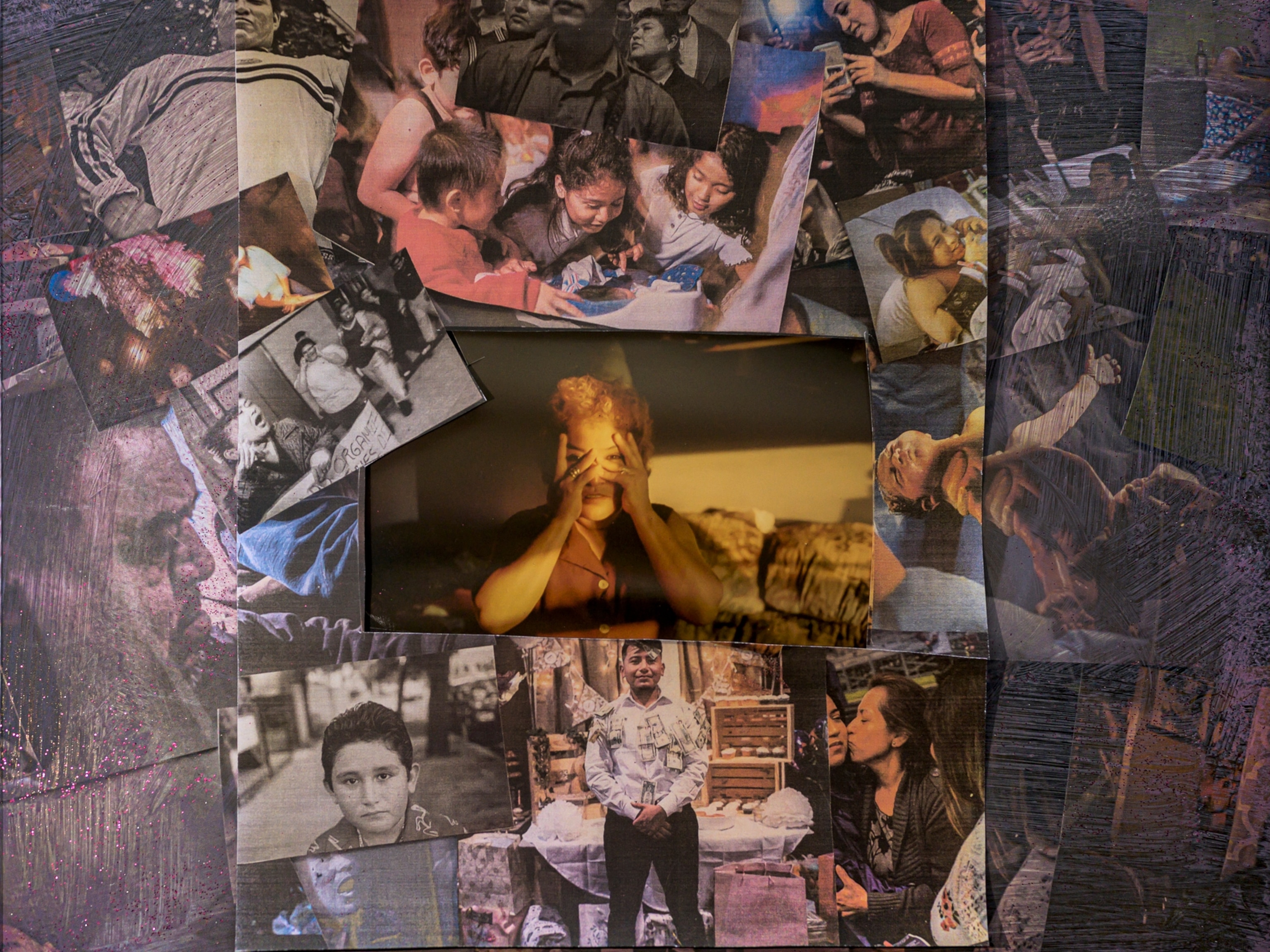

Fairy tales can come true, but sometimes it takes a few decades.

As a city kid, Elena Anosova heard seemingly tall tales of a village visited by elk and wolves, of a vast forest, impassable roads, and an environment both bitter and beloved. As an adult, the visual artist, now 34, finally visited the settlement founded more than 300 years ago by her ancestors. They were hunters, swept up in the waves of Russians who ventured east to Siberia in search of fur and never left. Anosova’s father was born there, and most of the 120 or so people who call the place home—and don’t want outsiders to know its name or location—fall comfortably into the category of family.

In the native Tungus (or Evenki) language, the settlement’s name translates roughly to “Island.” That’s a physical representation of what lies at the heart of Anosova’s work: the exploration of isolation and boundaries. To reach this dreamy, landlocked “island” by jeep, there is the winter road that for a time freezes over the swampy, subarctic taiga. The fastest approach is by helicopter, which flies twice a month from the town of Kirensk, 200 miles away. If the chopper is full, it means two more weeks waiting to get in, or out.

Once in, Anosova has discovered much to do and little rush to leave. There are wild horses to wrangle when it’s too warm to hunt on snowmobiles. There are crops to grow in oven-warmed greenhouses and preserve for winter. Cash is rarely necessary, except for trips to the city financed by the sale of sable fur. After visits to the village, city life feels different. “It’s difficult,” says Anosova, “because you need silence.”

Even the cold becomes something to long for. Temperatures in June can dip below freezing. Anosova keeps an image on her iPhone of the reading one recent January morning: minus 53°C (-63°F).

One photograph included in this story shows a man with his face awash in snow. To Anosova, it speaks of how those in the village “are at once overwhelmed and at one with the elements.”