Can you get bird flu from eggs? Here are the answers to all your pressing questions.

We talked to experts about where the science is on risks to humans and how the virus is messing with the food supply.

Bird flu continues to make headlines in the United States, and the longer it lingers, the greater danger it poses to humans.

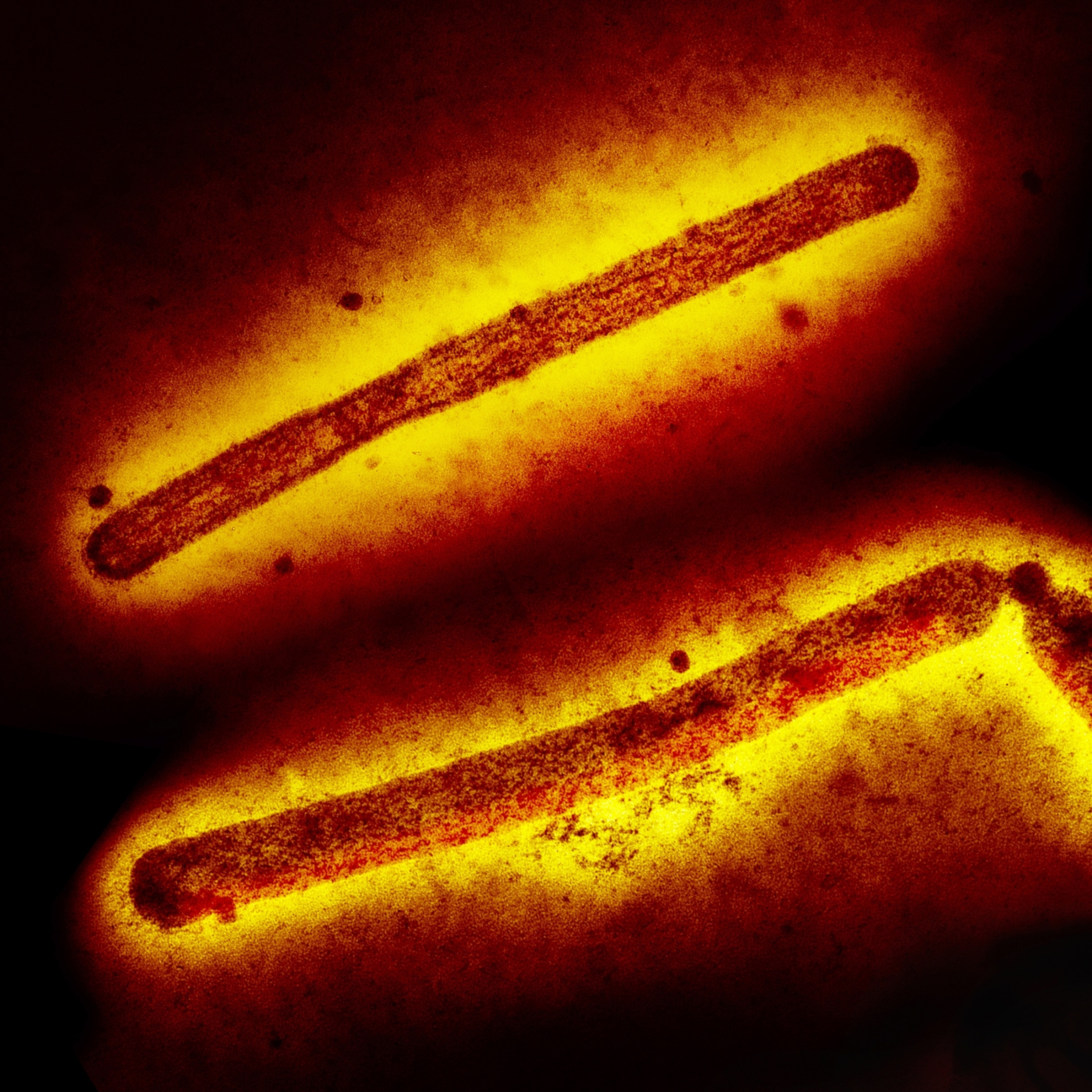

H5N1, the strain of avian influenza A that’s currently circulating in the U.S., primarily harms birds but has infected over 200 mammals since 2022, including dozens of house cats and hundreds of cattle herds. The virus has also contributed to the deaths of tens of millions of chickens—causing egg shortages, skyrocketing prices, and closing poultry markets in at least one state.

Reports of another bird flu virus called H5N9 on a duck farm in California, a new H5N1 variant spreading in cattle, and a cat possibly infecting its owner all add to concerns that a more dangerous and infectious version of the virus might yet evolve.

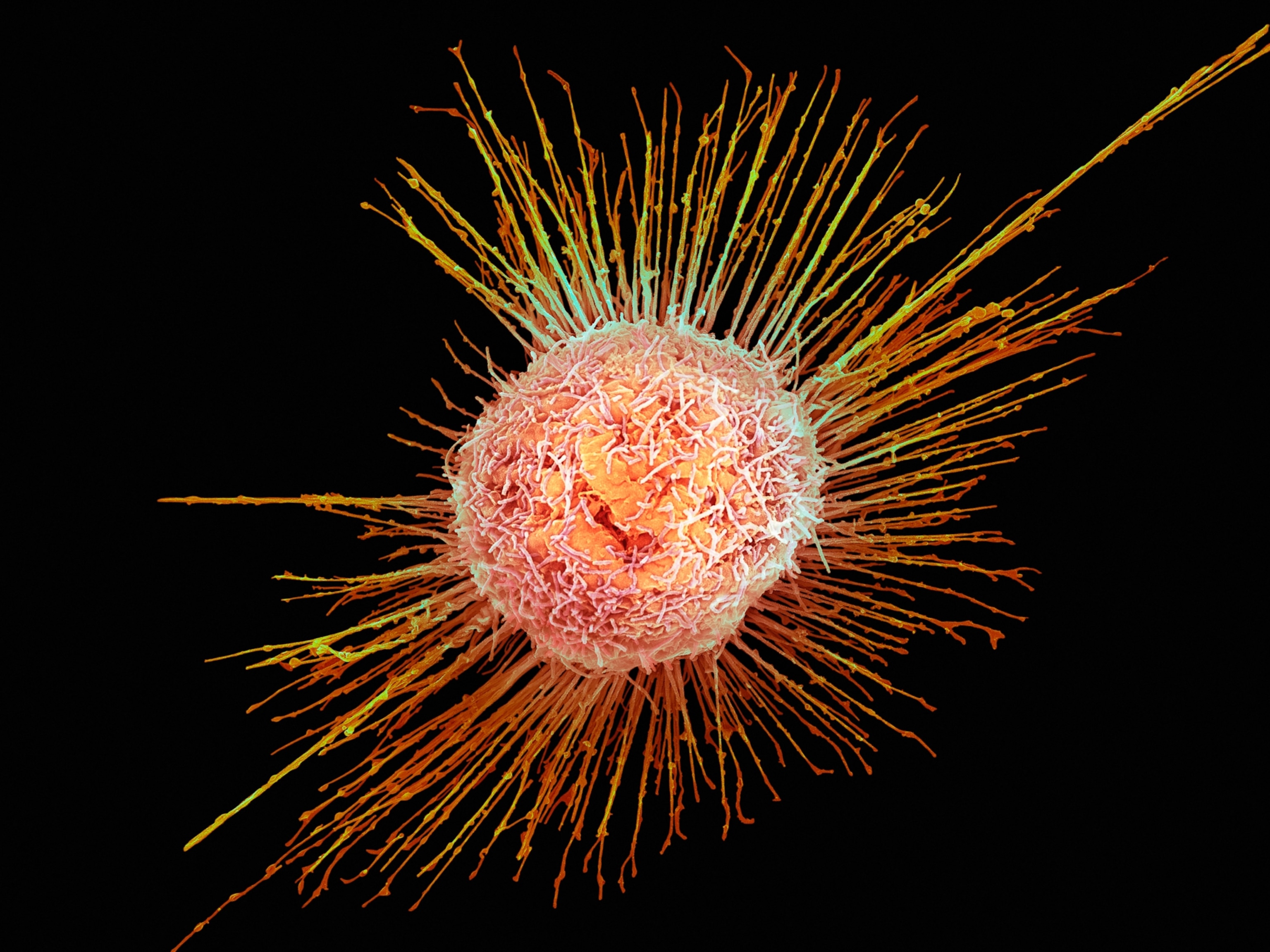

As the number of human cases rise as well, some fear we could even end up with another pandemic on our hands.

"The more this circulates and the more human cases that occur, the greater the risk that a virus will emerge that is capable of transmitting efficiently from human to human," says Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. "That is what we really need to avoid in order to prevent another pandemic from happening."

Here's how serious bird flu actually is, why it's disrupting the food supply, and what can be done to protect your pets and loved ones.

How serious is bird flu in humans?

The version of the virus that began infecting people in the U.S. last year appears to be significantly less lethal than the version behind past human cases. For the 900 plus human H5N1 cases (most of them across Asia) that were recorded from 2003 to 2023, for instance, more than half proved to be fatal. In the current U.S. outbreak, only one of the 68 confirmed cases ended in death.

"For the most part, human cases in the United States have been mild," says Peter Halfmann, a virologist at the Influenza Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Cases may be milder for a few possible reasons: The virus may have become less virulent over the years, immunity to annual influenza strains may have provided us with some level of protection, and most of the cases of the disease so far in humans have occurred through interactions with infected cattle—and the virus isn't as serious or as deadly in that species.

The form of the H5N1 virus infecting cattle is a variant called B3.13, while a variant called D1.1 is behind the outbreaks in wild birds and on poultry farms and the one human death in the country. (This more dangerous variant in birds might also explain why infected house cats are becoming especially ill, since they are more likely to interact with and attack infected birds that fly into the yard.)

More serious variants could yet pose greater risk to humans, however, as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) just announced that D1.1 has been detected in Nevada cows. One dairy worker has already tested positive for the variant, as well, and more severe cases could result if it spreads widely in cattle.

For now, though, one promising fact remains true: "There is still no evidence of human-to-human transmission," says Rasmussen.

Can you get bird flu from eggs, meat, or other foods?

Also encouraging is that none of the U.S. human cases have been definitively linked to food, so the risk of contaminated food making it to the kitchen table remains low. One reason for this is that the USDA tests all beef that enters the market to ensure that it is not contaminated. In December, the agency began bulk testing milk as well.

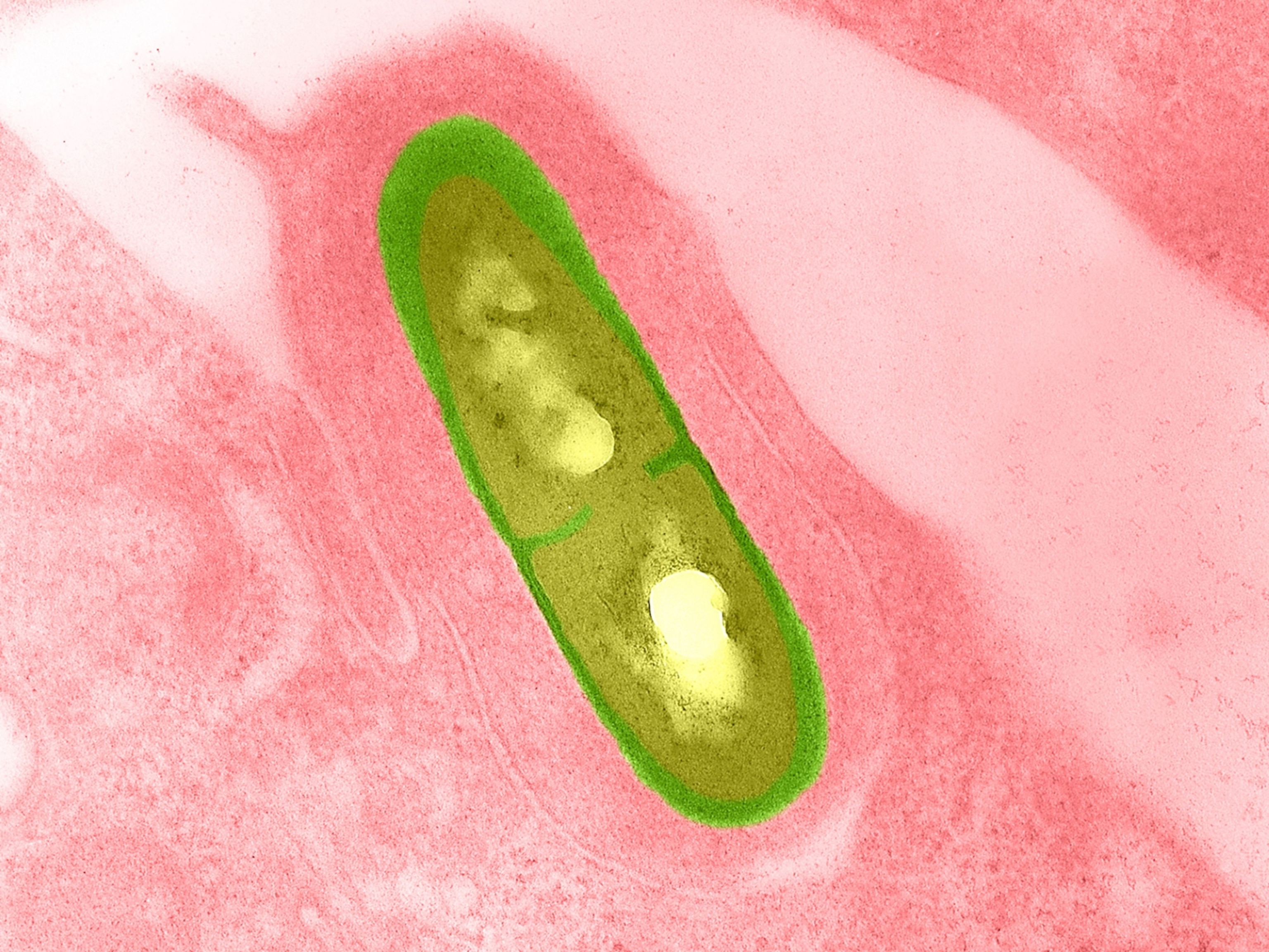

Cooking meat to recommended temperatures will also kill H5N1 and render it safe for consumption. Pasteurization does the same for milk and eggs. "I have no concerns about the safety of properly pasteurized milk or cooked meat and eggs as this virus is not very hardy and pasteurization and cooking should kill it easily," says Scott Weese, a pathobiologist and veterinarian at the University of Guelph in Canada.

This is why, even though USDA tests have discovered trace amounts of the virus in as much as 25 to 30 percent of America’s milk supply, multiple U.S. Food and Drug Administration safety tests have shown that the virus isn't viable in pasteurized milk and therefore won't cause harm, says Seema Lakdawala, a molecular virologist at Emory University in Atlanta.

The same can't be said for unpasteurized milk, however. "There were reports of a H5N1 infection in a child in California being associated with consuming raw milk, though that was not diagnostically confirmed," says Benjamin Anderson, an epidemiologist who is leading the Emerging Pathogens Institute bird flu response team at the University of Florida. Even still, he adds, "given what we know about how raw milk can contain very high concentrations of virus, it is likely that drinking contaminated milk would result in possible human infection."

Raw or unpasteurized pet food poses similar risks. This is why several unpasteurized milk products advertised for pet use have been recalled due to bird flu contamination—and the death of a house cat in Oregon was linked to contaminated raw pet food.

How is the virus impacting America’s food supply?

While food products don’t pose an infection risk if processed and cooked properly, the virus is still having a huge impact on farms and grocery stores because of the sheer volume of livestock impacted: over 900 cattle herds infected, close to 150 million farm and aquatic birds contaminated, and more than 20 million egg-laying chickens killed—plus another 13.2 million chickens culled in an effort to contain the disease.

Moreover, after infected flocks have been culled, the farmer or manufacturer "needs to then focus on cleaning up and undergoing a USDA biosecurity inspection before they can start re-stocking—a separate process that can take several months longer," explains Meghan Davis, a veterinarian at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

All of this, and the fact that even if an infected chicken doesn't die, "it will not lay eggs," is why egg shortages are rampant and why prices keep climbing, Lakdawala notes.

The U.S. cattle infestation further disrupts milk production and distribution since "most infected dairy cows don't produce milk and even temporarily lose the ability to regain milk production after recovering from the illness," says Halfmann.

Reinfection may also occur, further extending delays—especially when more mild symptoms go unnoticed. "Cows will be protected from some of the worst outcomes of the disease after their initial infection, but not necessarily protected from getting infected again—especially if the timing between the first and second exposure is long," says Richard Webby, a virologist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and the director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds.

(Bird flu is spreading from pole to pole. Here’s why it matters.)

Staying safe based on where things stand today

While the risk of bird flu currently remains low for most people, there are several commonsense measures you can take to help prevent the virus from infecting your pet or loved ones.

One such measure is buying only pasteurized animal products and cooking meat thoroughly. (And if you must drink unpasteurized milk, Anderson recommends boiling it first to reduce infection risk.)

It's also important for both humans and pets to stay away from dead, sick, or strangely acting animals in the wild "especially birds and cats," says Lakdawala, because the virus can be transmitted through secretions of infected animals.

Davis says it’s also wise to wear protective equipment such as face shields, masks, coveralls, and gloves if you’re one who works closely with dairy cows, poultry, wild birds, or sick animals in farm, zoo, or veterinary settings.

Staying up to date on your flu vaccine "could also help reduce the severity of a bird flu infection if an individual becomes infected," adds Halfmann.

Protecting against seasonal flu also reduces broader risks that could harm more people. “We want to limit transmission of human flu since a very concerning situation would be someone having both bird flu and seasonal flu, which could create the chance for a new flu virus to occur that has the ability to transmit between people," says Weese.

This is one reason the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued an advisory to increase bird flu testing among people who present at the hospital with flu-like symptoms. Doing so could also help identify subtypes of the virus and reveal where infections are occurring to make sure human-to-human transmission doesn’t start happening without our knowledge.

"We are still in a situation where the circulating virus is poorly infectious for humans,” says Webby, “but a single mutation could change that quickly and people should be educated and aware.”