As food allergies rise, new treatments are on the horizon

It’s an exciting time for the allergy field, experts say. Here’s what to know about what causes food allergies—and the new research that may help us cope with them.

Food allergies can be incredibly life-threatening: hives, vomiting, trouble breathing, and plummeting blood pressure are among some of the most severe reactions people can have to the wrong food. Depending on the individual, allergies can manifest rapidly and may require emergency medical attention to treat.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 8 percent of children have negative reactions to certain types of fare compared to around 6.2 percent of adults. But health experts are looking into ways to circumvent these sensitivities, or in some cases, prevent them altogether.

“There is certainly a rise in the amount of food allergy that is around now that we're diagnosing,” says Patricia Fulkerson, section chief of the Food Allergy Atopic Dermatitis and Allergic Mechanisms section of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). “Our allergies in general are just increasing overall worldwide.”

For years, standard advice followed that parents should avoid giving children foods that could trigger their allergy. Now, research has shown that exposing kids to allergens earlier reduces the risk of developing a future allergy. For those who have already developed food sensitivities, new immune therapies hope to eliminate dangerous reactions all together.

Here’s what experts have shared about the latest advances in food allergy research.

What is a food allergy?

It’s hard to identify the number of people with particular food allergies in part because there are many kinds of food sensitivities with symptoms that mimic an allergic reaction. For example, lactose intolerance can trigger stomach pain like an allergic reaction—but it is technically a digestive system issue, and not a milk allergy.

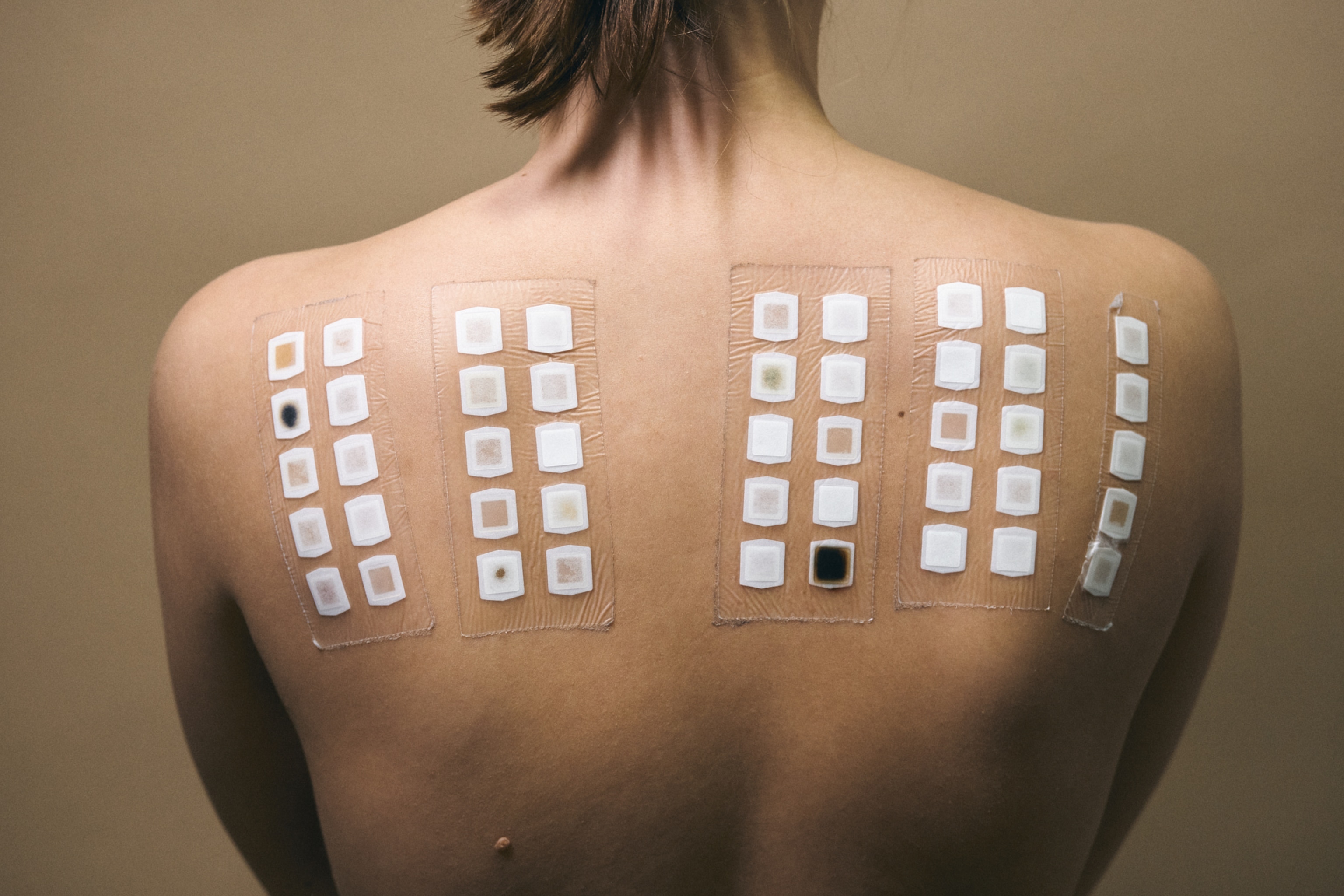

The best way to be sure a bad reaction to food is indeed an allergy is to get diagnosed by a doctor, says Ruchi S. Gupta, director at the Center for Food Allergy & Asthma Research (CFAAR) at Northwestern University’s School of Medicine. Once you know it is an allergy, she says, then you can develop a plan to treat it.

What makes a food allergy different from other sensitivities is an immune system response. In an allergic reaction, the body mistakenly sees a harmless foreign protein, such as a peanut protein, as dangerous. (Proteins that cause an allergic reaction are called allergens.) The body then produces an antibody called immunoglobulin E (IgE) to fight off the invader.

(How a tick bite can cause food allergies in humans.)

These antibodies bind to certain immune cells—eosinophils, mast cells, basophils—which when activated, release a chemical called histamine. This can produce an allergic reaction in any of the four major organ systems: the gut, skin, lungs, and heart. Symptoms include itching and rashes, constricted muscles in the lungs, and vomiting and diarrhea.

When more than one of the four systems are involved—for instance when a patient has symptoms in both the gut, like vomiting, and lungs, like difficulty breathing—it’s called anaphylaxis. In this event, the hormone epinephrine, delivered via an EpiPen injection, can be used to relax and open airway muscles for easier breathing.

“The respiratory and cardiac stuff is easily the most scary because that's really where you're talking about potentially life-threatening reactions,” says Dr. Edwin Kim, division chief of University of North Carolina Pediatric Allergy and Immunology and director at the university’s Food Allergy Initiative.

There are no mild or severe food allergies—just mild or severe reactions. Reactions can be somewhat unpredictable: an allergen that caused a mild reaction in the past could cause a more extreme reaction in the future, and vice versa.

Why are food allergies on the rise?

There are two causes for food allergies: genetics and environmental factors. Gupta says genetics alone cannot account for this rapid increase in allergies. What we do know, Kim says, is that kids are more likely to have allergies if both their parents experience immune dysregulation, whether seasonal allergies or eczema.

Meanwhile, two major theories examine the environmental factors leading to food allergies. The hygiene hypothesis posits that a society’s obsession with cleanliness reduces our early exposures to allergens—therefore making our immune systems more likely to overreact to common harmless proteins and trigger an allergic reaction.

(Why allergy season is about to get worse.)

In many parts of the world, kids also spend less time near dirt and livestock as in the past—which could explain why some studies have shown that urban areas have more food allergies than rural areas.

“We often talk about those first hundred days or first year of life and how important they are for infants’ bodies to see different things—that goes for playing in the dirt or exposed to different types of foods,” Gupta says. Fearing their infant might have allergies, parents have become overly cautious introducing foods to their babies, she adds.

But the hygiene hypothesis doesn’t completely address why allergies are on the rise. Researchers have found that high exposures to a certain food (like seafood in Asia) is sometimes associated with a higher prevalence of allergies to that food. This is where the dual exposure hypothesis comes in: this theory posits that the chance of developing a food allergy increases if an infant is exposed to traces of an allergen—by breathing it or touching it—before eating it.

Robert A. Wood, chief of the Eudowood Division of Allergy and Immunology in the Johns Hopkins Children's Center, gives the example of a parent rubbing lotion on their baby’s skin. If the parent has even a very small amount of peanut protein on their hands, the theory holds that it could make the child more likely to develop a peanut allergy later.

These two hypotheses are by far the most studied. Others include how changes in the way we cultivate and package food, as well as whether climate change may play a role.

New strides in allergy prevention

Oral immunotherapies, including exposing individuals to specific allergens at an early age, can be incredibly beneficial in the long term.

One of the best known examples of this was the LEAP study, wherein researchers found that giving children food with peanuts in it before their first birthday could drastically reduce their risk of developing a future peanut allergy. Their risk dropped by 81 percent by the time they turned 5, compared to children who had avoided peanuts.

This year, a recent follow-up of more than 500 of the original participants revealed that those early preventive measures worked even longer to protect these now-adolescents from developing food allergies. It didn’t matter how long they went without eating anything with peanut in it—that early exposure was so protective, the effect lasted for years, says Fulkerson. “It was very rewarding to see that it was so durable a response,” she says.

Preventing allergies from taking hold is sort of like the holy grail to researchers, Fulkerson says. But as allergies continue to propagate at an alarming rate, if some methods of prevention aren’t possible, newer treatments must be tried to retrain our bodies to be more accepting of what we know to be harmless nutrition.

For example, food allergies could once only be treated either by avoidance or by ingesting daily amounts of an allergen in gradually increasing doses to a maintenance amount.

Now, FDA-approved medicines help protect against the dangers of accidental exposure. One such example is the antibody drug omalizumab, (known widely under the brand name Xolair), which works by binding to immunoglobulin E in the blood and preventing it from arming the immune cells responsible for allergic reactions. In clinical trials, 68 percent of those with peanut allergies who received Xolair were able to eat peanut—but 17 percent had no significant change in their tolerance. Ergo, experts still warn allergy avoidance may be still necessary, despite treatment.

CRISPR advancements have also given scientists the ability to edit and delete allergen genes. This could one day lead to more applicable breakthroughs.

As research into allergy treatment progresses, coping with an allergy in the meantime can be stressful. But along with advice from a medical professional, learning what you can do to manage it could put some tasty treats safely back on the menu.

“It's really about what's comfortable for the family, what makes sense, so that's why getting the pediatrician involved is really the best approach,” says Fulkerson.