California’s ‘Ellis Island’ was designed to keep Asian immigrants out

The majority of immigrants who passed through California’s immigration station, Angel Island, were from China and Japan—and tens of thousands of them were detained there.

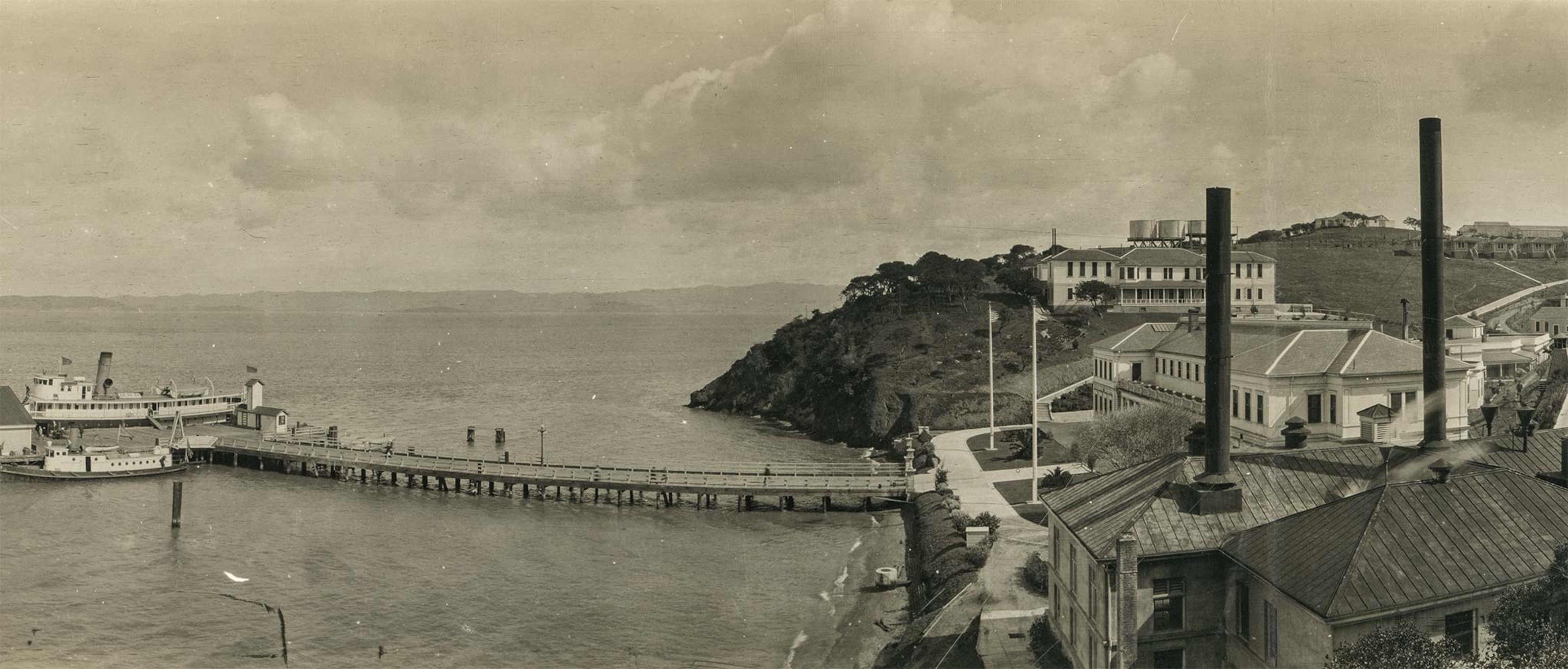

Though often referred to as the Ellis Island of the West, the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco harbor was built in 1910 not to welcome people to America but to prevent many, particularly those from China, from entering the country.

In the 30 years it operated as the West Coast’s main immigration center, Angel Island processed some 500,000 immigrants from 80 countries, including Russia, India, Mexico, Korea, and the Philippines. The majority, however, came from China and Japan. Experts estimate that some 175,000 Chinese and 60,000 Japanese were detained there.

(How Ellis Island shepherded millions of immigrants into America.)

Chinese exclusion

Asians immigrating to the United States faced blatant racism. Discrimination against Chinese people especially had been brewing for decades—since they first arrived in large numbers in California in the 1850s. Lured by a gold rush and promises of work on the transcontinental railroad and on farms with a shortage of field hands, they fled tough economic and political conditions in southern China.

Many of them hoped to send money back to the families they’d left behind, and some owed debts for their passage to America. Out of desperation, they often accepted low wages and worked long hours, angering some white workers who believed the Asian immigrants were stealing jobs from them.

(They tried to take this Chinese-American's citizenship. He fought back and won.)

In the 1870s, as more immigrants arrived over the years and the U.S. economy slowed, anti-immigrant sentiment grew. Chinese laborers often became scapegoats for the country’s problems. Prejudice and discrimination became pervasive and even led to violence.

Racism was so widespread that multiple efforts specifically targeting Chinese immigrants were made at the local and state levels, culminating in the federal government’s passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The law banned admission of Chinese laborers to the U.S. for 10 years with the exception of a few groups, including diplomats, students, and children of U.S. citizens. It also denied them a pathway to naturalized citizenship. The legislation was the first in American history to limit immigration based on race or ethnicity.

Stuck on an island

With the exclusion act in effect, all incoming Chinese had to be closely evaluated by U.S. immigration officials. Arriving in San Francisco Bay, they were initially processed at the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s two-story wooden shed on the waterfront, which became crowded and unsanitary. After the Chinese community repeatedly raised complaints about the conditions, the government took steps to find a new location.

Angel Island was chosen as the new site in large part because it was isolated from the mainland, giving authorities greater control over those awaiting admittance. There were other advantages: Its location would make it harder for detainees to escape, stymie immigrants trying to connect with family and friends already in San Francisco, and help prevent the spread of communicable diseases.

Despite an outcry from the Chinese community objecting to Angel Island’s remote location, construction went forward. The station opened on January 21, 1910, and included an administration building, a hospital, a wharf, and detention barracks with a guard tower. Barbed wire fences enclosed the station.

With the station operational, U.S. officers boarded all ships arriving from Asia and separated passengers by nationality and class. Europeans and others in first and second class were usually allowed to disembark quickly. Those in steerage, who had medical concerns, or who were seeking exemptions to the Chinese Exclusion Act were sent to Angel Island.

(Restoring Hawaii's forgotten World War II internment sites.)

Upon arrival, they were immediately given full medical examinations. Those who failed were deported. Those who passed faced a Board of Special Inquiry that interrogated them about their exemption claims.

Paper children

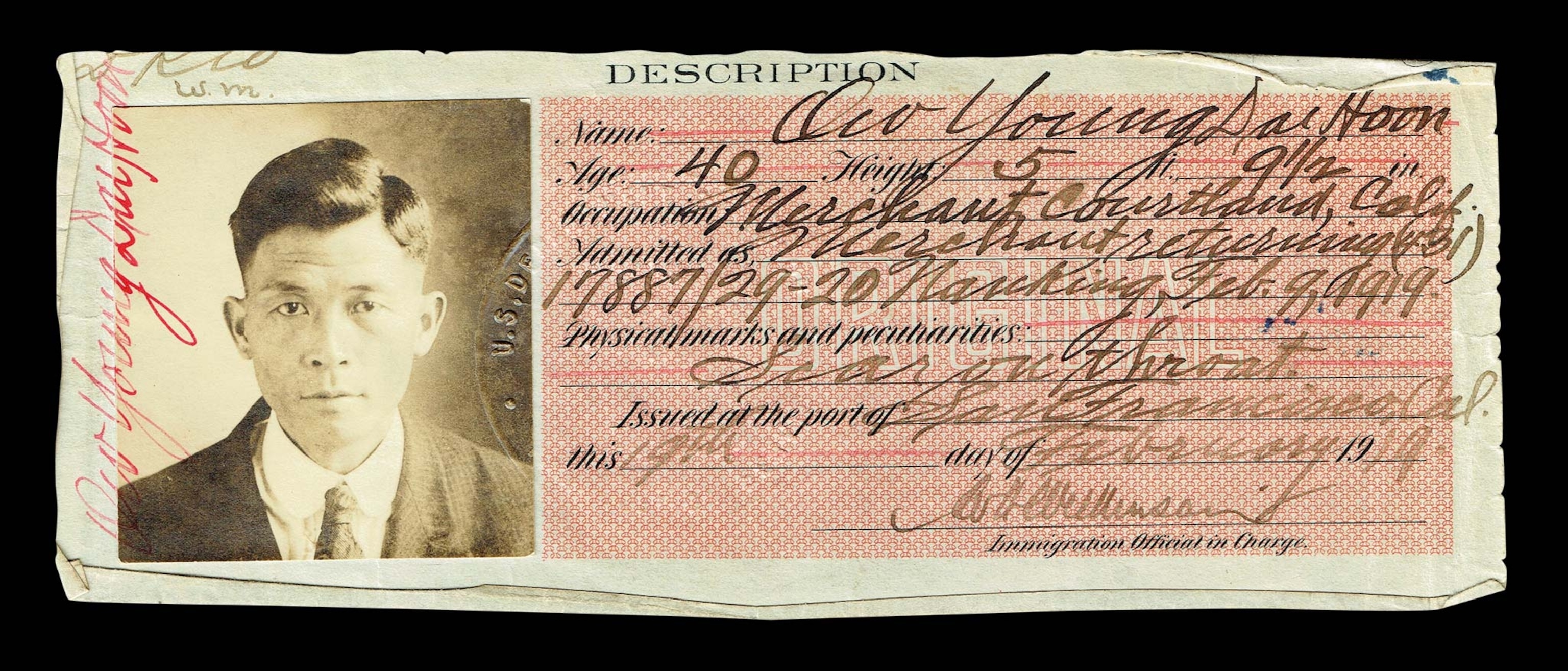

Desperate to be admitted, some Chinese fabricated relationships with U.S. citizens. Fires from a 1906 earthquake had destroyed San Francisco’s municipal records, making it difficult for authorities to confirm the citizenship of declared family members.

Others paid already settled Chinese Americans to falsely state that they were their children. A trade in “paper sons” and “paper daughters” soon thrived. To weed out fraud, inspectors asked immigrants a barrage of questions about their family, homes, and villages back in China—questions such as,“Where is the rice bin kept?” or “How many windows does your house in China have?” Sponsors were also interviewed to see if the answers aligned. To prevent those claiming exemptions, even legitimate ones, from making mistakes, Chinese parents and “paper parents” sent letters or “coaching books” to those seeking entry.

Seeking safe haven

Inquiries by the board could take a couple of days, but the average detainment was two weeks. Any discrepancies, however, quickly raised concerns. In some cases, immigrants were held as long as two years while they appealed the board’s decision to deport them. Meanwhile, they lived like prisoners: Their dorms were locked, and they couldn’t leave the building without a guarded escort. Their letters and packages were examined, and they were refused visitors.

(What can the transcontinental railroad teach us about anti-Asian racism?)

Abandoning Angel Island

The immigration station was finally relocated to the mainland in 1940, but the Chinese Exclusion Act was not repealed until 1943. Even then the U.S. continued to limit immigration from China to just 105 people a year until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which ended admissions policies based on race and ethnicity.

The Army took over Angel Island during World War II, using it as a detention facility for Japanese immigrants and a processing center for German and Italian prisoners of war. It was eventually abandoned after the war, and the island became a state park in 1963.

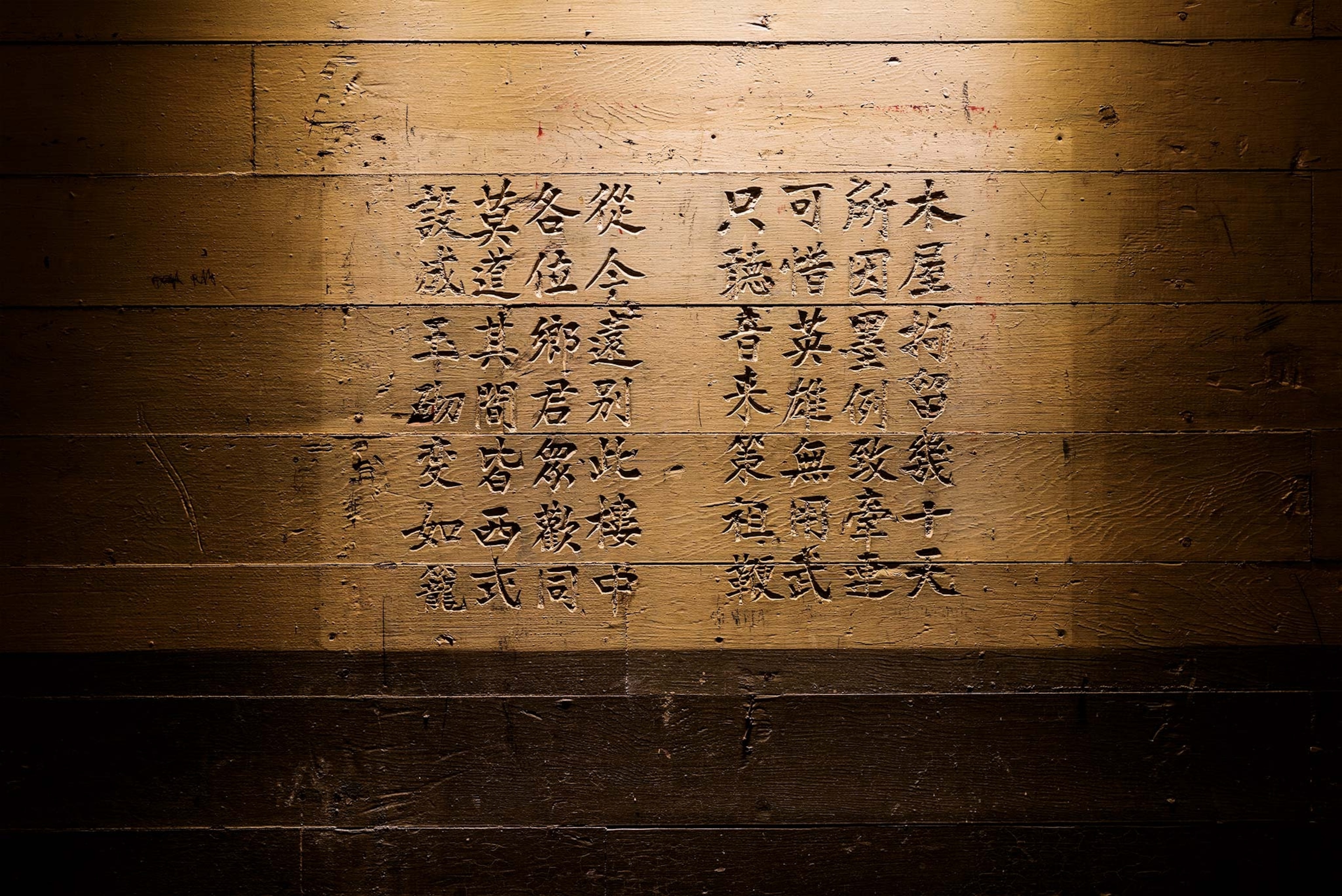

The station was set to be demolished when a park ranger uncovered poems written on the walls of the detention barracks. Efforts were made to preserve them, and in 1997 Angel Island was designated a National Historic Landmark. It is now open to visitors as a monument to the immigration experience on the West Coast and the difficulties faced by those detained there.