A new study of ancient tablets could reveal more about life in the Roman Army

50 years after the first Vindolanda tablet was discovered, scientists are looking at how these extraordinary artifacts were made.

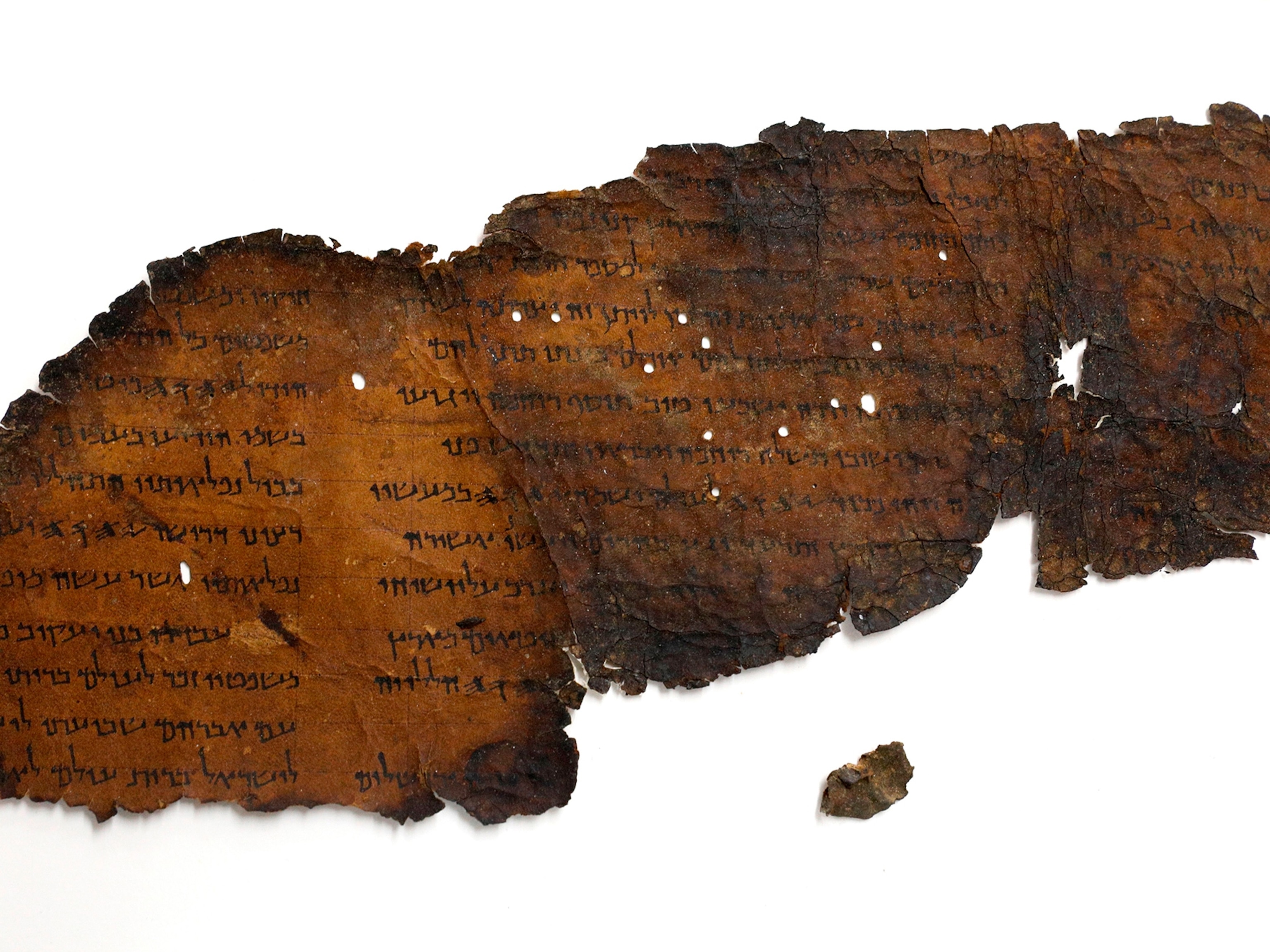

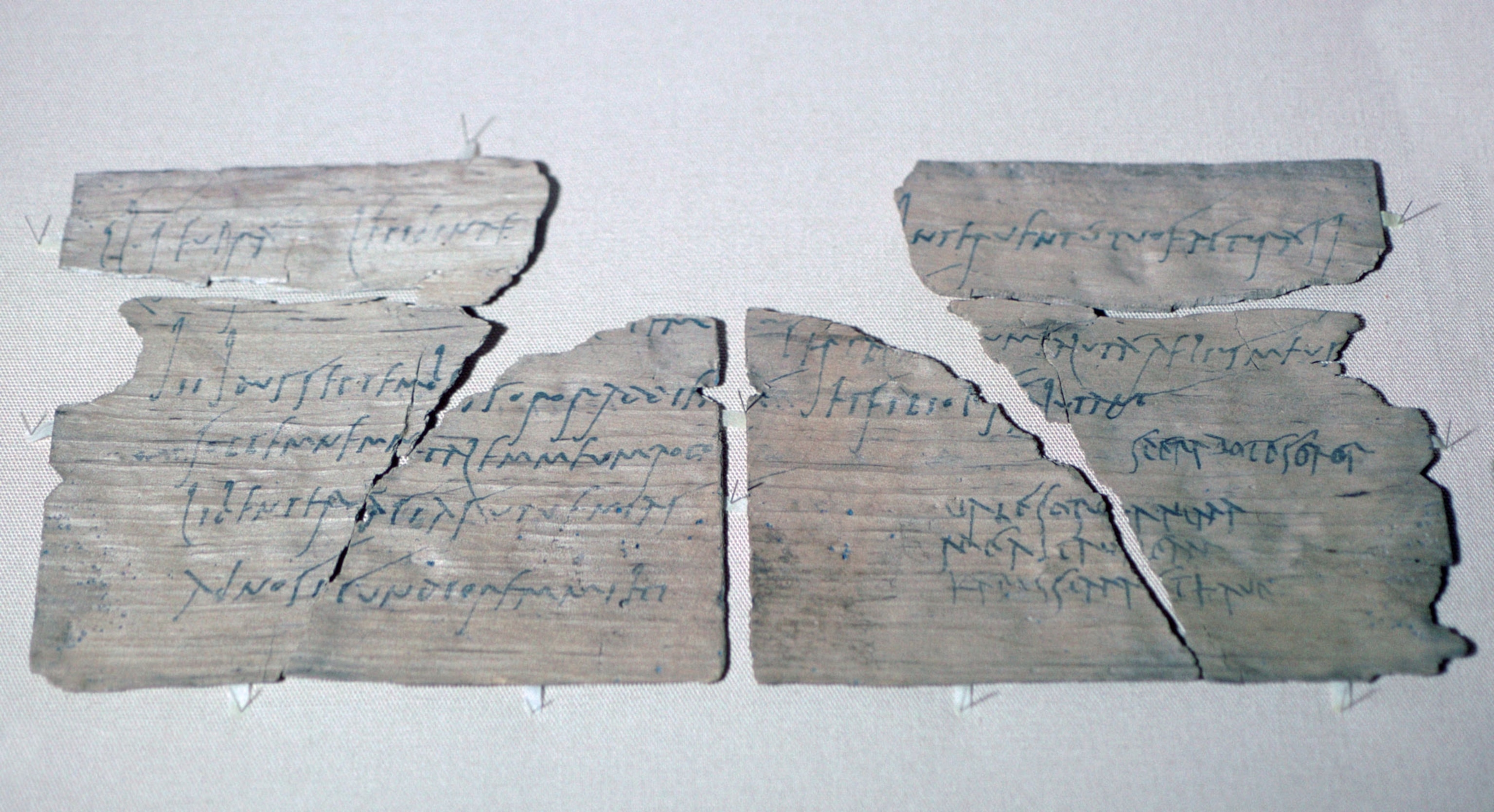

We’ll never know what was written on the first Vindolanda tablet found in modern times. The postcard-sized wafer of wood was discovered in 1973, during excavations of a 1900-year-old Roman fort in the north of England.

“It was found by accident, really, by my dad,” says archaeologist Andrew Birley, who now directs excavations at the Vindolanda fort. At the time, his father Robin Birley—also an archaeologist—was digging for Roman artifacts at the site, located just south of the ancient fortification known as Hadrian’s Wall.

“He was having a break, and he found two oily pieces of wood in the trench,” Birley recalls. “He picked them up and rubbed them between his fingers. And when he did that, the two pieces came apart—and he was confronted with the writing.”

That first writing tablet wasn’t preserved because archaeologists at the time didn’t realize how fragile the ancient wooden artifacts were. But since then, more than 1,800 similar tablets have been found among other buried artifacts at Vindolanda, and they’re now recognized as some of the world’s greatest archaeological treasures: the everyday writings of Roman soldiers and their families who lived at the fort, offering an unparalleled and intimate record of life on the Roman frontier.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the first Vindolanda tablet, the British Museum in London is conducting a new analysis of the materials used to make the Vindolanda tablets, in the hope that by studying the mediums of the tablets they can complement their messages.

Writing 'everywhere'

Birley is the third generation of his family to work at Vindolanda: his grandfather was the Oxford professor Eric Birley, one of the pioneers of studies of the fort and Hadrian’s Wall. “We’re like the Mafia,” he jokes.

While the remains of the Vindolanda fort (named from a Latinized Celtic word that means “white fields”) and an associated museum are now a popular tourist attraction, archaeological excavations are still carried out at the site and it is an important source of Roman artifacts.

Writing tablets are still being found at Vindolanda: Birley notes the first for the year was discovered in April, and he expects hundreds more from excavations over the summer.

“... I have sent you ... pairs of socks from Sattua, two pairs of sandals and two pairs of underpants (...). Greet (...) Elpis, (...), Tetricus and all your messmates with whom I pray that you live in the greatest good fortune."VT 346, A letter for gifts to a soldier stationed at the Vindolanda fort

Most of the tablets were written in ink on wood, but about 400 of them were written with a stylus on a layer of beeswax in a recess in the tablet. Only fragments of the wax now remain in the corners of these tablets, but in many cases the writing on the wax has left scratches on the wood beneath that can be read. The tablets are usually found deep underground, where the damp earth and lack of oxygen prevent the wooden items from decaying. (Unfortunately, the Vindolanda site is becoming unstable because of climate change, which causes it to alternately become drier and then wetter, says Birley, and that means yet-undiscovered writing tablets are less likely to survive in the coming years.)

Ordinary Roman soldiers were taught to read and write—uncommon skills at the time—and the Vindolanda tablets cover almost every aspect of life in a Roman frontier fort, including household matters, letters to friends, and official requests for leave. “Writing is everywhere, particularly in the military,” Birley says. “It was really important that people learned how to read and write, to communicate and to function.” That point is driven home by where archaeologists are discovering the tablets: not in a centralized, administrative area, but all around the fort and surrounding residences.

“[O]n the floors, inside people’s rooms—they’re all over the place,” says Birley.

"...chickens: twenty, a hundred apples, if you can find nice ones, a hundred or two hundred eggs, if they are for sale there at a fair price..."VT 302, An order for foodstuffs, probably by a slave for the commander’s residence

The most famous of the Vindolanda tablets was written in about A.D. 100 by a woman named Claudia Severa, the wife of a commander of a nearby fort. In it she addresses Sulpicia Lepidina, the wife of the commander of a cohort at Vindolanda, and invites her to a birthday party: “I shall expect you, sister,” reads the letter. “Farewell, sister my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail.” This is one of the earliest-known writings in Latin by a woman.

Scientific study

Five decades after the discovery of the first Vindolanda tablet, the British Museum is undertaking a new study to better understand how they were made. Museum scientist Caroline Cartwright, who specializes in the preservation of ancient artifacts, says that about 80 of the tablets have been studied so far.

Each examination looks closely at the wood the tablet is made from, the chemical composition of the ink (where it was used), and whether the tablets were prepared with another substance before being written on.

The scientists are also using electron microscopy to analyze the wood, multispectral imaging to reveal details of the writing under different light wavelengths, and Raman spectroscopy to determine chemical compositions—all methods that weren’t available to earlier researchers of the tablets, she says.

"...the Britons are unprotected by armor. There are very many cavalry. The cavalry do not use swords nor do the wretched Britons mount in order to throw javelins."VT 164, Part of a military memorandum about the fighting qualities of the native Britons

While the ink tablets seem to be everyday letters, the wax tablets tend to be more official: “They might be someone’s will, or an agreement about who owns a slave,” says Richard Hobbs, the curator at the British Museum responsible for the Vindolanda tablets. “We are at the very early stage of reading these.”

Most of the ink tablets seem to be written on thin sheets made from local woods like birch or alder. The wood in the wax tablets tends be softer says Cartwright, and may have been recycled from barrels that held imports from other parts of the Roman Empire.

Far from home

Along with the intimate insights into everyday life in the ancient world, the Vindolanda tablets are also prized for the important information they provide about Roman military operations on a remote edge of the empire.

“The Roman Army was an extremely complex organization, but we know little about how it was administered, and most of the previous records came from the east of the empire,” says Hobbs. “But these tablets give us an amazing insight into life in the Roman Army on the northwest frontier.”

About half of the 300,000 Roman Army soldiers stationed in Britain were citizen legionaries. The rest were auxiliary troops (auxilia) who had signed up to fight for the Romans for 25 years, with the promise of being granted citizenship at the end of their enlistment. Many auxilia were native to Britain, but other auxiliary troops came from more distant territories, sent far from their homes by Roman authorities who were suspicious of their loyalties: one unit at Vindolanda, for example, were skilled horse troops from what is now the Netherlands; others were from Belgium and northern Spain.

Regardless of where the troops originated, however, the Vindolanda tablets shows most read and wrote in Latin, the language of the army. Birley explains that some of the Vindolanda tablets even have Latin writing lessons on them.

“You’re dealing with lots of people who come from different backgrounds, and they have to be able to communicate with each other,” he says. Almost everything was written down, including how much the soldiers were paid and their requests for stores and supplies: “If you want to join the Roman Army, it’s really important that you achieve a certain amount of literacy.”

Birley adds that the scientific work being done by the British Museum on the materials of the Vindolanda tablets will help to preserve them for as long as possible.

“It’s really important and innovate work," he says appreciatively, "and it helps us with the long-term storage, curation, and management of these incredibly precious things.”