Inside the booming business of cricket catching

Trappers of the hopping insects bring a key source of protein to Ugandan markets. But overharvesting and climate change could threaten this food of the future.

It’s a cold night, and strong winds are blowing atop a hill in southwest Uganda.

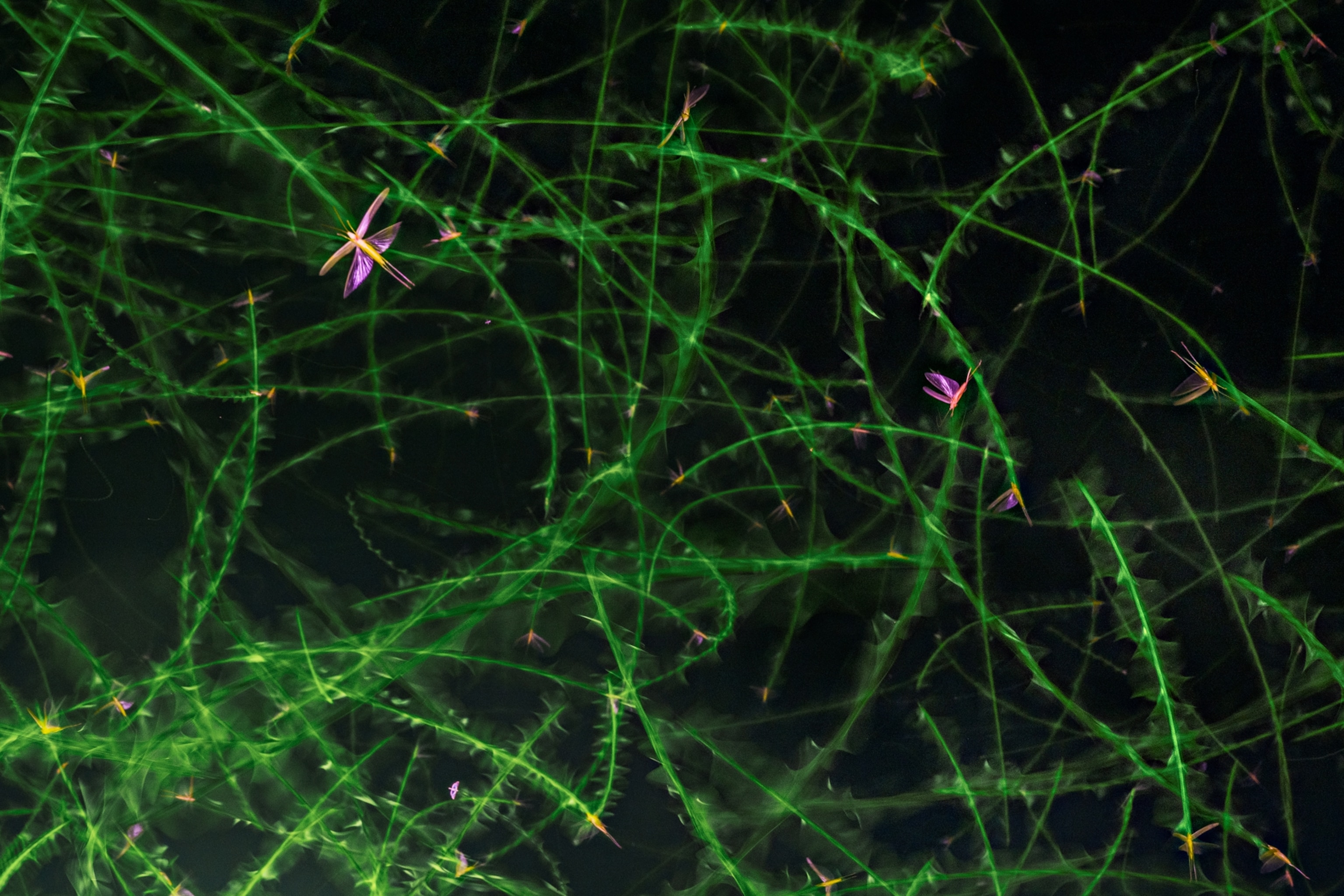

The wind rattles the four-by-eight-foot metal sheets that form the slanted walls of the giant insect trap. A diesel generator roars a few yards away, powering a 400-watt bulb at its center. The light is blinding to human eyes, but it’s a magnet for Ruspolia differens. In Uganda they’re commonly referred to as “grasshoppers” or nsenene (en-SAY-nay-nay),but they’re actually cone-headed bush crickets.

At the bottom of the metal sheets, dozens of drums stand empty. Soon, hopes Kiggundu Islam, chairman of the local bush cricket trappers association, they’ll be filled with millions of the nearly three-inch-long insects.

The “visitors,” as they’re called locally, come together to mate and feed in huge swarms after each rainy season in the autumn and spring, when hundreds of people across the country set aside their day jobs to come out and catch them. Salted and fried, the crickets are a delicacy in Uganda, sold for two dollars a bag at open-air markets, taxi parks, and roadsides. (“You see how you enjoy having a movie with popcorn? Me, it’s a movie with nsenene,” says one fan.)

It’s November 2020, and it should be the middle of the autumn harvest in Harugongo. Legend has it the insects come from the moon, and tonight it’s full. Yet “we’ve got nothing,” Islam says. “Where are they?”

Protein dense and full of iron, zinc, and other essential minerals, bush crickets, and edible insects in general, have been lauded by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization as a “food source of the future,” key for establishing food security, alleviating hunger, and preventing undernutrition. That’s important in countries such as Uganda, where nearly a third of children are stunted, and half of children under five and a third of women are anemic. (Here are 5 innovative foods you’ll be seeing more of soon.)

But what once was a small-scale and personal harvest in Uganda has become an increasingly commercialized undertaking, with giant hilltop and rooftop traps taking tons of the insects at a time to meet the growing demand. Meanwhile, decreasing catches suggest bush crickets are being overharvested, leading to pressure to make the collection more sustainable.

When Islam began collecting them in 2017, it was only for himself and his family. They collected the crickets that were attracted to their home by a security light.

But the growing market promised a nice income, and Islam soon set up two commercial traps. “The nsenene came in big numbers,” says Islam, a slim man with a deep voice. “We had a lot of customers who came for them.

“On a good [night] you can get as many as 400 bags,” each weighing up to 110 pounds, “which we then transport to Kampala and sell,” he says. But three days on the Harugongo hilltop have yielded nothing so far.

“The demand for this insect has escalated,” says Philip Nyeko, an entomologist in the Department of Forestry, Biodiversity, and Tourism at Makerere University in Kampala. “The supply, being seasonal, cannot now keep up.”

Nyeko leads a team of researchers developing a method for farmers to captive-breed the bush crickets. The goal is to take the pressure off wild populations, allow for a year-round supply of nsenene, and provide another source of income for farmers, whose crops are increasingly at risk from severe droughts and pests.

But until recently, not much was known about the biology, ecology, or life cycle of these insects. The scientists had to start from scratch.

“If you bring them from the wild, under what conditions do you keep them? Where do you keep them?” Nyeko says he wondered. What temperature do they prefer? What foods do they thrive on? Where will they lay their eggs?

On a sunny morning at Katwe, a market in Kampala, small wooden stalls line a muddy dirt road that leads to an open playing field. Next to the stalls are men and women seemingly sitting idle under large umbrellas.

Then a man appears on foot, carrying a plastic sack. It’s half-filled with bush crickets. The vendors snap awake and crowd around him. They’re pulling the bag from all sides, hollering over each other. How much? Are you bringing more? When?

The man is a bush cricket wholesaler, but he has little for them today. The half sack is bought by a middle-age man with a nearby stall. Everyone else slumps away disappointed, hoping to be able to afford the next sack—whenever it comes.

The problem is not just overharvesting, says Hajji Quraish Katongole, head of the Old Masaka Basenene Association Limited, the national trappers organization, which sets safety rules for collection and registers collectors. “God has blessed Uganda with fertile soil and favorable environment,” he says, but logging to clear land for sugarcane and oil palms has destroyed much bush cricket habitat. And climate change is making the rainy seasons unpredictable, affecting the crickets’ swarming patterns.

“If we just depend on the wild, it may not be sustainable” for the species’ future, says Geoffrey Malinga, a senior lecturer at Gulu University, which has partnered with Makerere University and the University of Copenhagen for the captive-breeding project’s upcoming field trials. Cone-headed bush crickets can’t be allowed to disappear—they’re a crucial protein source for some Ugandans, “especially for children who are poor and are not able to afford sources of proteins like meat,” Malinga says.

By 2019, after eight years of experiments, Nyeko and his collaborators cracked the code of keeping and breeding bush crickets. Wire-mesh and Plexiglas cages, a variety of grains to eat, and damp sand did the trick. Next: field tests. The pandemic delayed plans to roll out a pilot project with farmers in 2020, but now it’s set to start in early 2022. The researchers have selected 99 villages in the central Ugandan district of Mityana to participate, with the goal that it’ll catch on from there.

“The farmers we shall train shall then train other farmers,” Malinga says.

They also plan to test out a porridge-nsenene mix for schoolchildren.

On the hill in Harugongo, Islam is back. A mask, pants, and long sleeves protect him from the trap’s bright light—and the painful Nairobi flies. It’s a few days into the 2021 fall season, and he’s caught about three sacks’ worth—two fewer than this time the previous year. Like others, he took out loans to stay in business and worries how he’ll repay them. “You struggle for plan B now,” he says. “You will have to go and hunt somewhere else [for] money, not in grasshoppers.”

Halima Athumani is a Uganda-based journalist. This is her first story for the magazine. Jasper Doest focuses on stories that explore the relationship between the natural world and humankind.

This story appears in the March 2022 issue of National Geographic magazine.