Is Alabama home to America’s oldest Mardi Gras celebration?

In Mobile, Carnival is more than an indulgent holiday. Its time-honored traditions have been passed through generations since the turn of the 18th century.

Finding the roots of when Mardi Gras was first celebrated in America is as complicated as the act of celebrating it today is simple.

Some historians say it first appeared in Mobile, Alabama, pointing to notebooks left behind by Pierre Le Moyne D’Iberville, who chronicled his turn-of-the18th-century journey to locate the mouth of the Mississippi River and made note of a Mass performed on Mardi Gras Day on that voyage. Others, such as Mobile Carnival Museum curator Cart Blackwell, point to a moment decades later, conceding the lack of primary source documents that can confirm anything more.

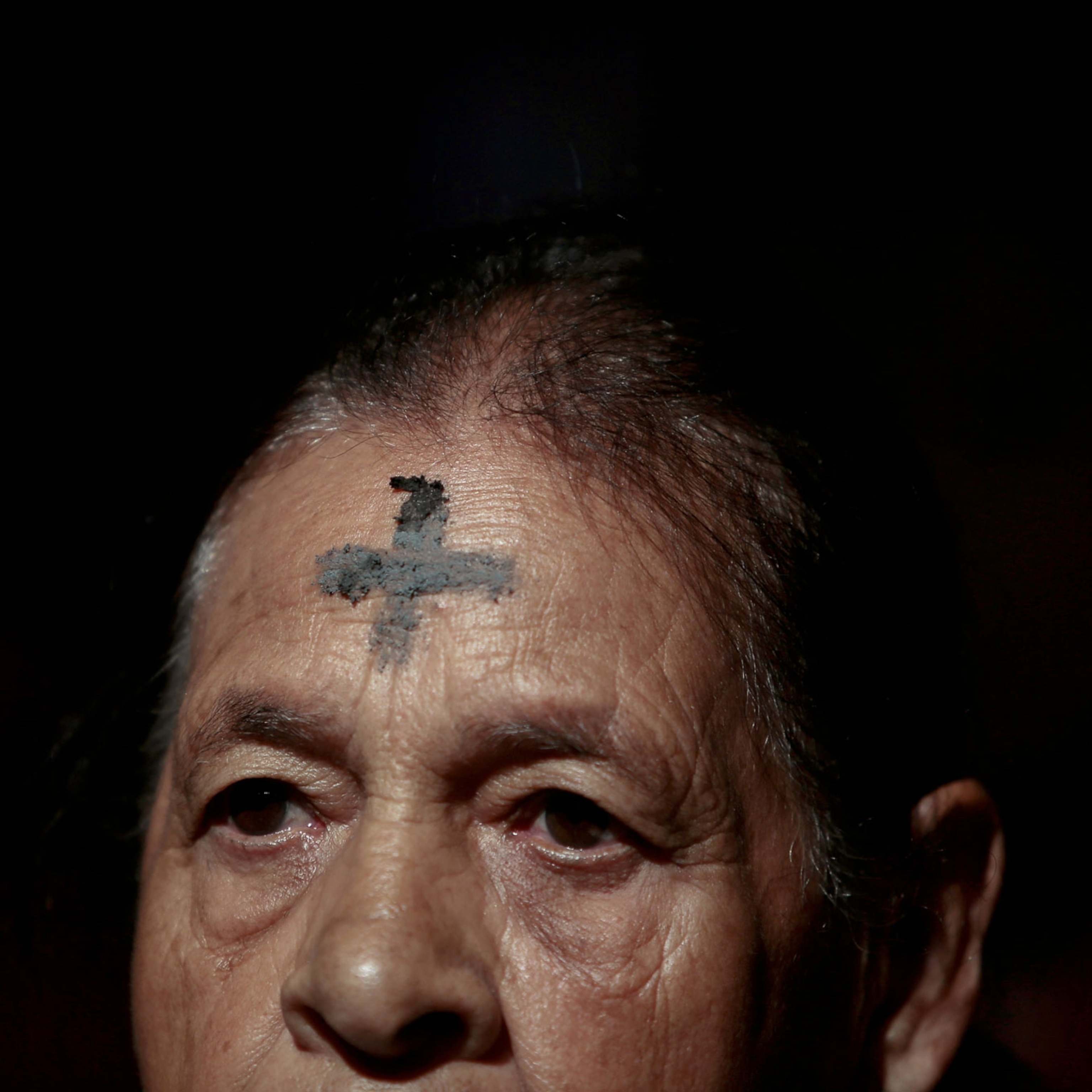

“There are two ingredients people associate with Carnival: The extended season and parades,” Blackwell said, referencing the float-filled street parties during the span of time between the traditional Christian feast day known as Epiphany on January 6 and Mardi Gras Day, which falls on every Tuesday before Ash Wednesday. “In the 1830s, in Mobile, the Cowbellions de Rakin established that format.”

While the precise year matters greatly if you consider the long-held begrudging rivalry between Mobile and New Orleans, both Gulf Coast cities that share French founding and host the two largest Carnival celebrations in the United States, it does not impact what Mobile Mardi Gras historian and local magazine editor Steve Joynt says matters most.

“Everybody participates in Mardi Gras to an equal level,” he said. “People who are into Mardi Gras, they don’t say ‘it’s just for kids,’ they say, ‘I’m going to show my kid how to enjoy Mardi Gras.”

Still, Joynt says, Mobile claims the first American celebration of the type. And, as he notes with a laugh, no other city can prove different.

The annual celebration, with its roots in both early pagan festivals and the Christian tradition of overindulgence before the abstinence brought on by 40 days of Lent, takes place in various cities and regions around the world and with varying displays of artistry. From the decorative masks of Venice to the feather-bedecked, glittering images of Rio de Janeiro or the traditions passed down from formerly enslaved people in the Caribbean, Carnival in all its forms honors the joys of life for those who celebrate it. (See pictures of Carnival costumes from around the world.)

Despite its particularly American reputation for eyebrow raising bacchanalia, spurred on primarily by scenes of barely-dressed adults drinking in New Orleans’ French Quarter streets, Mardi Gras and Carnival, used interchangeably in conversation, find a more family-friendly expression in Mobile. Here, at center stage are the parents and grandparents who take the annual opportunity to teach their next generations something sacred: The bliss of briefly throwing off the cares of the world to spend time with each other.

Still, the way Carnival evolved in Mobile did not escape the history of the city that celebrates it. Located in America’s Deep South, Carnival was first established as a pre-Lenten celebration primarily by the city’s well-to-do residents. Early in the 19th century, that meant, by default, the white members of society.

The Cowbellion de Rakin Society began parading in the streets of Mobile during the Christmas season, establishing a formal way for some of the city’s elite to cut up and make a ruckus in public, and celebrate with a ball and a theatrical tableau, complete with marks of faux royalty, in private. The organization was the first of Mobile’s “mystic societies,” which has traditionally referred to the city’s private Carnival clubs with secretive members’ lists.

During the next few decades, a kind of Carnival cultural exchange between New Orleans and Mobile occurred, resulting in the shift of the celebrations to center around Mardi Gras Day.

“Without New Orleans, there would be no Mobile Mardi Gras,” notes Joynt of the lasting tradition. “Without Mobile, there would be no New Orleans Mardi Gras.”

The Order of Myths remains Mobile’s oldest continuous parading organization to this day, known for its annual Mardi Gras Day procession featuring a parade-leading emblem float with characters playing Folly, who swings pig bladders, and Death. The pair circles each other around a column throughout the night.

Despite its adherence to tradition, Mobile has welcomed some modern updates.

Founded in 1938, the Mobile Area Mardi Gras Association was established by African-American Mobilians. Though it wasn’t the city’s first traditionally African-American Carnival organization, it has established its roots as one of the largest.

“It means a lot to me simply because, in the African-American community, so much of our heritage and traditions were expunged during the enslavement era, so opportunities like this to make connections through generations, to take part in social organizations, provide a nexus between the generations, and also a sense of belonging,” said Joseph Roberson, who served as MAMGA’s King Elexis I in 2007.

That year was also the first that MAMGA’s royalty accepted an invitation from the traditionally white Mobile Carnival Association to attend its ball. The two organizations began a new tradition: Their royalty now attends each other’s balls and acknowledges each other with bows and celebrations.

“I think, on both sides, it opened their eyes to the significance of respecting the traditions of both organizations .... and provided a reference point for both organizations to have a clear view of how each ... celebrates Carnival,” Roberson said. “The reference point led to conversation. The conversation led to changes.” (Is it time to rethink Mardi Gras's use of plastic beads?)

Today’s Mardi Gras celebrations in Mobile continue to evolve. Though the People’s Parade, for example, which began in 1966 after a local author lauded the contributions of a Mardi Gras pioneer named Joe Cain, has been led by the same man for decades, its celebrants seem to constantly find new ways to add to the tradition.

In its early years, though Cain was married to just one woman throughout his life, the parade was joined by women dressed in black as Cain’s many Merry Widows. Then came women dressed in red as the Merry Mistresses. Lately, Cain’s also been mourned by his Secret Misters, according to Wayne Dean, who’s portrayed the Carnival character dreamed up by Cain, Chief Slacabamarinico, for 35 years.

One year, the Mistresses started something of a riot with the Widows and were faux-arrested by local police.

“If you go to the roots of Carnival, that’s what it was about, the flipping of society,” Dean said. “That’s part of the day: It’s street theater.”

And the show comes to a close on Mardi Gras Day when the drama playing out between the characters at the head of the Order of Myths’ parade finally ends and Folly defeats Death.

Every year, said Joynt, “it’s the same thing. And your kid sees that. It’s the same thing you saw, the same thing your parents saw, the same thing your grandparents saw. … Mardi Gras is a keystone to your past, not just your family’s past, but the past of your community, all at the same time.”