Witch panics killed thousands throughout history

Joan of Arc and Anne Boleyn are two of history's most famous accused witches, but like the majority of those put on trial for witchcraft, mass hysteria and superstition doomed them to their grisly fates.

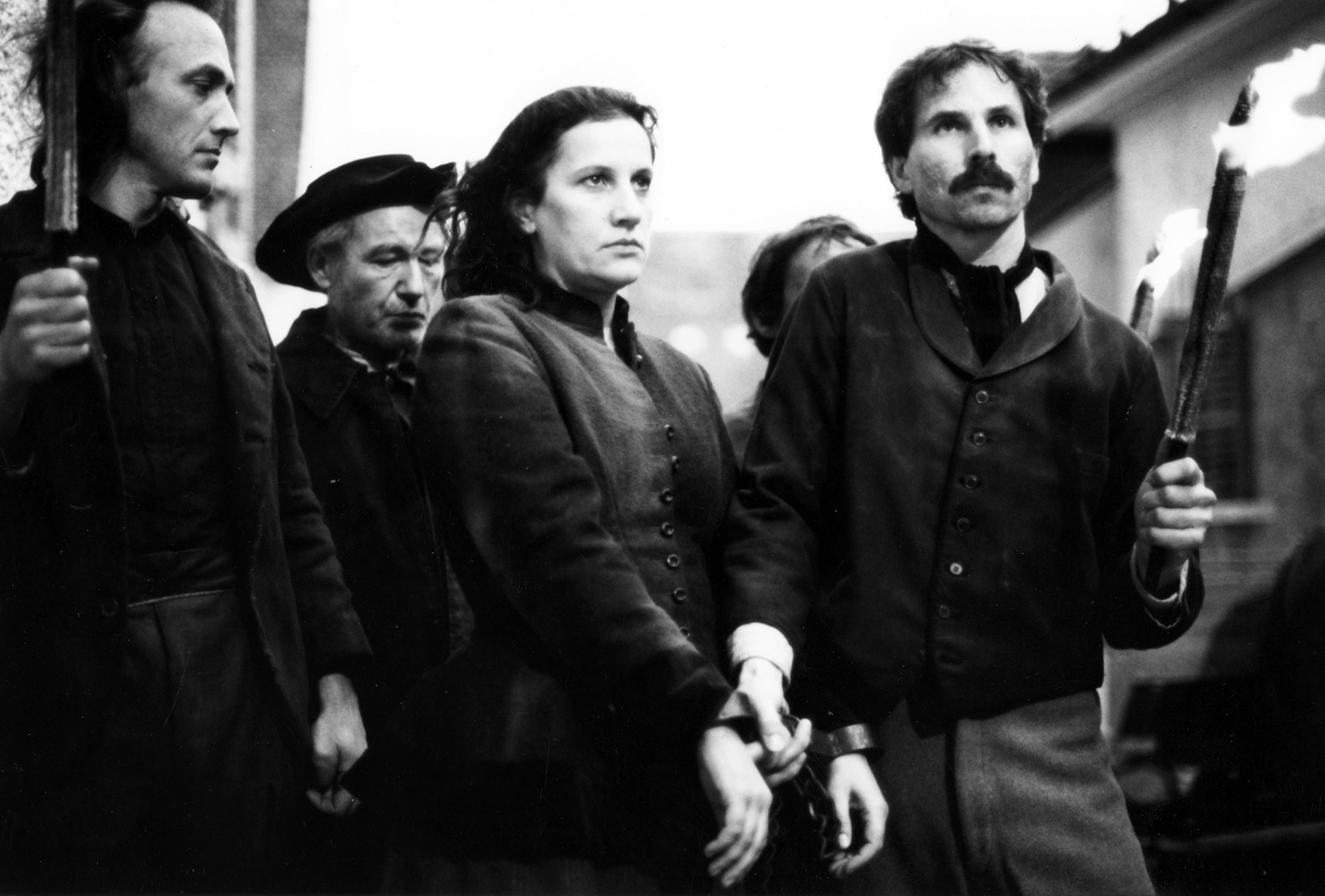

Among history's most notorious events, witch trials resulted in the torture and death of thousands of people, most of them women. Some of the most famous witch trials took place in 15th-century France, 16th-century Scotland, and 17th-century Massachusetts. In all of them, victims were wrongfully condemned as witches, often tortured, and then put to death, a history that is fascinating—and horrific.

Ancient healers and enchantresses

The notion of witchcraft—manipulation of everyday events using magic—dates back to ancient times. The 18th-century B.C. Code of Hammurabi contains penalties for witchcraft. Generally witches could be either good or bad, practicing so-called white magic to help people or black magic to hurt them.

Often practitioners were women, whom neighbors would call on them to cure sickness, aid mothers in childbirth, and recover lost objects. But women like these could also be blamed for bad events—sickness and death, storms and earthquakes, or droughts and floods.

Some wielders of such powers were even worshipped as deities, as in ancient Greece. As the main Greek goddess of magic and spells, Hecate possessed control over the earth, the heavens, and the seas. And the Greek enchantress Medea helped Jason and the Argonauts acquire the Golden Fleece, the magical woolen coat of a flying ram.

But while some of these magical practitioners were good, those who were thought to cast ungodly spells, shape-shift, and pervert the laws of the heavens elicited fear. The Bible warns against such evil, with the Book of Exodus commanding: “You shall not permit a witch to live” (Exodus 22:18) and Leviticus “A man or a woman who is a medium, or who has familiar spirits, shall surely be put to death; they shall stone them with stones. Their blood shall be upon them” (Leviticus 20:27)

European toil and trouble

Things did not get easier for witches in the Middle Ages. The Black Death in Europe wrought devastation and religious wars that made people believe in malevolent unnatural forces—such as witches and werewolves—were at play destroying society.

Witches became an easy scapegoat for many popes, notably 15th-century Innocent VIII, whose inquisitors mostly targeted women since the church believed Eve had originated sin in the Garden of Eden. Authorities rallied citizens to ferret out the guilty, and accusations of witchcraft sprang from mundane events such as petty arguments and grievances. Torture, to gain confessions, followed. Once the tormentor broke the victim’s will, the authorities forced them to name others and then had all hanged or burned at the stake.

Joan of Arc, a peasant girl living in medieval France during the Hundred Years’ War, heard voices telling her to fight the English. Dressed as a warrior, she helped liberate the city of Orleans, invigorating the French troops' morale. When the English later captured the 19-year-old Joan, they accused her of witchcraft and burned her at the stake in 1431. Pope Benedict XV canonized Joan in 1920, making her the only person to be condemned as a heretic and then recognized as a saint.

(How Joan of Arc turned the tide in the Hundred Years War.)

Witchcraft in Britain

Witchcraft in the British Isles reached some of the highest echelons in the land. Anne Boleyn, the wife of Henry VIII for whom he broke with the Catholic Church in 1533, did not bear him the male heir he desired. Found guilty in 1536 of adultery and treason, Anne was beheaded at the Tower of London. After her execution, Anne was accused of being an 11-fingered witch, though when her remains were exhumed in the 19th century, no extra digit was discovered. After Anne's death, Henry VIII created the Witchcraft Act of 1542, England’s first law outlawing black magic.

(How did Anne Boleyn win over Henry VII?)

In Scotland, witchcraft became a crime, punishable by death, in 1563. Decades after its passage, King James VI of Scotland would bring vast death to the British Isles in the 1590s when his obsession with black magic began one of Europe's worst witch hunts. When his bride Princess Anne of Denmark sailed to Scotland to marry James, a tempest battered her ship. The king blamed witches and rounded up people in North Berwick, Scotland, where inquisitors used torture to extract confessions.

Among the arrested unfortunates was midwife Agnes Sampson. Examiners shoved into her mouth a scold’s bridle with four sharp prongs and forced her to admit to trying to kill the king. Strangulation followed, making her one of about 70 people killed in this event that went on to inspire the three witches in Shakespeare’s Scottish play Macbeth.

Colonists on trial

In North America, English colonies also held their own witchcraft trials, most famously in Salem, Massachusetts. In 1692 several girls there began having violent fits. The local doctor diagnosed bewitchment, and they were brought to trial. The ensuing mass hysteria saw suspicious and resentful neighbors, mostly young females aged 11 to 20, accusing one another of being witches—resulting in the trials of at least 150 people with little recourse, including a four-year-old girl.

Many were forced to pay fines and make a public apology, while some were jailed for months and tortured. Nineteen ended up being hung and another pressed to death. The Massachusetts General Court later annulled the guilty verdicts, but that did little to assuage the affected families, and resentment and bitterness lingered for centuries.

Europe's last witch?

Anna Göldi worked for a family as a domestic servant in Glarus, Switzerland. They accused her of causing one of their daughters to vomit metallic objects. Göldi was executed in 1782, and she holds the unenviable distinction of being the last person killed for witchcraft in Europe. In 2008 local authorities cleared her of all charges, and in 2017 the town opened a museum dedicated to her and the period.

The trials diminish

Witchcraft trials on both sides of the Atlantic began to die out after the 18th century for the most part—though what was deemed the second Salem witch trial took place as late as May 14, 1878, when a Christian Scientist was accused of hypnotism. Not all witches were women. A follower of Mary Baker Eddy of the Christian Scientists, Daniel Spofford helped heal a 50-year-old invalid, Lucretia Brown, whose spine had been injured as a child. At first Brown claimed Christian Science had healed her, but when she relapsed, she accused Spofford of using “mesmerism,” or hypnotism, to negatively affect her health. The trial became Salem’s last witchcraft trial, taking place on May 14, 1878, nearly two centuries after the original witchcraft hysteria. The judge dismissed the case.

Belief in witchcraft persists even into the 20th century. During World War II, New Forest Coven, a group of alleged witches gathered at Highcliffe-by-the-Sea, England, to cast a spell on Adolf Hitler on August 1, 1940. Modern Wicca founder Gerald Gardner wrote his 1954 book Witchcraft Today how the group’s goal was to cast a spell to protect the British Isles from the invading Nazis. Their ritual, as recounted by Gardner, became known as Operation Cone of Power.

Around the world today, fears about witchcraft and supernatural powers have not completely faded. In the United States, the "Satanic Panic" of the 1980s and '90s stirred up baseless conspiracy theories and accusations of black magic ritual abuse across the country. In the early 2000s, fears of witchcraft were instigating violence and death in countries like Papua New Guinea and Nigeria. As science continues to progress and superstition falls away, perhaps the fears of modern-day witches will truly become a thing of the past.

To learn more, check out Science of the Supernatural. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.