Why smallpox vaccines fell out of use—and what that means for monkeypox

Smallpox vaccines have been approved for monkeypox. But experts warn that many questions remain about the protection they provide and how to best administer them.

Gregory Poland has been vaccinated against smallpox three times—a necessary precaution as a member of a bioterrorism response team—and he has unpleasant memories of each one. Unlike typical modern vaccines, the smallpox vaccine he received contained live virus applied directly to the skin on his arm, which was then punctured 15 times with a bifurcated needle.

Poland, a vaccine researcher at the Mayo Clinic, says the scar left by the process “itched like mad.” Worse, the live virus it contained meant the scar would remain infectious for a month, during which time Poland had to keep his distance from others—even sleeping in a separate room from his wife.

Poland is part of a shrinking population who have been vaccinated against smallpox. Thanks to an historic global vaccination campaign, the disease was eradicated in 1980, meaning the young adults of today weren’t alive when smallpox vaccines were routine. Now, however, monkeypox is driving new demand for the smallpox vaccine. Although monkeypox is far less dangerous than smallpox, the two viruses are related—and there is some evidence that the smallpox vaccine provides protection from monkeypox.

(Why monkeypox cases are still rising at such an alarming rate.)

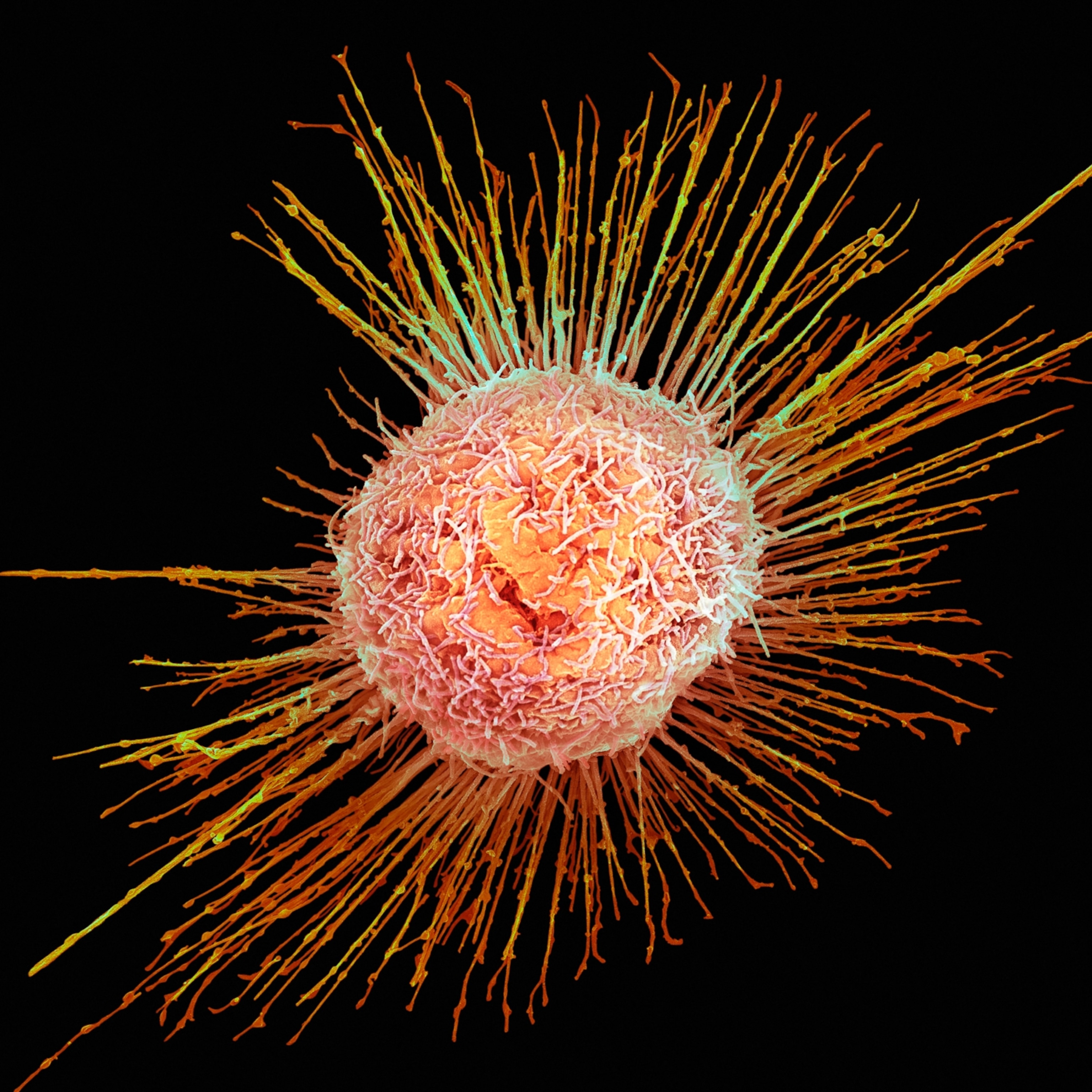

“The reason we don’t routinely give it is that it’s one of the most reactogenic vaccines we have,” Poland says. The classic smallpox vaccine has serious side effects, including encephalitis and myocarditis. About a third of people can’t get it because of medical conditions, including pregnancy, cardiac disorders, and suppressed immune systems.

Yet despite the development of safer vaccines that are easier to administer than the one that Poland received, rolling them out to the public has proven fraught. Supplies are low, in part because more than 20 million doses were allowed to expire in 2017. But even if there was enough smallpox vaccine to go around, experts say most people don’t need it—and that many questions remain about how it works against monkeypox.

Origins of the smallpox vaccine

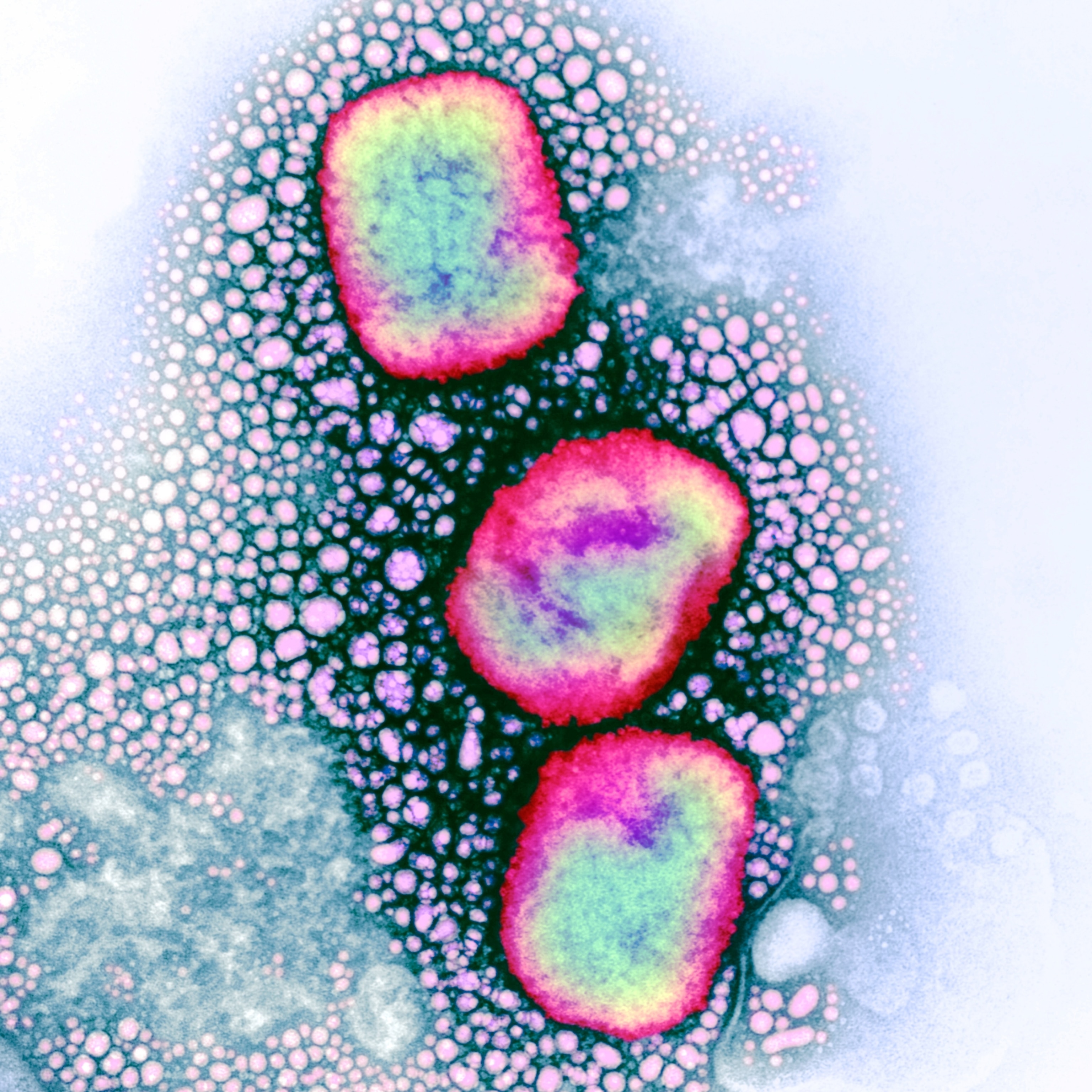

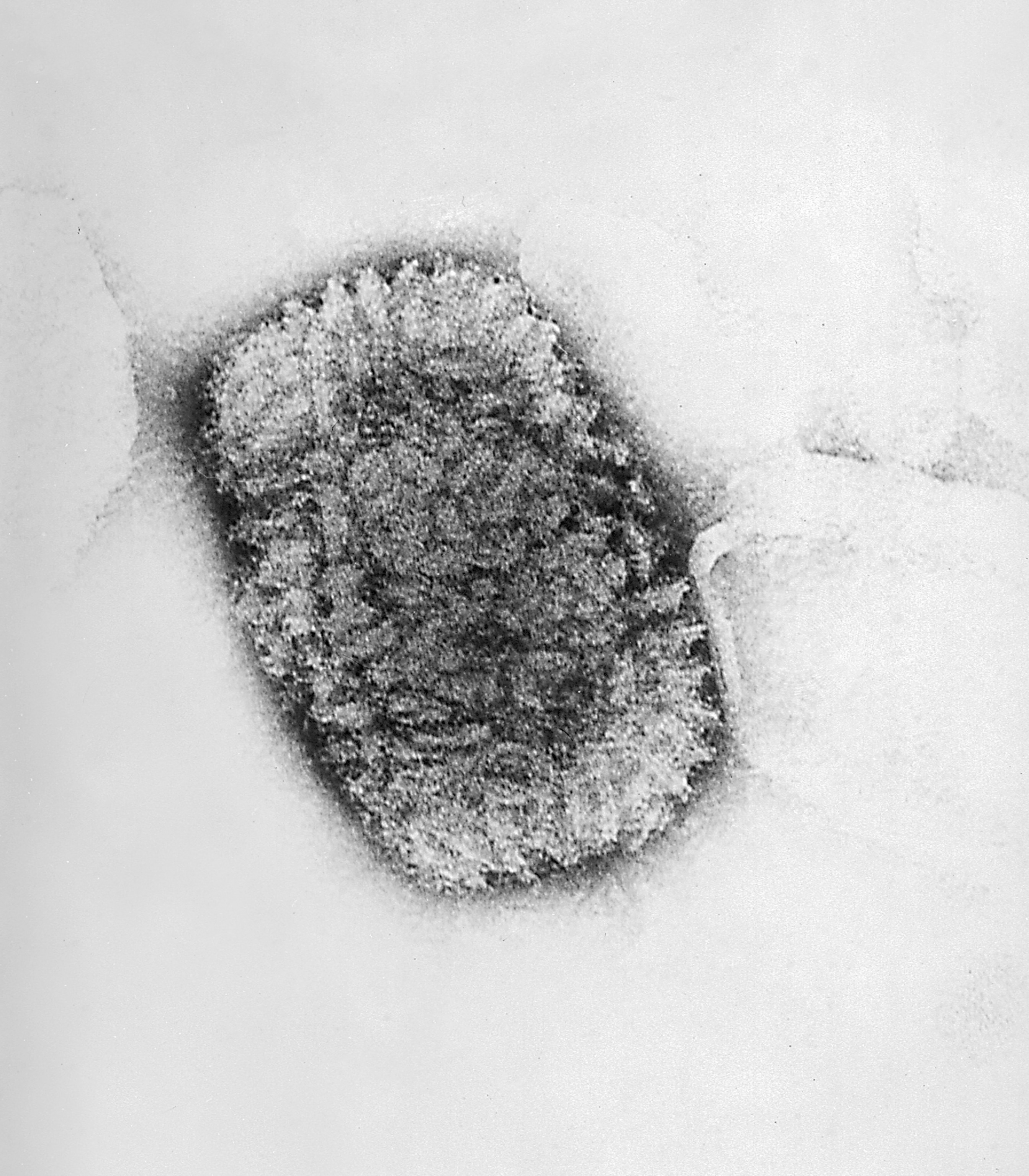

Smallpox is caused by the variola virus, a large double-stranded DNA orthopoxvirus. Its name is derived from the Latin word for “spotted,” a reference to the raised bumps that break out across the skin of its victims and leave lasting scars, or pockmarks.

(Learn more about smallpox and the variola virus.)

Although its origins remain murky, the earliest evidence of smallpox dates back some 3,000 years to ancient India and Egypt. Spread through body fluids and direct contact with infected people or contaminated objects, the disease killed about 30 percent of the people it infected—and is thought to have contributed to the decline of the Aztecs and Incas.

Attempts to curb smallpox are almost as old as the disease itself. Sanskrit texts dating to 1500 B.C. describe attempts at variolation, a method of inoculating people by exposing them to the materials from a smallpox sore. But modern-day vaccines trace their origins to the work of Edward Jenner in 1796. Jenner discovered that inoculating people with cowpox, a milder relative of smallpox, protected them against the disease.

In the 19th century, the vaccinia virus, another member of the orthopoxvirus family, replaced cowpox in the vaccine. Grown in the skin of baby calves—which comes with a risk of contamination from pathogens—the first generation of smallpox vaccine wasn’t ideal. But it allowed governments to embark on a global mass vaccination campaign in the 1960s. The last naturally occurring case was recorded in Somalia in 1977, and in 1980, the World Health Organization officially declared the disease eradicated.

By then, many countries, including the United States, had already stopped administering the smallpox vaccine since the disease no longer posed a threat to their populations. “It was a more exotic travel disease even by that point,” Poland says.

Developing new generations of smallpox vaccine

Still, concerns remained that terrorists could weaponize the virus. So even as the U.S. disposed of much of its first-generation jabs in the early 2000s, it developed a new one, ACAM2000, for emergency use. Grown using modern cell culture methods, this vaccine had none of the impurities of the first generation—but it did have a poor safety profile.

When the U.S. began to use ACAM2000 to vaccinate its military forces after 9/11, “the side effects became quickly apparent,” says Raina MacIntyre, an infectious diseases expert at the University of New South Wales in Sydney and a member of WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization.

Although rare, some people who received the vaccine suffered from inflammation in their hearts and brains. And, like the first-generation vaccine, it used live virus that could replicate inside the body, which was particularly dangerous for people with weakened immune systems and other medical conditions.

Another disadvantage of ACAM2000 became clear over time as smallpox vaccination became an increasingly rare medical procedure. “There would be very, very few people in America who would know how to administer the vaccine,” says Poland.

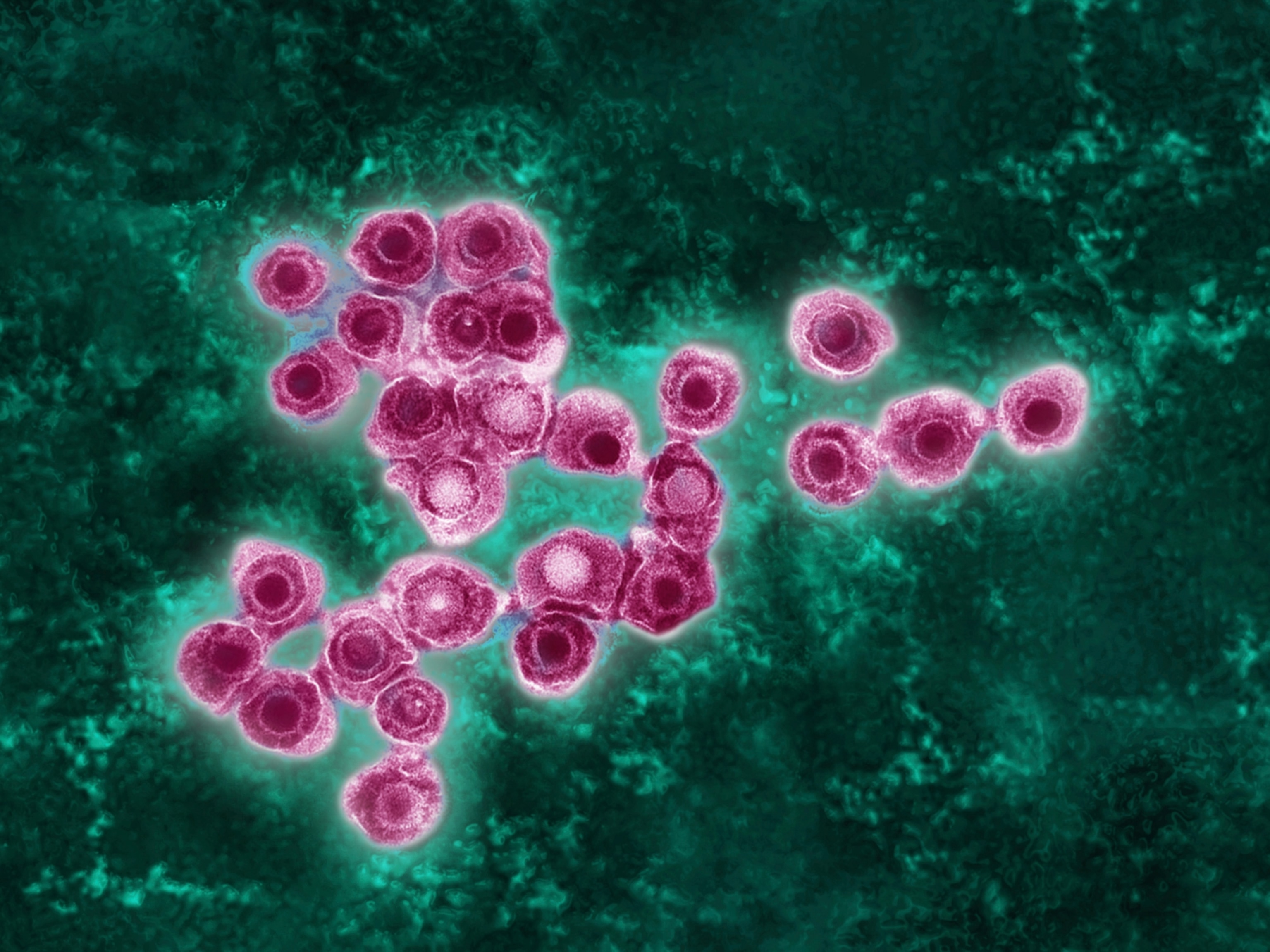

Fortunately, a new generation of smallpox vaccine has arrived. In 2019, the FDA authorized a vaccine called Jynneos—known as IMVANEX in Europe and Imvamune in Canada. The two-dose jab contains a modified version of the vaccinia virus that doesn’t replicate, which experts say make it safer for people with underlying medical conditions. Meanwhile, Japan has licensed another smallpox vaccine, LC16m8, which has also been tweaked to limit its ability to replicate.

Although many questions remain about these new vaccines, they offer some promise as the world grapples with an unprecedented outbreak of a different orthopoxvirus: monkeypox.

Monkeypox and the smallpox vaccine

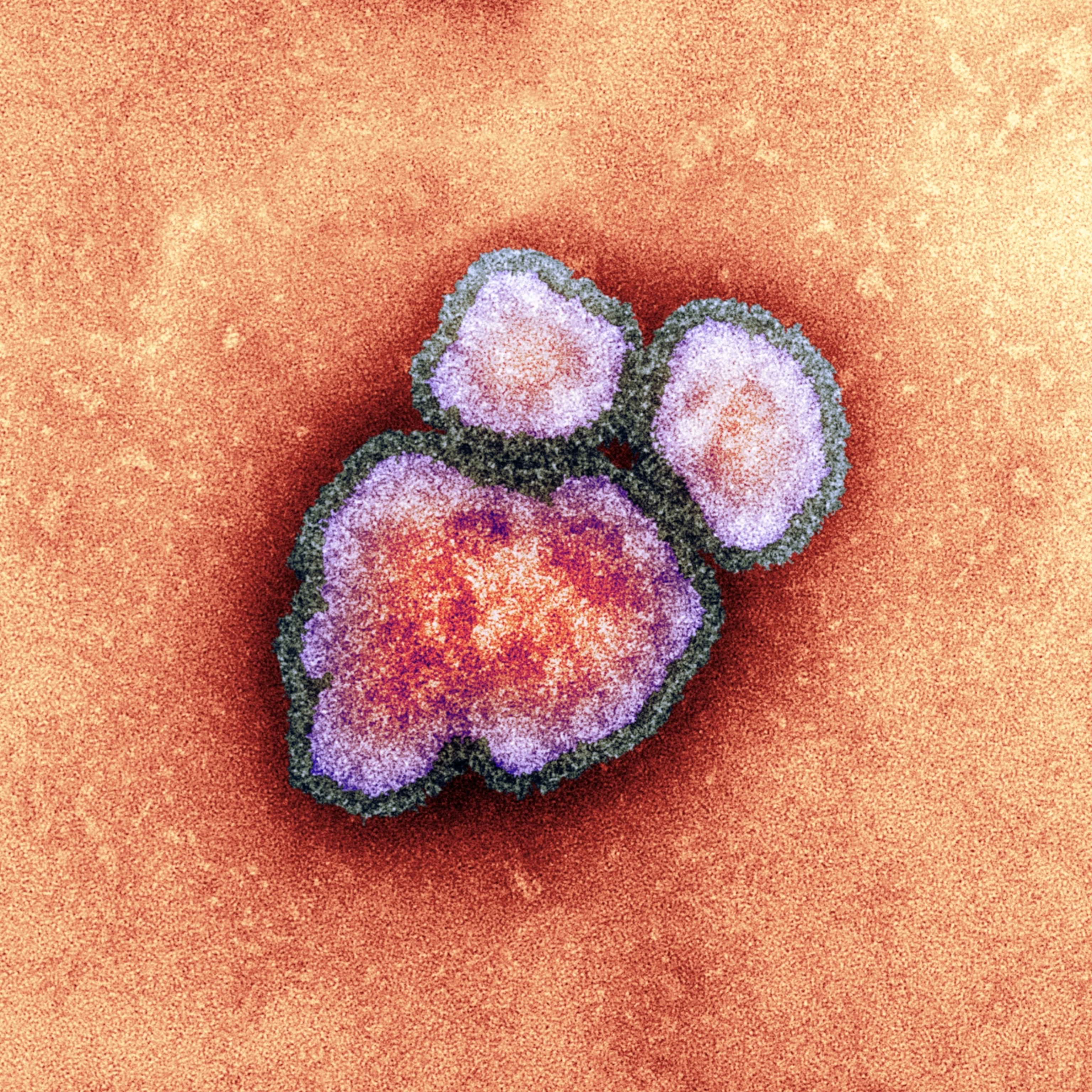

Discovered in monkey research colonies in 1958, the first human case of monkeypox was reported in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo. It is less transmissible and less dangerous than smallpox, killing only 3 to 6 percent of those infected. Unlike smallpox, monkeypox circulates among animals, making it particularly challenging to eradicate the disease.

However, early evidence suggested that people who had been inoculated against smallpox might fare better against monkeypox. In 1988, researchers in Zaire analyzed monkeypox case rates in people with and without smallpox vaccination scars. The study concluded that the smallpox vaccine was 85 percent effective in protecting against monkeypox.

MacIntyre says that, historically, monkeypox outbreaks were rare and small, with case numbers in the single or double digits. But that has been changing in recent years. A 2010 study conducted in the DRC found a 20-fold increase in human monkeypox cases—with a disproportionate number of the infections in young people who had never received a smallpox vaccine.

“Then in 2017 we started seeing very big outbreaks in Nigeria and then the Democratic Republic of Congo,” MacIntyre says. Her team’s investigation of Nigerian outbreaks between 2017 and 2020 found that cases were linked to declining levels of population immunity—which increasingly consists of young people who had never received the smallpox vaccine, as well as older people whose decades-old protection had begun to wear off.

Still, the theory that smallpox vaccines protect against monkeypox is not settled science, says Wafaa El-Sadr, founder and director of ICAP, a global health institute at Columbia University. While these studies do suggest that older people who were vaccinated against smallpox may have some protection, she says, “we don’t have any data to support this definitively.”

The knowledge gap is particularly wide when it comes to the new vaccine, Jynneos. The only studies so far that have demonstrated the vaccine’s effectiveness against monkeypox were done in animals, not humans, El-Sadr says. It’s also unclear whether Jynneos is safe for use in children, who are more susceptible to severe monkeypox. And, as the U.S. proposes stretching out its vaccine supply by injecting smaller doses between the layers of skin, rather than into the fat under the skin, the data to support the move is thin.

“I can list many, many questions that need answers,” El-Sadr says. “The good news is that we have a vaccine in hand that in all likelihood should be effective against monkeypox in humans.”

So who should get the monkeypox vaccines?

The monkeypox outbreak doesn’t mean that smallpox vaccines are about to become routine again. After all, the decision to administer any vaccine must balance the risks with the benefits.

Jynneos may be safer than the older generation of vaccines since it doesn’t contain live virus, but it still poses some risk of side effects, such as flu-like symptoms or an allergic reaction. Additionally, monkeypox is overwhelmingly being transmitted among men who have sex with men—meaning the risk to the rest of the population is low. “If there’s no benefit [to taking the vaccine], then no amount of risk is worth it,” Poland says.

Experts also say there’s no urgent need to distribute the vaccine as a preventive measure, as was done with the COVID-19 vaccine. The smallpox vaccines are effective after exposure—so it makes more sense to prioritize jabs for people who are concerned they may have been infected.

Of course, this risk-benefit analysis could change depending on what happens next. “If it’s limited and we are able to stop this outbreak in its tracks, then it makes it very difficult to say that we should recommend this vaccine for everybody,” El-Sadr says.

If the U.S. fails to contain monkeypox, however, then perhaps wider vaccination would be necessary—particularly if it spills into the animal reservoir and becomes endemic. Vaccination recommendations could also change if monkeypox begins circulating widely among children, who are at greater risk than adults.

El-Sadr is hopeful that this won’t come to pass. “Thankfully this virus is very different from smallpox and the consequences of getting monkeypox is very different from smallpox infections,” she says. “We have an outbreak, that’s true, and that’s a great concern. But we’re fortunate we have right here at our fingertips a test that can make a diagnosis of monkeypox, a vaccine we can use and hopefully scale up, and we also have a treatment.”