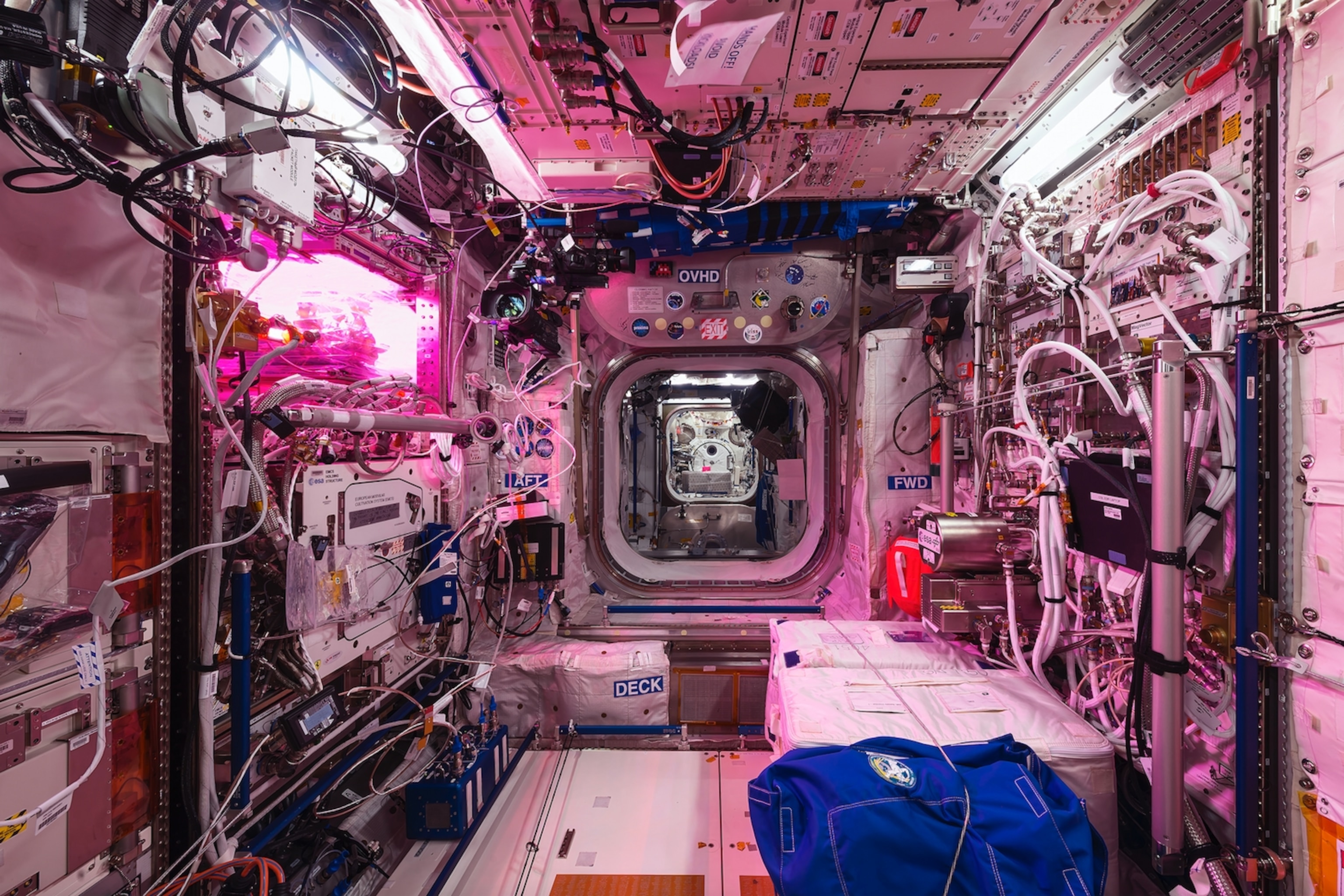

Eerily deserted images of the ISS give a unique perspective on life in space

The photographs, shot during astronauts' sleep hours, focus on the object they have called home for 20 years—and capture the experience of being human in a place devoid of humanity.

Italian astronaut Paolo Nespoli has spent a total of 313 days living aboard the International Space Station. In 2017, during the last of his three missions aboard, he collaborated with an Earth-based photographer called Roland Miller. Together the duo created a book that focuses solely on the station interiors.

They call their work “space archaeology”—a study of the items that astronauts use, and the spaces they inhabit. “It's a documentation of what we, the human species, have been capable of achieving in space, not only from a technological point of view, but also from a human point of view,” Nespoli says. “Just look at the complexity and intricacy of this high-tech marvel along with all the little signs we have dispersed around it to make it cosy, livable, and civilized.”

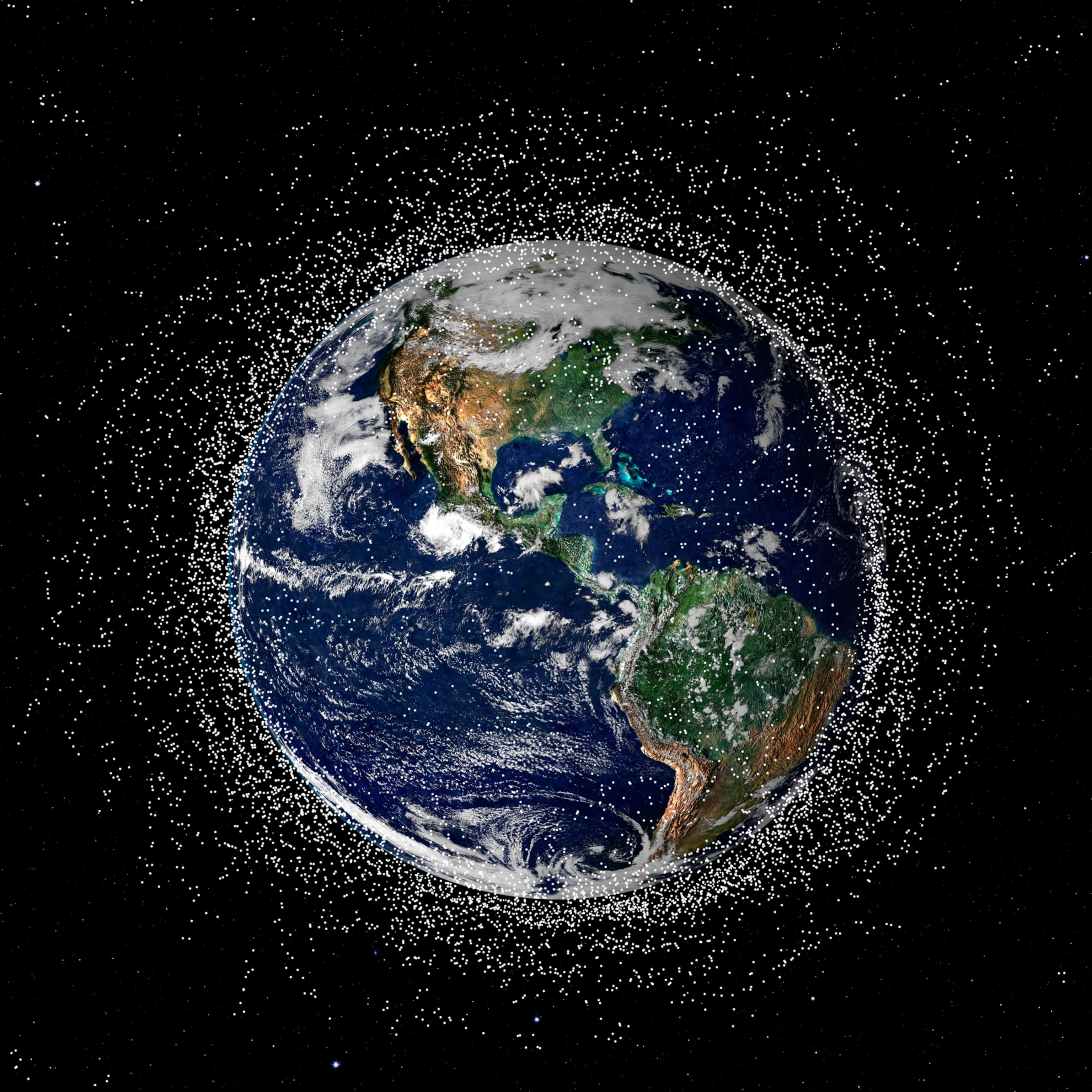

The book’s release coincides with the 20th anniversary of when humans first started living aboard the station. In this interview, Nespoli explains what life is like inside a spacecraft the size of a six-bedroom house, spinning at 17,500mph in Earth’s orbit.

The photographic project

Born in Milan, Nespoli embarked on his career in 1991 at the European Space Agency in Cologne, Germany, initially training other astronauts. Five years later he transferred to NASA, in Houston, Texas, and soon became an astronaut himself. On three separate occasions he lived and worked aboard the International Space Station, chalking up 313 days in total. Now 63 years old, he retired from service in 2018 and still lives in Houston with his wife and two young children. They plan to relocate soon to Italy.

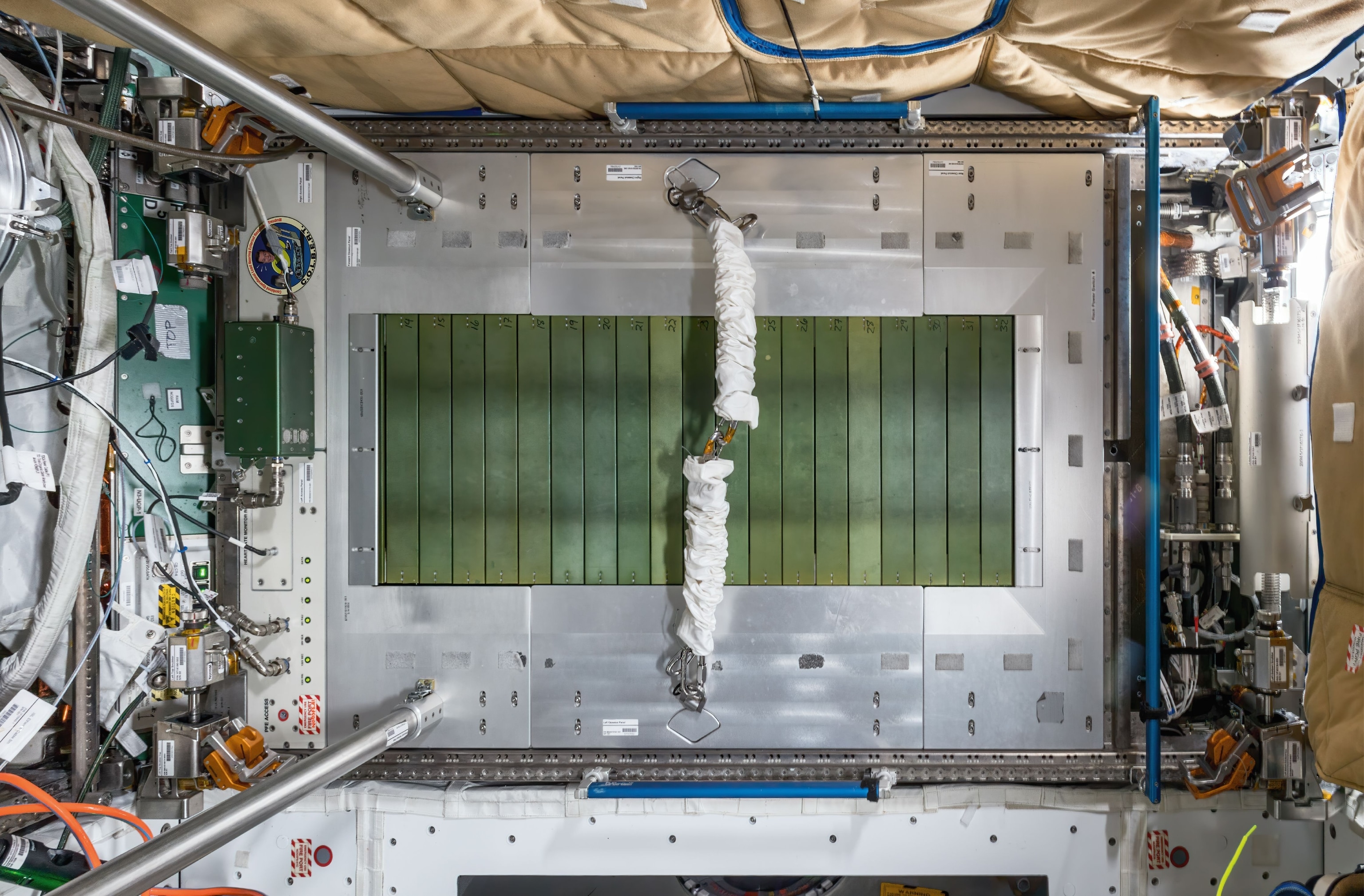

The space station is inhabited by up to six astronauts who spend most of their time conducting experiments or maintaining the station itself. While millions of photos have been captured of these men and women at work, until this project, few existed of the interiors alone.

Directing the photos back on Earth, Miller—a U.S.-based fine art photographer with a specialism in space—relayed his instructions to Nespoli up on the space station. As the latter explains: “Roland hoped he would have control of the framing and all technical parameters from the ground—much like directing a rover on a faraway planet. In fact, things turned out to be much more complex.” Nespoli took most of his photos during sleeping hours in order not to interrupt the work of his fellow astronauts, lending the images a slightly eerie, deserted feel—and one that forces attention on the aesthetic of the space.

Astronauts’ perspective

Nespoli explains that, when on the space station, you feel as if you have been ejected from your home planet. “You are an extra-terrestrial person. You look down, you see your planet and it's the first time you perceive that that is your home. To me, Earth felt like it was a ship flying in the universe.

“In space, when you’re flying at the orbital velocity of 8km/s, in just a couple of minutes you've flown across all of Europe. From space, you see there are no borders and that we are all on the same ship.”

It was a literal perspective that offered a unique existential perspective of its own. “Compared to the universe, we are one grain of sand among all the grains of sand on all the beaches and deserts in the world. We are a speck of nothing.”

The space station interiors

These photos suggest the space station, despite being 20 years old—and itself a victory of collaboration—still appears fairly new on the inside. “A lot of the aging process is due to scuffing and touching and shuffling around,” Nespoli says. “You don't do that in space because you’re weightless. The walls are made of painted metal, so it’s easy to keep them clean.”

He says there is more wear and tear in the Russian section of the station. “I think it’s because the Americans over-design things. I would guess the Americans studied the composition and durability of the interior spaces. The Russians are a little more pragmatic. If it’s works, it’s okay.”

In any case, as Nespoli explains, the station components are continually being cleaned, maintained and upgraded—an essential process since it’s a life support system for the astronauts living aboard.

“If the oxygen pump breaks, I can’t go to the shop to buy a new part. There is no shop. If you want something from the corner store, that's Earth, and, at best, it will take three months to get it. So NASA figured out which parts are likely to break and made sure we have critical spare parts on board.”

Constant maintenance is crucial. “I would say 30% to 40% of our time on the station is spent keeping it running,” he adds. “Every day, there are two or three hours of maintenance.”

The toilets are given special attention. “You do not want the toilet to break because not having a toilet is a major problem,” Nespoli says prosaically. “So every two or three weeks we are in the toilet, maintaining it.”

Communications with Earth

When the space station was designed, the internet was still in its infancy. Originally, for cyber security reasons, the only communication astronauts had was directly with mission control in Houston. Open internet access was seen as too risky.

“If you want astronauts on board for six months or a year, you need something to break down the isolation and confinement,” Nespoli stresses. “Make them feel they are still human beings; not robots that work 16 hours a day. So the NASA Astronaut Corps argued for getting direct internet access in space, a telephone to call any number on Earth, and exchange of data to receive fresh magazines, newspapers and movies. But the tech guys objected: ‘If you have the Internet, you will have hackers assaulting the station!’ they said. A compromise was reached by creating an additional network completely separate from the operational one that makes the station work. This allows for email, social media, and telephone calls.”

Living in zero gravity

When astronauts first arrive at the station, they struggle to adapt to the weightless atmosphere.

“You’ve been training for seven to 10 years, and you know exactly what’s there from a technical point view, but you don't know how you will feel,” says Nespoli. “This changes how your body and mind work. When you arrive there you are physically disabled. How do you move, walk, eat, sleep?

“There is a joke between astronauts: you go to space and your IQ is divided by three because you make so many mistakes. You need to re-learn everything, even simple tasks like moving, staying still, drinking. You think a certain task will take five minutes but in reality it takes up to five times longer.

“On the ground we learn to walk when we are kids and it takes some time to master this. In space, you’re back to square one. The first day, you move your center of gravity and nothing happens. You learn very quickly that pushing yourself around in zero gravity is not so simple. During the first days you’re bumping off computers, catching cables. You realise you are 90kgs of stuff flying around. If you push too quickly you end up hitting something hard.

It plays tricks… When you arrive and see one person working upside down, another person working sideways and someone else in another orientation, your brain tells you immediately: ‘This place is nuts’.Paolo Nespoli

“At first a lot of astronauts get hit by space sickness because the station is so big and you’re moving in weightlessness. There is no up and down. That's the transition between earthling and extra-terrestrial… It's a bit of a mess and it plays tricks with your brain. When you arrive and see one person working upside down, another person working sideways and someone else in another orientation, your brain tells you immediately: ‘This place is nuts’. But after a while you forget about it.”

Circadian effects

Spinning around the planet subjects astronauts to 16 sunsets every 24 hours. Inevitably this impinges on one’s body clock. However there are few windows aboard the space station (since they weaken the structure), so that astronauts have little reference to sunlight. The cupola offers the best views of the outside world.

“It was originally a bit of a fight to figure out which time zone to use. The Americans wanted to use American time and the Russians wanted to use Russian time.” Nespoli explains. “So we used Greenwich Mean Time (GMT).”

Nespoli explains the compromise of GMT. Public transport back on Earth affected the decision, too. Ground control in Russia is in Moscow, while in the United States it’s in Houston. While all Houston flight controllers drive to work, many Muscovites take the Moscow Metro, which shuts down during the night. Therefore it made sense to place Moscow controllers on day shifts and American controllers on night shifts.

(Pictures: check out Moscow's surprisingly elegant subway stations.)

“On the station, you start working at 7:30 in the morning, which makes it a perfect 9:30am start for the Russian controllers,” Nespoli adds.

He stresses how, in space, it’s very difficult to sense the passing of time with any accuracy. On some days time seems to zip by, and on others it drags. “It gives you the feeling that time is not fixed,” he says. “At 10pm [GMT] you might go to the cupola, open the shades and look outside to find it's the middle of the day. Or you go there during the day and you think ‘We’ve got a gorgeous pass over London, let’s take a peek’. You open the shades to find it’s night in London; you feel this blackness coming at you. It’s so strange.”

Time for bed

Most days, astronauts work from 7.30am to 7.30pm, retiring to bed before 11pm. Each has his or her own sleeping quarters.

“It’s similar to a telephone booth, with a door you can open and close,” Nespoli explains. “That's your only personal place on the station. Inside you keep your computers, your pictures, your spare clothes and a sleeping bag. Actually, it’s a bag without down, so it’s more of a sleeping cocoon.”

Some astronauts choose to strap themselves in tightly while they sleep, while others prefer to float a little. Some lie face up, others face down.

“At night, when you try to go to sleep and you close your eyes, you feel as if you are falling,” says Nespoli. “For some people it’s very difficult to sleep. I personally like the floating part. I put my sleeping bag on loosely. I turn the lights off, and I cover the various LEDs with sticky tape, so it’s pitch dark. You can regulate the temperature and the flow of air. It was one of the best sleeps I’ve ever had.”

Time to eat

Nespoli says most astronauts eat breakfast alone, and many grab a quick snack from the cafeteria for lunch. Dinner times tend to be more sociable, depending on the national configuration of the crew. Often there will be three Russians, two Americans and either a single European or a single Japanese aboard.

“On Friday nights the Russians invited us to have dinner with them,” Nespoli remembers. “We reciprocated on the Saturday. On Sunday nights we all had a meal and a movie together.”

Alcoholic drinks are not permitted aboard the station. “It’s a little bit cultural,” Nespoli explains. “The Americans have all these laws about alcohol in government facilities. As an Italian, I wouldn't see any problem in having some alcohol on board; I think a glass of wine would make dinner much nicer. Of course we don’t want to have anybody drunk on the station.”

Preparing food is of course much more complicated than on Earth. “You can’t boil water and there’s no microwave,” Nespoli explains. “But there is an induction system, so you can warm up metallic plates. And of course all the food is pre-packaged.”

It’s hardly cordon bleu cooking, though. “NASA looks at astronauts like they are machines. What does that machine need to work? Oxygen, water, food. Food is just fuel. Calories, vitamins, proteins. The smell, taste and appearance are secondary.”

A while back, however, the astronauts complained about the monotony of the food on offer. So NASA offered what they called “bonus food”, allowing crew to choose extra items beyond the standard menu. Nespoli says they now permit around 25% of the food to be selected from what’s commercially available in shops on Earth – as long as it has passed the various food standards tests. Nespoli’s bonus food included lasagne, fish and Italian desserts. “Once a month I would invite everybody to an Italian dinner,” he remembers. “It was all part of building a crew.”

The food he missed most of all, however, was pizza. “I remember looking down at clouds on Earth and seeing pizzas in the clouds. My brain was giving me a message, showing me what I was missing.”

During his final mission, while talking to a group of schoolchildren back on Earth, the subject of pizza came up. By coincidence, the father of one of the schoolchildren was the space station’s programme manager.

“When the next [supply] spacecraft arrived, I got a message from Houston, telling me there was a special package for me,” Nespoli remembers. “Inside were all the ingredients to make a pizza in space.”

The future of humanity in space

In the distant future, when humans finally leave Earth, they may live aboard space stations as well as on other planets.

Nespoli concedes that he believes habitable exoplanets beyond our solar system might prove to be very rare. “Earth is almost a fluke of nature,” he says. “But there are plenty of flukes of nature. There are many planets that could be similar to Earth, but they are a number of light years away; impossible to reach with today’s technology.”

(Related: Find out about the exoplanets we know of.)

That shouldn’t put us off dreaming of life beyond our planet, he insists. This is a concept he explains when he visits schools to talk to children about space. Often his presentations will conclude with the three exhortations:

“First I tell them: ‘The future is yours’,” he says. “This means they must take control of their futures. Then I tell them: ‘Dream impossible things’. Much better to dream impossible things than things that are already possible. Finally, I tell them: ‘Wake up and start working on it’. Because if you dream but you don't act on it, then you won't go anywhere.”

This story was adapted from the National Geographic U.K. website.