Why your family’s untold stories matter more than you think

Documents and genealogies are helpful resources, but personal memories are invaluable keys to understanding your family history.

The binder stared back at me. Yellowing papers and black-and-white photographs spilled out its sides. In handwritten Spanish, the label on its spine read “Historia Antigua.” Ancient History. I opened it to the first page and began to read.

I’m not sure what it is that I’m about to write, but I’ve had this idea for a number of years now, ever since a conversation I had with my father when I turned thirteen and had my bar mitzvah …

This was clearly my grandfather’s handwriting—a characteristically Argentine script marked by irregular capitalization. It was Thanksgiving, and I was in my grandparents’ basement in the suburbs outside of New York City. As I read on in silence, I could hear my extended family ambling about upstairs. Within the first few pages of the binder, Abuelo had recounted centuries of our family’s history, touching Mesopotamia, medieval Spain, Ottoman Syria, Latin America, and the United States, as it had all been told to him by his father. What I held in my hands was an oral history, and Abuelo was the first to write it down. As I gently flipped through the rest, I found diaries, travelogues, letters, and news clippings from Abuelo’s own youth, a treasure trove of recollections, remembrance, and research.

For several months I didn’t tell him what I’d found in his basement. Instead, I would look forward to college breaks and holidays at my grandparents’ house, when I could quietly slip away from the crowd to go downstairs and read more. One afternoon, months after I’d first found the binder, Abuelo came into the kitchen and motioned for me to follow him. “I want to show you something,” he said. He led me down to the basement, and as we turned left toward his library, I saw that the Historia Antigua was already open on the desk. My face flushed.

“You’ve been looking at my writing,” Abuelo said. My grandfather always spoke so matter-of-factly in English, carefully choosing his words.

“Yes, I have,” I said. “Abuelo, it’s very interesting.”

His face broke into a wide smile. He began to laugh as he spoke, and his eyes welled up with tears. “How much have you read?”

“Not much,” I lied. We sat down in front of the desk. Abuelo thumbed through the binder—past religious documents (a ketubah, or Jewish marriage contract) and past civil documents (a faded registry from Buenos Aires)—and he began to tell me the family story. From that day on, we mostly read the Historia Antigua together, so that Abuelo could explain the parts I didn’t understand: names and places, words and phrases in Spanish and Arabic and Hebrew. We discussed language, identity, and history; we drew and redrew family trees, and reviewed the names and backstories of ancestors as though they’d be coming over at any moment. These conversations drifted completely into Spanish. It was easier for Abuelo to talk about his life—especially his childhood in Buenos Aires—in his native language. For me, it lent a sense of excitement and even mystery to the conversation, sort of like unlocking a new world. As both a grandson and a journalist, I tried to ask questions that brought color and nuance to these histories. Since the Historia Antigua already covered the basics—the what, where, and when of my family’s story, at least in broad strokes—I could focus on the why and the how, to paint a portrait of our wandering family. Why did my Jewish great-grandparents leave Damascus in such a hurry at the start of the 20th century, bound for Argentina? Why did my great-grandfather decide to work as a traveling salesman with a horse-drawn cart in the remote Andes Mountains, and how did he go about his journeys? How did Abuelo and Abuela spend the days of their childhood in the working-class neighborhoods of Buenos Aires? And why did our family end up migrating again, this time to the U.S. and across the Americas?

Though it might be hard to believe that Abuelo hadn’t shared these stories with me before, I wasn’t necessarily surprised. My grandfather was never one to launch into a family tale unprompted—but then again, I hadn’t ever taken the time to ask. Whenever I told friends and others about our conversations, this last sentiment was repeated back to me. It’s amazing that you took the time to ask, people said, lamenting that they hadn’t yet done the same or didn’t think to until it was too late.

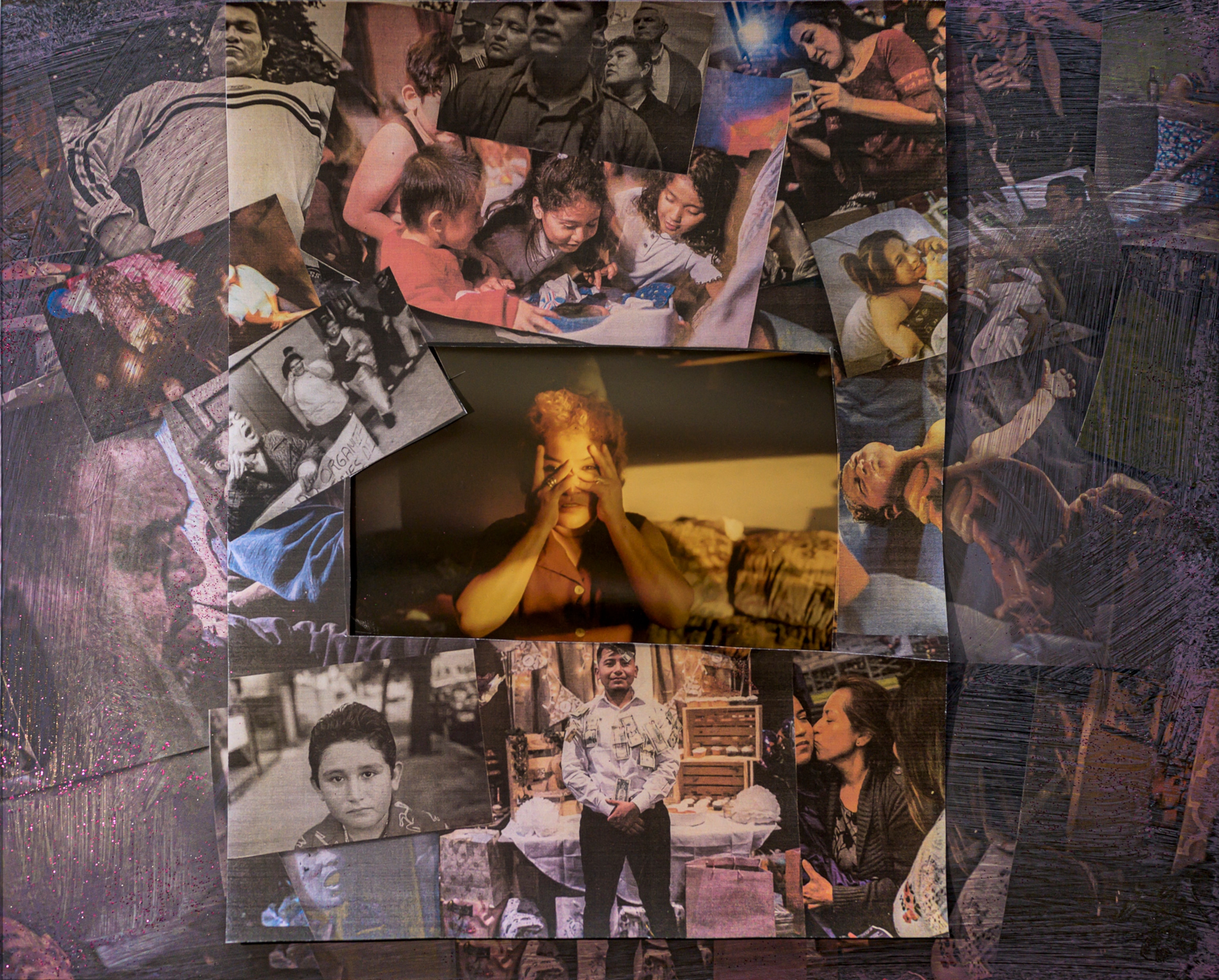

Recently, I began leading family history workshops and traveling the country to discuss a book I wrote about my search across Argentina for traces of Abuelo’s father, that Syrian Jewish traveling salesman in the Andes Mountains. What I’ve realized by talking with others is that time and inertia remain our biggest barriers to hearing our own stories. By the time the guardians of the answers are gone, we are more likely to be left with heaps of documents to sort through—birth certificates, DNA results, unlabeled photographs—rather than hours of stories (the where and when, but not the how and why).

For those of us still in the lucky position to do so, we must ask questions of our parents and grandparents now, before it’s too late. Keep journals, write letters, make lists of sensory details. Ask about otherwise ordinary objects around the house that could contain clues about the past. Record and transcribe kitchen table conversations—or if those conversations aren’t happening naturally, organize talk show–style interviews between older and younger relatives, with the rest of the family as the audience. If you are of an older generation, it is your turn to speak. Think about how you can make these stories come alive in your own families, and what sorts of tools—like Abuelo’s thick, mysterious Historia Antigua—you can use to light sparks of interest among your younger relatives as well as yourself.

Family stories are currency for survival. They are embedded within the traditions we pick up along the journeys of our lives. They are the identities we create in worlds foreign and familiar, remembered now but forever at risk of being forgotten.

A while after Abuelo and I began discussing the Historia Antigua, Abuela revealed her own secret collection of stories, short fictions inspired by her childhood, which she’d filed away in the back of her recipe binder. Now, as a family, we often read and discuss those too.

(20 holiday gift ideas from Nat Geo staff.)

Jordan Salama is the author of Stranger in the Desert: A Family Story, from which this essay is adapted.