To carry iron to the world, Brazil’s 500-mile rail disrupted countless lives

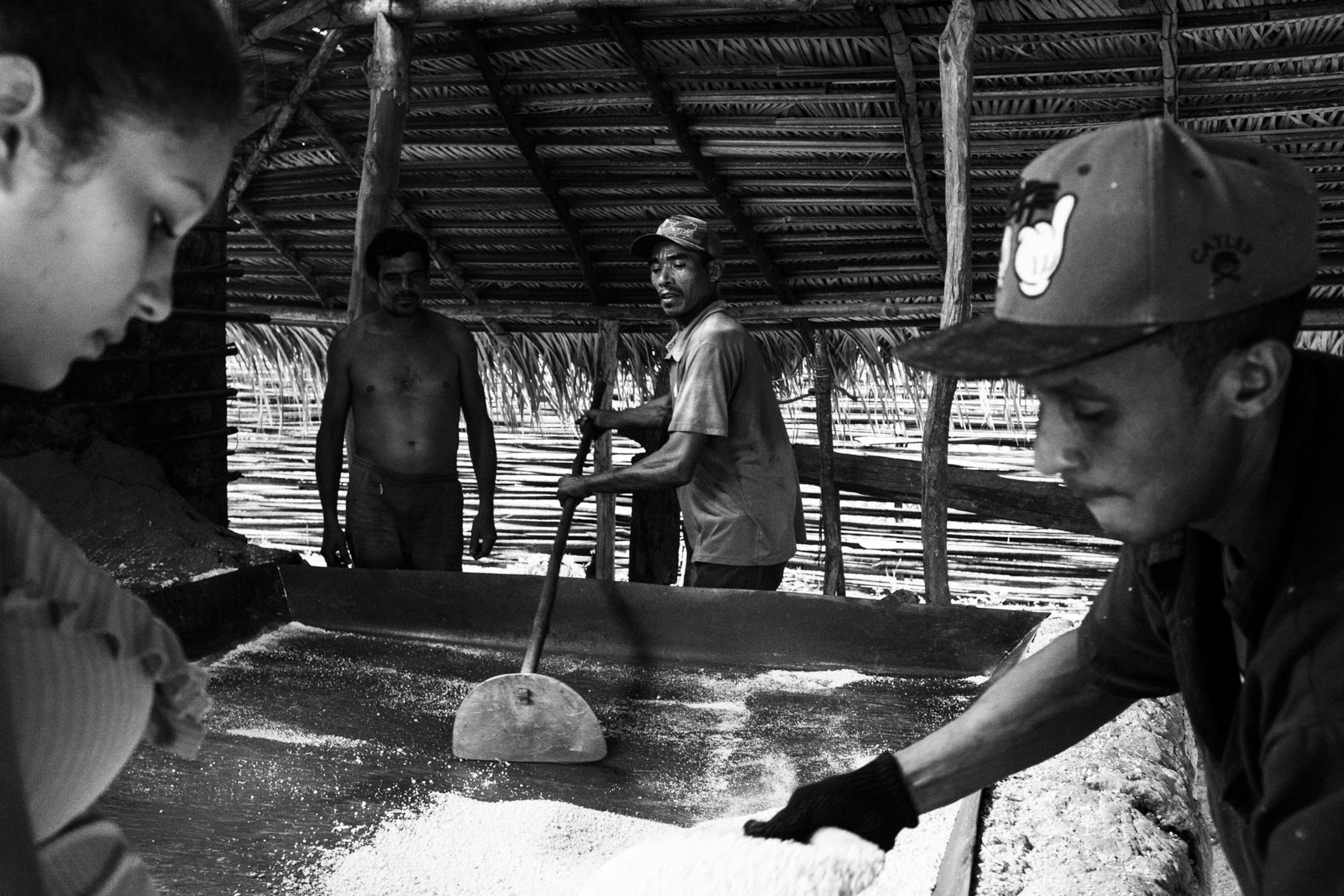

Photographer spent years documenting communities transformed by a freight line that cuts across a mountainous jungle to reach seaports on the Atlantic Ocean.

At the edge of the Amazon rainforest state of Pará, in north-central Brazil, sits the largest iron ore pit mine on the planet. Extracted from the depths of the Mina de Carajás are metals found in everyday appliances and items around the globe.

The Carajás mine produces so much raw material in a year—some 100 million metric tons in 2020 alone—that in today’s world it is nearly impossible to avoid its gray, sooty stamp, shined and sparkled by the laundry machine that is often long-distance global trade. But how does so much iron get from a mine in the middle of the forest to a seaport as steel, where it can then be shipped to the furthest corners of the world?

The answer is a 550-mile railway, which stretches from the mine, deep in the mountainous jungle, to the port of Ponta da Madeira in São Luís, at the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. The train carries ore in its metal boxcars as it traverses the land and soars over rivers across tall trestles, stopping at steel refinery plants along the way.

The Greater Carajás Project, as the entire industrial system surrounding the mine and the railway is known—and Vale S.A., the Brazilian mining company in charge of it—has faced scrutiny from international human rights and environmental organizations for alleged abuses and violations that have transformed life for the many communities along its path.

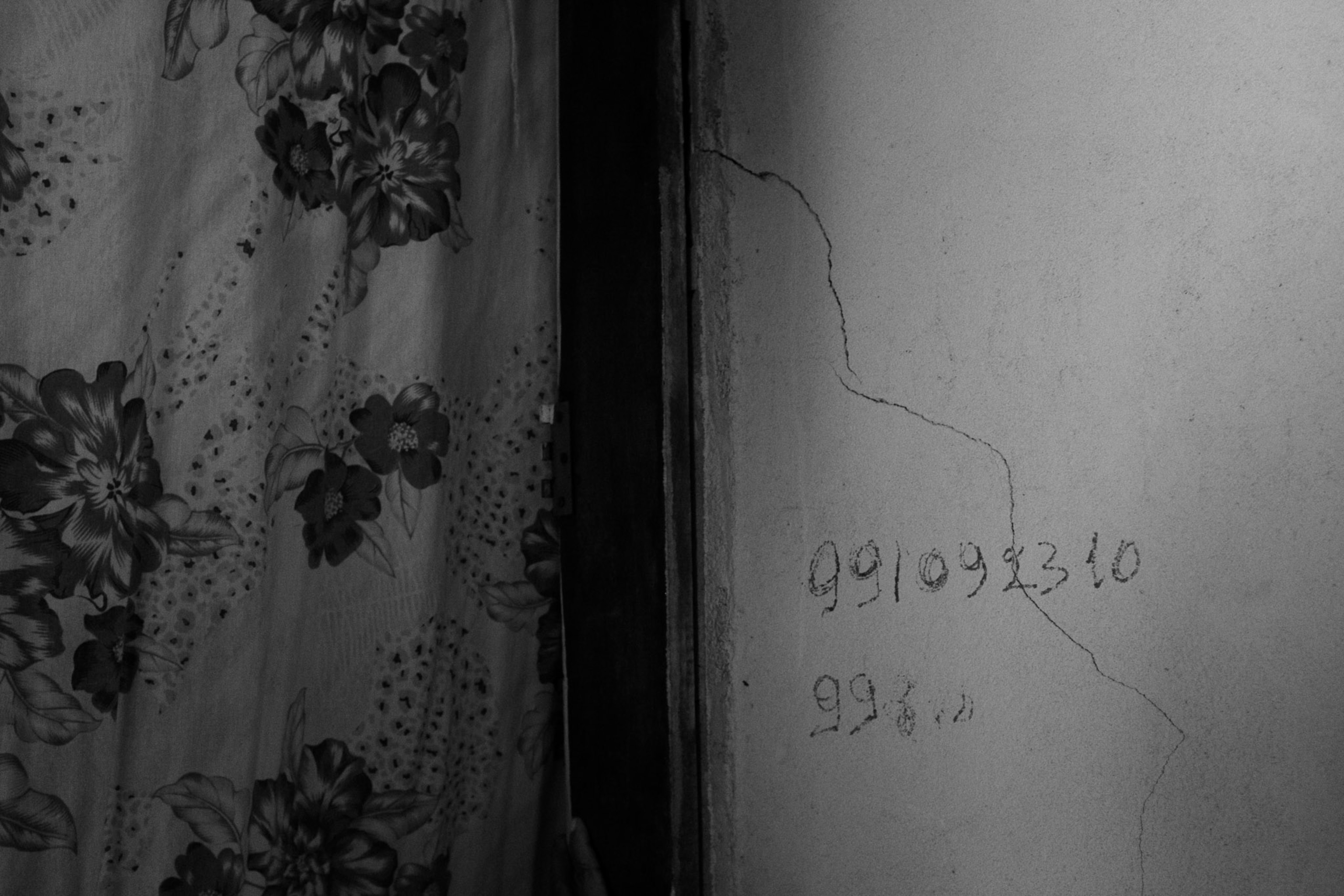

Some homes have been deemed structurally unsound due to the constant rumble of the train; others have been removed to make way for construction, leaving people internally displaced. Residents precariously crossing the tracks in places where there is no safe passage have been run over.

In Piquiá de Baixo, a particularly affected town where steel mills were built in the 1980s, some 65 percent of community members now suffer from respiratory problems, according to a 2012 study by the International Federation for Human Rights that was cited in a 2020 UN report following the Human Rights Council’s visit to the region. Others have had ophthalmological and dermatological diseases and burns caused by improperly disposed residue and toxic waste from “pig iron,” an intermediate product from the processing to steel.

Brazilian photographer Ian Cheibub has spent several months over the course of the past three years following the railroad and spending time with these communities along the tracks. Shot originally in black and white, the images portray a world transformed by the cargo railroad.

Ian Cheibub is a visual storyteller based in Brazil. He currently works covering stories in Brazil for international media outlets. His photo and video works have also been published on GEO Magazine, Der Spiegel, The Guardian, De Volkskrant, STERN, VICE, NRC, among other outlets.