Hawaii's māhū—and their ancient history—are finally re-embraced

The restored history of a Native Hawaiian monument elevates part of the rich, sacred story of māhū—those who are of dual male and female spirit–and whose powerful roles in Hawaiian culture are still present today.

Oahu, Hawaii — Tucked behind a fence and vibrant naupaka shrubs on a Waikīkī beach sit ancient boulders that honor four healers who once brought their curative powers and wisdom to the people of Hawaiʻi.

The stones have been gaining more attention recently due to the recovery of an obscured part of history: the healers were neither kāne (male) nor wahine (female)—they were māhū, a mixture of both in mind, heart, and spirit.

The healers—Kapaemāhū, Kahaloa, Kinohi, and Kapuni—voyaged from the Tahitian Island of Raiatea more than 500 years ago and became well-known across the Hawaiian islands as they used holistic remedies to cure those who were ill.

When it was time for them to leave, they requested that the stones be placed near the sea, where they imbued them with their spiritual powers.

For centuries, māhū were celebrated in Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) culture and revered not just as healers, but beloved caretakers, and teachers who passed down intergenerational knowledge. After the arrival of Christian missionaries in the 1800s, many Hawaiian cultural practices were banned, including māhū traditions and history.

Eventually the stones were buried under the foundations of a bowling alley in the changing landscape of Waikīkī and although they’ve been restored a few times since 1963, the signage has never reflected that the healers were māhū.

Now, after years of effort to reclaim the pride and Indigenous legacy of what it means to be māhū, county officials have confirmed additional signage will finally be installed to reflect the healers’ full identities.

Forgotten document emerges

Cultural leader, Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu, who has been one of the most prominent faces of māhū and transgender visibility for the last two decades, found the first written account of the stones in a forgotten box at University of Hawaiʻi Mānoa in 2015.

The story had initially been passed down orally, and then written in English by a former colonel of the Hawaiian Kingdom, during a time the Hawaiian language was banned. Published in the Hawaiian Almanac in 1907, it included the role and description of māhū.

This forgotten document led to the Oscar-nominated animated short film, "Kapaemāhu," which was produced, directed, and written by Wong-Kalu alongside fellow filmmakers Joe Wilson and Dean Hamer. The film, broadcast on PBS, also was part of a large exhibit at the Bishop Museum of Honolulu last summer that remains accessible as a virtual tour.

“What some people call legends are actually elements of our history,” Wong-Kalu said in an interview with Ka Wai Ola. “The stones of Kapaemāhū are more than a tourist site. They are an insight into our Pacific understandings of male and female, life and healing, and the spiritual connections between us all.”

The exhibit not only amplifies the history of the stones, but features stories from māhū throughout history, and traditional healing treatments practiced by māhū and others today. Wong-Kalu says Hawaiian culture places a greater emphasis on the importance of what one can contribute to society—whether male, female, or māhū.

“It is a doorway into respect and shared aloha when we honor this understanding,” she says.

Combating discrimination

Many who currently identify as māhū are carrying out the roles of their revered ancestors, but it hasn’t been easy to do so. As māhū became marginalized, the meaning of the word became used as a slur aimed at most in the queer community, leaving many to eventually conflate māhū’s spiritual way of being with sexuality.

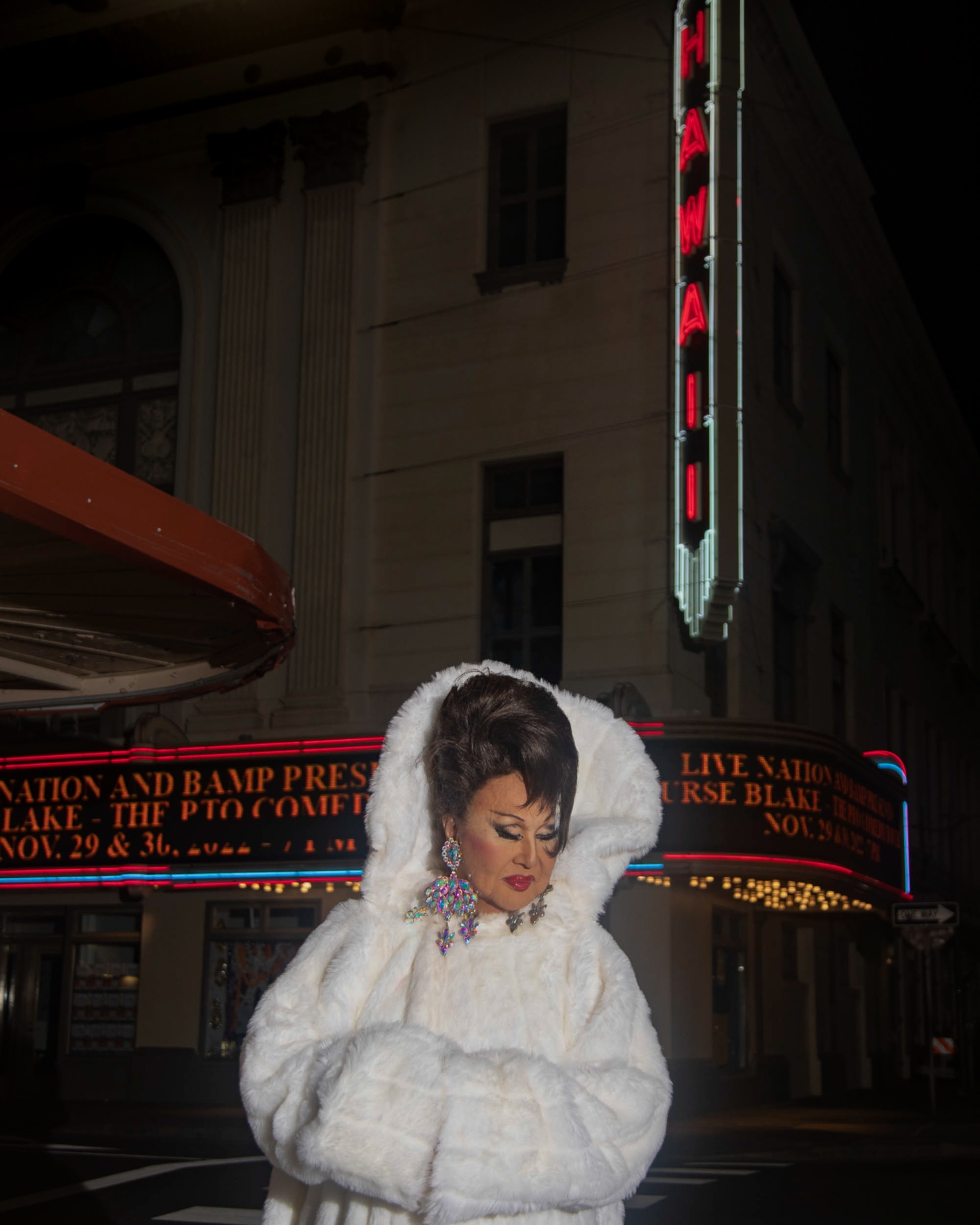

In the 1960s, when drag culture surged in Honolulu’s Chinatown district, some māhū and others in the queer community found kindred family at a former drag nightclub commonly known as The Glade.

But they were often victims of violence and discrimination, including legislation that once required many māhū and transgender women to wear buttons that said, “I AM A BOY.” For a decade, those caught not wearing the pins could be fined under an “intent to deceive” statutory clause, which was finally rescinded in 1972.

Māhū writer and historian Adam Keawe Manalo-Camp, whose mother was a seamstress for The Glade entertainers, says he didn’t know what māhū truly meant until the 1990s. Growing up in the Native Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement—a grassroots campaign to re-establish an independent Hawaiian nation—Manalo-Camp says he couldn’t find a place for māhū and nobody was talking about it. So he started doing his own research, which is when he first found the historical figure Kaomi.

Kaomi, whose story is included in the Bishop Museum exhibit, was māhū and excelled in the healing arts and hula. Kaomi was also the aikāne (same-sex) lover of King Kamehameha III, the third king of Hawaii who ruled from 1825 to 1854.

Aikāne relationships were also once an integral part of Hawaiian society. But, like māhū, it conflicted with missionary values. When Kaomi’s relationship with the king was found out, he was exiled and died later from injuries following an attempt on his life.

Discrimination against māhū and others in the queer community continues today, says Manalo-Camp. “When you’re a targeted group you have to keep ensuring that you have a safe space. Also being a part of the group means that you have to define what that space is with every generation,” he says.

Identity and education

Throughout Polynesia, advocates have been creating spaces for Indigenous gender duality across Pacific cultures. One step in this process has been the new acronym, MVPFAFF+, which encompasses those not only in Hawaiʻi but also in Tahiti, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, and other countries.

Native Hawaiian health advocates have also created educational materials for healthcare providers to enable more culturally conscious care for māhū. The materials–backed by data from the Hawai’i Department of Health–assert that acknowledging distinct histories helps combat further erasure–something that was echoed by the community and public officials during calls to update the signage over the four healer stones.

The new signage is slated to be installed in time for Honolulu Pride Month in October.

Kaumakaiwa Kanaka’ole, a prominent hula practitioner and international recording artist who composed the chant in the short film Kapaemāhū, says she first learned about the healer stones when she was in her Hawaiian immersion school as a youth. But she didn’t know it involved māhū until she became friends with Wong-Kalu much later.

“It’s not good enough anymore as a 21st century Native Hawaiian Queer that I, as a Native Hawaiian, was here, that I exist, that I matter,” she says. “It also matters to me that the part of me who is māhū also has a lineage equally as profound and equally as deep and meaningful.”