What’s it like to be an immigrant in America? Here’s one family’s story.

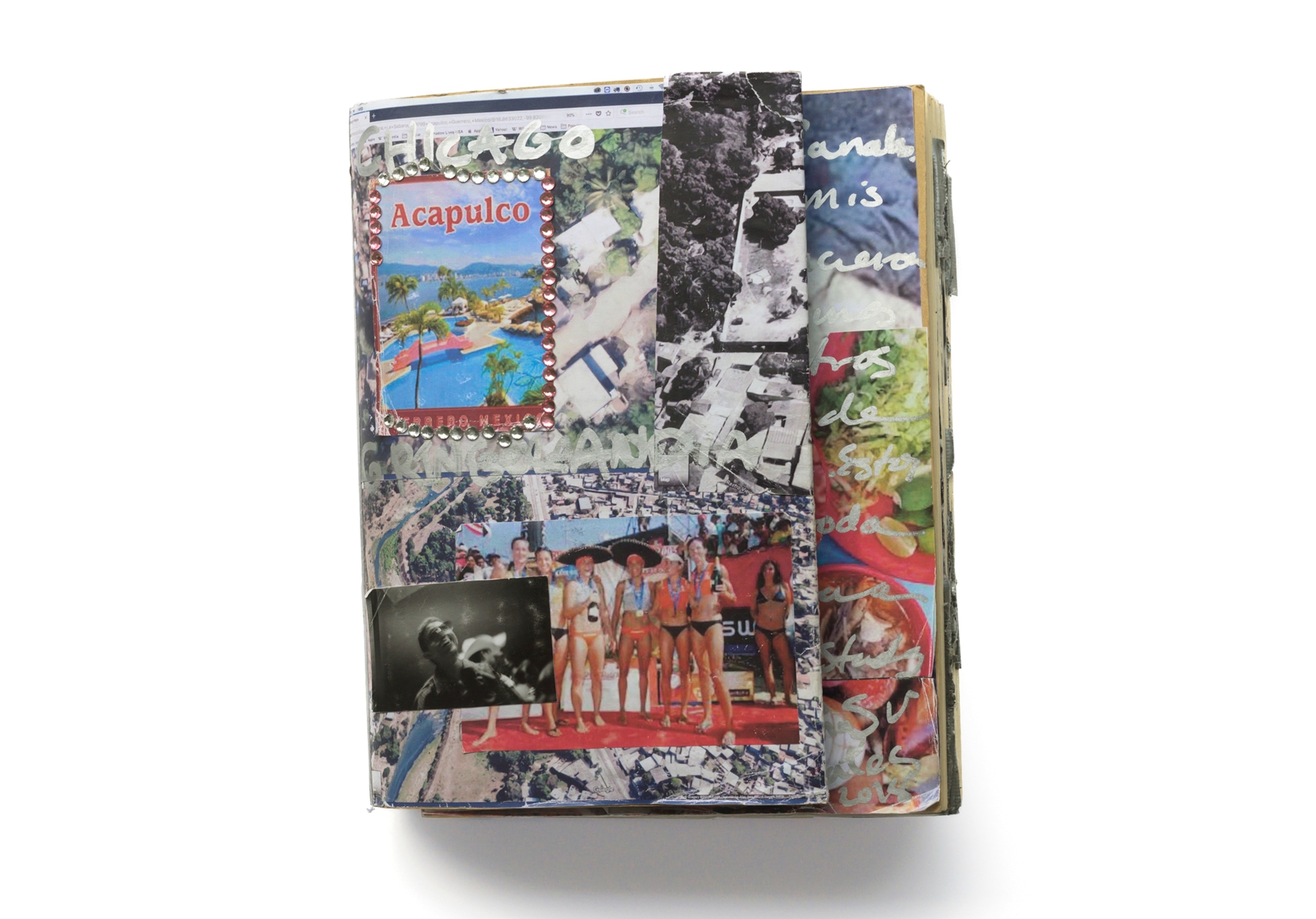

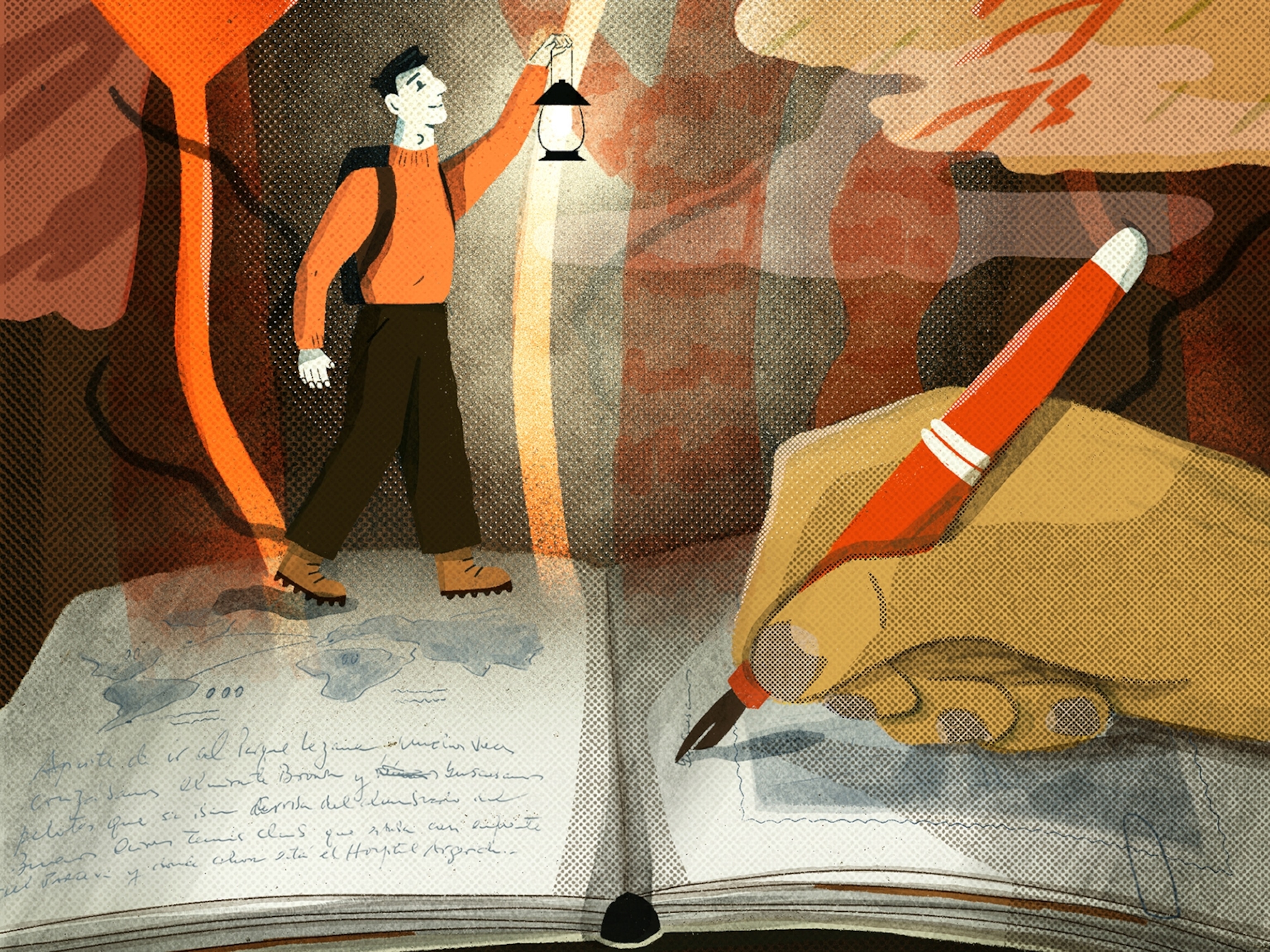

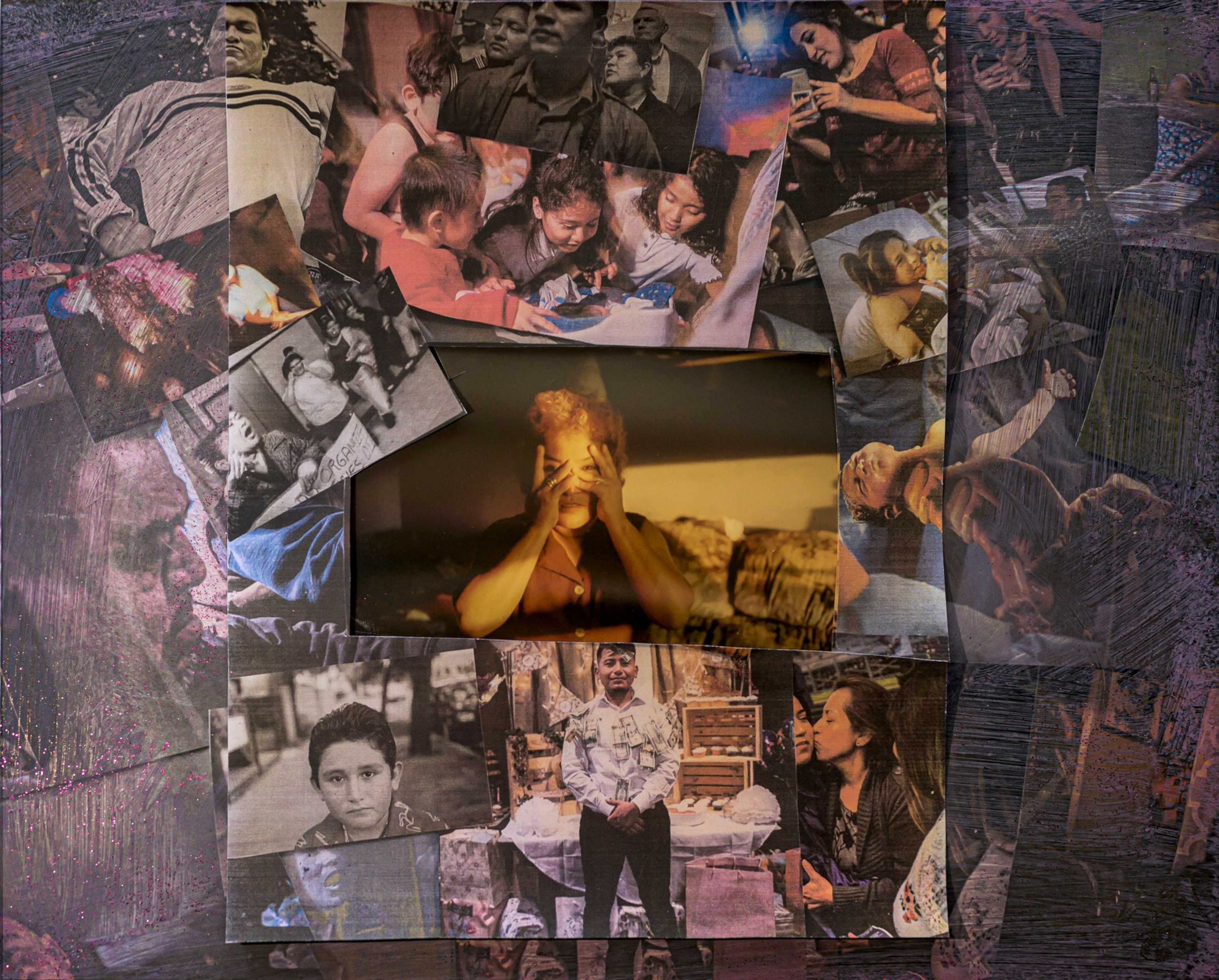

In 2000, photographer Jon Lowenstein met a Mexican transplant named Guadalupe on the South Side of Chicago. He’s been documenting her family’s American experience ever since.

It’s an American dream: These immigrants traveled across the continent and settled on the prairies. They prospered from working hard seven days a week and came to live in this ranch house west of Chicago.

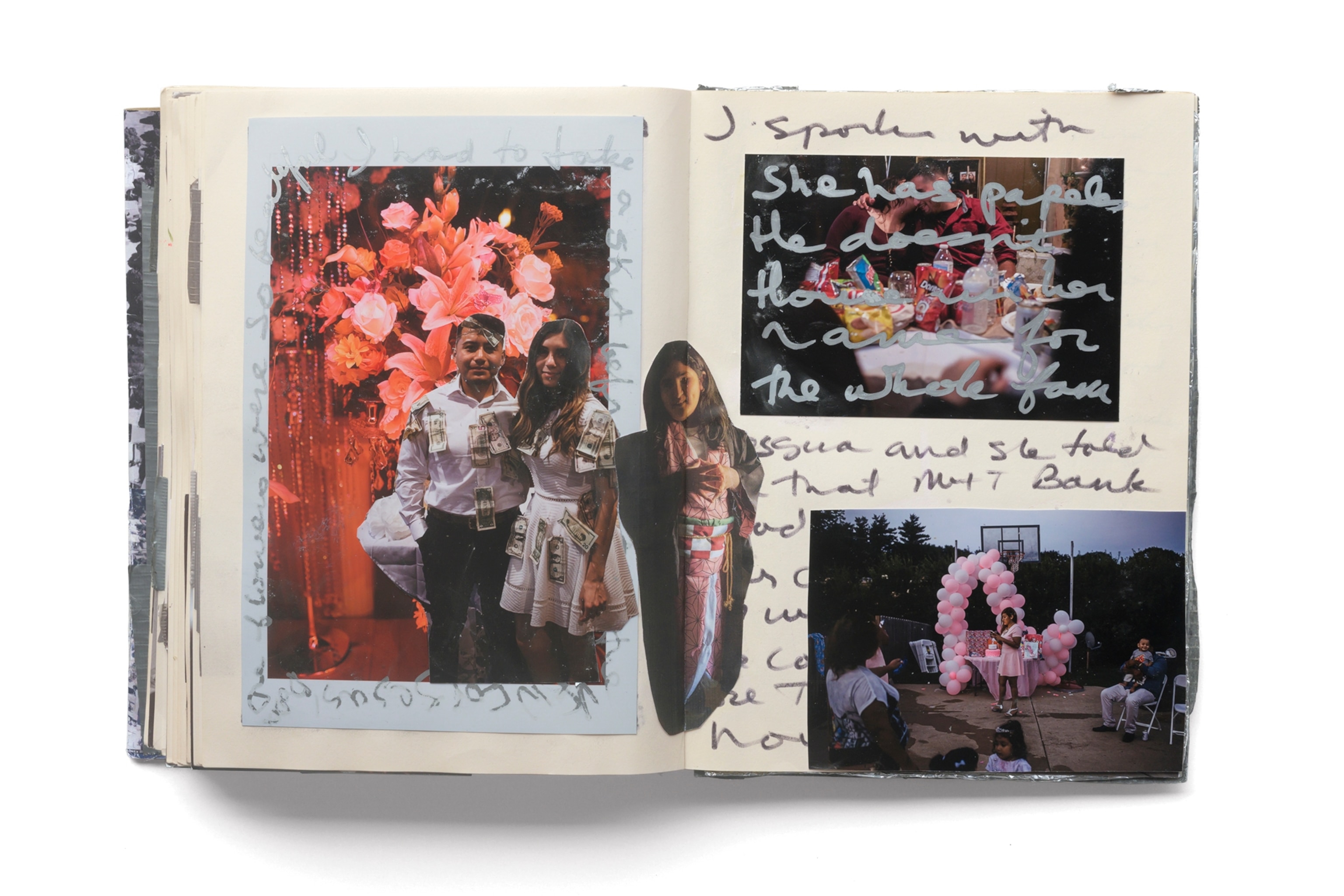

Today’s the birthday party for one of the moms. Two cakes, Mylar balloons, women in the kitchen, and the men still at work. Shiny cardboard letters spell out “Happy Birthday” on the living room wall. Children and grandchildren and nieces and nephews run the hallway and jump on the couches. The laughter spills outdoors.

This home on the Illinois prairie sits on the communal land of several nations. Ojibwa, Potawatomi, and Odawa families have roots here. Long ago the county two-lane might have been a wagon path, a dirt trail that hosted pilgrims and vagabonds heading west.

Perhaps they were escaping the mosquito-plagued marshlands of the Chicago lakeshore, a place whose name in the language of the Indigenous Miami-Illinois refers to an odorous wild garlic plant. Those who stopped here knew a good thing when they saw it.

Out there, across the road, a sea of cornstalks waves beneath a setting orange sun. The single streetlight on its tall stanchion comes to life and makes the nearest corn glow. Afternoon crows fly to the autumn trees and nearby silos and barns. Cows in the distance low mournfully. Dogs bark.

Off to the side of the house, machines for working the land rest on the grass. The backyard, hidden by a tall suburban fence, holds a pool and a compact playground, but nobody dares enter because the watchdog bites everybody who comes through the gate. Except for the visiting grandmother, who has the dog-whispering mojo—and the stern demeanor of an empress.

Inside the house, there’s always coffee ready for whatever traveler or laborer comes through the door, which never seems to be locked. In the kitchen, Doña Rosa cooks for her daughter Gabriela (“Gaby”) and Gaby’s husband, Salvador (“Chava”). Chava is still at work, leading his crew of landscapers through their appointments for fall cleanups. Doña Rosa has traveled by plane from Acapulco for Gaby’s birthday party.

As more and more people arrive for the celebration, the driveway fills with pickup trucks and minivans. Photographer Jon Lowenstein leads the way into the house. I feel uneasy, invading their celebration day, but Lowenstein is an unstoppable force and seems to be a de facto member of the family.

“Hola, Jon,” voices call from the kitchen. He has been photographing the family for 20 years, attending births and parties and tragedies with them for so long they don’t even notice his restless camera, or its hunger.

The focus of consternation at the moment is me. This is a private day, and they don’t know what my agenda might be. A writer? A writer of what? How can they know I want to simply bask—to go home to a house that no longer exists, to a language I seldom hear? Not Spanish, but small-town Spanish. Rancho and pueblo and garden Spanish.

The delicious steam in the kitchen, the scent of Mexican rice and refried beans, takes me back to 1963, to my godmother’s kitchen where no one ever spoke English. Though they tried, launching American phrases like “How are you?”—which always came out as “Fa-va ju?”

The women in the kitchen are welcoming, of course. Perhaps no one is as polite and generous as working-class people from villages in the heartland of Mexico. We are invited to sit. Bottles of the soft drink Squirt and glasses of water appear as if by magic.

“El Esqueert es muy bueno.”

“Sí, sí,” I enthuse.

Coffee immediately lands before us. Bottles of water crowd out the glasses, because they’re more special than tap water. Fruit juice. And an order: “You must eat.”

When I introduce myself in Spanish, the household unfolds, all its petals open to the sun.

“¿Hablas español como un mexicano?” (“You speak Spanish like a Mexican?”)

“Soy un mexicano.” (“I am a Mexican.”)

Handshakes are out of the question now. It’s all hugs and laughter. I wish Gaby a happy birthday. She pats my back, tightens her apron, and gets back to work. Over her shoulder, she says, “Sit.”

Doña Rosa suddenly drops her guard and moves her meal-construction project to the table where I’m sitting and sets up shop beside me. Thus, she announces her blessing.

A pan holds marinated meat, redolent of the sauce and herbs it’s basking in. It looks as rich as chocolate. Doña Rosa moves fast, her hands doing fascinating culinary origami. She’s preparing a traditional meal from her home state of Guerrero, a meal as ancient as the Chichimec tribe and possibly never seen in this part of Illinois. The closest one could get to describing it would be tamales. But only if one were to toss away the masa and the corn husks.

She wraps the marinated meat in banana leaves, then binds the tight packages in aluminum foil (a nod to modernity) and places them in steamers. Her eyes seem calibrated. She pulls the exact size of meat for the banana leaf set before her. These packets are piled atop cauldrons of boiling water on shiny grates. The aroma inhabits the space with its ancient incense.

Banana leaves keep the flavor in, Doña Rosa says.“Y la humedad. La carne sale tierna.” (She is proud of the tenderness of her dish.) “You need the good, strong flavor. It soaks into the meat, and my sauce can seep into the carne too. But nobody here can make it. You don’t have banana trees here.”

We ponder how sad this is as Gaby brings more coffee and I feel embarrassed that she’s tending to me. Lowenstein has vanished. I’m on my own.

“I brought the leaves with me,” Doña Rosa explains. “The airline didn’t think anything of it.” She shrugs. “I suppose I don’t look like a bad guy,” she says, giving me the side-eye. The thought of Doña Rosa being an outlaw drug smuggler makes Gaby laugh as she chops cilantro and onions behind the veil of steam.

“Gracias a Diós,” she sighs, her regular praise of the Lord. (Later in the night, she will unleash deeply satisfying strings of obscenities directed at a bad dog. My love grows deeper.)

Lowenstein reappears from some clandestine mission down the long hall. He takes pictures of Gaby’s hands, of the leaves, of the pots, of passing kids, of the vicious little dog come from no-one-knows-whence that has begun a military assault on the ankles of anyone who is not a child.

“Ay, que Jon,” Doña Rosa says, ignoring the persistent photographer while shaking her head in the slightly fierce way of a Mexican grandmother who hides her delight. “Es tremendo.” (“He’s something else.”)

Gaby works diligently in and around her mother as nieces and daughters flow through the kitchen and up and down the halls, all of them on hilarious intrigues. One wall is festooned with balloons and crepe.

Doña Rosa approves of my presence enough to try to teach me how to wrap the meat like a good citizen of the state of Guerrero. Which, she is proud to remind me, stands for “warrior.”

Although everybody is watchful—Chava the son-in-law is about to arrive—the strength of the Mexican family holds fast through its women. Elders are the current that carries history and legend and tradition to these distant riverbanks of life. The women let the men strut and rule, but they know all the secrets and arrange for the stage to allow the patriarchs’ displays.

When I introduce myself in Spanish, the household unfolds, all its petals open to the sun. Handshakes are out of the question now. It’s all hugs and laughter.

Gaby keeps offering me food. I try to avoid being a burden, but the women are offended. They can’t believe I don’t want rice and beans or fresh tortillas. I’m embarrassed to be served or fussed over.

In the living room, the TV is always on, and an army of small kids gathers on the couches and ottomans or suddenly barrels through the thickening forest of adults to charge up and down the halls. Little polyglot girls hold up stuffed animals and make announcements in their indecipherable inner languages. I notice that the dominant tones and words from English are already crowding out the Spanish music among the younger generation. Several of the young ones seem unable to speak Spanish, or perhaps they don’t want to.

“Todo cambia,” Doña Rosa says. (“Everything changes.”) Note to readers: Every Mexican grandmother is a philosopher.

The teens and young adults enjoy the dark living room and whisper secrets as the kids laugh at the shenanigans of an old SpongeBob cartoon. Elizabeth and Betza have great plans for their future lives. Somebody’s pregnant—I think her husband is with her. The young women are dressed to kill.

Suddenly, here comes Chava, the master of the house. The kids part. He kisses his wife, nods at Lowenstein, and turns a skeptical eye on me.

“Es escritor,” Lowenstein explains. A writer.

“What do you write?” Chava asks, sitting down at the head of the table.

“Everything. Books.”

“Books. About what?”

This feels like a test from Monty Python and the Holy Grail: If I answer incorrectly, I might fly out through the roof. But Gaby intervenes with tactically delivered food, steaming gorgeously before Chava.

“Gracias.”

He looks around to see if Lowenstein is going to torment him as he eats. It’s evident right away that he’s not all that comfortable being photographed. He still seems bemused by my place at his table. He shakes my hand. “You look like an American,” he says. He tests me on my Spanish prowess, a subtle entrance exam. He quickly relaxes.

This universal test is simple: Either you pass or you do not. It isn’t even what you say; it’s the way you say it. It’s musical, and it has an element of ballet. You can’t do New York gestures; you have to do Mexican gestures. If you have to ask, you’ve already failed the exam.

The strength of the Mexican family holds fast through its women. Elders are the current that carries history and legend and tradition to these distant riverbanks of life.

His handsome son Chava Jr. appears from down the hall. Chava and Chava sit together and stare at me.

“Aren’t you eating?” Chava Número Uno asks.

“Why isn’t he eating?” Chava Número Dos asks.

“No sé.” (“I don’t know.”) Chava One looks into the kitchen at Gaby and with his eyebrows asks what’s the problem.

Gaby comes to the table. “Don’t you like my cooking?”

“I offered him rice,” her daughter calls. “And he refused.”

“You don’t like rice?” Chava One asks.

“I love rice.”

“Why don’t you like rice?” Chava Two demands.

“I was trying to not be a bother.”

“Bring him rice,” Chava One orders.

Gaby puts a plate of rice in front of me.

“Just rice? What kind of meal is that? Don’t you like beans?” Chava One asks.

“Why don’t you like beans?” Chava Two adds.

“I thought you were Mexican,” Chava One adds.

“I am,” I sputter. “I do!”

“Bring him beans, then.” They add beans to my plate.

“Why are you eating that with a fork? Don’t you like tortillas?”

Chava Two holds his tortilla in his hand and looks at me with bewilderment. Chava One flips the cloth back on the basket, revealing a stack of hot corn tortillas. I take one.

“Mmmm!” I overact. “¡Maíz!”

Doña Rosa comments, in passing, “He doesn’t seem to like the meat I made.”

Where is Lowenstein?

Meat descends from above and behind like a drooling UFO. Now my plate is full of food. A monument of steamed-banana-leaf-meat extravaganza in a valley of rice and frijoles.

Chava One says, “What’s wrong? Don’t you like the salsa we eat?”

One of the men gradually collecting at the dining room table tells me: “Spanish, it’s like a vacation, isn’t it? Like a visit with our mothers and fathers.” The women of the family continue serving the table with no rest, and they scold anyone who’s not eating their food. Music plays. Earlier in the day, when the women in the kitchen were in charge, it was traditional Mexican music. Now that the kids are filling the living room and spilling down the hall into the mysterious rooms back there, it becomes dance music and hip-hop and Bad Bunny, the Puerto Rican rapper.

Lowenstein, the “terrorist with a camera,” is dancing up and down the hall. Every now and then someone shuffles along with him, but often he is dancing only with his camera. Clicking from the hip, from the shoulder, over his shoulder, occasionally carefully aimed. Interpretive camera dance. Shooting by instinct. The family doesn’t see him. He has become one of their tribe. But I notice that none of them call him “Juan.”

Gaby, the birthday celebrant, says, “Poor Jon. He shoots thousands of pictures. Aren’t rolls of film expensive? We must have cost him a fortune.” She hasn’t quite processed his explanations of the digital era. “Oh well. I need a shower,” she adds. “I need to fix myself for the party. I need to be glamorous.”

Doña Rosa says, “Jon keeps taking pictures of me in a smock and apron. We both need to primp.”

He snaps a birthday portrait of the three of us in the kitchen, and I suddenly feel like I’m Bigfoot towering over two diminutive and very serious campers.

After Doña Rosa and Gaby leave to shower and dress for the evening festivities, my new friend Zenon sits with me. It’s a miracle of Spanish that as soon as you share the language, you are brothers. Unless you seem to not like the beans.

Zenon is a fountain of kind energy. He notices my Alaska baseball cap. “You have been to Alaska?” he asks. I nod. “Is it attached to America?” Yes. “Is it far?” Oh yes. “Mountains?” Many mountains.

He seems wistful. “I want to see mountains. But I will not find them in Illinois.” No. “I went to the west of Illinois. They had some little mountains. But I didn’t like the river.” The Mississippi? “Sí. It was brown. That big river, it was dirty.” I blurt in my joy: It flows all the way to Louisiana! “Is that in the United States? Anyway, I went to Wisconsin for work. But no mountains there either. Maybe Indiana? They have casinos in Indiana,” he says, brightening.

We share a moment of quiet in the growing storm of delight. The far end of the family room is full now with women and children. The living room TV still blares cartoons, but now the teens and twentysomethings have filled the space. The dining table is full of boisterous men. The kitchen is full of women. One of the partyers at the table is telling us why he no longer drinks alcohol.

“I got drunk at a party and chased people around with two machetes!” For some reason, this makes us all laugh so hard tears spill from my eyes. Perhaps it is the reenactment. We pound the table. We give him comradely abrazos. “They were running everywhere. Now I drink soda.”

“Thank you for staying sober,” Zenon says. We all start laughing again. The man sitting next to Zenon suddenly announces, “You think that’s bad? I had to drive him home. In my pickup. He still had his machetes. I kept shouting, ‘Don’t kill me!’ ”

The dominant tones and words from English are already crowding out the Spanish music among the younger generation. Several of the young ones rarely speak Spanish.

“I wanted to,” our sober amigo admits. We apparently think this is the most wonderful thing we’ve ever heard.

Zenon confides in me: “I like an American thing they have. Scratch cards. It’s like the lotería in Mexico, no? I can’t stay away from scratch cards at gas stations. Once, I was doing a job in another state, and I was riding home with my boss. He stopped for gas, and I borrowed money from him and went inside and played the scratch card. And I won! I won a hundred dollars.”

Then he turns melancholy.

“I didn’t know English. The card said WK under the numbers. The attendant looked at it and gave me the money, then tucked the card in his pocket. I learned later that the WK meant cada semana.” (One hundred dollars weekly.) “I thought Americans were honest.” We ponder this chicanery. “It could have changed my life.”

He wanders sadly to the small couch beside the Happy Birthday display and falls asleep.

“He’s tired. He works hard,” the machete wielder confides.

Lowenstein announces that these parties typically go till 6 a.m. Gaby, in her pretty flowered birthday dress, nods. I don’t have time to react to this, since Doña Lupe, the Chicago matriarch who was the first in the family to immigrate and who still lives on the South Side, has come to rusticate with the suburbanites.

She floats through the rooms like a movie star, hands extended as if in a blessing. I stand to greet her and reach out my hand. She looks at it and offers me the tips of three fingers. Doña Rosa is rocking the kitchen in her fresh floral dress. Gaby takes her place at the gift table beneath the balloon arch, and the singing begins.

South Side Chicago. Lowenstein is driving—until he sees some weird thing on the street and jumps out of the car to snap 50 or 60 pictures. His first astonishment of the day is a window with a stuffed wolf standing watch over Halsted Street.

When we get under way again, I’m amazed that Pilsen, Little Village, and Back of the Yards are neighborhoods both gentrifying and becoming more Tijuana-like. By Tijuana, I mean the wild colors and improvisations. One building sports a mural of Pinocchio, to which a graffiti artist has added: “The South Side Is A Good Place To Live.”

Since the birthday party a few weeks ago, several members of the family have been struck with a mystery illness. Coughing, exhaustion. Not, apparently, COVID. Even the powerful Doña Lupe is in bed.

But we drive to her home to see her famous elote cart—the miraculous wheeled cart that corn sellers push through every border town. Hers is parked in front of her row house, like a monument.

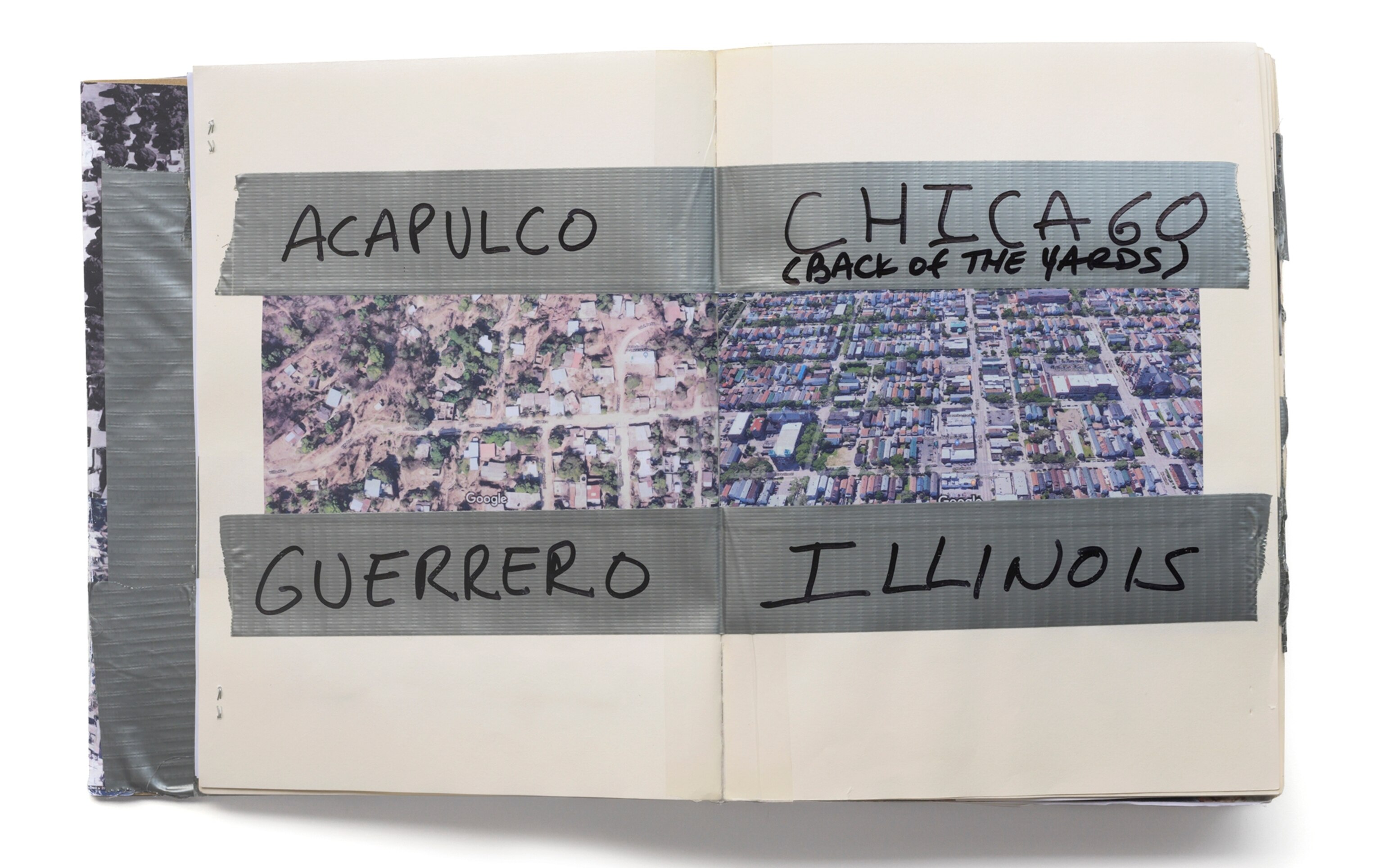

A drive around the block tells the story of immigration to Chicago: a rough-looking old apartment, then a house. An elote cart, then around the corner, a swap meet where Doña Lupe organized and made a financial opening for others, regardless of immigration status. Then, around the corner and up the street, neat bungalows where later generations live. They include young people like Elizabeth (“Eli”), the first in her family to attend college. The entire tale in one short paragraph.

Lowenstein and I collect Eli and head back west, to the cornfields and the house that hosted the birthday party. When we get there, the place is quiet. Even the mighty Don Chava is ill. He had a terrible headache, and Gaby put him to bed. The little ones are still in evidence, though the volume is greatly reduced.

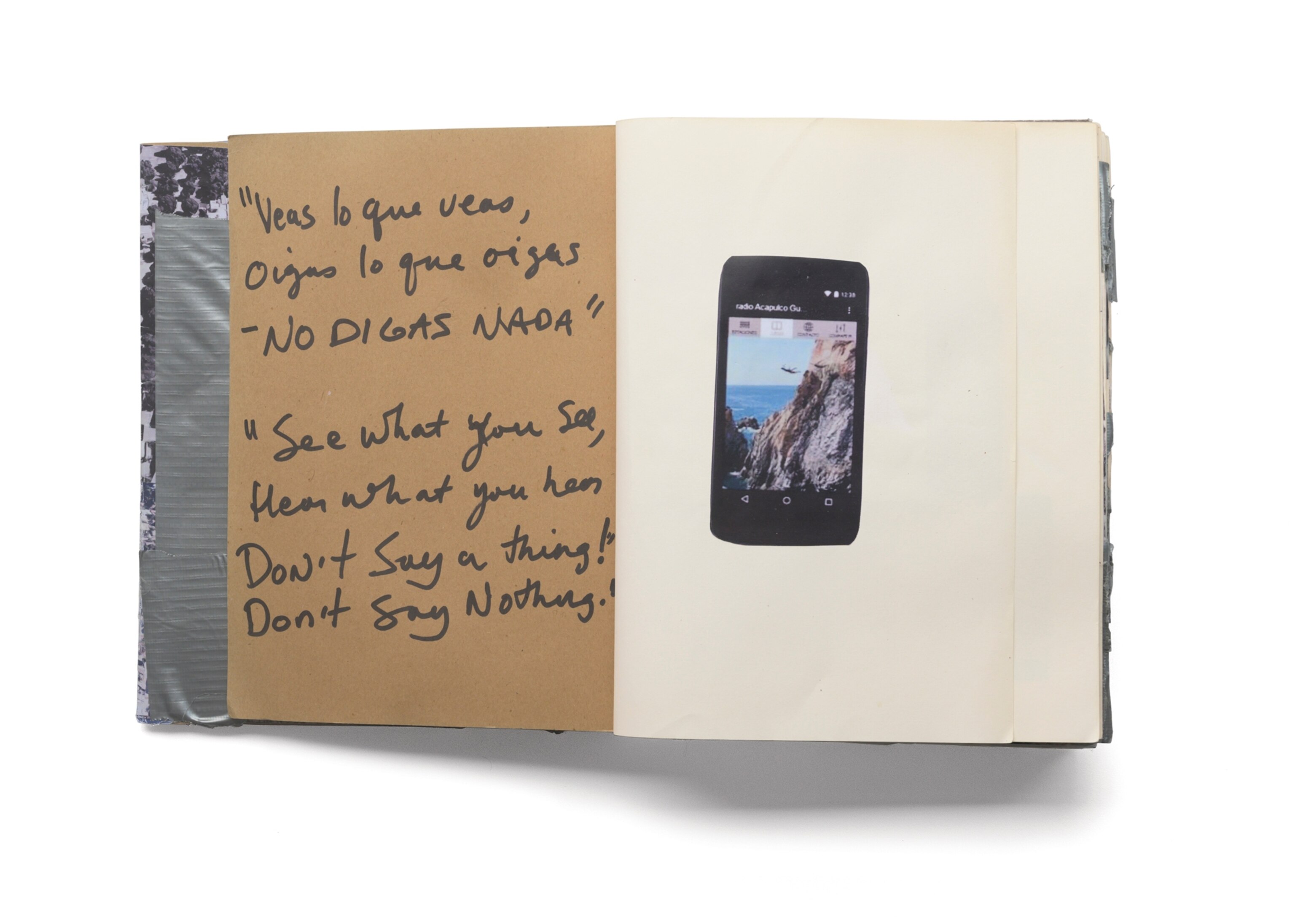

Doña Rosa sits with me at the table and talks to me as if I were her nephew. Tales of gardens and families and homelands and narcos. (“If they know you, they are the best people to know, because they protect you. If they don’t know you … it’s not so good.”) Gaby sits with us, relaxed. We are suddenly part of a fabulous Spanish term: entre familia. Among family.

We are suddenly part of a fabulous Spanish term: entre familia. Among family.

Everybody is sad that Doña Rosa is flying to Utah. (Ootah.) Especially Zenon, who heard that Utah has mountains. Doña Rosa has family there too. She wants to see them all before the awful cold and snow hit Chicago. She wants Eli to come, but Eli has a job.

“I worked hard this week,” Gaby says.

Here?

“No, no. I work with the yard crew. I blow the air. Blow the leaves.”

“Everybody works,” Doña Rosa says.

“Gracias a Diós,” Gaby replies.

As we leave, she gives me a full meal wrapped in foil for my wife. And two slices of birthday cake from our party.

“When you come back, bring her. She’s family now. We have parties every Saturday. And then we can have breakfast.”

The fat sun wobbles over the cornfields as we head home, peaceful as a painting, an American vista.

Luis Alberto Urrea is a Pulitzer Prize finalist and Guggenheim Fellow who has written 19 books, including the national bestseller Good Night, Irene. Born in Tijuana to a Mexican father and an American mother, he is often known as a border writer. But, he says, “I am more interested in bridges.”

This story appears in the November 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine.