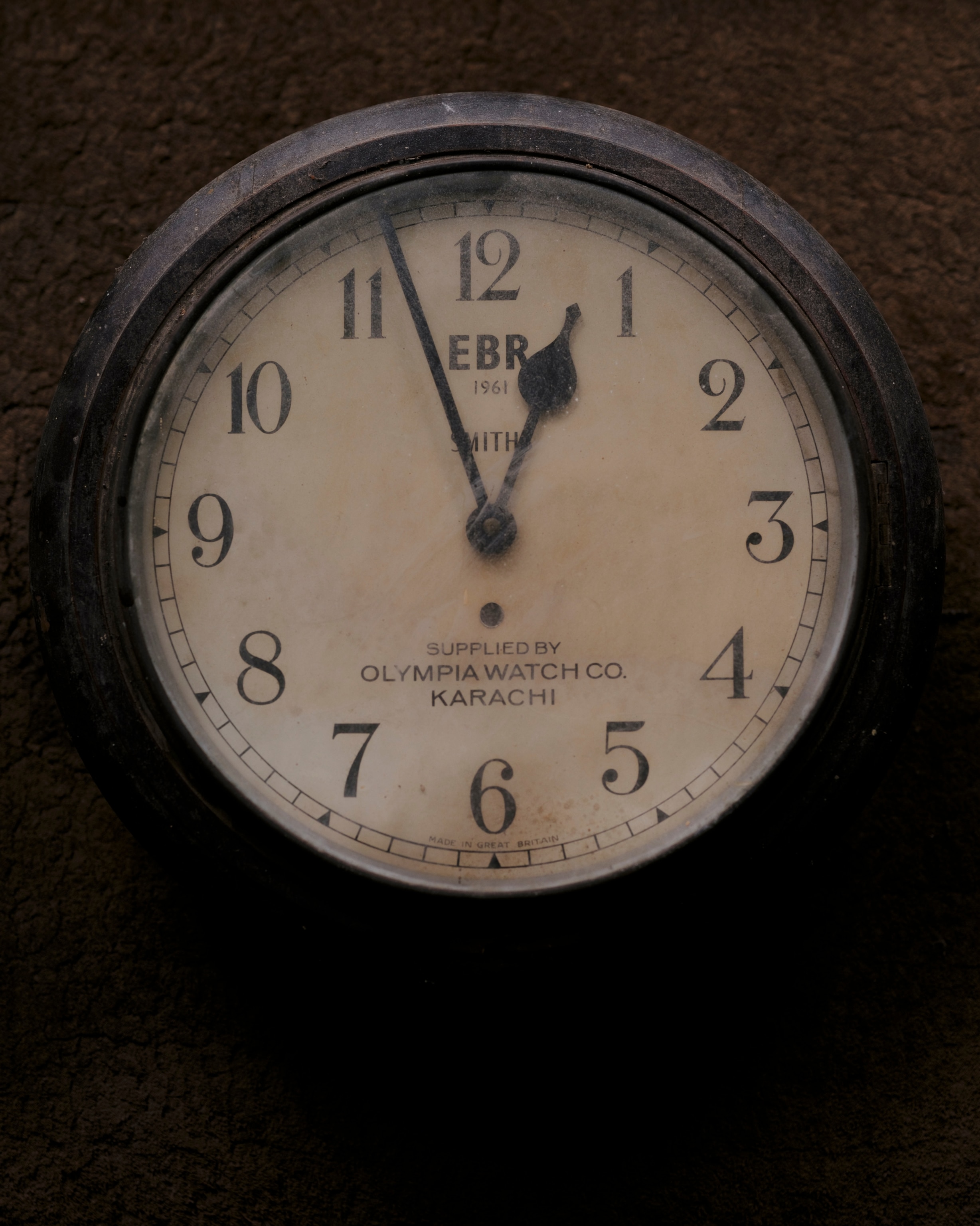

As with his earlier projects, an intense layer of mist and fog lies over many of the images. The opacity of vision and diffusion of light captured by his camera suggests both the end of a story, and a hope for a new arrival. In a coda image of the series, an orange, rain-soaked light envelops the beginnings of a train entering the frame. There are no visible signposts, and I imagine a superimposed palimpsest image of two trains traveling in opposite directions, entering Bangladesh and India at the same time. In the dark of night, the railway carries passengers who don’t want to go home past giant machines whose operators have passed away, and toward a wooden puppet in the shape of the British Queen's palace guards. Watching over this nightscape is a broken clock that tells the right time only twice a day.

Divided Bengal cannot now be united, but the viewer may find in these images the revival of a phantom India-Bangladesh train network, a dream of suturing the open wounds of Partition.