Should you get tested for a BRCA gene mutation? It’s complicated.

Certain genetic mutations can boost your risk of breast cancer. Here’s what experts say you need to know when making the decision to get tested.

A woman with a family history of breast cancer may wonder if she carries an inherited genetic mutation that increases her risk for the disease. To find out she could take a genetic test to see if she carries certain gene mutations, which boost the chance of breast and ovarian cancer. But she isn’t likely to get the clear-cut answer she is seeking.

“Gene mutations account for about 5 to 10 percent of cases of breast cancer,” says Claudine Isaacs, a medical oncologist and co-director of the Fisher Center for Hereditary Cancer and Clinical Genomics Research at Georgetown University. “Most people who have a family history of breast cancer do not carry a genetic mutation” that significantly elevates their risk of breast cancer.

It could be that breast cancer simply runs in a woman's family—like diabetes or high blood pressure—even if she doesn’t carry a single high-risk gene mutation. “Even if women test negative for genetic mutations, it doesn’t mean they’re not at risk for breast cancer—they’re at higher risk simply because they have a family history of breast cancer,” explains Carrie Costantini, a breast medical oncologist with the Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center and a physician with the Scripps Clinic in San Diego. It may be that a woman carries dozens or hundreds of gene variants that each boost her chance of developing the disease just a little, or that her increased risk is due to lifestyle factors she shares with family members.

So while finding out that you don’t carry a high-risk gene mutation may be reassuring, it doesn’t mean you’re off-the-hook as far as breast cancer goes. On the other hand, the presence of a problematic genetic mutation doesn’t guarantee that you’ll get breast cancer, either. This is a complex issue.

An expanding picture of gene mutations

Mutations in the genes known as BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the best-known ones that influence breast cancer risk, but they’re not the only ones. Mutations in other genes, including ATM, CHEK2, PALB2, and TP53, are also associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and other forms of cancer.

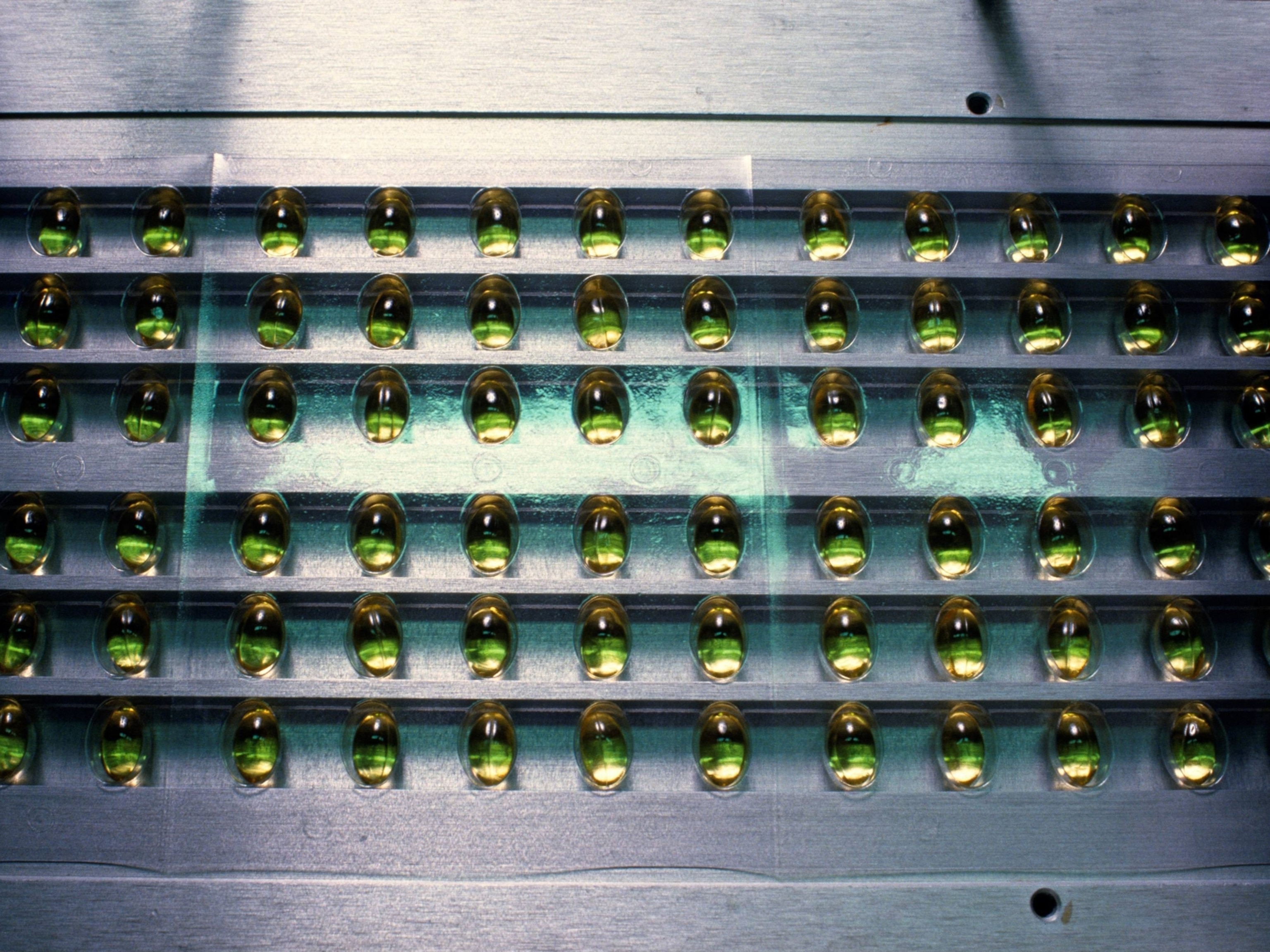

That’s why genetic testing for breast cancer risk is now done with a test that screens for mutations in multiple genes. The actual test uses a blood sample, a saliva sample, or a swab of cells taken from the inside of the cheek, then the sample is sent to a lab to test for mutations.

Although the extent to which different gene mutations increase a woman’s risk of breast cancer isn’t completely understood, it is known that BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations carry the highest risk. In a study in a 2017 issue of JAMA, researchers evaluated the risk of breast and ovarian cancer over time among 9,856 women who carry one of these mutations: The cumulative risk of developing breast cancer by the age of 80 was 72 percent for BRCA1 carriers and 69 percent for BRCA2 carriers; the women’s family history of cancer and the location of the mutation in the gene were found to be important variables in determining risk.

“People sometimes view having a gene mutation as being a big red box, as being a diagnosis, and a diagnosis requires an intervention,” says Mark Robson, a medical oncologist and chief of the breast medicine service at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York City. Carrying a high-risk gene mutation for breast cancer is a risk factor, not a diagnosis. “That’s the problem with doing [genetic] testing for everybody,” Robson says, referring to the fact that it’s not easy to know what to do with the results.

To test or not to test . . .

It’s widely agreed that women who have or have had breast cancer should undergo genetic testing to see if they carry a high-risk mutation because it impacts treatment and, potentially, outcome, Isaacs says.

Women who haven’t had breast cancer but have a strong family history of ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, or breast cancer—especially premenopausal breast cancer or male breast cancer—should consider getting a genetic test, Robson says. This is especially true if these cancers have affected multiple first- or second-degree relatives, says Leigha Senter, a genetic counselor and professor of internal medicine at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center in Columbus.

When you review your family history of breast cancer, it’s important to consider both your mother’s and father’s side. Consider your ethnic heritage, too: Women of Ashkenazi Jewish descent have a higher likelihood of having a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, so they should consider genetic testing, experts say.

Ashley Dedmon opted for genetic testing after her father was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2007 and her mother died from breast cancer that same year. (Her grandmother and great grandmother also had had breast cancer.) “Losing my mother was the defining moment,” says Dedmon, who was then in college. “I’m a Black woman, and it was very important to me to find doctors who understood my risks as a Black woman. Genetic testing changed the blueprint of my standard of care.”

In deciding whether to undergo genetic testing for breast cancer risk, some women hope it will help them feel empowered because they’ll at least know what they’re dealing with, while others worry that it will create unnecessary anxiety. “Some people tell me they don’t want to live their life wondering what could happen,” Costantini says, which is why they don’t want to get tested.

Victoria Simo, a former professional ballet dancer, has a family history of breast cancer and when she was 29, her ob-gyn found a lump in her left breast. A biopsy revealed that it was benign but waiting for the results ratcheted up her anxiety significantly. At age 37, Simo found a lump in her right breast, which was difficult to biopsy because it was close to the chest wall. That’s when she decided to have genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations.

The prospect of developing breast cancer is fraught with anxiety for many women, and the same is true when it comes to genetic testing for high-risk mutations. In fact, a study in a 2017 issue of the journal Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice found that 21 percent of women who had testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations developed anxiety a month after the results were delivered—and this was true even among women with a negative result.

That’s why many experts believe testing for high-risk gene mutations should be considered in the context of genetic counseling. But if a woman learns she carries a gene mutation without having had genetic counseling, she should see a counselor at that point, to discuss what the positive finding means and how to tell family members, Isaacs says.

After all, other people in the family could have the same mutation. “This kind of testing impacts families, not just the person who is having the testing,” Senter notes.

What to do after getting test results

Undergoing genetic testing for breast cancer risk “used to feel like a crystal ball you could look at but you couldn’t do anything about it,” Isaacs says. That has changed significantly.

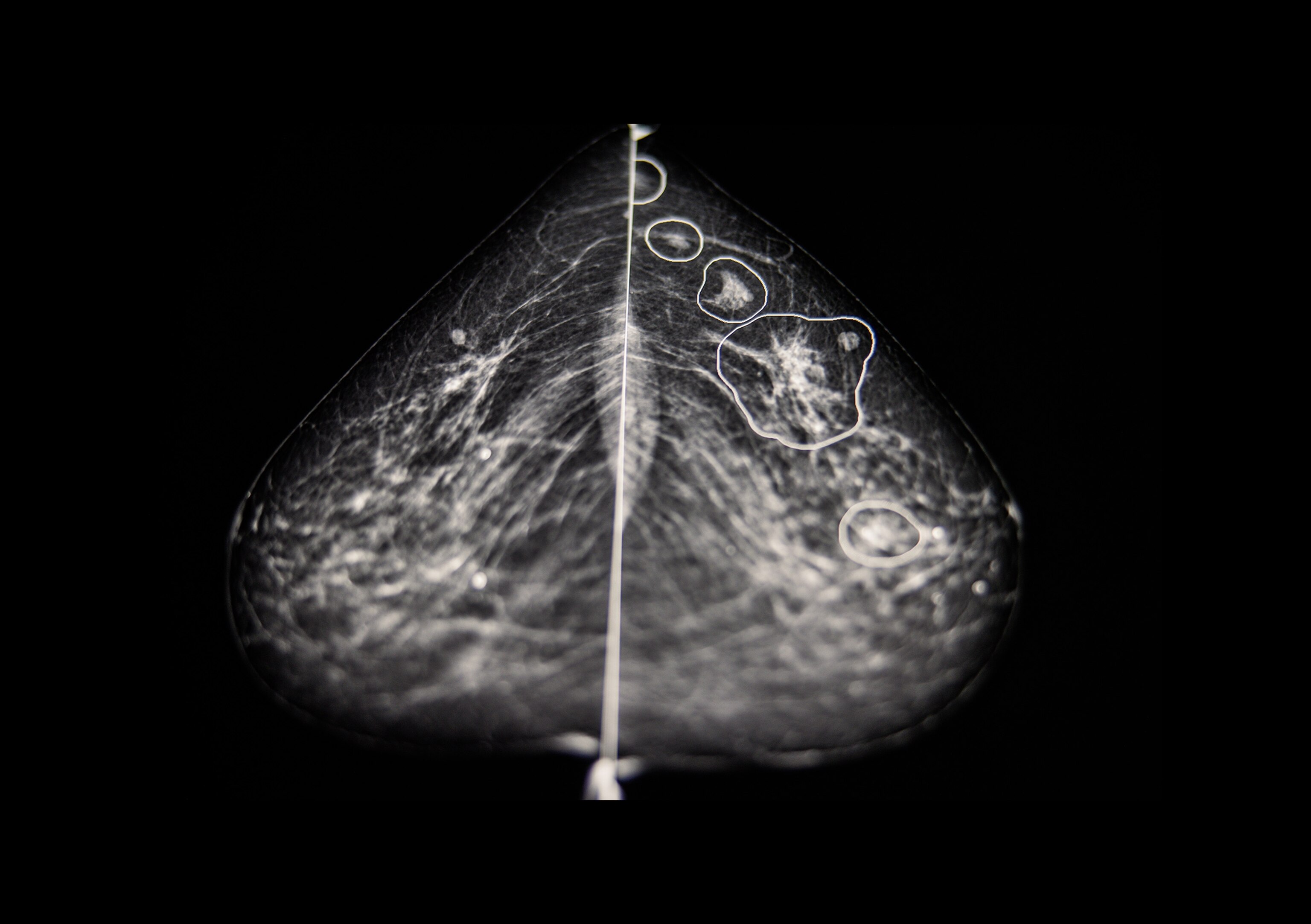

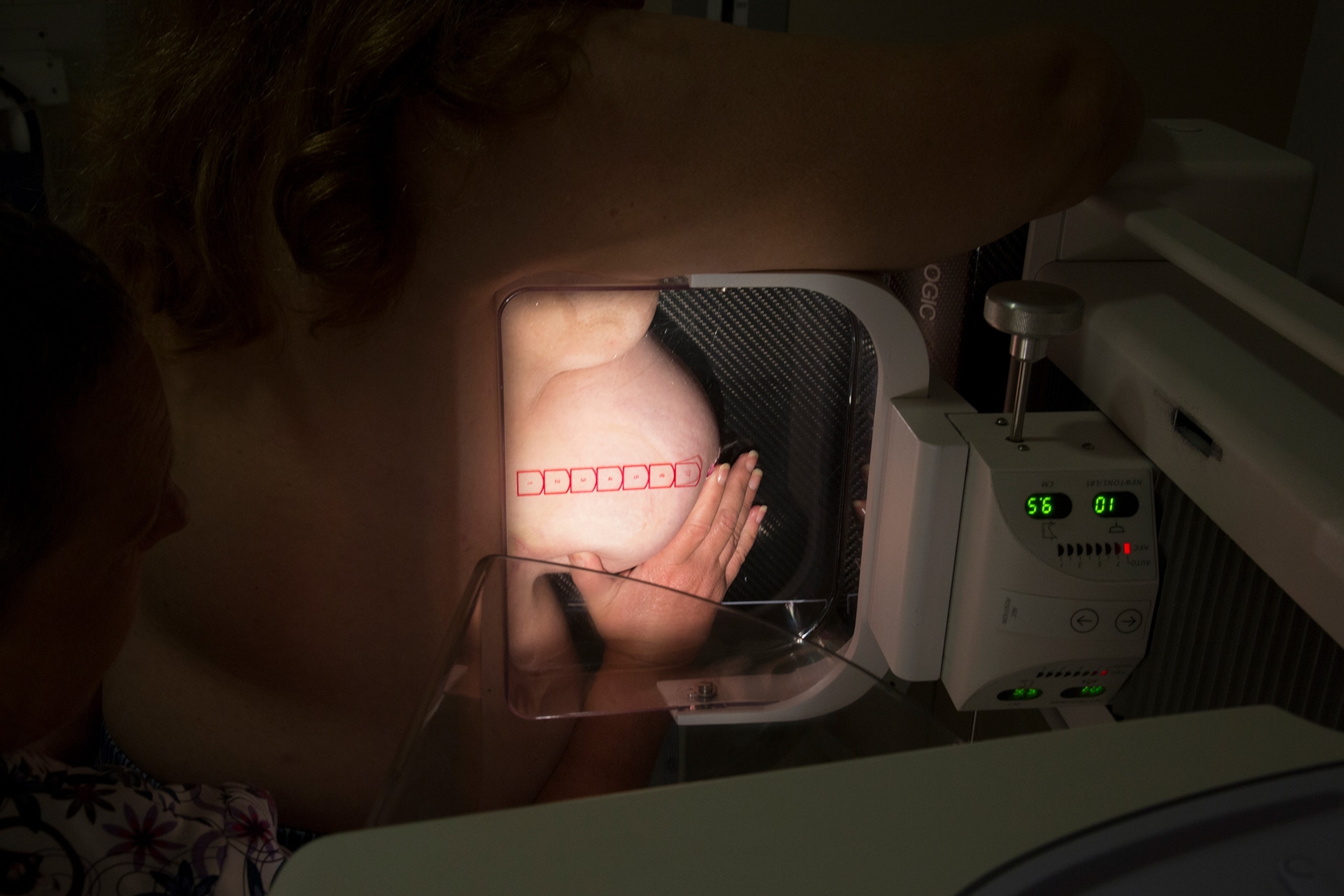

Now, there are clear guidelines for intensive screening (a.k.a., enhanced surveillance), often involving more frequent breast exams by a medical professional and mammograms plus breast MRI for women with a positive result. The goal is to try to detect cancer in the earliest stages if it does occur.

There are also various preventive measures women can take. These include having a prophylactic mastectomy—surgery to remove the breasts, as actress Angelina Jolie famously did in 2013 after discovering that she inherited the BRCA1 mutation. Another option: surgical removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes (formally known as salpingo-oophorectomy) by age 40, has been found to reduce breast cancer risk in women who carry a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, according to research published in a 2021 issue of JAMA Oncology.

In November of 2019, Simo, the ballet dancer, learned she carried a BRCA2 mutation and opted to have a hysterectomy and double mastectomy in February of 2020. “I was very lucky because I had a doctor who encouraged me to have this testing. It has changed my life for the better,” says Simo, now 40, a mother of two children and owner of a ballet and Pilates studio in Houston. “I wouldn’t have known I had a ticking timebomb inside me.” Simo chose to go flat rather than have breast reconstruction surgery.

After discovering she carries a BRCA2 mutation, Dedmon at first opted for increased surveillance and had her first mammogram at age 21. After getting married and having her first child, she had a preventive double mastectomy, followed by breast reconstruction at 31. “As I became a wife and mother, I wanted an option that would drastically reduce my risk without my having to go to the doctor every six months,” says Dedmon, now 37, who is a mother of two daughters and works for a nonprofit in Houston. “When I woke up from the surgery, I felt a tremendous sense of relief and knew I had made the best decision for me and my family.”

On the less invasive side, chemopreventive agents—drugs that are used to reduce the risk of cancer—are being developed. Already, tamoxifen, an anti-estrogen medication, is sometimes used to reduce the risk of breast cancer in women with BRCA2 mutations; research suggests tamoxifen can reduce breast cancer incidence by 62 percent in healthy women who carry BRCA2 mutations. And studies are underway to look at whether denosumab, a monoclonal antibody that’s used to treat bone loss, could reduce the risk of breast cancer in women with BRCA1 mutations. “We’re trying hard to find ways to minimize risk in as unaggressive a way as possible,” Isaacs says.

In addition, a woman with a high-risk gene mutation can take steps to improve her lifestyle—by getting regular physical activity and managing her weight—which may reduce her breast cancer risk, Isaacs says. A study in a 2020 issue of the journal Cancer Research found that women who engage in regular exercise have a 20 percent lower risk of breast cancer, even if they carry a BRCA mutation.

The final analysis

Figuring out what to do with a positive result from genetic testing is a personal decision. A study in a 2022 issue of the journal Cancers found that women who carry BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations considered lifestyle factors like childbearing status, their age and stage in life, and their feelings of vulnerability, among other factors, when deciding whether to have risk-reducing surgery.

“I’ve seen women feel pushed towards a decision [about prophylactic mastectomy] they don’t necessarily want to make—there’s social pressure that takes place,” Robson says. “People should know what they’re getting into.”

This is yet another reason it’s important to consider what you might do with the information before you have the testing, Costantini notes. “It can be emotional to get that result, even if you wanted to know.”