A German werewolf's 'confessions' horrified 1500s Europe

Under torture, Peter Stumpp confessed to savage crimes—leading to perhaps the harshest trial during Germany's werewolf panics.

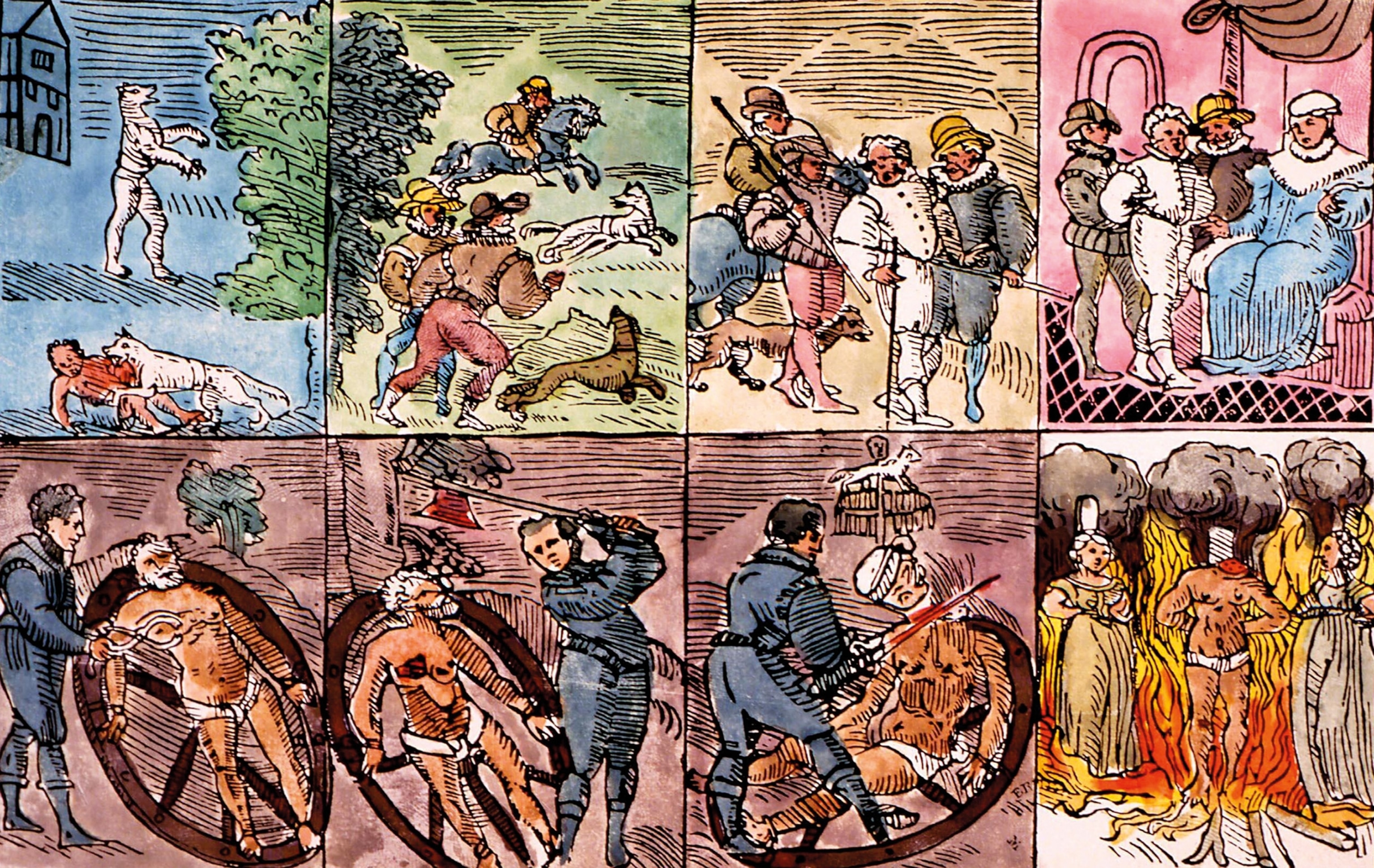

On October 31, 1589, a large crowd gathered in the German city of Bedburg, near Cologne, to witness an execution. The condemned man was Peter Stump, a 50-year-old farmer who had confessed to making a pact with the devil. He wasn’t seeking riches; he wanted the ability to turn into a werewolf. His shocking crimes included multiple murders and cannibalism. Of the 16 people he killed, 13 were children–his own son among them, whose brain he allegedly devoured. He also admitted to having had sexual relations with his daughter and with a succubus (a demon in the guise of a beautiful woman). “Of all other that ever lived, none was comparable unto this Hellhound,” an account of his execution said.

Stump (called Stubbe and Stumpf in some sources) suffered terribly during his execution, one of the most brutal on record. He was strapped to a wheel and skinned alive. His bones were broken. He was decapitated and then his body burned at the stake. As a warning, his head was impaled on a post in the center of the village.

(How did medieval Europe envision the devil?)

Modern monsters

Wolves and witches

The lurid nature of Stump’s crimes and punishment captured the public imagination. Although Stump’s trial and execution stand out, his was not an isolated case. Between the 15th and 18th centuries in Europe famine, plague, war, and religious struggle gave rise to superstitious beliefs, which included fears of witches, usually women, and werewolves, typically men.

Accusations of lycanthropy were often intertwined with—but far less frequent than—witchcraft. In some areas of Europe there is no record of werewolf trials at all. In England, where wolves were almost completely eradicated in the 16th century, there are no records of werewolf trials. Nor are there any in the Mediterranean region of Europe.

European werewolf panics were centered in areas with wild wolves, forested regions, as well as a strong culture of livestock herding, such as Germany and France. Fears of real wolves preying on animals and children grew into fears of demonic wolves. If rabid wolves were present, werewolves might be blamed for their “crimes.”

(Did a "werewolf" really terrorize France in the 1700s?)

The most comprehensive list of werewolf trials in early modern Germany contains about 300 cases. While not inconsiderable, that number pales in comparison with the 30,000 to 45,000 executions for witchcraft in Germany during the same period.

Accused werewolves were mostly, but not exclusively, male, and most were shepherds. “Wolves were viewed as strong, violent, and aggressive, traits usually associated with men,” said Brian Levack, professor emeritus of history at the University of Texas at Austin. In most contemporary accounts about Stump, the man transformed himself into a wolf by wearing a wolfskin belt given to him by the devil. By removing the belt, Stump could return to human form. Levack points out that werewolves all used some instrument to effect their transformation, which is typical of male witchcraft. “All of them used some sort of instrument in their magic, such as Stump’s use of a magical belt ... whereas the lower forms of village magic allegedly practiced by female witches consisted mainly of charms, curses, or various concoctions.”

Stumped for detail

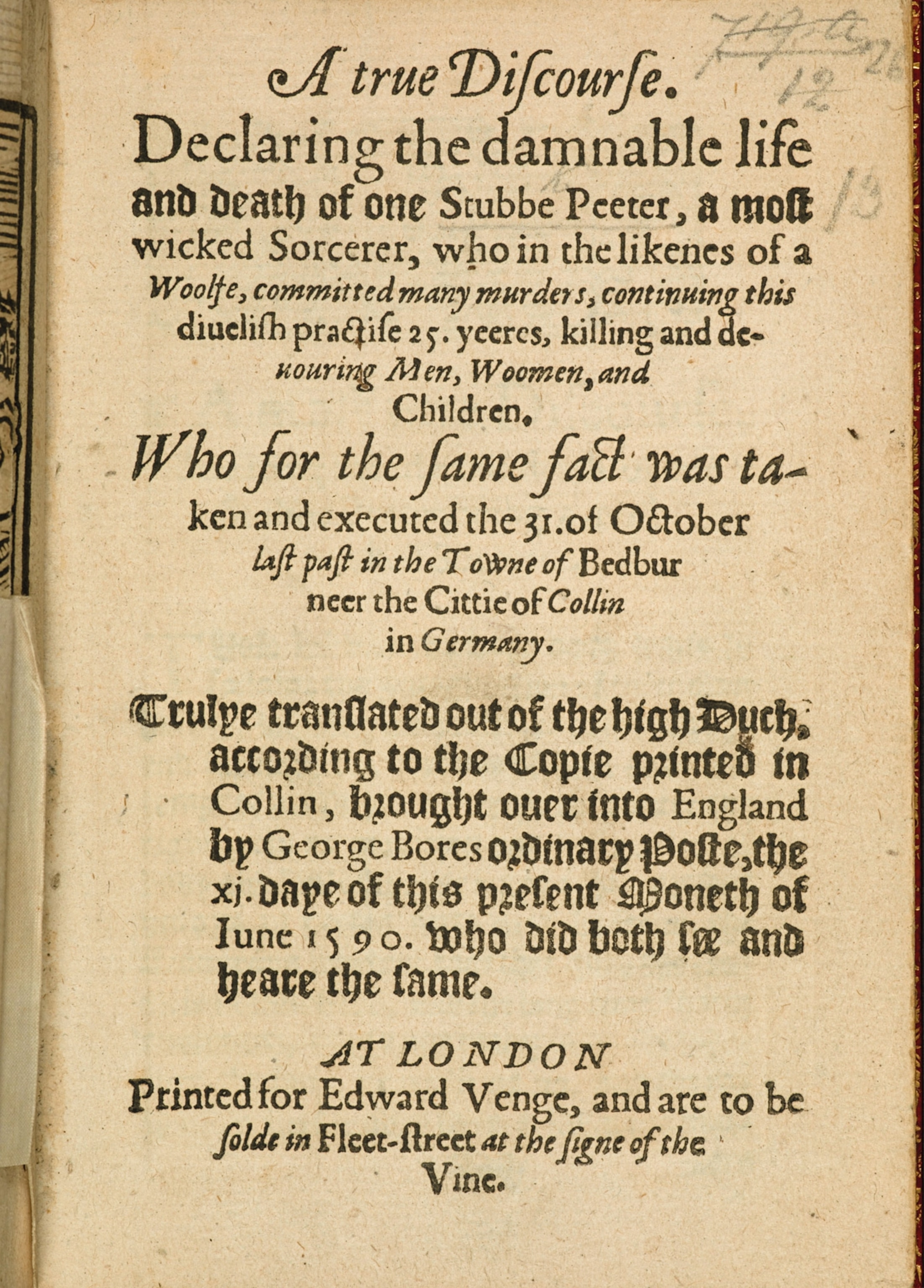

Despite the curiosity stirred up by the trial, the historical evidence left behind of Stump’s ordeal is thin. No interrogation transcripts or court records from the trial have survived. For details about Stump, historians must rely on a collection of pamphlets and handbills. The longest is an English pamphlet published in 1590; the 16-page text asserts to be a translation of a German work, but historians have not found the original document.

What is understood about Stump’s life largely comes from these accounts, although there is little agreement among them. Even his exact name varies, some even claiming that he got the name Stumpf (German for “stump”) because he lost his left hand in an accident.

Scholars are unsure when Stump was born, but his occupation is consistently given as a farmer. He is said to be from Epprath, a village near Bedburg. Some scholars suggest Stump was a wealthy land-owner, based on a description in the 1590 English pamphlet:

[H]e would go through the streets of Cologne, Bedburg, and Epprath, in comely habit, and very civilly, as one well known to all the inhabitants thereabout, and oftentimes was he saluted of those whose friends and children he had butchered, though nothing suspected for the same.

This detail is likely nothing more than dramatic color, however, since no other source exists to confirm it.

(Witch panics killed thousands throughout history.)

Motivations

It is from these salacious sources that details of the Stump affair must be drawn—although supernatural elements in the story are given as fact. In one version Stump is arrested after a local farmer enters into a fight with a wolf and cuts off its left paw with a sword. When the farmer later encounters Peter Stump, the farmer sees that Stump is also missing his left hand—which is enough to arouse suspicion that Stump and the wolf are one and the same entity.

In the English pamphlet Stump’s arrest is more dramatic. After a series of murders and livestock deaths, villagers form patrols. Stump is spotted while in his wolf form and chased by them. Stump removes his magic belt and reverts to human form in full view of his pursuers. Once his identity is confirmed by the mob, he is arrested.

Stump’s guilt hinges on his subsequent confession, which was secured under torture and threat of future torture: “Thus being apprehended, he was shortly after put to the rack ... but fearing the torture, he voluntarily confessed his whole life.” Some historians believe it’s possible that Stump was a murderer (one has even posited that the werewolf legends originated in attempts to explain the presence of serial killers). Even if he was not, it is likely that any local wolf attacks on livestock or people were attributed to him as well. Another historical factor might well have made Stump a scapegoat. His alleged crimes coincided with a period known as the Cologne War (1583-88), a conflict between Protestant and Catholic factions. Roving mercenaries terrorized the region. Unsolved crimes could have prompted sinister folk stories of a werewolf prowling the forests. Consequently, Stump may have been singled out to ritually purge the community of evil through his execution.

(Accusations of witchcraft persist in the 21st century.)

Religious disputes also provide another possible interpretation of Stump’s crimes. By 1589 the Catholic faction had secured control of the Bedburg region. A brutal trial would dissuade Protestants from thoughts of rebellion, buttressing the Catholics’ claim to power. Stump, who allegedly converted to Protestantism, may have seemed a fitting example.

Some scholars allow for the possibility of this view, but Levack disputes it. “Stump was prosecuted not as a warning to other Protestants but because he had been accused of being a moral reprobate, regardless of his religious allegiance,” he said.