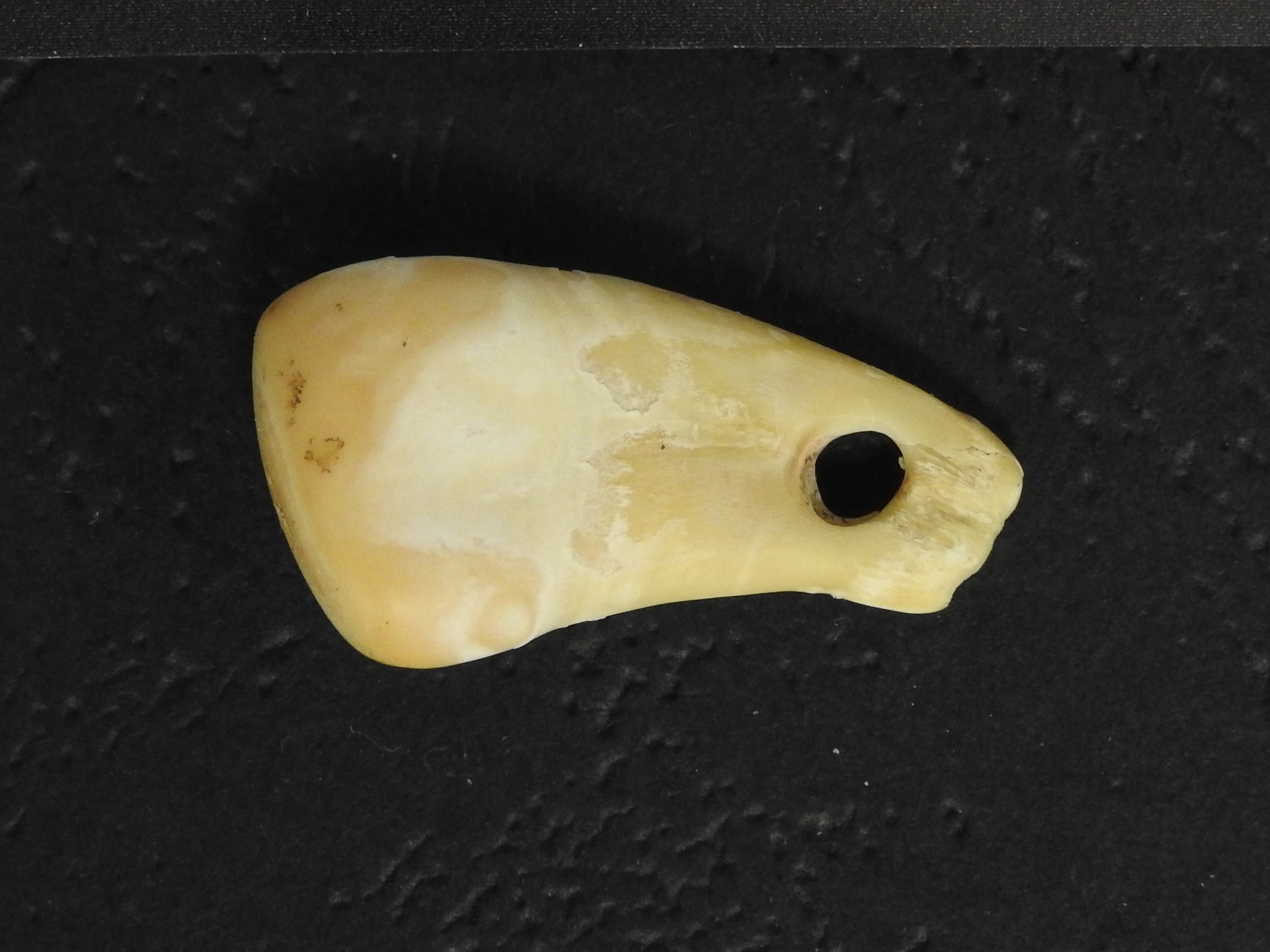

Who wore this pendant 20,000 years ago? DNA can now tell us

A breakthrough technique extracts human DNA from bone artifacts, offering scientists an unrivaled look at the individual owners or creators of objects from the deep past.

Ancient DNA has transformed archaeology: It’s now possible to determine the sex and ancestry of ancient humans by amplifying the coded genetic material that survives in their remains. Ancient DNA studies now span hundreds of thousands of years, and offer new understanding on events in the deep past, like the migrations of the first Americans and where the Neanderthals went.

Now a new study published in the journal Nature reports that scientists have extracted human DNA from a deer-tooth pendant likely worn by a woman about 20,000 years ago. This is the first time ancient human DNA has been recovered from an artifact made from another animal, and researchers hope the breakthrough method will also be used in the future to reveal critical information such as which hominin species made a particular bone tool, for example, or how ancient humans divided tasks between sexes, such as sewing hides or making bone spear points. This new DNA extraction technique can also date bone artifacts without damaging them—an advantage over radiocarbon dating, which destroys a small sample of the material.

“This is a proof of principle study,” says a study senior author, geneticist Matthias Meyer at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. “It will take some time until this translates into new insights… but it will be huge.”

Paleolithic pendant

Meyer and his colleagues studied a pendant made from a deer tooth found in Siberia’s Denisova cave in 2021. The cave was occupied by different hominin groups for about 50,000 years and became famous in 2010 with the discovery there of a previously unknown human species called Denisovans. The pendant, however, comes from a sediment layer about 20,000 years old, when the cave was inhabited by Homo sapiens. It’s not been possible before now to extract ancient human DNA from such an artifact; usually a sample would be drilled from the tooth and ground up, hopefully revealing the DNA of the deer it came from. But the new technique, which involves washing the artifact in a sodium phosphate solution, has recovered both sets of ancient DNA—from the deer as well as the human who made or wore it—and without damaging the pendant.

Molecular biologist Elena Essel, the study’s lead author and a doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, says the researchers tried different chemicals until they hit on using sodium phosphate, which is also used in washing powders for clothes.

The method of extracting DNA is also similar to doing laundry: the pendant was bathed in a fresh batch of the solution several times, at increasing temperatures up to almost 200 degrees Fahrenheit.

The researchers used their knowledge of human and deer genetics to distinguish one (Homo sapiens) from the other (wapiti, a type of elk), and to determine both the sex and ancestry of the human, showing she descended from ancient North Eurasians, an ancient population that until now has only been recorded further east.

The researchers also dated the pendant by calculating the number of mutations in the ancient DNA and comparing them to modern genomes. Both the deer and the human DNA yielded a date of between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago, which is a larger time range than that provided by radiocarbon dating (which can provide dates to within a few decades in some cases) but was done without damaging the pendant—while the radiocarbon method would, Essel says.

Archaeological advance

Archaeologist Marie Soressi of Leiden University in the Netherlands, a senior author of the paper, says bone artifacts are not as common to find as stone artifacts in prehistoric archaeological sites, perhaps because they often decay over time. But there are still many, including bone figurines, sewing needles, tools for knapping flints, and bone spear points and arrowheads. “For the first time we can make a correlation between a specific [bone] object and a specific individual, according to the biological sex of the individual or ancestry,” she says.

As well as revealing if sewing or making art was done mainly by one sex or the other, the technique might also determine whether Neanderthals or Homo sapiens made bone artifacts found at locations where both species lived, she says.

The researchers are still studying how long a bone artifact needs to be handled for it to absorb human DNA. Soressi says the pendant was probably worn next to the skin for months or years. But the human DNA might also come from the person who made the pendant and handled it for a relatively short time.

Geneticist Kendra Sirak at Harvard University’s Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, who wasn’t involved in the study, notes the new non-destructive method of extracting ancient DNA will preserve delicate bone artifacts for archaeologists who may have different analytical techniques. “The great thing about this technique is that it keeps the integrity of an artifact, which means that other people can perform different types of studies on it,” she says.

Soressi says archaeologists who hope to use the new technique will need to take special measures when first excavating the artifact to avoid contaminating any ancient DNA with modern genetic material, such as wearing gloves and masks while digging and quickly enclosing artifacts in plastic bags: “It will require a change in routine.”

The technique will also require even more cooperation between the archaeologists who excavate suitable artifacts and the geneticists who will test them. But archaeologists and geneticists already discuss how to maximize the chances of recovering ancient DNA before a shovel or trowel is put in the ground, Sirak says: “We’re now not thinking about DNA as something that’s done only after the fact.”