What scientists are learning about how to prevent allergies in kids

Research suggests that introducing kids to food allergens early in life can help—but that the same might not be true for other types of allergies. Here's what to know.

Almost 30 percent of children in the U.S have a diagnosed allergy, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, putting them at risk of symptoms ranging from hives and sneezing to life-threatening anaphylaxis.

Several large studies have established that introducing children to potential food allergens within the first year of life decreases their chances of developing an allergy. But how much of an allergen should you give a child and when? And what about other allergies, like seasonal allergies, pet allergies, and skin reactions—can those be prevented, too?

There’s still a lot to learn about how children develop allergies. We spoke to experts to find out what we do know and questions we still need to answer.

Introduce kids to food allergens early

A decade ago, doctors recommended delaying introduction to common food allergens for the first few years of life. That was until 2015, when the Learning about Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study provided strong evidence that introducing peanuts to children when they are roughly 4 months old can decrease the risk of peanut allergies. Since then, studies on early introduction of eggs, cow’s milk and multiple common allergens have shown similar results. Now, experts suggest introducing food allergens early in life, says Priya Katari, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Katari recommends introducing all common allergens—egg, milk, soy, wheat, peanut, tree nut, fish, shellfish, and sesame—to children at age roughly four to six months, or whenever the child can hold their head upright and chew and swallow food without spitting it up or choking.

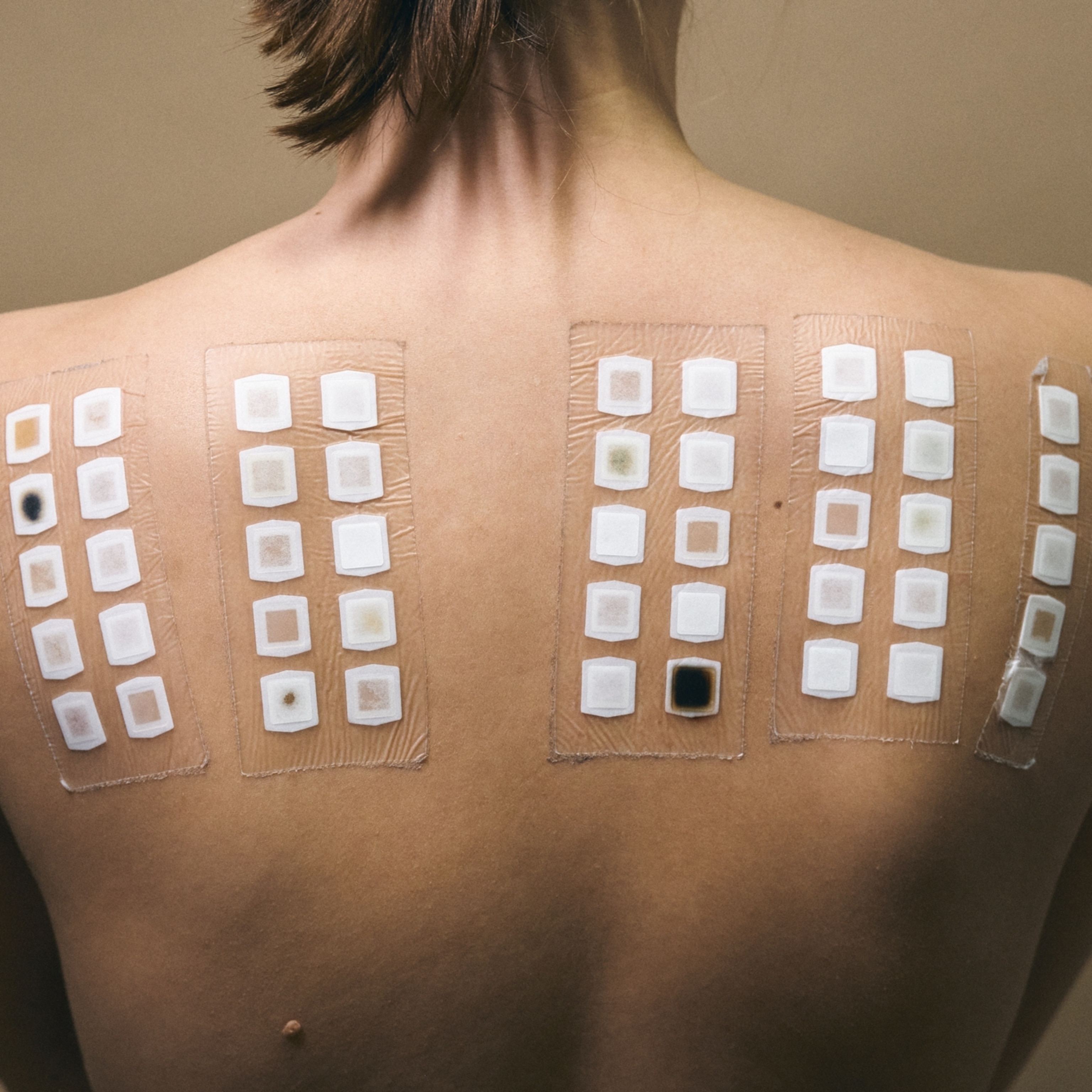

This goes for most children, even those with a family history of allergies. Two exceptions are children with severe eczema, who should be tested for allergies before introducing allergens through food, and children with a known egg allergy, who should be tested before introducing peanut butter.

Otherwise, the risk of a bad reaction, such as anaphylactic shock, after first introducing a food in children under one year old is rare, Katari says—but can happen at any age. Parents can start with just a bit of an allergen at a time—roughly one-quarter of a teaspoon of thinned peanut butter, for example—and monitor children for ten minutes before introducing a full serving—two teaspoons of peanut butter, or 2 grams of protein based on what’s on a nutrition label, is a reasonable goal, Katari says.

“I would say that whenever you introduce solid food, whatever foods your family eats go ahead and introduce them to your child,” says Martha Hartz, a pediatric allergist at the Mayo Clinic.

Once you introduce an allergen, it’s important to keep it in a child’s diet, Katari says. Peanut is the only food allergen that currently has guideline-based recommendations with regards to quantity and frequency—two teaspoons three times a week. But just a taste of an allergen likely won’t induce tolerance, experts agree. Don’t stress if it's less than exactly the recommended amount, just as long as children are regularly exposed to allergens. And parents don’t need to worry too much about keeping track of all of the foods you feed your child, Hartz says. Just make sure your child is eating a varied diet of fruits, vegetables, and protein.

That doesn’t mean everyone’s caught on, however. Hartz says that there are still some parents and practitioners who learned the old guidelines and are still employing them. “That’s why it’s still important to keep spreading awareness,” Katari says.

When introducing new foods, experts agree that it’s important to watch for signs of an allergic reaction at any age. For children of any age and adults, that includes hives, swelling, rash, redness, immediate vomiting or diarrhea, or trouble breathing, Katari says. For small children, behavioral changes might also be clues. Infants and toddlers may become more upset or withdrawn, especially if they can’t vocalize their discomfort yet. If children have had an allergic reaction to any allergen, their parents should talk to their pediatrician, Katari says.

What about pet allergies, seasonal allergies, and others?

For non-food allergens, the picture is more complex. Whether people develop allergies depends on a number of factors, including their genetics, immune system, and their environment, says Asriani Chiu, a pediatric allergist at the Children's Wisconsin and the Medical College of Wisconsin. “It’s really hard to tease out what causes an allergy,” she says.

“The biggest risk factor is genetics and family history,” says Rita Kachru, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at UCLA. Any type of allergy in the family can increase the risk of developing allergies of any kind, she says. In addition to genetics, allergies tend to be a result of consistent exposure over time, explains Chiu. Pollen allergies, for example, typically don’t manifest until after age 4 or 5, after children have been exposed to high amounts of pollen for multiple seasons, Kachru says.

In general, early exposure to non-food allergens likely helps prevent allergies, Kachru says. For example, a few studies have suggested that introduction to pet dander during the first year of life can decrease the risk of developing any allergy.

But this comes with some caveats. For example, studies also show that children who grow up in households with pests like cockroaches and mice are more likely to develop asthma. In another example, babies that need medical procedures early in life are more likely to develop allergies to latex. Some studies on seasonal allergies show that pollen exposure during the first year of life can increase the risk of pollen allergy. So when is early in life exposure protective, and when is it not?

Unanswered questions about how allergies develop

One theory is dual-exposure, which posits that the way an allergen is first introduced matters. Exposure to allergens, like peanut dust, through broken skin or an inflamed airway can lead to an allergic reaction, Katari says. However, eating a potential allergen “tells the immune system, ‘this is something I’m supposed to eat,’” says Hartz.

The same goes for other allergies: if an allergen comes into the body through the skin, for example, it could trigger an inflammatory response that leads to an allergy, Kachru says. “I can’t emphasize enough that it’s important to try and take care of the skin, in particular, which is the largest organ during infancy,” says Kachru. It’s also why if your child has eczema, which causes breaks in the skin, it’s important to develop a skin regimen that can keep inflammation under control, Kachru says.

Generally, if the body’s barriers to outside toxins (the skin, respiratory tract, and gut) are kept healthy, the immune system might react better to allergens. Things like cigarette smoke that can affect these barriers should be kept away from kids, says Kachru.

Studies do show, however, that there are some things that can help decrease children's allergy risk, Chiu says. Some studies show that breastfeeding can decrease allergy risk. In addition, children that are delivered vaginally, as opposed to those delivered via C-section, have a lower risk of developing allergies, Chiu says. That might be because breastfeeding and vaginal delivery can increase the diversity of beneficial bacteria in a child’s intestinal tract, which studies show is correlated with decreased allergy risk.

Given that it’s difficult to untangle all of the factors that might cause allergy, doctors don’t have clear guidelines as to when or how to expose a child to non-food allergens. Partly, that’s because it's hard to control how and when children are exposed to allergens in their environment, says Chiu, especially things like pollen or dust. In addition, babies are hard test subjects to recruit, she says, as parents are unlikely to want to subject their otherwise healthy babies to medicine they might not need yet.

Scientists are learning more about the skin, gut, and respiratory systems, all of which contain immune cells that play an important role in the body’s response to outside toxins, Kachru says. For the skin, that means finding out the genetic and environmental factors that cause harmful inflammation. For the gut and respiratory system, that means figuring out what role the microbiome might play in allergy development, Kachru says. “We need inflammation. But how do we prevent it from reacting to things it shouldn't be reacting to?”