Mobile, Alabama — It was one of the greatest unsolved crimes of the 19th century. Now a team of archaeologists is hunting for the smoking gun—the charred wreck of the Clotilda, the last slave ship to reach the United States before the outbreak of the Civil War.

Experts from the National Geographic Society have joined marine archaeologists and divers from Search, Inc., and the Slave Wrecks Project of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture in an intensive survey of a muddy branch of the Mobile River where the vessel is thought to lie.

The Alabama Historical Commission (AHC) sponsored the expedition after a local reporter found what was thought to be the wreck earlier this year, focusing national attention on the vessel. Though it turned out to be another ship, it brought to the surface an important, if painful, era in the state's and nation's past.

“Many tourists like to come visit our plantation houses, but this is the true symbol of the horrors of slavery,” said Lisa Jones, executive director of AHC.

The Clotilda, however, was no ordinary slaver, for the roots of its voyage extend to both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. The mastermind was Captain Timothy Meaher, a wealthy Mobile shipbuilder, riverboat captain, and plantation owner, who was born in Ireland and raised in Maine. Meaher allegedly wagered several Northern businessmen $1,000 that he could smuggle a cargo of Africans into Mobile Bay under the nose of federal officials—and act of piracy punishable by death that had been banned in the U.S. since 1805.

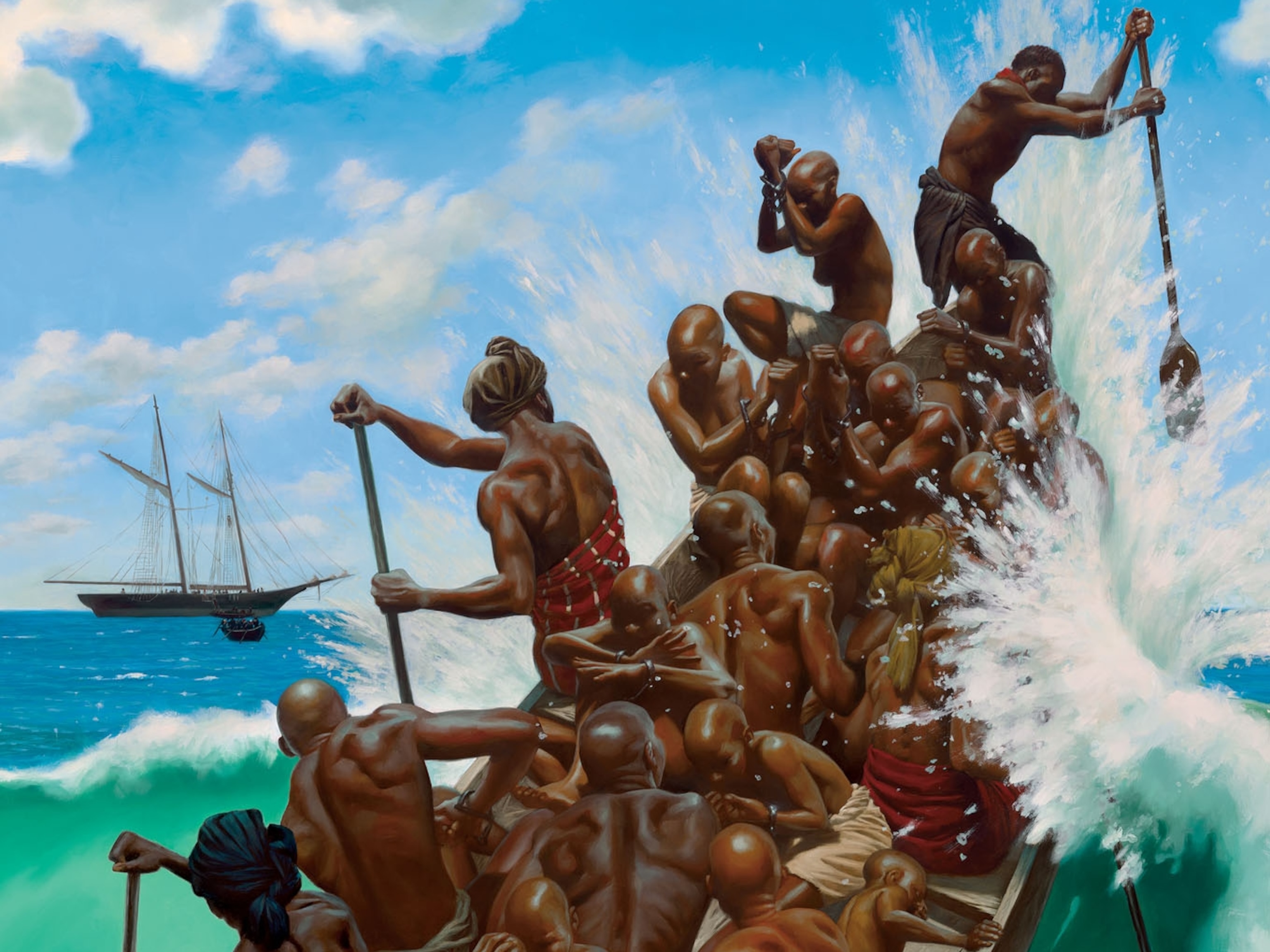

Undeterred, Meaher hired Captain William Foster, a native of Nova Scotia, to take his fast, new schooner to the infamous slave port of Whydah in present-day Benin to purchase a cargo of captives for $9,000 in gold. He returned in July 1860 with 110 humans on board, snuck them up the braided Mobile River under cover of night, and offloaded them onto a riverboat.

The captives were taken farther upstream and hidden deep in the swamps until they could be transferred to plantations owned by Meaher, his two brothers, and their associates. Foster then burned his ship to the waterline to hide the evidence of his crime.

The widely reported story made Meaher and Foster heroes throughout the South. They were indicted by the local U.S. attorney but never convicted. The charges became moot six months later after Alabama seceded from the Union.

It was the Clotilda's passengers, however, who made the ship unique. After the Civil War, the West African captives who had remained on local plantations reunited and settled on a wild bank of the river known as Plateau, just north of Mobile. There they elected a chief, built simple homes, and resurrected many of their African customs. Though they eventually intermarried with other freed slaves, the tightly knit, fiercely independent community became known as Africatown.

Descendants of those original Africans brought over on the Clotilda still live in Africatown today, providing an unbroken genealogical record for their families unavailable to most African-Americans. Despite their obvious presence, their story was repeatedly denied by Meaher, Foster, and others in Mobile, blurring the lines between fact and fiction.

“The stories about Clotilda were always taught in our home,” said Lorna Woods, a local historian and descendant of Charlie Lewis, one of the West Africans who settled in the community. “People just didn't talk to folks in this neighborhood. Mr. Meaher was a powerful man and he didn't want the story to get out. But this is a major part of our history, as important as the Amistad or the Titanic.”

The team of archaeologists—led by James Delgado, former head of maritime archaeology for the National Park Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—is using high-resolution sonar and other sensing devices to search a muddy, two-mile stretch of the Mobile River for remains of the burned vessel.

“I get goosebumps when I think we may provide conclusive evidence for this missing piece of American history,” said National Geographic archaeologist Fred Heibert. “One of the most important things that archaeology can provide is closure to stories that have no conclusion.”