Jane Austen never wed, but she knew how to play the marriage game

While the author stayed single, Austen used her keen powers of observation to fill her novels with juicy insights into how the gentry flirted, courted, and coupled in 19th-century England.

“We have now another girl, a present plaything for her sister Cassy and a future companion. She is to be Jenny, and it seems to me as if she would be as like Henry, as Cassy is to Neddy.” With these words, the Reverend George Austen announced the birth of his daughter Jane, the seventh of eight children (six boys, two girls) born to his wife, Cassandra Leigh. No one could have suspected that this baby, born in 1775 in Steventon, a small town in England, would become one of the most famous novelists of all time. She died at just 41 and now rests in Winchester Cathedral.

Jane Austen’s life was spent mainly in the domestic sphere, always living with immediate family, and never working outside the home. She lived in Steventon in Hampshire for 25 years (except for brief stints at girls’ schools), in the resort town of Bath, the port and naval station of Southampton, and finally Chawton. She lived through the American War of Independence, the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and much of George IV’s regency. She never left southern England, died in Winchester, and never married, though she had more than one proposal.

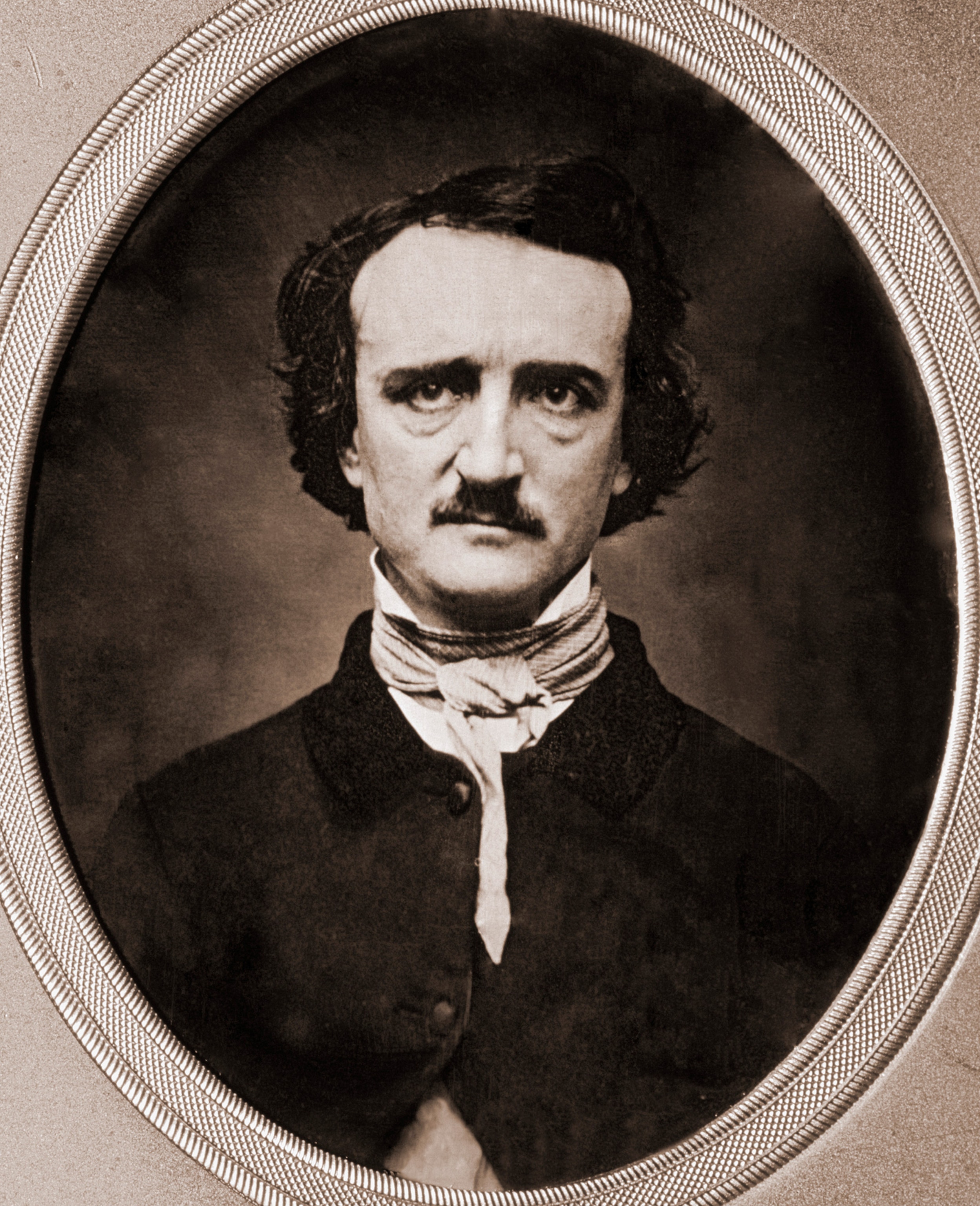

(Before writing "Little Women," Louisa May Alcott penned "blood and thunder.")

But through her acute powers of observation, Austen depicted English society of the period in delicious and often ironic detail. She focused on the dramas in genteel drawing rooms of the upper classes and members of the gentry in her six major novels. All of them place female characters center stage. With wit and keen insight, Austen highlights the enormous obstacles they faced in trying to secure even minimal independence.

Life in Regency England did not encourage freedom of expression, and penalties for speaking against society’s status quo were high. Women in particular lacked most legal protections, including owning property and making legal and financial decisions in their own names. In a uniquely insightful and subversive style, Austen’s novels address these and many other social and political issues: primogeniture, entailment, and inheritance; royalty, wealth, poverty, and social class; adultery and illegitimacy; colonialism and slavery; and equal rights.

Jane and her sister, Cassandra, received a brief formal education at boarding schools. In Austen’s time, the purpose of educating genteel young women was to raise their stock in the marriage market. A young woman was more likely to land a decent marriage proposal if she possessed accomplishments. Some young ladies were educated in girls’ schools, others at home with a governess. But most would learn to play a musical instrument; to draw, embroider, and dance; and to speak a polite smattering of French, considered a sophisticated language. Superficial studies in geography and history might be useful, too, but only as a way of enlivening conversation.

In her novel Emma, published in 1815, a year and a half before her death, Austen describes Mrs. Goddard’s school as “a real, honest, old-fashioned boarding school, where a reasonable quantity of accomplishments were sold at a reasonable price, and where girls might be sent to be out of the way, and scramble themselves into a little education, without any danger of coming back prodigies.” At 17 or 18, or sometimes earlier, the daughters of upper-middle-class families were launched into society and the marriage market. For daughters of the aristocracy and some other privileged families, this included being presented to a member of the royal family at the Court of St. James’s in London. For less well-connected young women, “coming out” would mean attending a private party or a local dance. Once “out,” a young woman would attend an array of social events: walks, balls, and tea parties, all with the ultimate goal of meeting an eligible gentleman willing to make a marriage proposal.

(This single working mom was Europe's first professional woman writer.)

How to have a ball

Inheritance issues

Such a proposal could be a lifeline for some women and their families. The fate of many was marked from birth by an inexorable law of inheritance. When the male head of household died, almost all his possessions were typically passed to his eldest son, through entailment. If he had only daughters, legal conditions often came into play. A man’s assets would skip over the family’s women, inherited by the next male in the familial line, which could leave the deceased’s immediate family with no income. In Pride and Prejudice the Bennet family’s estate is subject to such an entailment. When Mr. Bennet dies, Longbourn would pass not to his wife or five daughters, but to Mr. Collins, a distant cousin.

Often, women’s only share of the family fortune was their marriage dowry. So for many women, marriage was the only way to achieve any material stability. Charlotte Lucas in Pride and Prejudice openly admits her plight in a difficult conversation with her friend Elizabeth Bennet when they discuss Mr. Collins’s proposal: “I ask only a comfortable home; and, considering Mr. Collins’s character, connections, and situation in life, I am convinced that my chance of happiness with him is as fair as most people can boast on entering the marriage state.”

Clinching the marriage deal among the gentry involved a transaction between the two families. The groom was expected to have the means to support his new wife, while the bride had to contribute the dowry put aside for her by her family.

(How a teenage girl became the mother of horror.)

Lack of funds rather than changes in affection ended many relationships. In Austen’s Sense and Sensibility (1811)—the first of her novels published in her lifetime—Marianne Dashwood falls in love with a handsome gentleman, John Willoughby, and he with her. However, Marianne has only a modest dowry. Following the revelation of Willoughby’s involvement in a scandal, he is disinherited by his wealthy aunt, and ruthlessly abandons Marianne to marry a wealthy heiress.

Wealthy relations

Proper professions

Securing a marriage proposal from the heir to a large estate would have been the dream of many young women in Austen’s day. Such a match guaranteed economic and social position. Landing a member of the aristocracy, with a title, privileges, and possessions, was a bonus. Pride and Prejudice’s Fitzwilliam Darcy is perhaps the best known of all the eligible gentlemen in Austen’s novels. As the owner of an extensive Derbyshire family estate, his annual income is 10,000 pounds (equivalent to more than $1 million today).

While being the firstborn son usually meant inheriting the family estate, younger brothers needed to find themselves a profession. Manual trades were unthinkable for the upper classes and the gentry. Trade, though potentially lucrative, was seen as vulgar. A man might well become rich through it, but he would never be considered an equal by the members of the nobility. The only respectable career options for those who wanted to maintain social standing were the clergy, the law, or the armed forces.

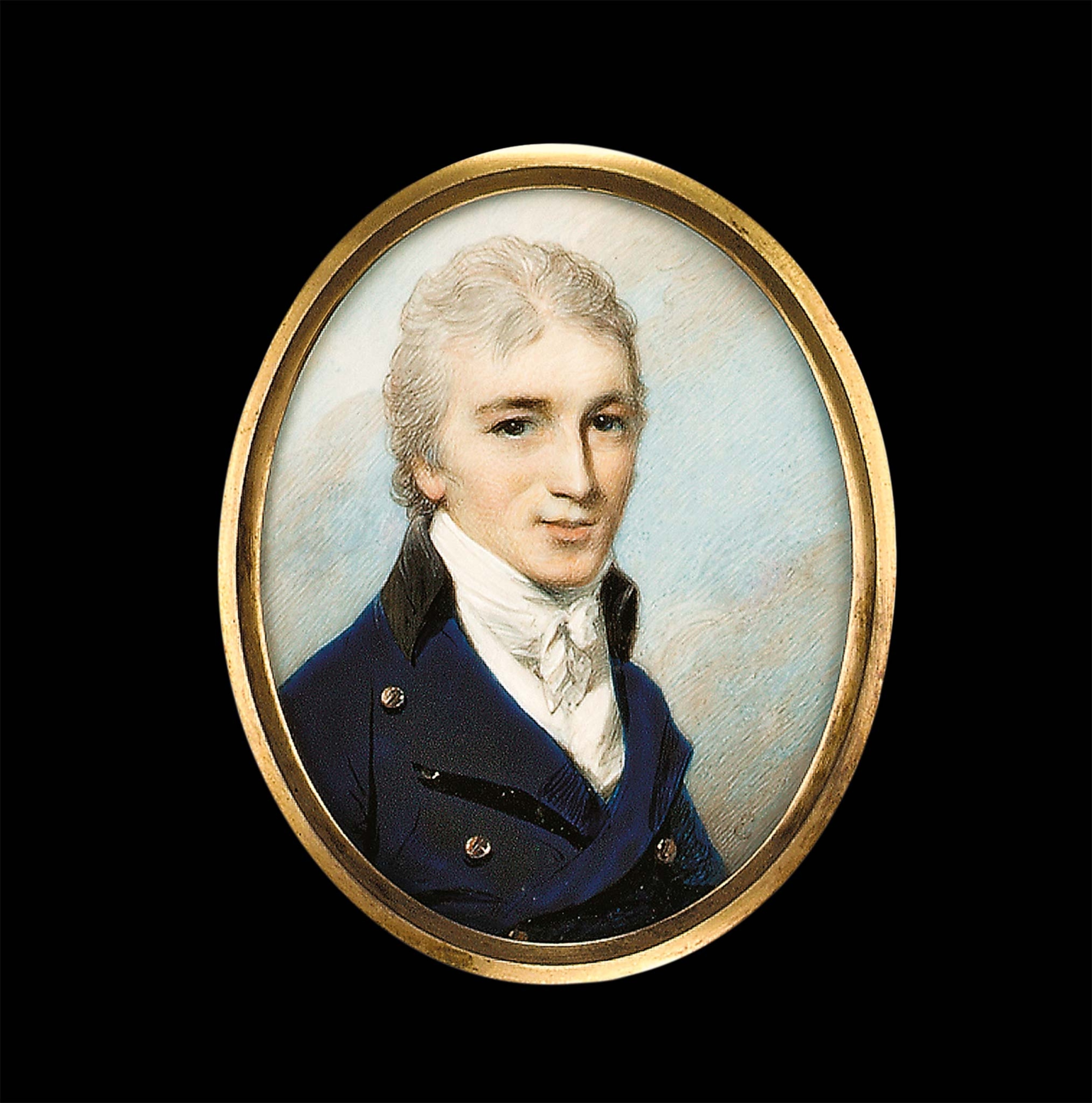

Traditionally, few who went into the military made a fortune that could compare with that of upper-class firstborn sons. But during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) some did get rich, especially Navy officers who took a share in bounty looted from the French. In Austen’s Persuasion her protagonist, Anne Elliot, accepts a marriage proposal from Frederick Wentworth, a low-ranking seaman. Anne’s associates force her to break off the engagement. Eight years later, Wentworth returns from war as a captain with a large fortune and finally marries Anne.

(Agatha Christie's adventurous "second act" plays out in Mesopotamia.)

Becoming a clergyman was another option for a second son. In Regency England Anglican clergy were held in high regard and moved freely between social classes. With the right connections, ideally a patron from the aristocracy’s upper echelons, a clergyman could obtain a parish or chaplaincy along with a home and a secure, if modest, income.

A room of her own

Yet some young women remained skeptical about ecclesiastical suitors. In Austen’s Mansfield Park (the third of Austen’s novels to be published in her lifetime, in 1814), Edmund Bertram, second son of a wealthy landowner, decides he will be ordained at 24 and run a parish on his father’s land. Edmund is in love with charismatic Mary Crawford, who is unimpressed: “So you are to be a clergyman, Mr. Bertram. This is rather a surprise to me,” she says. He replies, “Why should it surprise you? You must suppose me designed for some profession, and might perceive that I am neither a lawyer, nor a soldier, nor a sailor.” But Mary’s opinion is categorical: “Men love to distinguish themselves, and in either of the other lines distinction may be gained, but not in the church. A clergyman is nothing.”

Austen in Love

Given the transactional vision of marriage typical of the period, it is striking to some that in her novels and personal correspondence, Austen repeatedly defends marrying for love. “Oh, Lizzy! do anything rather than marry without affection,” Jane Bennet pleads with her sister Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice. In her own life, Austen espoused the same beliefs. She wrote to her niece Fanny: “Nothing can be compared to the misery of being bound without love— bound to one, and preferring another; that is a punishment which you do not deserve.” In fact, several of Austen’s protagonists do reject marriage proposals from wealthy gentlemen even though they are being offered a life of luxury and comfort.

Taking a look at Austen’s own life, it is tempting to see these instances as more than just romantic plot twists. She seems to have followed her own edict when she received a proposal of marriage from Harris Bigg-Wither, brother of a dear friend and heir to Manydown Manor. Although Austen initially accepted his proposal, she turned it down the next day. For an author often mischaracterized as writing Regency romances, Austen always had a clear-eyed view of what marriage entailed and what she wanted.

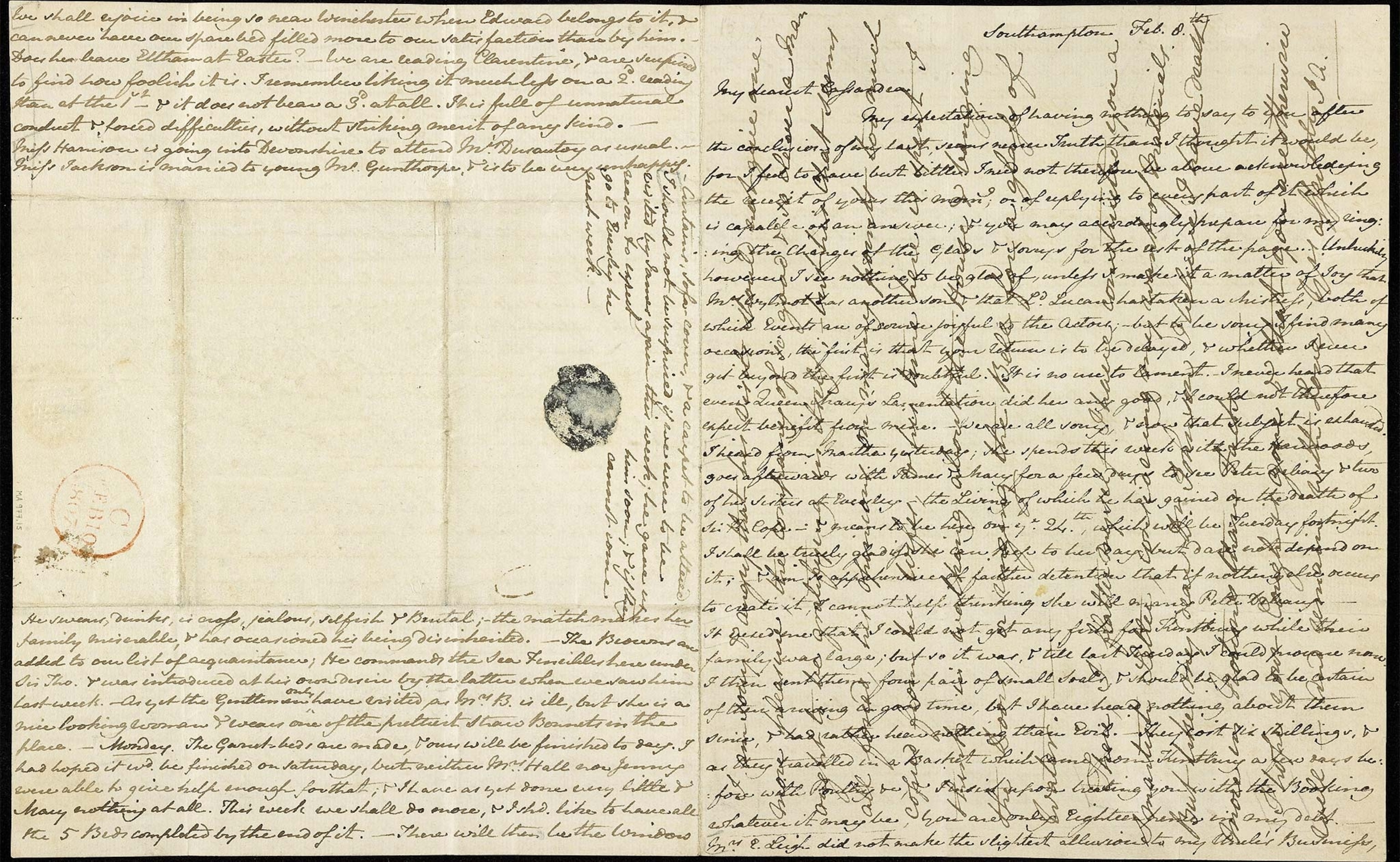

Austen and her sister remained unwed, a situation that she herself recognized as unenviable. As she wrote with her usual irony and wit in a letter to her niece Fanny: “Single Women have a dreadful propensity for being poor—which is one very strong argument in favour of Matrimony.” Professional opportunities for a single genteel woman were quite limited. Unless she had private means, through an inheritance or assistance from a family member, the most common field for such a woman to earn a living was either as a teacher in a girls’ school, or as a governess to gentry. This was Jane Fairfax’s situation in Austen’s Emma. A young woman of fine qualities but without money or connections, she is forced to accept a job as a governess, remain single, and move away from home.

Austen's affair

Emma also introduces the unfortunate Miss Bates, a mature single woman who cares for her elderly mother. They subsist on the meager interest from savings left by the late Mr. Bates. As a clergyman’s daughter, Miss Bates belongs to the gentry, but with such little income, she depends on her neighbors to lead a decent life. Mr. Knightley, one of her main benefactors, describes Miss Bates’s bleak situation in a pointed conversation with Emma: “She is poor; she has sunk from the comforts she was born to; and, if she live to old age, must probably sink more.”

(The history of book bans—and their changing targets—in the U.S.)

Transcending circumstance

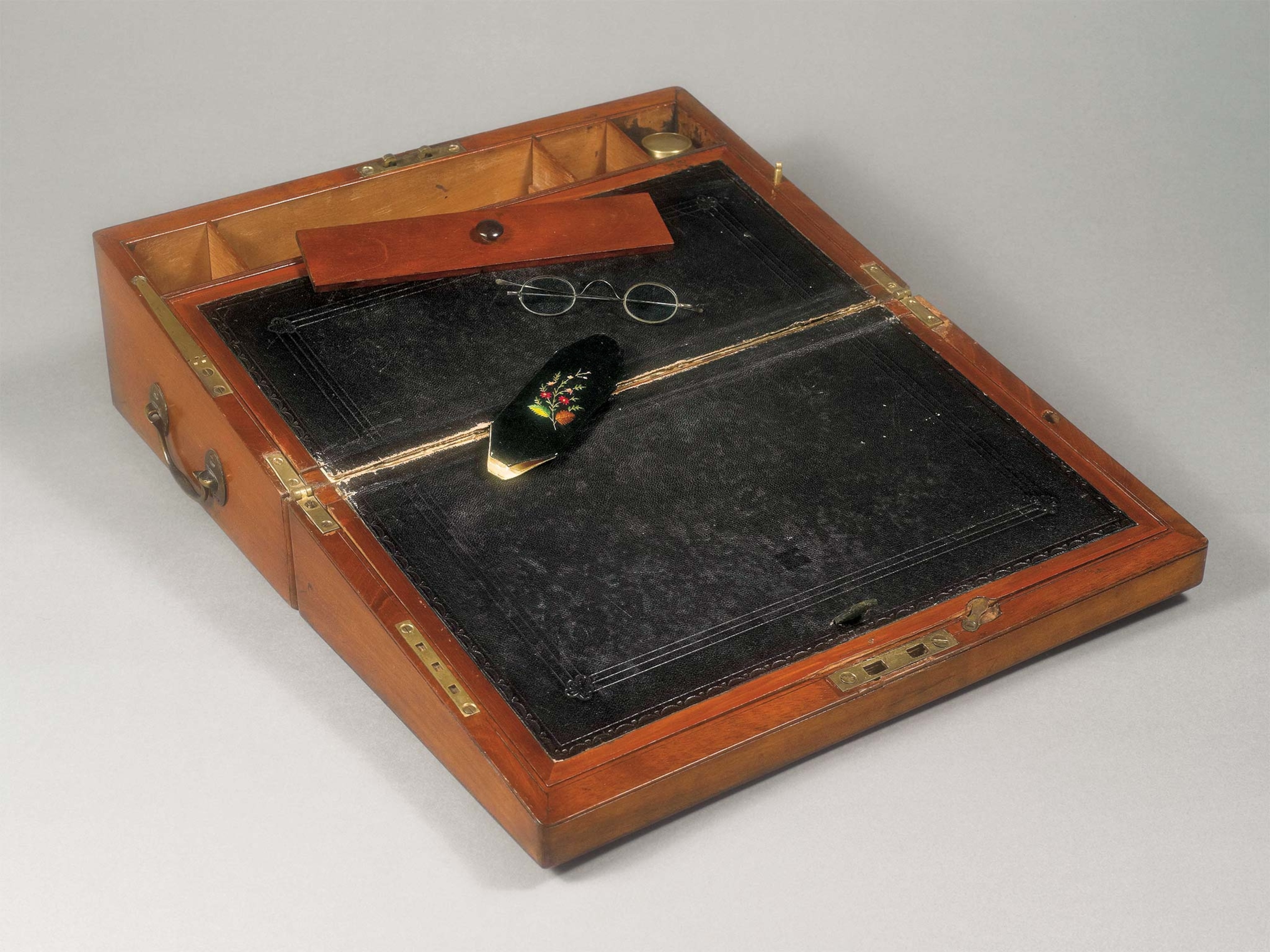

Jane Austen was a woman and a writer at a time when both circumstances posed challenges. Along with her mother and sister Cassandra, she knew hardship and financial dependency after her father’s death. They were forced to leave Steventon and were lacking a home of their own until brother Edward offered them Chawton Cottage.

However, rather than railing overtly against the social order and values of her time, Austen used keen observation to point out their shortcomings. She turned her curious, searching gaze on the people and situations around her, leavening her criticisms and raising social concerns subtly, with warmth, insight, and above all humor. What interested her most were the individuals she shares with her readers, reflecting the range of personalities and attitudes found in her social circle. But her timeless observations of human character and the way of the world transcend any limitations of her place and time, and have become classics.

Sir Walter Scott praised Austen’s “exquisite touch, which renders ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting, from the truth of the description and the sentiment.” He went on to lament for all her readers: “What a pity such a gifted creature died so early.”