How an obscure 1944 health law became a focus of U.S. immigration policy

Title 42 is coming to an end. What does it mean for those seeking refuge in the United States?

A record number of migrants have amassed at the United States’ southern border over the past couple of years in a bid for entry into the country. But officials have moved quickly to expel the vast majority of them using a public health statute known as Title 42.

That statute expires on May 11, creating a potential rush by migrants to get across the border to seek asylum before new rules kick in that would expedite deportations.

Here is a brief history of migration rules and how Title 42 came to be.

Who can and can’t enter the U.S.?

Since 1952, all migration into the U.S. has been subject to the Immigration and Nationality Act, an extensive collection of statutes that defines who may enter the country and who is turned away. The federal law defines individuals who lack U.S. citizenship and have not been naturalized as “aliens.” Non-citizens may be deemed ineligible for a visa or admission to the country for a variety of reasons including prior criminal convictions, evidence of drug abuse, or participation in a variety of human rights violations.

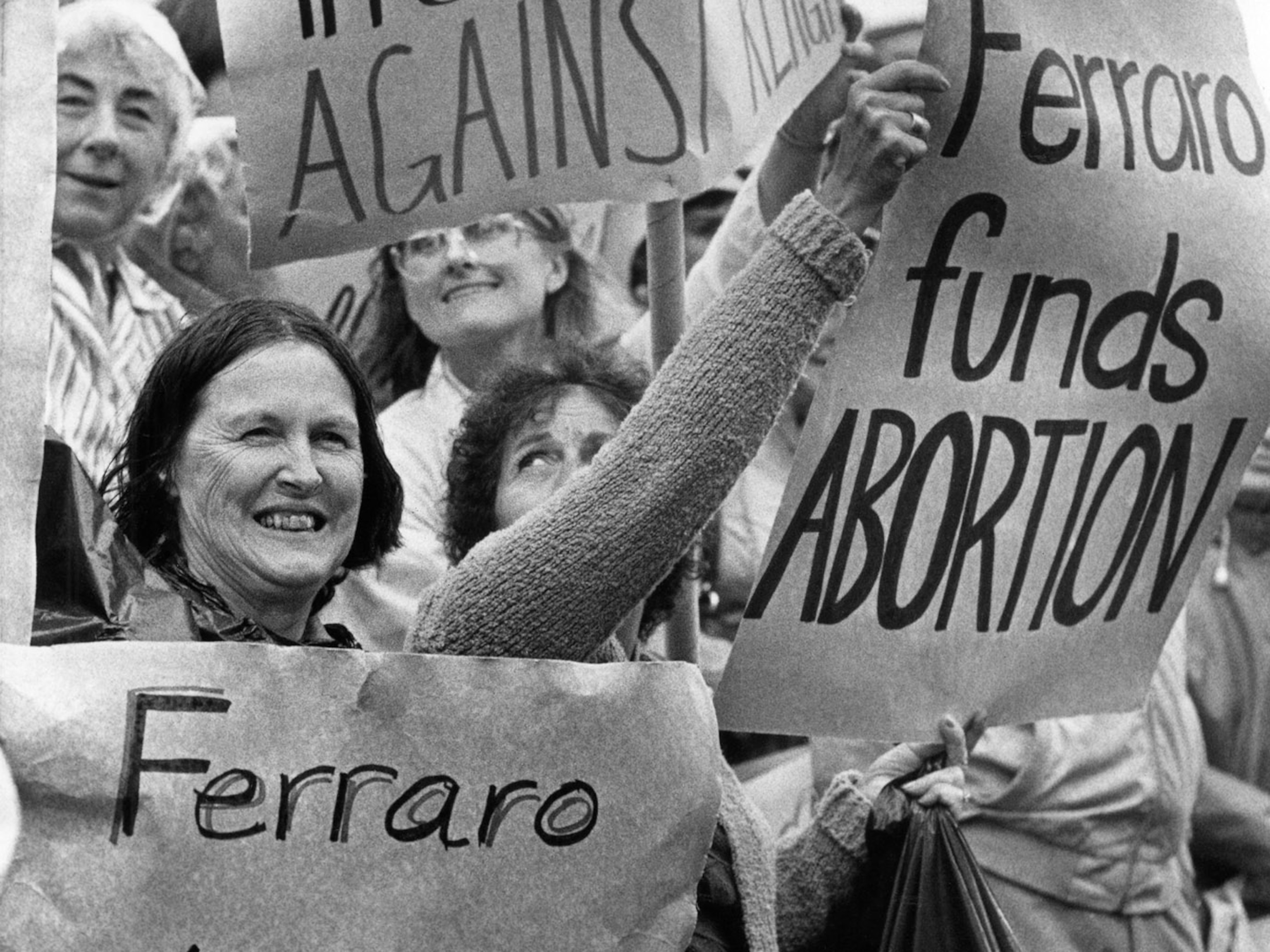

Some migrants, however, are considered refugees and may seek asylum under laws developed in the wake of World War II. The current law defines “refugee” as anyone who is unwilling or unable to return to their home country because they have been persecuted, or fear being persecuted, for their race, religion, nationality, membership in a social group, or political opinion. People who have been or have been threatened with forced abortion or sterilization also qualify for asylum requests as refugees. It is not known how many of the migrants currently at the border fall into any of these categories.

(Read our series on Stories of Migration)

For the past quarter-century, non-refugees seeking entry without a visa have been subject to a process known as expedited removal. The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act empowered immigration authorities to order the immediate removal of any non-citizen they suspect is ineligible for entry unless they express their intention to apply for asylum or a fear of persecution that would qualify them for asylum.

At first, expedited removal was only used in limited cases in which a non-citizens attempted to enter the country using fraud or misrepresentation, either when they failed to present eligible documentation at the border or by sneaking into the country through another means. In 2004, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) extended the practice to people apprehended within 100 miles of the U.S. border within 14 days of entry, and within up to two years for those apprehended at sea.

Then, in 2017, President Donald Trump directed DHS to implement expedited removal to the full extent of the law. The direction was first implemented in 2019. The new policy expanded expedited removal to cover non-citizens apprehended anywhere in the U.S. who have been in the country for less than two years.

The process “has far fewer procedural protections than formal removal proceedings,” wrote legislative attorney Hillel R. Smith in a 2020 report provided to Congress by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service. Smith noted that those who fall under the policy have no right to counsel, a hearing, or an appeal, and that non-citizens are required to be detained pending expedited removal.

Pandemic-era changes to immigration enforcement

In March 2020, the Trump administration further adjusted immigration enforcement by invoking Title 42 of the U.S. Code. It’s part of the Public Health Service Act, a 1944 law giving the federal government authority to suspend “the introductions of persons” into the United States to prevent the spread of a communicable disease.

The 1944 law was not intended originally to apply to asylum seekers, says Blaine Bookey, legal director of the University of California's Center for Gender & Refugee Studies. "It’s a very obscure statute,” she says. “People expelled under Title 42 are not afforded even the minimal protections an expedited removal process would have.”

The center has participated in challenges to the legality of the policy in federal court along with a variety of other civil rights and immigrant rights groups. But though a federal judge ordered a preliminary injunction that would have halted Title 42 removals in November 2020, the practice continued, even after President Joe Biden took office in January 2021.

The Biden administration now is expected to roll out new measures and has dispatched 1,500 U.S. troops to the border to help deter the surge of migration. How effective those actions will be remains to be seen.