India's warrior queen didn't back down from the British

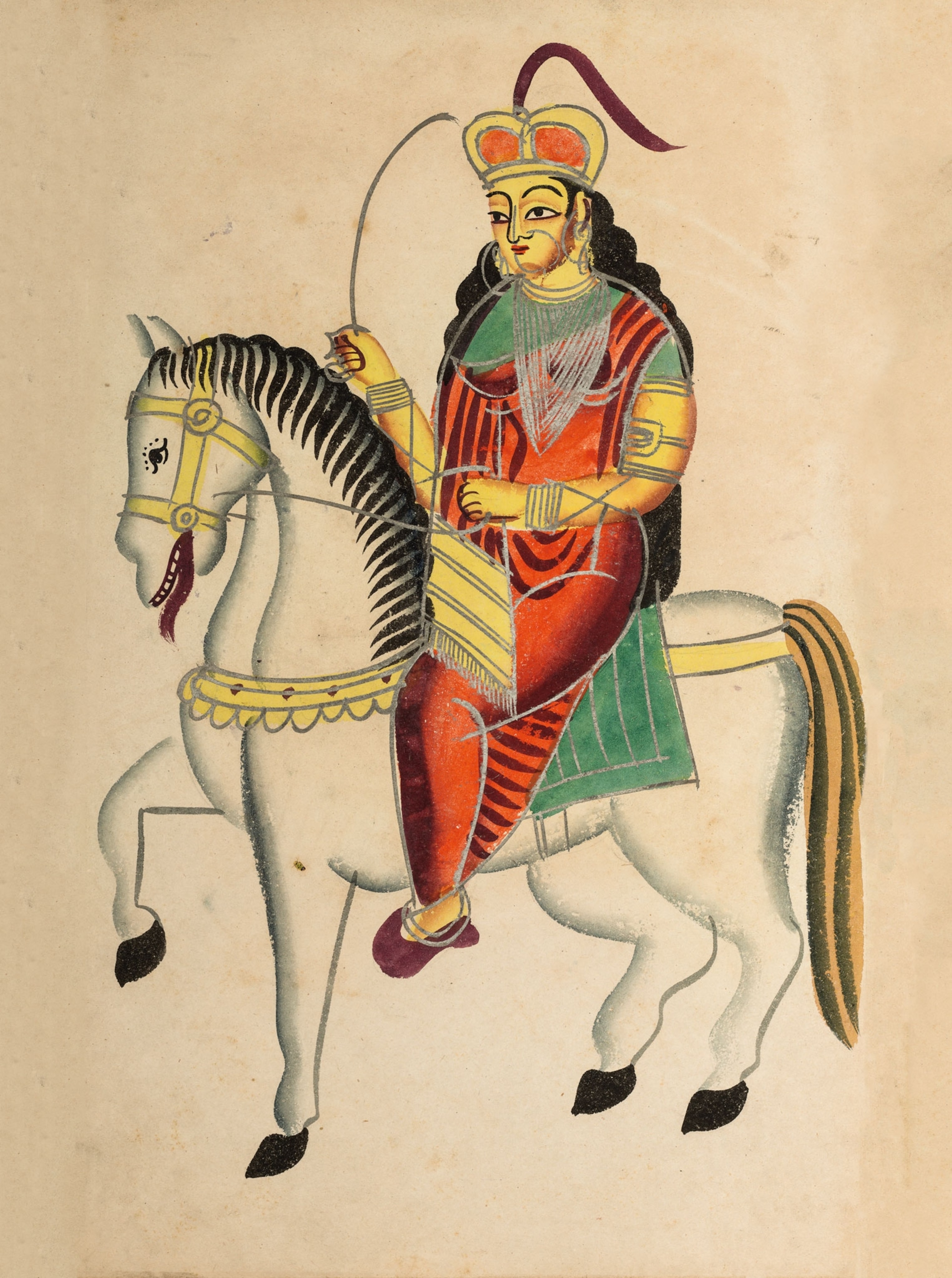

Lakshmi Bai, the "rani of Jhansi," fought back against Britain's plan to annex her kingdom in the 1850s and became an icon of freedom in India.

There is something of the Cinderella story to Lakshmi Bai, a commoner who rose to become rani (queen) of Jhansi, a princely state in mid-19th century India. Most fairy tales would end there, but in Lakshmi Bai’s case it was just the beginning of a remarkable life as a warrior queen.

After becoming regent in her mid-20s in 1853, she would find herself at the heart of the Indian Rebellion that broke out in 1857, now known by many historians as India’s First War of Independence. Ultimately, she would lead thousands of infantry and cavalry troops into battle against the British, reportedly fighting with a sword in each hand and her horse’s reins between her teeth.

History and myth are inseparable in her story. In the end, Lakshmi Bai, the rani of Jhansi, would lose her kingdom and die in battle but become an inspiring symbol to the anti-colonial struggle that culminated in Indian independence 90 years later.

Rebel regent

Lakshmi Bai was born around 1827 in present-day Varanasi in northeast India. Named Manikarnika, she was the daughter of a Brahman who worked as an adviser to the court of the peshwa, or prime minister, of the Maratha Empire, Baji Rao II. Though not aristocratic, Brahmans belonged to a higher caste of priests and scholars. When Manikarnika was four, her mother died, and she moved to court with her father. The peshwa raised her like his own; she received an education unlike most girls and trained with the boys in martial arts, fencing, and riding.

In 1842 the young Manikarnika married the much older Gangadhar Rao, the maharaja, or king, of Jhansi. After the wedding, she changed her name to Lakshmi Bai in honor of Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth and good fortune. The couple did not find fortune in starting a family, however, and their biological son died when he was only a few months old. In 1853 the maharaja became ill. Following Hindu tradition, the couple adopted a five-year-old boy named Damodar Rao, the son of a relative, and declared him to be heir to the Jhansi throne. The maharaja then instructed that Lakshmi Bai would rule as regent until the boy came of age. Shortly after the adoption, Lakshmi became a widow. (Meet 10 of the hardest working moms in history.)

The East India Company, seeking to replace the Indian aristocracy with British officials and expand the British Empire, had a ploy to exploit such situations: the doctrine of lapse, a policy that gave the corporation the right to annex any kingdom whose ruler did not have a natural-born male heir. Lakshmi Bai was offered an annuity of 60,000 rupees in compensation for her departure, which the young queen refused, declaring, “I will not give up my Jhansi.”

Face of the queen

John Lang, an Australian lawyer, represented Lakshmi Bai in her legal battle against the East India Company to stop the annexation of Jhansi. In his memoir, Wanderings in India, he describes seeing the rani for the first time: “She was a woman of about the middle size—rather stout, but not too stout. Her face must have been very handsome when she was younger, and even now it had many charms . . . The expression was also very good, and very intelligent. The eyes were particularly fine, and the nose very delicately shaped. She was not very fair, though she was far from black...Her dress was a plain white muslin, so fine in texture . . . that the outline of her figure was plainly discernible—and a remarkably fine figure she had.”

Revolt of the sepoys

As she took control of her kingdom and organized her forces to fight the colonialists, a revolt by Indian soldiers, or sepoys, in the company’s army, which began to the north in Meerut, caught fire. Rather than a single cause, the revolt had been stoked by an accumulation of grievances over what was seen as a British attempt to undermine traditional Indian society and religion.

The spark that lit the fuse was provided by rifle cartridges allegedly greased with pig and cow fat, which the sepoys had to tear open with their teeth before loading. Consuming pork and beef violates dietary laws of Muslims and Hindus, respectively. Although there is no evidence that either material was, in fact, used, the company had upset religious sensibilities on previous occasions. It had abolished sati in 1829, the Hindu custom of burning widows alive with the corpses of their husbands. The company had supported Christian missionary activity for decades, while an 1850 law allowed converts to Christianity to inherit ancestral property, which effectively promoted Christianity over the Hindu faith. (Watch Morgan Freeman learn about Hinduism's millions of gods.)

Sati was supported by some conservative, upper-caste Hindus as a path for widows to show full devotion to their deceased husbands. However, Lakshmi Bai’s decision not to carry out the practice would not necessarily have been seen as inappropriate by all Hindus. According to Harleen Singh, author of The Rani of Jhansi: Gender, History, and Fable in India, “[s]ati was not a Hindu tradition expected of every widow, it had immense regional and class variance.” As a queen, it would have been acceptable that Lakshmi Bai serve as regent to the adopted heir.

Rani’s rebellion

Competing narratives have characterized Lakshmi Bai’s biography—she is a hero to the Indians and was a villain to the British (some called her the “Jezebel of India”). These interpretations stem mostly from the events of June 1857 when more than 60 English residents, mostly women and children, were massacred in Jhansi by rebel sepoys who had traveled south. In two letters to a British official after the mutineers moved on, Lakshmi Bai denied involvement in the attack, saying that the sepoys did not answer to her, and she hoped they would “go straight to hell for their deeds.” The East India Company refused to believe the rani had no hand in the tragedy. (Meet Zenobia, the rebel queen of Palmyra who took on Rome.)

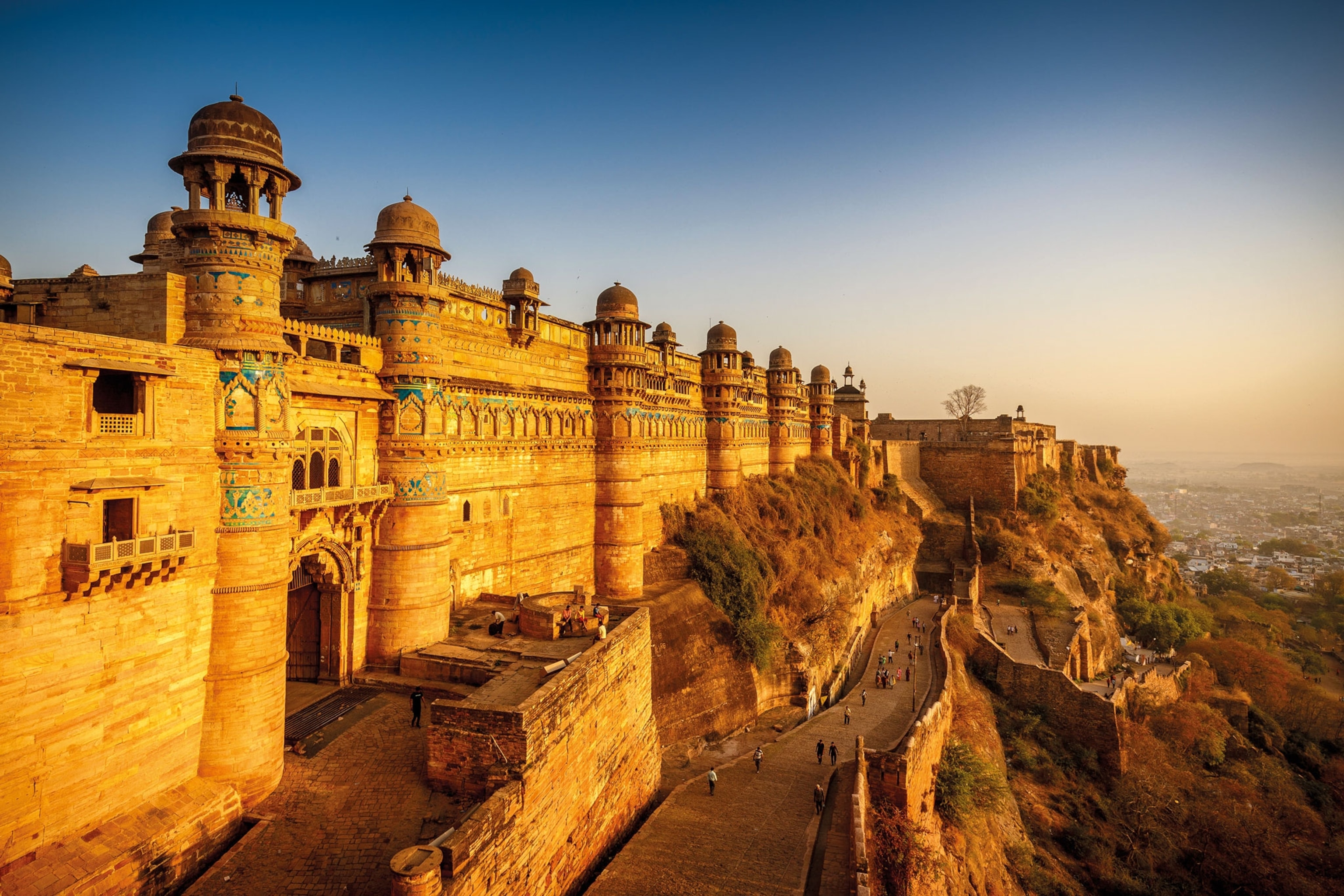

Lakshmi Bai’s hold on power in Jhansi lasted until March 1858, when company troops led by Gen. Hugh Rose laid siege to the fortress. The rani rallied her defenders to hold out against a relentless bombardment, returning fire with heavy guns of their own and rebuilding walls, but after two weeks the British broke through.

The rani escaped under the cover of darkness, accompanied by her guards and, it is said, her son strapped to her back. In early April, as the British troops moved in to take the city, one soldier records that he was told to “spare nobody over 16, except women of course.” The British troops duly behaved murderously in Jhansi, with the death toll reaching as many as 5,000 people.

Linking up with other rebel leaders, Lakshmi Bai occupied the town of Kalpi, but ultimately failed to hold it. Her forces then mounted a successful assault on the city-fortress of Gwalior. After this lone victory, she led her troops on a march east to confront a British counterattack led by General Rose. Here she met her end, and the rebels were defeated. (Discover Begum Samru, India's forgotten power broker who commanded armies.)

According to a report found among the papers of Lord Canning, India’s governor-general at the time, the rani, who “used to dress like a man (with a turban) and rode like one” was shot in the back by a trooper of the Eighth Hussars. When she turned to fire back, he ran her through with his sword and killed her. General Rose would later pay homage to his adversary, noting that “[t]he Indian Mutiny had produced but one man, and that man was a woman.”

Inspiration for India

The rani’s adopted son, Damodar Rao—whose right to the throne of Jhansi had fueled his mother’s decision to fight the British—fled with his guardians. In his memoir, Damodar Rao describes years of great suffering as he and his protectors struggled through a landscape of jungle and ravines. Some took pity on the fugitives; others refused them help for fear of reprisals from the British. Eventually Damodar Rao surrendered to the authorities, who granted him a small pension. He lived out his days in penury and died in obscurity. His descendants have never received government recognition as members of the rani of Jhansi’s family.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was the beginning of a much larger struggle that would last for nearly a century. In the early 1940s the Indian National Army took up the fight. Among its ranks was an all-female corps called the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, named in honor of Lakshmi Bai and composed of young women determined to fight for freedom. (Here's how Mahatma Gandhi changed political protest.)

After India achieved independence in 1947, Lakshmi Bai’s legacy continued to flourish. Indian poet Subhadra Kumari Chauhan penned “Jhansi Ki Rani,” a poem in Lakshmi Bai’s honor, which is taught to schoolchildren all over India to this day. Translated from Hindi, it features this refrain: “This story we heard from the mouths of Bundel bards / Like a man she fought, she was the Queen of Jhansi.”