Is ‘leaky gut’ real? It’s more complicated than you’d think.

Dubious claims are out there of leaky gut causing diseases from depression to autoimmune disorders. Experts weighed in on why that may not be the case.

Numerous websites have issued warnings about a condition called “leaky gut,” claiming that it can cause depression, anxiety, autoimmune disorders such as chronic fatigue, eczema, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, joint pain, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and other disorders.

But is it real? And, if so, is it dangerous? And can you prevent it?

The condition is real, but physicians and scientists call it “intestinal hyperpermeability”—and so far, the research does not show that it’s the cause of all those conditions. Instead, the opposite appears to be true. Various health conditions can cause the intestine to become more porous and release more harmful substances that it should.

“It’s a myth that all these diseases start with a leaky gut,” explains Michael Camilleri, a gastroenterologist and professor at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science in Rochester, Minnesota. “What we do know is that certain diseases cause intestinal hyperpermeability,” he says. Examples are celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease, obesity, intestinal damage from using NSAIDS (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications), among others.

One of these diseases, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), is the most commonly diagnosed digestive disorder, striking between 6 percent and 15 percent of American adults. Along with abdominal pain and bloating this disorder causes chronically abnormal bowel movements. A Mayo Clinic review found that up to 62 percent of people with diarrhea-prone IBS and up to 25 percent with the mainly constipation-type had intestinal hyperpermeability.

“But it remains unknown whether hyperpermeability is a cause of IBS,” Andrea Shin, a gastroenterologist and an associate clinical professor at the University of California Los Angeles Geffen School of Medicine, wrote in an email.

A little leakiness is good, a lot is not

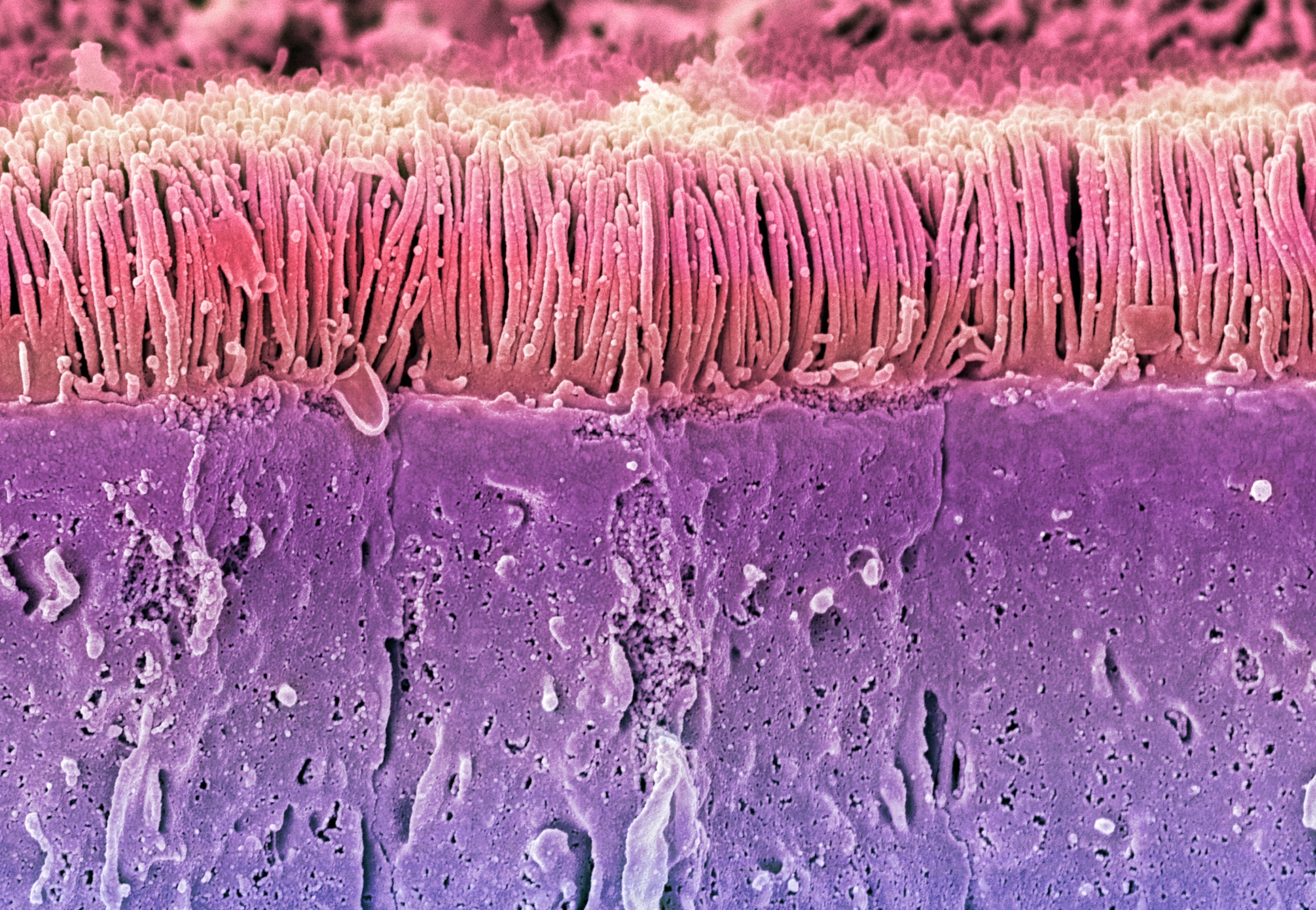

To understand leaky gut, it helps to understand your GI tract’s life-or-death function: Bring nutrients into the body and keep out the bad stuff.

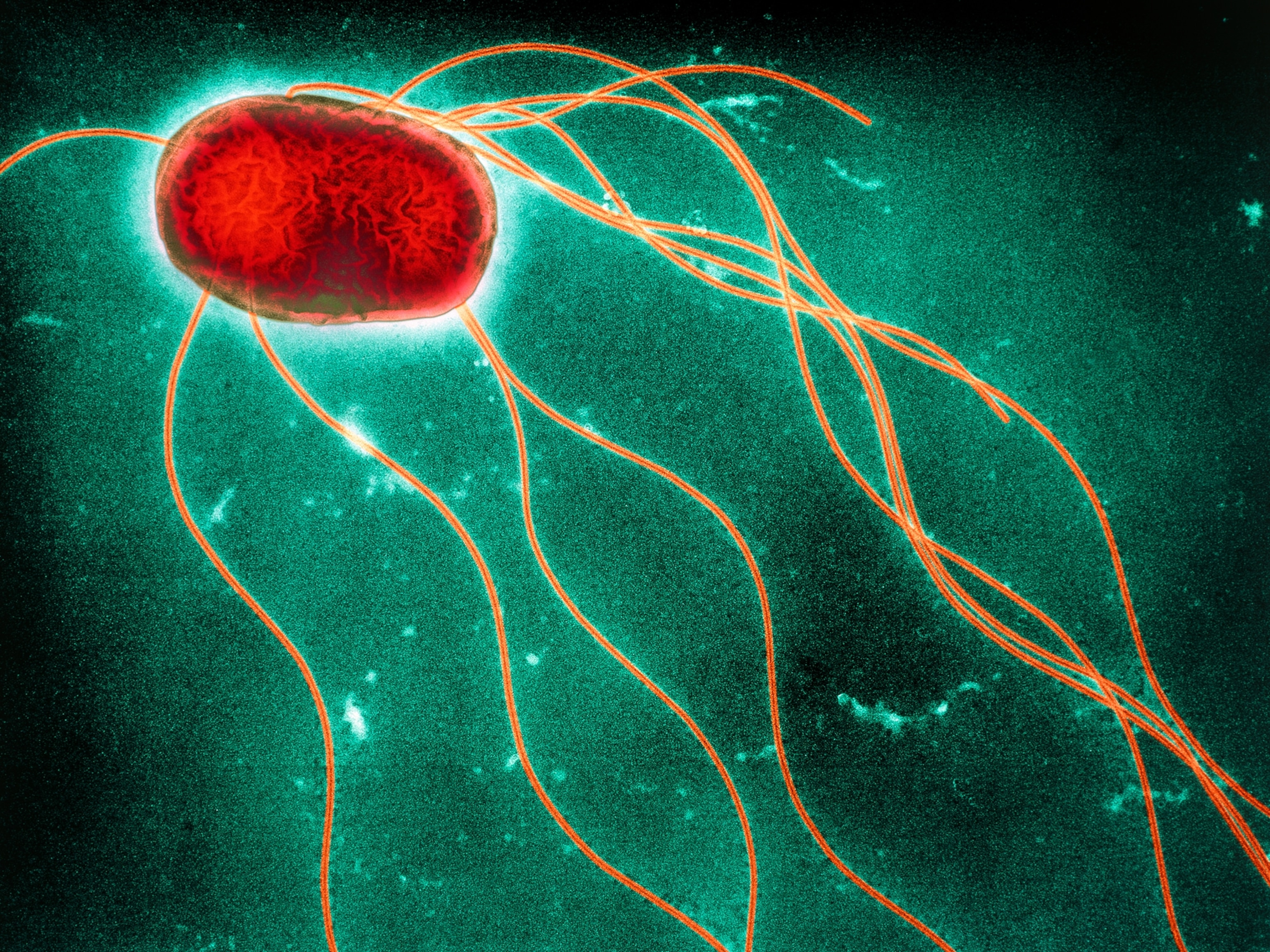

To do this, “the intestinal tract needs to be at least a little porous and permeable. It must allow the absorption of water and nutrients from digested food such as sodium, and small molecules such as glucose,” Camilleri says. After nutrients are absorbed into intestinal cells they migrate into the bloodstream and nourish the rest of the body.

To perform this absorption trick, specialized cells lining the intestine have semi-permeable walls. And even though they stand shoulder to shoulder, locked together with so called “tight junctions,” there’s still a little space for small molecules to slip through. That’s normal. Tight junction proteins are the glue that holds the cells together.

“But if the junctions loosen and the intestinal tract becomes too permeable—your health is at risk because substances that shouldn’t have access, such as not-completely-digested protein, or bacteria, get through. These can pass into your general circulation and, conceivably, damage organs,” Camilleri says.

No one’s quibbling over whether intestinal hyperpermeability is dangerous—it is. But where the medical establishment splits from some in the wellness industry is the cause, the diagnosis, and the treatment.

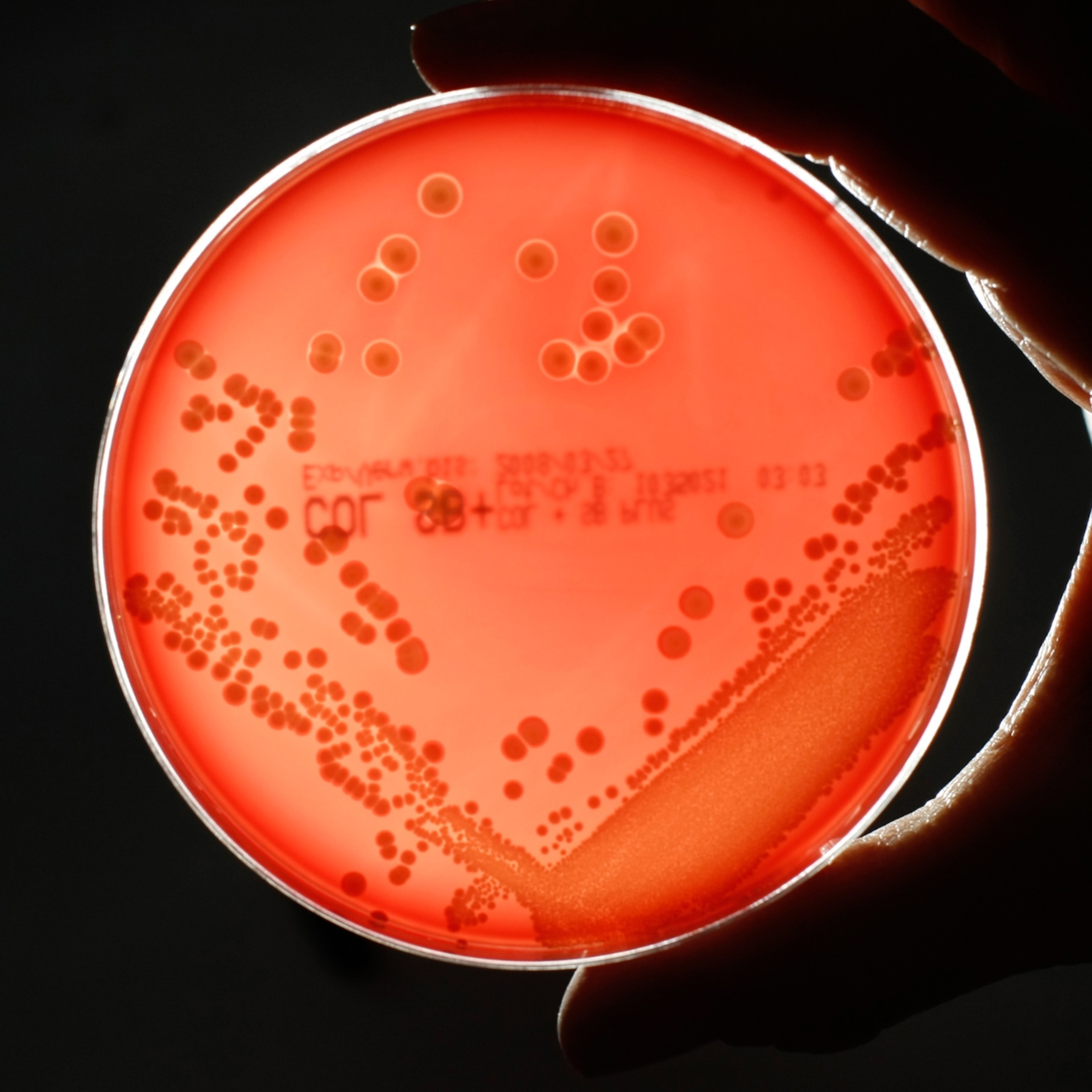

Testing for intestinal hyperpermeability

So how do you know if you have an abnormally leaky gut? Experts are dubious about test kits on the web.

“There isn’t a well-established non-invasive test that is scientifically and clinically valid. That’s why most intestinal permeability research has been conducted in animal and cell culture studies—scientists can more carefully study the gut and its function that way,” says Hannah D. Holscher, a dietitian and associate professor of nutrition at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Shin concurs: “My patients ask if they can be tested for “leaky gut”, and I tell them that although different tools and methods are used in research, there is still no clear gold standard.”

“I don’t know of any commercially-available gut test kits that will diagnose leaky gut,” Mayo Clinic’s Camilleri says. However, he and his colleagues may have developed a diagnostic test that may soon be available. (He declares he has no financial interest in the new test.) It involves drinking liquid spiked with specific types of sugars, then collecting urine throughout the day to see how much is excreted. The more of these sugars that wind up in the urine, the more permeable the gut. Not exactly an easy test, but it’s proven to be accurate.

The diet/gut permeability connection

There is scant data revealing specific lifestyle factors that contribute to a dangerously leaky gut. But emerging research does indicate that diet can affect gut permeability in many ways. Here are a few:

Dietary fiber (fiber). Fiber-rich foods including fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains help prevent constipation and maintain the mucus layer in the intestines, a defensive barrier that helps keep bacteria and other harmful substances from infiltrating intestinal cells and degrading the tight junctions between them.

“We have trillions of microorganisms in our GI tract; many of them use fiber from our diet for fuel. Without enough fiber some of these bacteria feed off the mucus layer, thinning it, so it’s no longer as protective. That could lead to increased gut permeability,” explains Holscher.

Diets high in fiber also expand populations of gut bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids—which serve double-duty as healthy fuel for intestinal cells, and decrease inflammation, which is key for preserving healthy intestinal cells and their tight junctions.

Dietary fat. Nuts, seeds, seafood, and olive oil—staples of a Mediterranean diet—are rich in unsaturated “good” fat, that help decrease inflammation, while lowering blood cholesterol and possibly the risk of chronic diseases.

(Read more about why The Mediterranean diet has stood the test of time.)

But foods high in saturated fat—butter, chicken skin, coconut oil, cream, and fatty meats—which are common in American diets do the opposite.

“Eating too much saturated fat increases populations of gut microbes that can loosen tight junctions,” says Holscher.

Diets high in saturated fat encourage the growth of microbes with certain types of lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) embedded in their cell walls. Immune cells in the gut attack these microbes, releasing LPSs which are toxic to the gut making it more permeable. Even worse: LPSs can slip through the now not-so-tight junctions and into the bloodstream leading to inflammation and other complications: diabetes, atherosclerosis (narrowed arteries leading to the heart) and other chronic diseases. Unsaturated fat has the opposite effect, reducing LPSs.

Topping off their diets with just 1.5 ounces of walnuts daily for three weeks led to more anti-inflammatory gut microbes and fewer of the inflammatory bacteria in 18 men and women in Holscher’s research.

“Walnuts are rich in unsaturated fat, fiber, and phytonutrients—which act in different ways to promote gut health,” she says. Her lab is now conducting a similar experiment with avocados.

(Read about why olive oil is the healthiest of cooking fats.)

Alcohol. Like saturated fat, alcohol encourages the growth of LPS-containing gut microbes. Both chronic alcohol abuse or even just a single binge, can directly damage cells and loosens tight junctions.

Polyphenols. Fruits, vegetables, herbs, legumes, and whole grains offer many phytonutrients—compounds in plants that are antioxidants and anti-inflammatory—and help prevent disease. One main type—polyphenols—has been shown to ramp up production of tight junction proteins, thus preventing excessive leakiness.

Supplements. Experts interviewed for this story were skeptical that there were specific supplements that fix leaky gut—as some manufacturers claim. They cited just a few supplements that normalize the permeability of the gut.

Preliminary research suggests that glutamine supplements may help restore normal permeability in people with IBS.

“Glutamine is an amino acid that is a main source of fuel for intestinal cells that absorb nutrients and also for immune cells in the gut. A shortage of glutamine may cause these cells to shrink or lead to a reduction in tight junction proteins. The result: Increased intestinal permeability,” explains Shin.

Shin cautions that larger studies must be completed before glutamine is prescribed as a standard treatment and it hasn’t yet been studied as a preventative agent.

“There’s also evidence that supplementing with vitamin D, short-chain fatty acids, and fiber may also be important for maintaining and improving the intestinal barrier,” says Shin

Until there is more known about intestinal hyperpermeability—both causes and treatments—it’s best to skip the websites and hit the produce aisle for a safe and delicious approach to gut health: The Mediterranean diet.