This dish towel ended the Civil War

“It is sufficiently humiliating to have had to carry it and exhibit it,” fumed the Confederate officer who wielded the flag of truce—now on display at the Smithsonian—at Appomattox Courthouse.

With Union troops surrounding his Confederate Army in Appomattox, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, Gen. Robert E. Lee decided he had no choice but to initiate surrender talks. He sent a staff officer across enemy lines to ask for a cease-fire until he could meet with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. To pass safely, Confederate officer Capt. R. M. Sims carried a fringed white dish towel with three thin red stripes running across the bottom.

Today, half of that towel—known as the Confederate flag of truce—sits inside a glass case on the third floor of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, on display as part of “The American Presidency” exhibit. Now yellowed with age, this often-overlooked artifact played a key role in one of the most pivotal moments in our nation’s history. “It’s a national treasure,” says James Ferrigan, a consulting vexillologist and an officer of the North American Vexillological Association, a nonprofit dedicated to the study of flags. “It’s the flag that began the discussion that ended the bloodiest conflict in American history.”

Flag of truce—a monument of defeat?

In April 1865, the flag paved the way for a cordial meeting between Lee and Grant. Five days later, John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. Fighting between the North and the South dragged on for another year and a half, until President Andrew Johnson formally declared the end of the conflict in August 1866, but many consider the surrender at Appomattox Court House to be the Civil War’s de facto conclusion.

Much to Sims’ chagrin, the flag of truce ended up in Union hands. “(Union) Colonel Whitaker asked me if I would give him the towel to preserve that I had used as a flag. I replied: "I will see you in hell first; it is sufficiently humiliating to have had to carry it and exhibit it, and I shall not let you preserve it as a monument of our defeat," Sims wrote in a May 1886 letter describing his role in the surrender.

After the war, Gen. Philip Sheridan presented the flag of truce to Gen. George Custer’s wife, Elizabeth, “in appreciation of the loyal service performed by her husband.” Upon her death, she bequeathed it to the United States National Museum, the precursor to the national museums we have today. It’s been part of the national collection since 1936. (Somewhere along the way, the flag was cut in half—and the location of that missing piece remains a mystery.)

“No army in the world issues this flag”

Why a dish towel? Throughout history, flags of truce—also known as flags of parley—were nearly always household items like towels, sheets, and pillowcases.

“No army in the world issues this flag because it’s counterproductive to morale,” says Ferrigan. “And, so, if things aren’t going your way and you have to go chat with the guy with the bigger guns and more guys, well, then, you have to find something.”

For museum-goers, the flag of truce likely holds different meanings depending upon their political beliefs, upbringing, family history, life experiences, and identity, says Lisa Kathleen Graddy, the curator in the museum’s political history division who put together “The American Presidency.” And, though the surrender occurred nearly 160 years ago, the flag’s symbolism continues to evolve over time. “The amazing thing about objects is they come to carry, physically and metaphorically, the emotions and importance of a moment, which is why we save them,” she says. “But the interpretation depends on who’s looking at it: It could be seen as a moment of bitterness, or a moment of victory.”

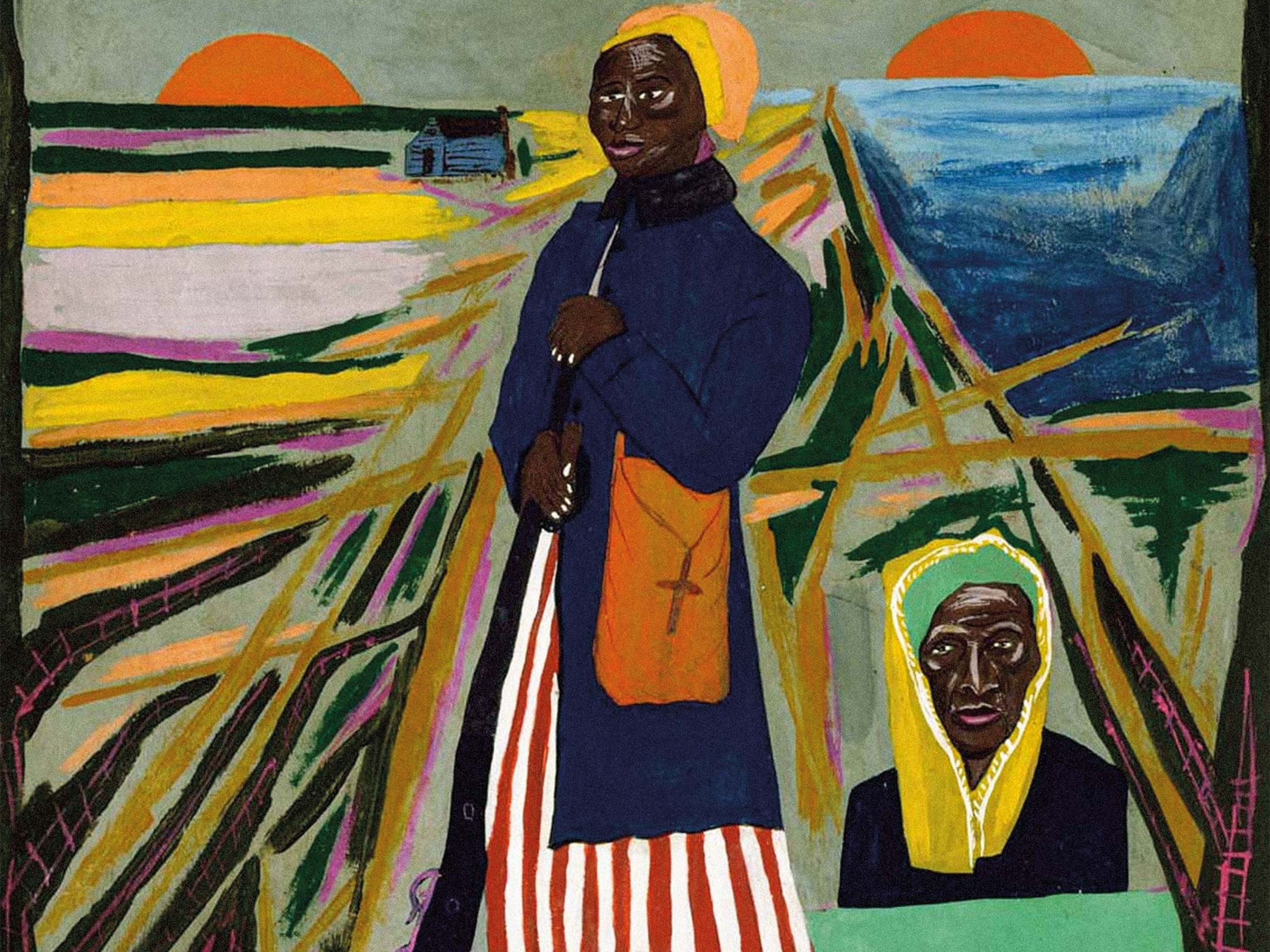

The same is true for another, better-known remnant of the Civil War: the Confederate battle flag. While the flag of truce remains largely unknown, the Confederate battle flag has become an enduring—and ubiquitous—symbol of racism, appearing on everything from baby onesies to key chains. Artist Sonya Clark, a professor of art and art history at Amherst College, explored the flags’ contrasting legacies in her 2019 exhibit “Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know,” held at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. With that show, she asked viewers to imagine a world in which the peace-brokering flag of truce—instead of the divisive Confederate battle flag—dominated the American narrative.

Four years later—as George Floyd's death sparked a U.S. reckoning on race and white supremacists continue to threaten democracy—Clark’s feelings about the flag of truce’s meaning have only gotten more complex. “What progress have we made?” she asks. “Really, what was surrendered?”