Surreal scenes inside Russia’s battle against the pandemic

Patients continue to fill hospitals as rumors and cynicism spread about a vaccine.

When I started to photograph in Moscow, there were these strange processions taking place—priests marching around their monastery with holy water, chanting and singing, praying that Russians would be protected from the coronavirus. One of the priests posted something about this on Instagram, saying they planned to do this every evening. I took a taxi out to the monastery to see them. I was feeling a little weak because I’d been sick myself, three weeks at home. I was just getting healthy again when I went out to watch the priests.

I grew up in Germany, but my mother is from Moscow, so she’s always spoken Russian to me. I’ve been living in Moscow for about a year now—my grandmother passed away unexpectedly, so we have a flat where I can stay. In March I thought maybe I had COVID-19; I had gone back to Germany briefly for work, with a stop in Hungary, and by the time I came home to Moscow I was pretty sick. I didn’t have a fever and I don’t have the antibodies, but I couldn’t smell anything and had a bad cough, especially at night. I stayed in the apartment for two weeks, just in case, reading the news.

It was frightening. Russia closed its long border with China as the pandemic started to spread, but by the time I shut myself in, national news here was starting to report diagnosed cases and deaths. As spring extended into summer, the numbers really climbed. By August 12, Russia was reporting the world’s fourth-largest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, about 907,000, according to data from Russia and international sources. And it was just this week, of course, that we learned Russia is bringing out its version of a vaccine, after very limited testing. (Why Anthony Fauci is skeptical about Russian vaccine.)

But back in March, while I was managing my voluntary self-quarantine, I read and watched news reports and social media. When I emerged, near the end of the month, the case and death numbers were multiplying, and social media was full of rumors that a city lockdown was coming: the subway will close, everything will close, even the supermarkets will close. At one of our local markets people were rushing to buy huge bags of buckwheat—Russians really love buckwheat, it’s the traditional cereal—and already some were wearing masks. Everything looked quite changed.

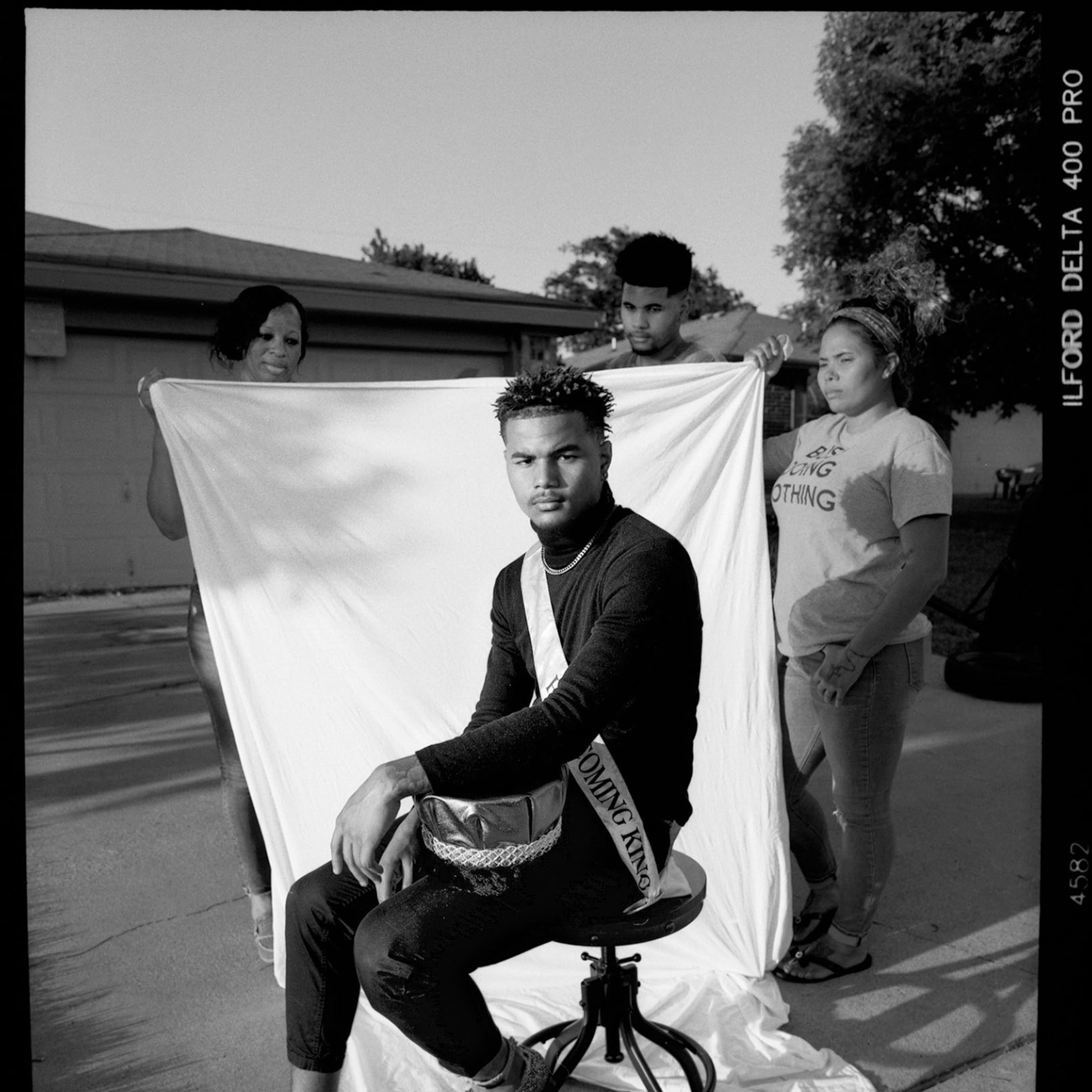

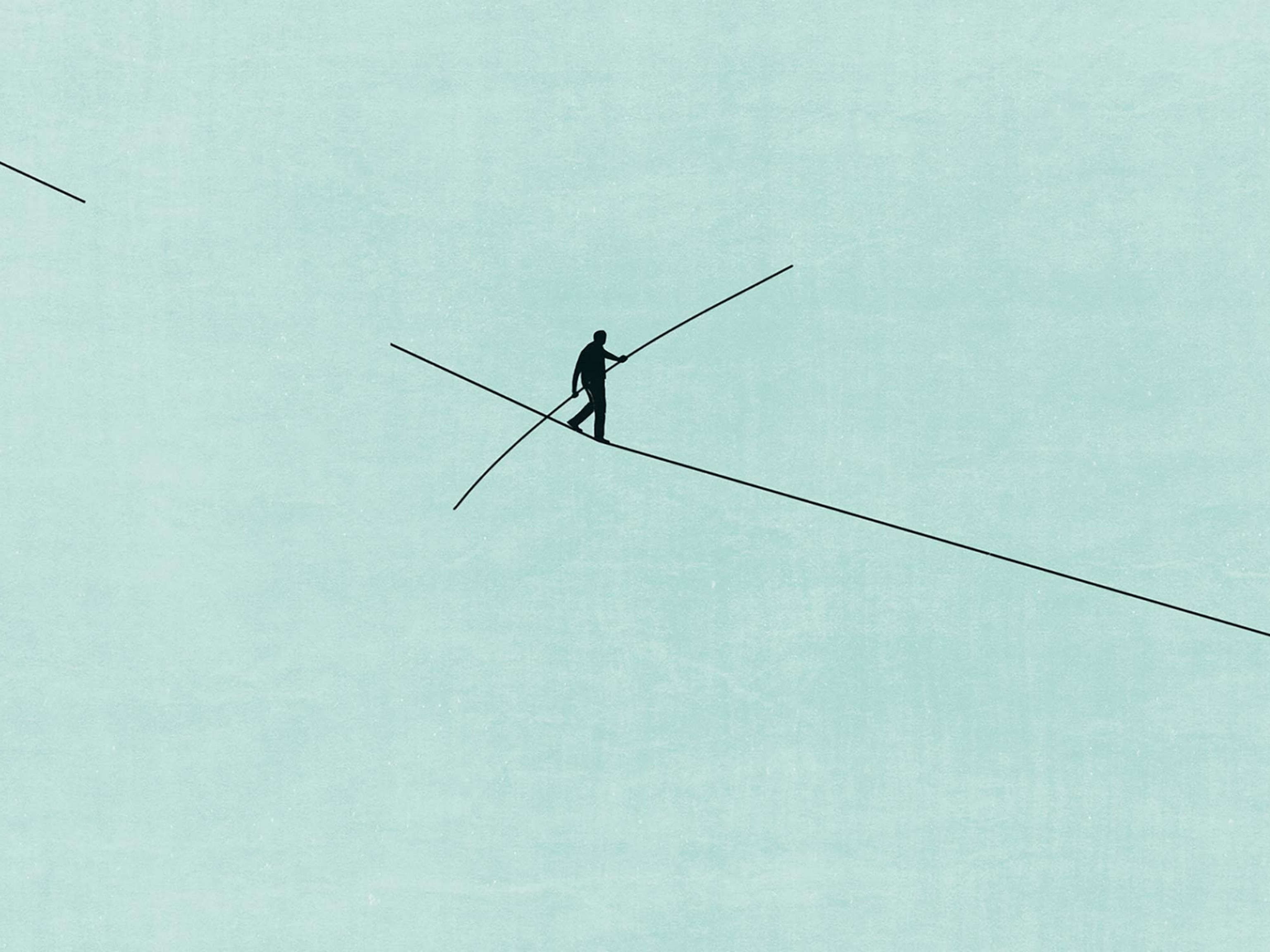

Then on March 29 the city lockdown orders did come. In Moscow people were supposed to leave their homes only for emergency medical care, walking their pets, going to the grocery store, and so on. As a journalist I was allowed to be outside, but at the beginning I was kind of lost; many of us photographers trying to keep pandemic diaries were talking about the same challenges. Empty supermarket shelves, empty streets—how do you photograph a danger you can’t see?

Orthodox Easter was ahead of us, on April 19, the most important holiday of the year in Russia, like Western countries’ Christmas. The mayor of Moscow said churches must not permit the traditional processions or crowded indoor services. “We are at the foot of the climbing curve,” he told reporters. “We’re not even close to the peak.” Those priests sprinkling holy water outside their monastery told me they were eventually forced to stop their evening walks; in mid-April it was reported that a monastery employee had been hospitalized with a suspected COVID-19 infection.

But there was a lot of argument underway, even among religious leaders, about pandemic safety versus the importance of formal group worship. The question of Easter celebrations was left to individual governors. I went to the old city of Tver, about two hours by train from Moscow, where the governor had decided church Easter celebrations could take place as long as special rules were observed.

Marks on the floor were supposed to keep people one and a half meters from each other, and every church I entered had security guards checking for masks, making sure hands were disinfected, shouting at people to stand on their markers. In some places that didn’t work. I saw people singing together, walking around the church, not maintaining distance. I tried to be really strict about keeping my mask on.

I had never been to an Orthodox Easter service before. It’s a beautiful celebration—a magical atmosphere with all the singing and the candles. I made it past midnight but was in bed by 3:00 a.m.; the serious worshippers stayed until sunrise. It seemed suicidal to me that so many elderly people were packed together.

When I visited Moscow hospitals, I found they too were keeping security guards at the doors. All Moscow hospitals have numbers, and Number 52, my first stop, is a collection of a half dozen buildings in a prestigious neighborhood where artists and intelligentsia have historically lived. Usually Number 52 specializes in kidney failure, immunology, gynecology, blood disease, and so on. But by the time I was there it had become a COVID-19 center, like other hospitals in Moscow—all these hospitals devoted to one disease that didn’t exist some months ago.

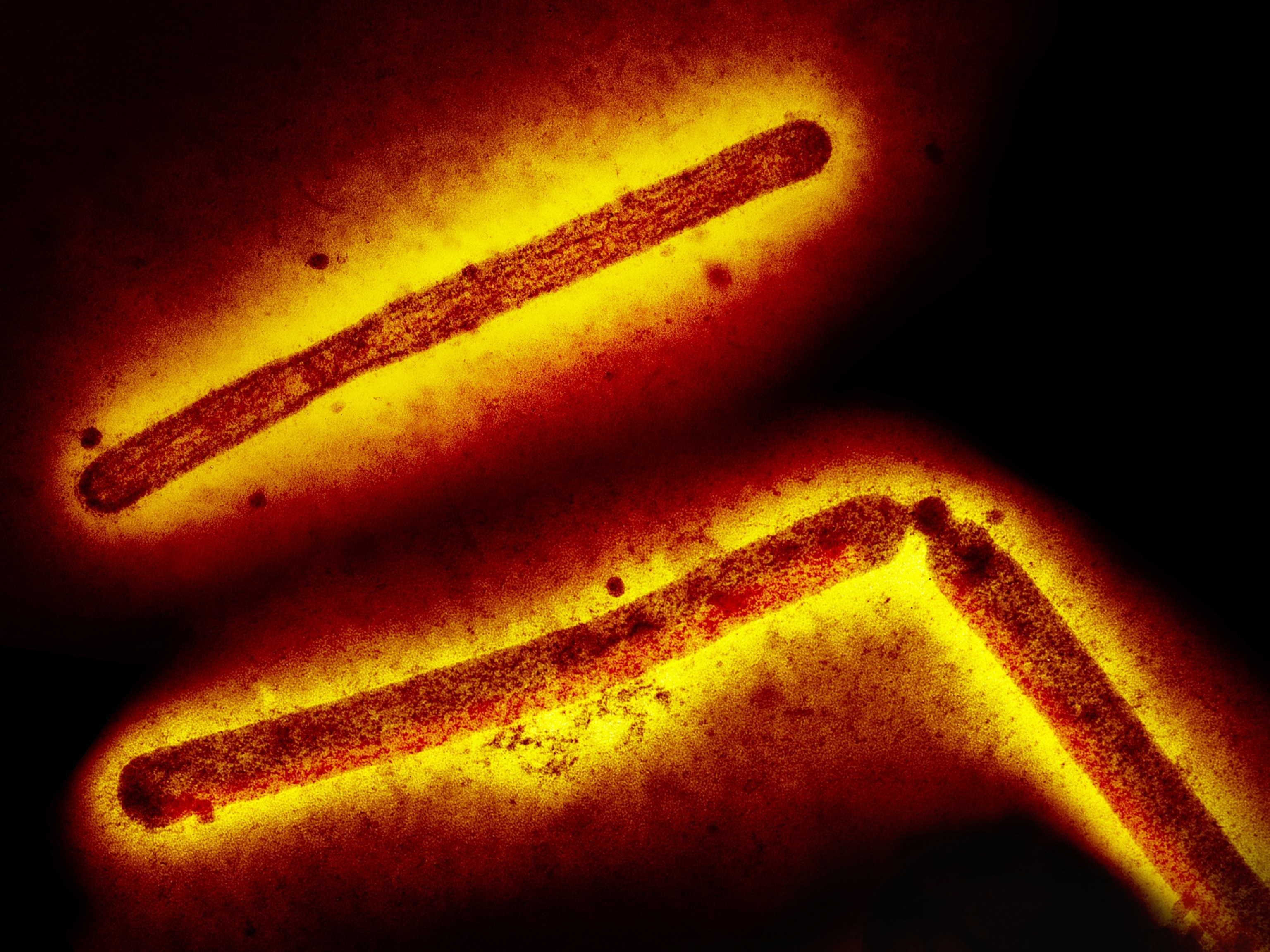

It was shocking inside the hospitals. From the moment you’re in the elevator you’re in a “red zone,” which is considered contaminated. Everywhere is a red zone, really, because the staff transfers patients from building to building. The nurses prepare COVID medicines, infusions, and antibiotics, and rush back to the patients. One patient who had just arrived in the hospital was a boy so sick he needed to be intubated immediately. In the ICU almost no one is conscious; it’s a huge floor where all the old people look more dead than alive. There’s this awkward silence. You see bodies not moving anymore. Some of the bodies turn a strange color. They look like porcelain. (Women are on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19.)

Now, of course, the government has announced this Russian COVID-19 vaccine—that they are making it official for use. For some months the government has been saying how well it was progressing with the vaccine, and there were rumors that some important people had already been vaccinated. On the state-owned channel it’s a big story; they’re saying how good the vaccine will be for Russia’s financial markets, that it’s safe, that President Vladimir Putin’s daughter received it and is doing well, that there’s nothing to worry about.

On Russian Twitter I’m seeing a lot more cynicism and sarcasm.

“Our vaccinations didn’t undergo all necessary tests. What do I not understand?”

“Oxford vaccine—42,000 volunteers for the third phrase of trials. Russia—76 people, there is no third phase (!!).”

“Everyone who did not die from COVID will be killed by the vaccine.”

A former statesman and Central Bank chairman said Putin is willing to experiment with the entire Russian population in order to protect himself politically. My Russian boyfriend’s father tells me he definitely would not like to be in the front row as people start getting vaccinated. And one of the hospital doctors I met just wrote me: “At best it’s safe. At worst, useless. Under no circumstances would I take it.”

What's it like here now? It's almost like COVID-19 doesn't exist anymore. For a while they did start fining people who weren’t wearing masks in the supermarkets or on trains, but I think this was like one-time actions. It seems as though nobody wears the masks. Even bartenders don't really wear masks. In Russia everyone was joking about how people in power were trying the vaccine first on themselves. But if it works—if it's tolerated—I would like to have it too.