Neil deGrasse Tyson hardly needs an introduction. The host of National Geographic Channel’s StarTalk, director of the Hayden Planetarium and ubiquitous media star, he has helped bring the mysteries of space science into our living rooms. In his new book, Accessory to War: The Unspoken Alliance Between Astrophysics and the Military, Tyson and writer-researcher Avis Lang chart the long but often hidden collaboration between “sky watchers” and the military, from the invention of the telescope to GPS.

Speaking from his publisher’s office in New York, Tyson explained how the first use of Galileo’s telescope was military, how GPS determined the outcome of the Second Gulf War, and why, despite his anti-war views, he regards the collaboration between the military and science as a two-way street.

You write, “The universe is both the ultimate frontier and the highest of high grounds. Shared by both space scientists and space warriors, it’s a laboratory for one and a battlefield for the other.” Unpack that idea for us, with some examples.

This shared technology of methods and tools has been going on since the beginning of nations. If you wanted to know what was on the other side of the ocean, or if you wanted to dominate it, you needed to navigate your way there. And the only way you could do that was with an understanding of the sun, moon, and stars. Who could provide that? The astronomer.

Galileo, who perfected the telescope in 1609, wanted to look at the sky, but that was not the first thing he did with it. He showed it to the Doge of Venice, and they went up into the high clock tower and looked down onto the lagoon. He told the Doge, “You can identify whether the ship is friend or foe ten times farther away than you can with an unaided eye.” So, the telescope’s value to reconnaissance and intelligence-gathering was immediate! And it’s been used in similar ways ever since.

In June, President Trump directed the Pentagon to create “a space force” as the sixth military branch. What implications does this have for the future? Is there an international effort to prevent space from becoming the battlefield of the future?

Great question! I’ll take them in reverse order. In 1967, the United Nations prepared a treaty for the peaceful use of space. It’s very hopeful, just as the UN was back in the 1960s. But it left open the need to defend your assets in space. For example, I have a laser and you’ve got a satellite that’s irritating me; can I take you out? Does that count as defense? There’s some grey area in there but the spirit of that treaty is noble and something to hold to our hearts.

Now, to create a space force is to do two things. It’s to shift all space activities out from under the umbrella of the Air Force. By the way, we’ve been using space assets in the service of our military interests since the 1960s! This is not some new initiative. The difference is, when we talk about a “Space Force” we tend to think of weapons rather than reconnaissance, and weapons are not realistic things to put in space. What are you going to do, destroy a satellite? No. If you destroy a satellite, you’ve busted it into hundreds of pieces, which are now moving at 18,000 miles an hour and become projectiles that can damage your own satellites. So, the concept of weapons destroying things in space, certainly in Earth’s orbit, is simply not realistic. The platform is much better served as a place of reconnaissance rather than a place of battle.

Today, we all take GPS for granted. But 30 years ago it led to a revolution in warfare. Talk us through what Arthur C. Clarke called “the world’s first satellite war.”

GPS was conceived, positioned, and launched by the U.S. Air Force in their Space Command division. Like navigation in antiquity, you want to know where you are, where your targets are, where you’re headed, and how to get back home. We no longer need the astronomer sitting next to the captain of the ship. We have space-borne assets that calculate our coordinates in four dimensions: longitude, latitude, elevation, and the precise time. So, if you are coordinating an assault, GPS is giving you information so you can make that happen in a coordinated way.

Those satellites were a fundamental contributor to the success and efficiency of the Second Gulf War in 2003. And it’s not clear how we would be fighting any war of the future without space assets. That leaves a certain vulnerability, right? If someone takes out our GPS satellites, we’re blind. And no one remembers how to use a sextant. [laughs] So, protecting those assets becomes a very high priority.

We’ve all marveled at the Hubble Space Telescope’s photographs of outer space. But I was surprised to discover that it, too, has a military dimension. Tell us about “KEYHOLE” in the 1970s and how images from space are crucial to warfare.

The KEYHOLE project consisted of versions of the Hubble telescope that preceded it in orbit around the Earth. It was basically reconnaissance telescopes. Once some of the technology was declassified, we recognized that we could instantly exploit the engineering innovations and testing that had already taken place in the military. Thus, the Hubble telescope did not have to be conceived from scratch.

Here’s another example. The military developed a method to stabilize the wiggling appearance of starlight passing through the atmosphere, because it is turbulent and prevents you from seeing a stable image of what’s out there. Why did they care? Because, if there was something moving in the atmosphere, they wanted to track it precisely and take it out by aiming exactly where the thing was, not where some phantom image of it led them to think it is.

So, the military invented a system known as Adaptive Optics. Oh my gosh, we astrophysicists wanted one of those, too! We didn’t even know they had one! When it was declassified, we immediately adopted Adaptive Optics methods and tools for our own observations, retrofitted our telescopes and built them into new telescopes. Now, when we observe the night sky, we have perfect imagery of starlight as it comes through the atmosphere.

Another example of science and war being joined at the hip is infrared astronomy. Tell us about the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

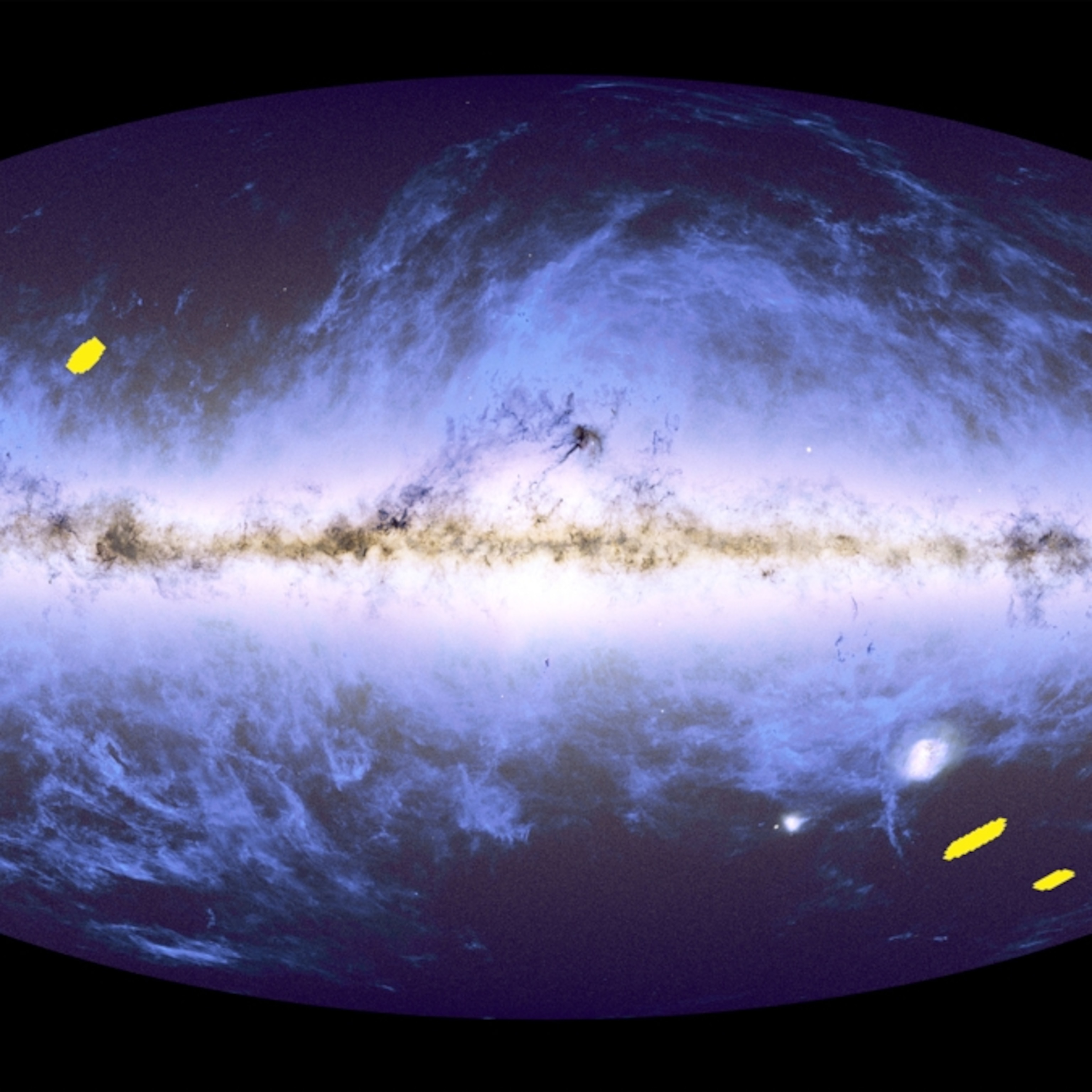

The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation is a big funder of educational TV. They also have a funding arm that cares about science literacy and education. Princeton, the University of Chicago, and other collaborators came together in the early nineties to propose a database of stars in the sky, as well as galaxies and quasars, which would be the greatest database ever collected for stellar objects. Ever!

The telescope was especially designed and tuned for this purpose with a high beta-rate, so that it could obtain data very quickly. But then we had to make a data pipeline. As the data comes in, you have to process, store, and analyze it. This pipeline required some ingenious programming and when the algorithms were published, they got noticed by the military. The head of the Sloan Project was invited to brief intelligence officers of the military on what new algorithms had been invented in order to handle that much data, because the military judged that they might have that need as well.

That’s a very recent example of the military using what we are doing. It’s a two-way street. We’re walking in opposite directions with a picket fence between us. We look over the fence and say, “I could use two of these and one of those” and they look over and say, “I’ll take five of those and six of the other.” That’s the two-way street.

The U.S. has long been the leading power in space. But there’s a new kid on the block, isn’t there? How much of a threat is China?

I have mixed feelings about this because we had the chance to invite China to be part of the International Space Station. But we said, “No, China, you’re not going to join because of human rights violations.” Rather than removing China, though, it just re-doubled China’s effort to become a space-faring nation. And that’s exactly what they did. They have launch bases and satellites; they launched the Shenzhou-5 spacecraft, becoming the third nation after Russia and the U.S. to launch a human being into space in their own rocket. They did an exercise where, from an Earth-based launch, they sent a missile that destroyed one of their satellites. It would be an act of war if they destroyed one of ours! So they destroyed one of their own. That’s not an act of war but it’s certainly a display of power, of capability.

There are people who are worried about China. I’m not as worried. We are so co-mingled with our economies and trade that I just don’t see them becoming a military adversary. At all. There could be some tensions here and there as there always are, but I’m not an expert.

Let’s get personal, Neil. You write, “Like the vast majority of astrophysicists, I am profoundly against war.” So how do you and your colleagues justify your contribution to the military?

In my old age, I’ve come to realize that my anti-war posture was completely shaped during the Vietnam War in an era that it is unthinkable that any war could be a good war. The difference is, unlike the physicist, whom you pay to make your bomb, or the biologist, whom you pay to weaponize anthrax, the astrophysicist is not paid to do any of these things. We do what we do, then the military reaches over because they’ve found something convenient.

How do we feel about that? We’re curiously complicit, like “OK, we can’t really control it because this is published work and it’s open in peer-reviewed journals, and so you can just take it.” What’s a little more complicit is when something is developed for the military and then we take it from them! If you had some deep, anti-war conscience you would not take it from them at all. But we do.

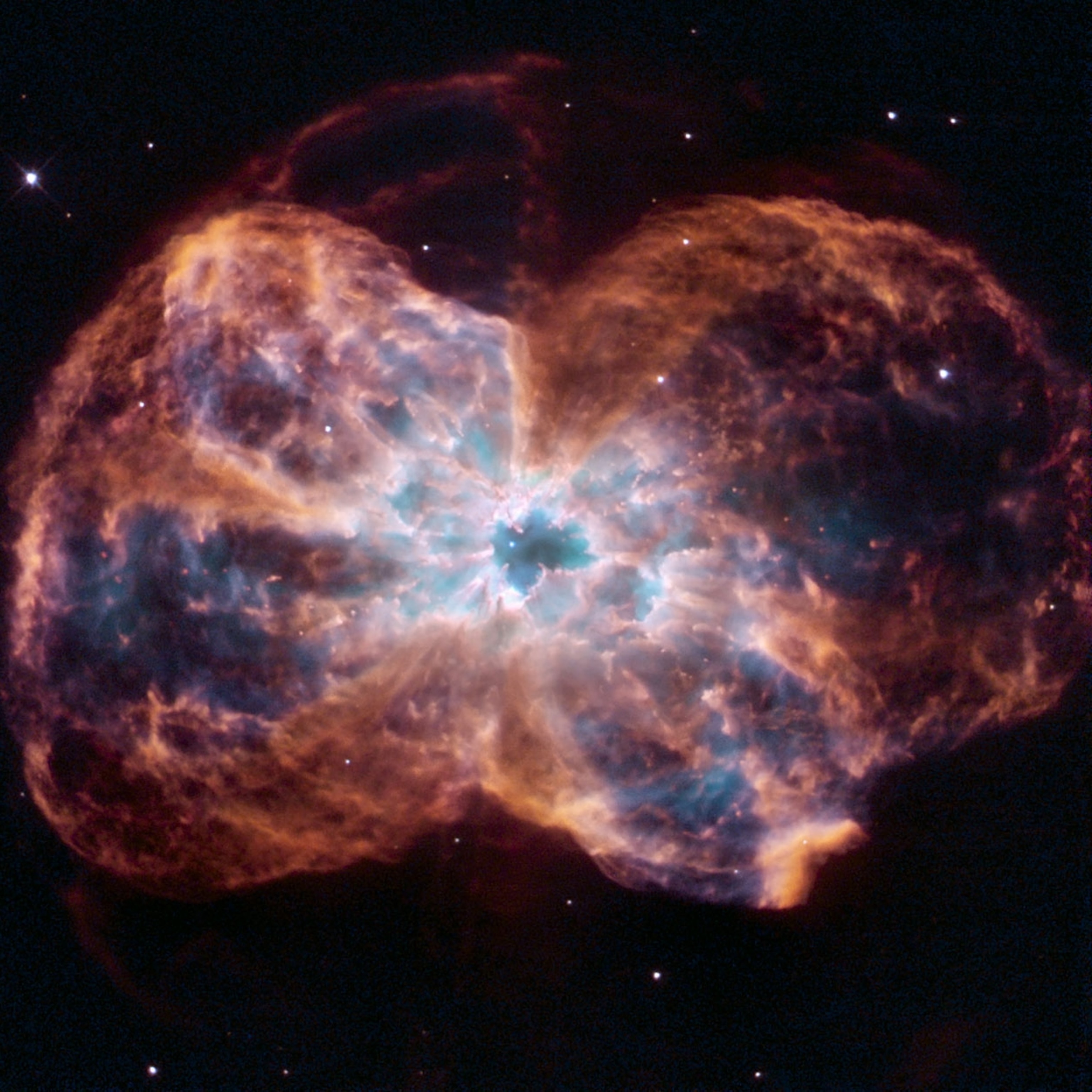

Luckily, the prime job of an astrophysicist remains to plumb the mysteries of space. Tell us about some of the wonderful discoveries being made today.

Yes! We have a sense of what’s to be discovered in the near and middle future because of the new telescopes and space probes that are being conceived. We want to go explore the ice moons of Jupiter where, beneath the icy outer layers, there are oceans that have been liquid for billions of years. I want to go ice fishing on those worlds to see if there’s life that swims up to the camera lens and licks it!

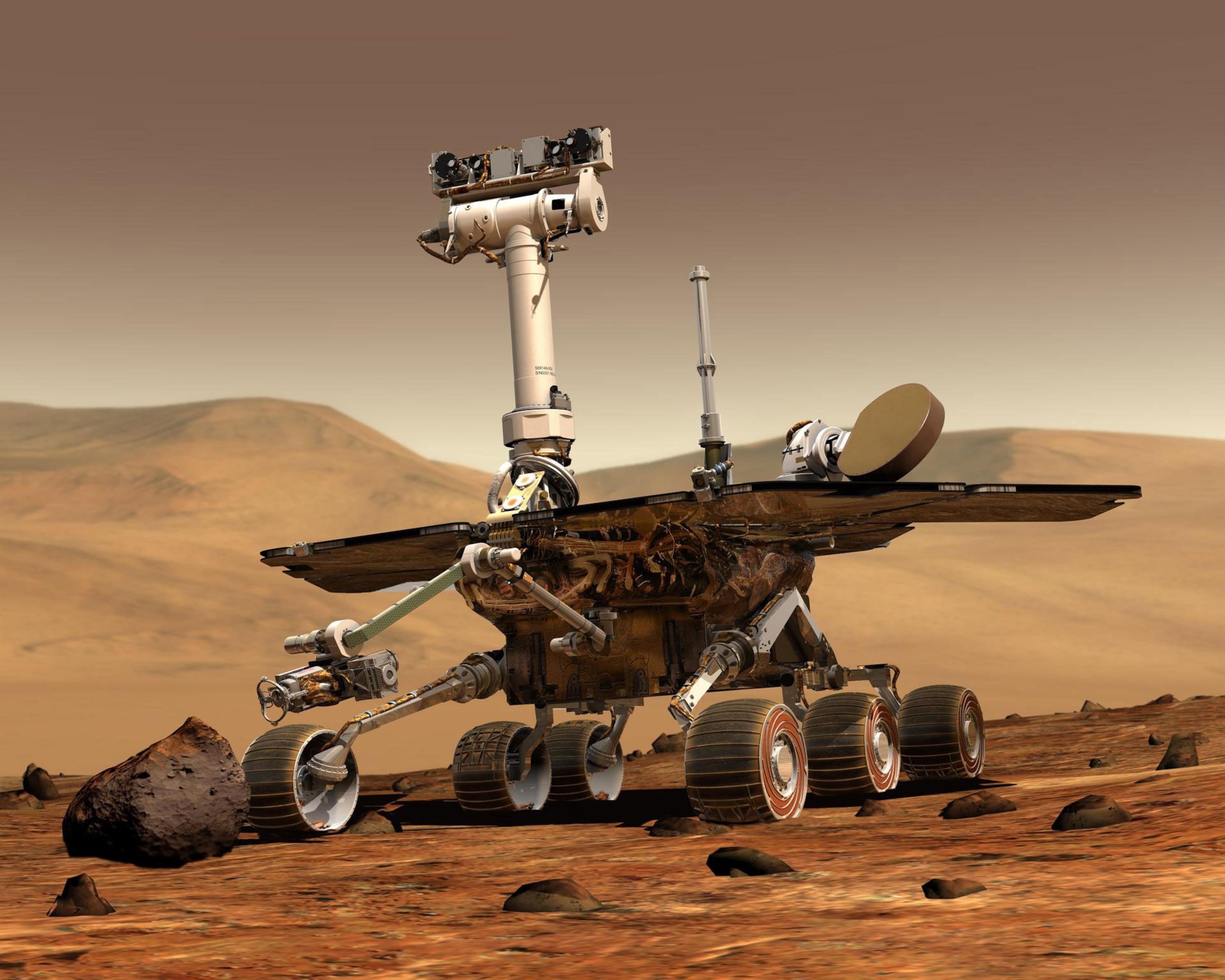

There are planetary probes landing on planetary surfaces, like the rovers on Mars. We will soon have the James Webb Space Telescope. We have specialized telescopes that are trying to solve the mysterious dark matter problem. We don’t know the origin of 85 percent of all the gravity in the universe; we call it the dark matter problem. It’s the longest unsolved problem in astrophysics, and it has been with us since 1936.

But to bring war back into this, we’ve visited asteroids and comets, and gotten close-up views of what they’re made of. So think about this: space basically has unlimited resources—energy, minerals, rare-Earth metals—and if you look at the cause of maybe a third or a half of all wars, they were fought over limited access to resources. If space has unlimited resources, there is a chance that the continued exploration of space will be the greatest force in the generation of peace the world has ever seen. That’s the hope I carry with me into the future.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.