Measles vaccines protect against more than just measles. Here's how.

Without vaccination, the highly contagious virus can allow other diseases to flourish in unsuspecting populations for more than two years after an infection.

Measles is alarmingly contagious: It’s spread through the air and can linger in a room for up to two hours after an infected person has left. The disease is responsible for more than a hundred thousand deaths each year among unvaccinated people.

What’s more, danger still lurks even for those who survive an outbreak.

Measles not only weakens your immune system in the short term, bouts with the virus seem to wipe your immune system's memory, causing the body to forget how to fight off things that you may have already conquered. For some people, this so-called immune amnesia may linger for months to years after an infection.

Now, a pair of studies published in Science and Science Immunology digs into the specific mechanism behind this detrimental side effect, comparing blood samples from unvaccinated children in the Netherlands before and after measles exposure.

These studies add even more weight to the importance of getting vaccinated, Colin Russell of the University of Amsterdam and senior author of the study in Science Immunology, says in a press release. Before the vaccine was introduced in 1963, it was nearly guaranteed that every child would catch measles, and an estimated 2.6 million died from the disease each year. The measles vaccine, which is often combined with mumps and rubella, is incredibly effective, with two doses imparting nearly 97-percent protection, resulting in dramatic declines in measles deaths around the world.

In recent years, though, measles has been once more on the rise. In 2018, 98 countries reported more cases than in the prior year, according to a UNICEF report released in March. While infrastructure issues and civil strife have been interfering with vaccination campaigns in some parts of the world, experts say there’s another issue behind the recent slew of cases: complacency about vaccination.

“The benefit of the vaccines has actually been kind of its own downfall,” says Yvonne Maldonado, an epidemiologist at Stanford Medical School. “People just don’t see this as a relevant intervention.”

However, the data show that’s not true: Not only did measles cases plummet once vaccine use became widespread, but cases of other diseases dropped as well—pneumococcus, diarrhea, and more. In resource-poor regions, the decline was as dramatic as 50 percent; in impoverished regions, it dropped by as much as 90 percent.

“We actually saw the whole overall baseline for childhood mortality drop precipitously,” says Harvard's Michael Mina, an author on a 2015 study analyzing this decline and lead author of the new study in Science. In essence, the measles vaccine seems to not only protect populations against measles, it may be keeping a slew of other infections at bay, and one way it could be doing this is through prevention of immune amnesia.

Anatomy of the infection

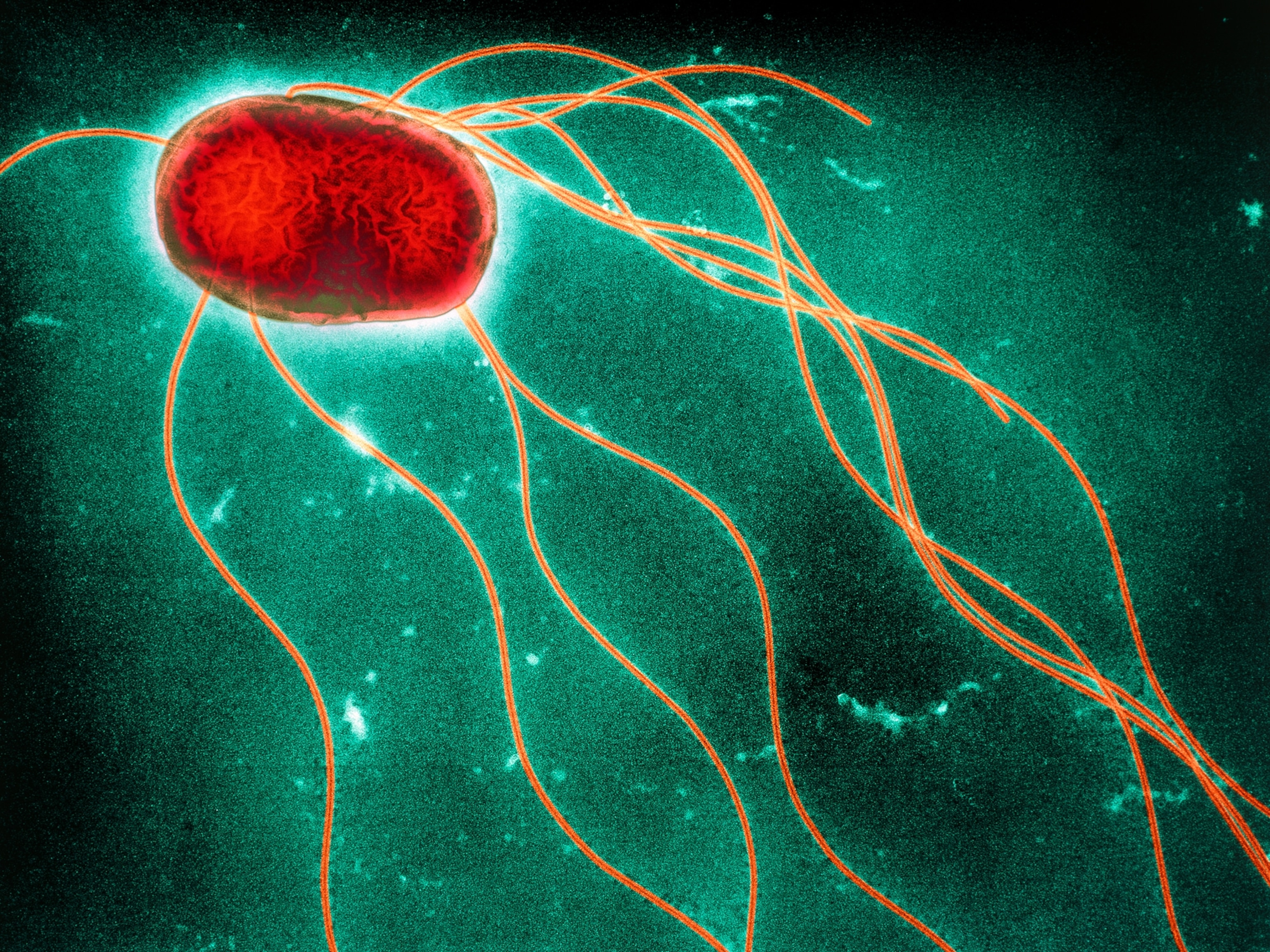

Over the years, scientists had accumulated clues to measles' mysterious mechanism, including the viruses' seeming proclivity for attacking the immune cells. But the puzzle remained incomplete. A 2012 study published in PLOS Pathogens, filled in one of those missing pieces.

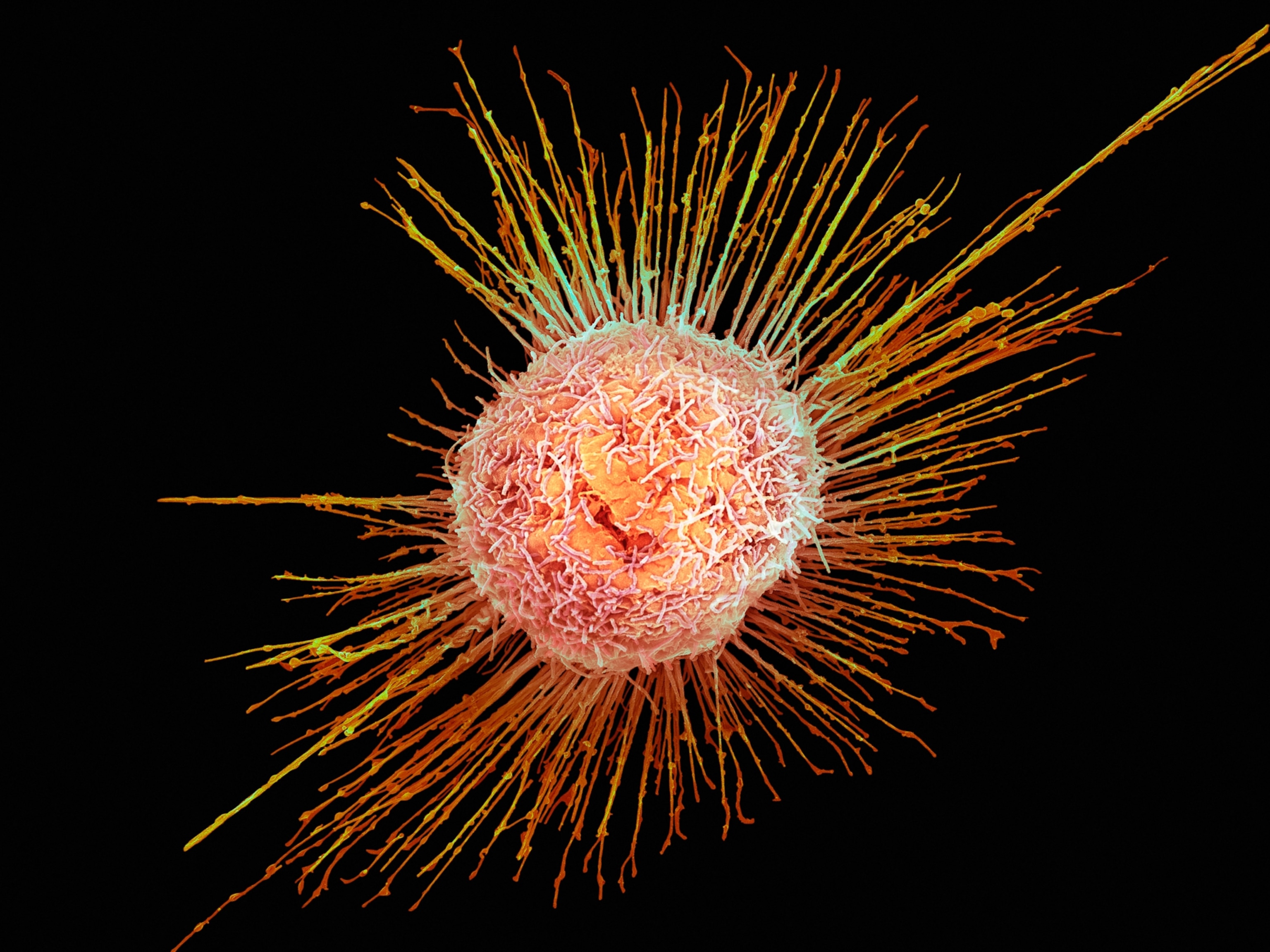

The team, led in part by Rik de Swart, an Erasmus University Medical Center virologist who coauthored both of the latest studies, exploited one viral necessity: To multiply and spread, a virus has to invade a cell, hijacking the machinery to copy itself. So they inserted a gene in the measles virus that encodes for a fluorescent protein and introduced the modified virus into macaques. As the modified virus invades the cells to make copies, its host will light up, letting the scientists track its movement at various stages of the disease.

Everywhere the monkey has lymphoid tissues—which house immune cells—glowing green speckles appeared, twinkling like stars in the night sky. These winks of light revealed that the virus favors what's known as immune memory cells. These cells record and catalog your lifetime of infections, helping you efficiently battle future invaders on repeat encounters. Later in the infection, the virus also settles into the surface lining of the lungs and nose, which help it launch into the air with each cough.

Once the immune system kicked in to clear the infection, this viral constellation vanished. The sudden darkness highlighted an important step of immune amnesia: By infecting memory cells, the virus not only wiped out some of the body's immune recollections, it essentially turned the system against itself by forcing healthy immune cells to kill off their infected comrades.

“If the virus didn’t kill those memory cells already, the immune system would finish the job off,” de Swart says. “We could literally see it happening under our hands.”

The team later confirmed that a similar mechanism is likely at play in humans. But it's unclear exactly how much immune memory vanished; that probably varies from person to person, de Swart notes. Still, the process emphasizes why secondary disease is so common with measles: Not only does the virus assault the immune system's first line of defense and damage your skin, respiratory, and gastrointestinal tract, it also erases your other hard-won resistances.

Lingering effects

For Mina, the monkey's glowing innards raised a nagging question: “If measles is essentially chewing up all of our immune cells, does that have a long-term impact on our immune memory?”

In a 2015 Science study, Mina and his colleagues tried to tackle this question by turning to massive data sets from the United States, Denmark, England, and Wales from before and after widespread vaccination began in the 1960s. The analysis revealed that declines in childhood disease were stark. In general, when measles was flourishing in unvaccinated populations, up to half of all childhood deaths from infectious disease could be explained by non-measles infection that occur following illness with measles.

What's more, the effects lingered. At any given time, the best predictor of non-measles deaths was the total number of measles cases during the prior three years, Mina explains. This suggests that kids with measles still had a higher risk of death from infections three years later. But these temporal relationships can only tell the scientists so much.

“At the end of the day, that's all epidemiological associations,” Mina notes. “You have to drill into the biology.”

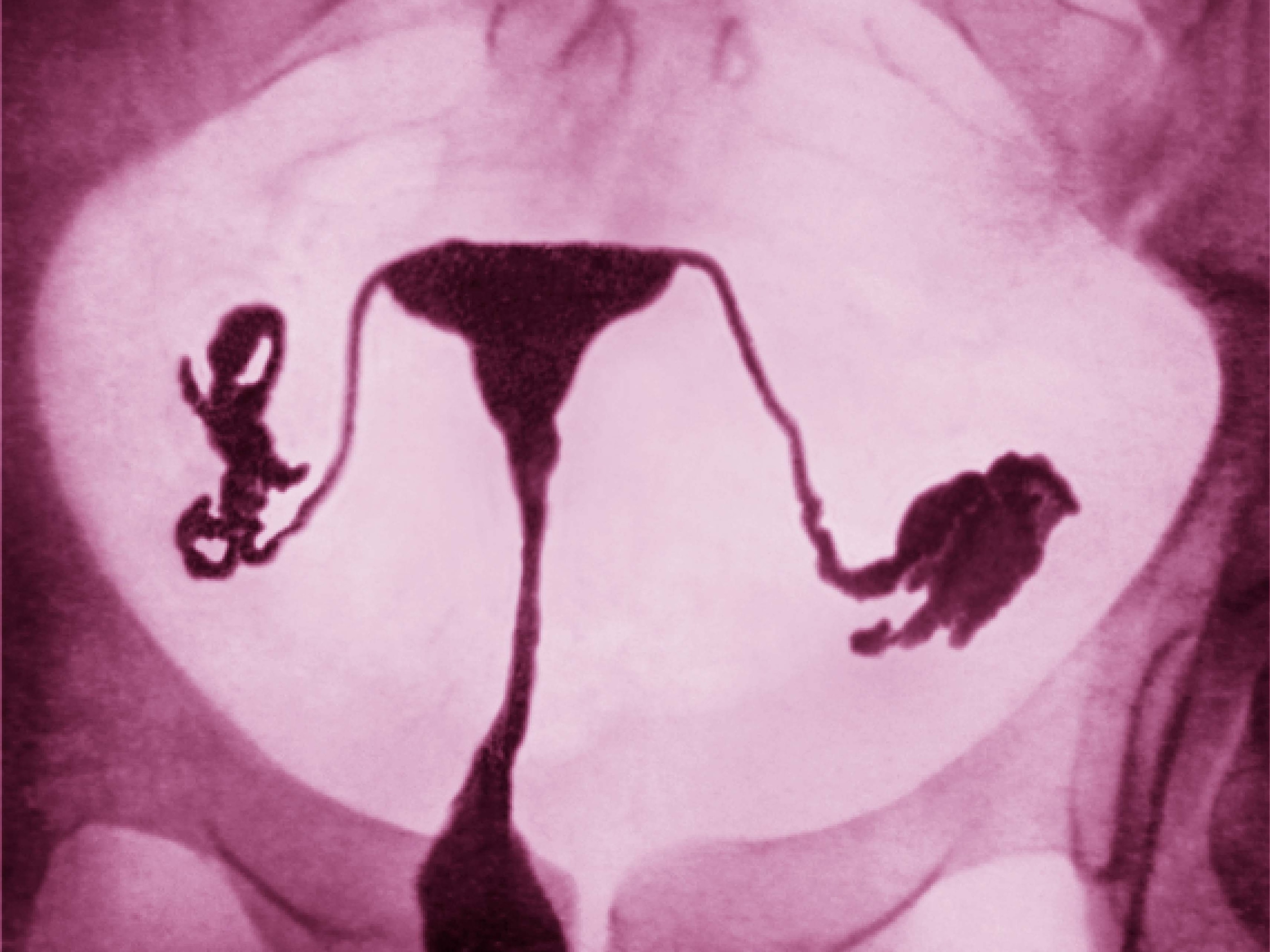

That’s where the latest pair of studies comes in, helping to reveal some of the many intricacies behind the viral attack. For this new work, the researchers studied unvaccinated children between four and 17 years old who attend Orthodox Protestant schools in the Netherlands. They sampled the students’ blood before catching measles and then again after a measles outbreak in 2013.

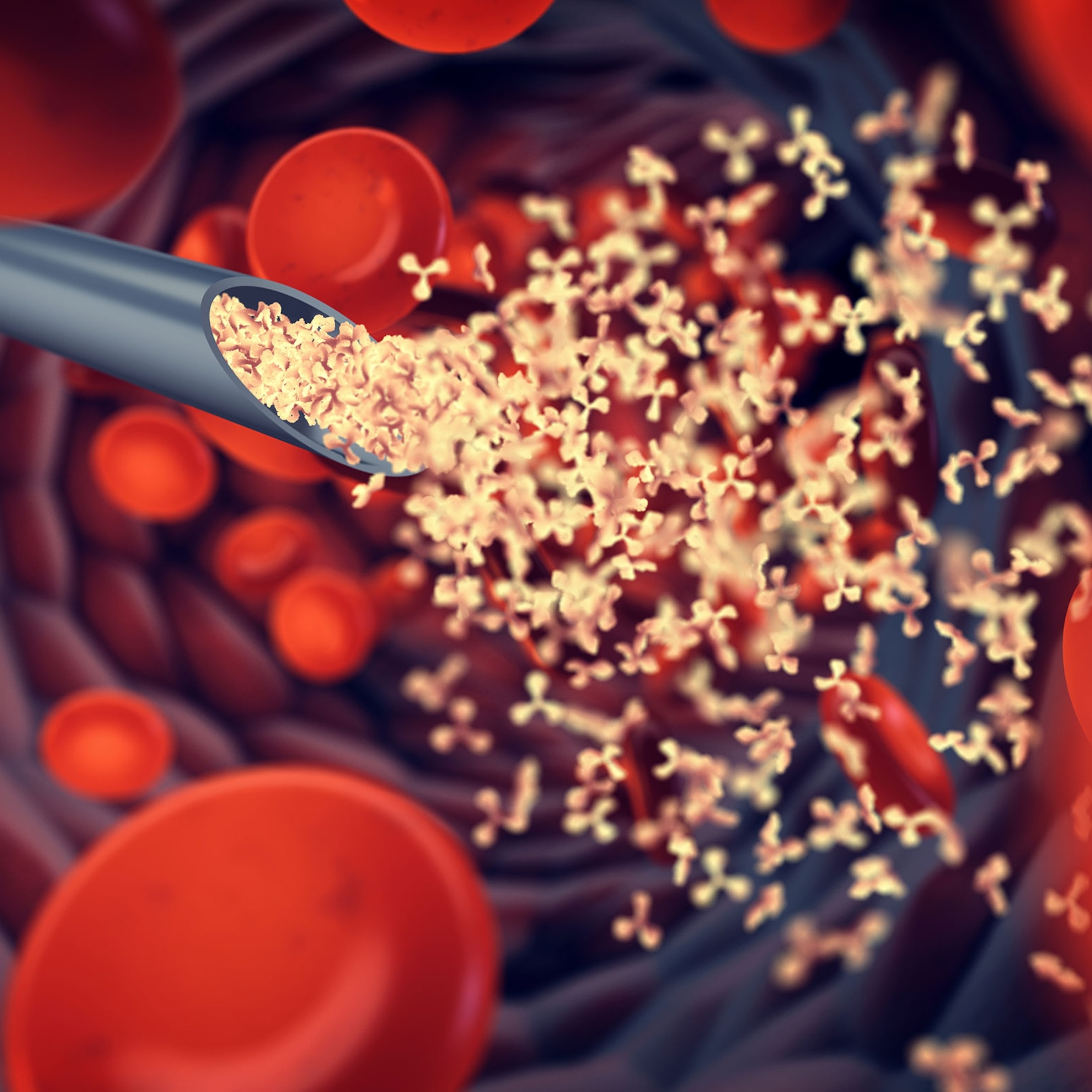

The Science Immunology study examined the blood’s B cells, a primary type of immune cell that can identify invaders and trigger attacks. Some B cells are equipped to fight specific invaders, while some remain “naive,” awaiting instruction on what to target. The analysis revealed that after infection, the army of B cells did not immediately bounce back, losing both naive and targeted fighters.

“This is a virus that doesn’t stop at borders.”Rik de Swart, Erasmus University Medical Center

The Science study used a new method to catalog the antibodies, or invader-neutralizing proteins, in blood samples. The analysis revealed that measles sparked a decline in the antibody array by 11 to 73 percent around two months after the measles infection, severely hindering the immune system’s ability to cope. Re-exposure to viruses and other invaders helped repopulate the lost antibodies.

Global spread

So could secondary infections affect people who currently have measles in the United States?

“I absolutely think so,” Mina says, though he emphasizes that the U.S. healthcare system is strong enough to treat these infections and prevent most of them from turning deadly.

That isn't the case in many developing regions, where something as seemingly mild as diarrhea can kill. And because the virus attacks the immune system, the severity of infections depends on the general health of the population. In essence, measles acts like an infection amplifier, turning up the volume of background disease. This means that in resource-limited areas, the virus will cause higher overall death rates.

“In lots of developing countries still today, we see one in 50 or one in a hundred kids still dying from measles, primarily due to these sort of immune effects,” Mina says. To make matters worse, measles is contagious long before those infected even know it, making it easy for the virus to tag along if its unwitting hosts take to traveling.

“This is a virus that doesn’t stop at borders,” de Swart says, referencing a famous saying: “You cannot stop measles anywhere if you don’t stop it everywhere.”