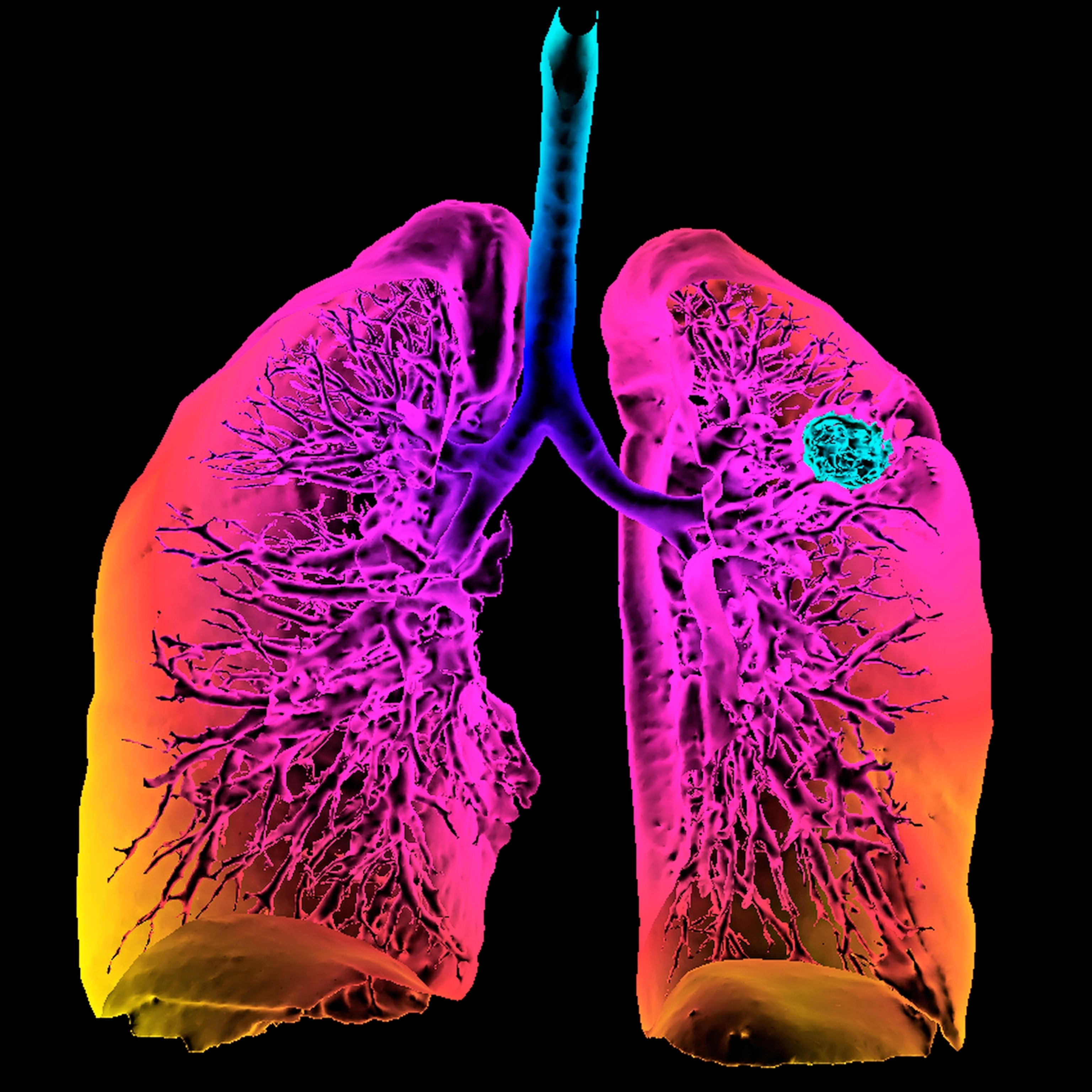

There’s new guidance on lung cancer screening. Here’s who is affected.

The new guidelines recommend cancer screenings even if smokers quit decades ago. That’s because early detection and new therapies can boost survival.

Lung cancer kills more Americans than any other cancer, and an estimated quarter million people are expected to be diagnosed with it this year. Survival rates vary dramatically based on whether the disease has spread, which is why last week the American Cancer Society changed its guidance on lung cancer screening, urging most current and former smokers ages 50 to 80 to get a screening test each year, regardless of how long ago they may have quit.

The more expansive approach is expected to bring in more women, Hispanics, Asians, Indigenous people, and African Americans, who are more likely to be diagnosed in later stages of the disease. If widely adopted, these extra screenings would save thousands of lives. (It does not include the growing number of people who develop lung cancer without smoking.)

“The older guidance was more restrictive, and we were missing a lot of cancers, especially those at the earliest stages when it’s more curable,” says Christina Annunziata, a senior vice president at the American Cancer Society. Medicare, Medicaid, and insurance companies are expected to expand the number of people covered based on the new guidance, she says.

That screening works was reinforced in a study published this week in the journal Radiology. Researchers tracked 1,200 lung cancer patients who were diagnosed following a screening, and found 80 percent were still alive 20 years later. Yet the nation’s current five-year survival rate is 25 percent, according to a 2022 report by the nonprofit American Lung Association, largely because many receive late diagnoses after symptoms appear.

Despite this, only 6 percent of previously eligible patients actually received lung cancer screenings, the lung association found.

The new guidelines will include millions more people. They will cover people ages 50 to 80 who smoked for “20 pack years,” which means inhaling two packs a day for 10 years or one pack daily for 20 years, and the like. Prior Cancer Society guidance called for testing people ages 55 to 74 who smoked for 30 pack years.

Perhaps most important, the new screening protocol recommends screenings regardless of when, or whether, a person stopped smoking—a change from prior guidance that considered people who quit more than 15 years ago no longer at heightened risk for lung cancer. In updating their screening guidance, the Cancer Society undertook a review of the scientific literature and found that, especially for women and Blacks, the risk of getting cancer after quitting still remains elevated two or even three decades later.

“Once you stop smoking the risk levels out rather than continuing to increase exponentially like it does when you haven’t quit, but it still exists,” says Claudia Henschke, the director of the lung cancer screening program at Mt. Sinai Health Systems in New York and a coauthor of the Radiology study.

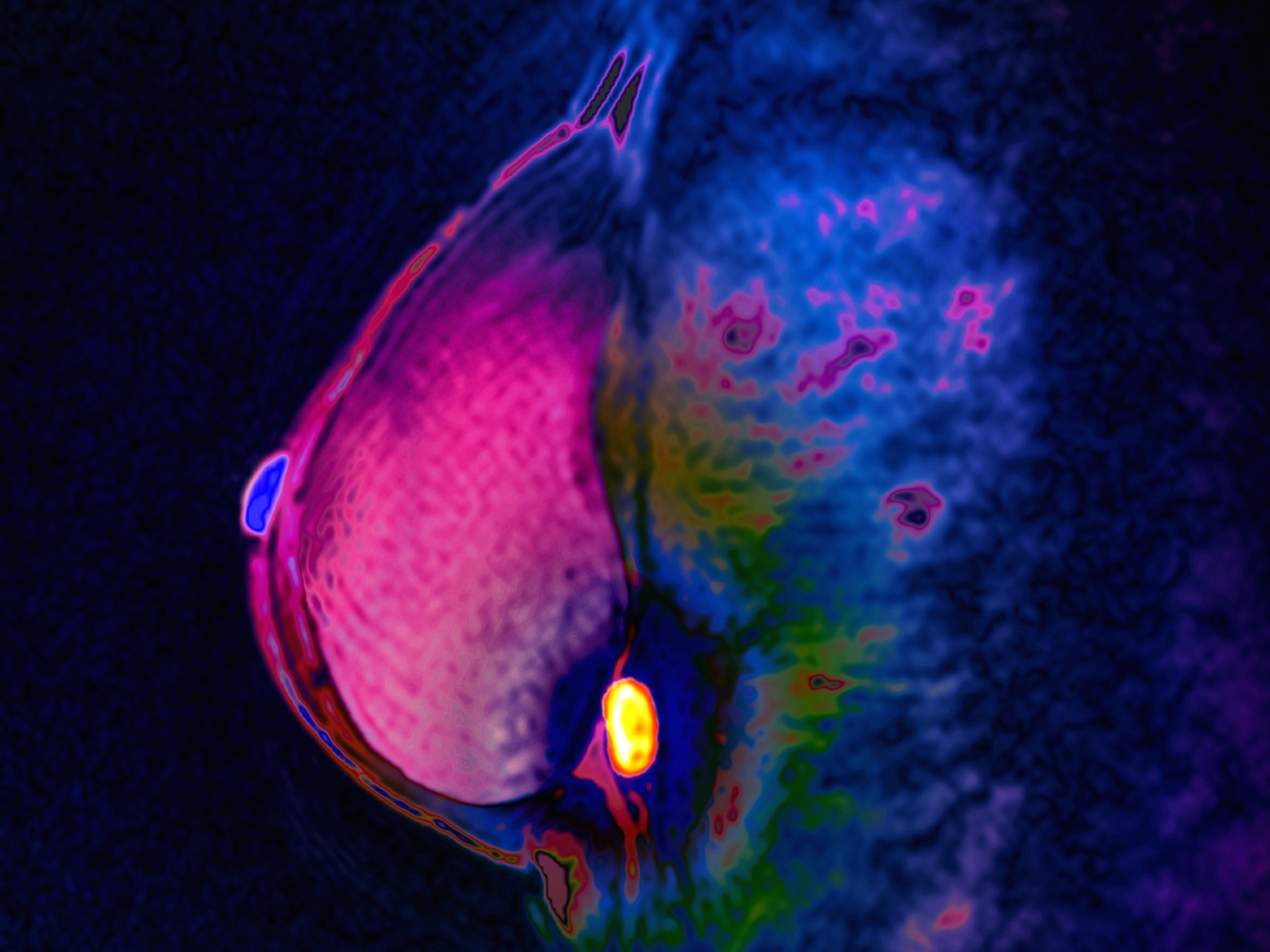

Some people worry about radiation exposure from an annual screen, but the test uses low-dose computed tomography, which has one-fifth the dose of a conventional CT, says Daniel Boffa, the division chief of thoracic surgery at the Yale Cancer Center.

Early diagnosis, new treatments save lives

Early diagnosis of any cancer is important, but this is especially true for lung cancer, which is extremely aggressive and deadly once it spreads, Boffa says.

Massachusetts has the highest rate of screening, at 16 percent of eligible citizens, the lung association found. In some states, including California and Nevada, the figure is closer to 1 percent.

Minorities are especially lagging. Blacks, Latinos, Indigenous Americans and Asians are 13 to 16 percent less likely than whites to have their lung cancer diagnosed early. They are also about a quarter less likely to survive five years. Blacks with low incomes or without health insurance are especially prone to being diagnosed in a late stage of disease.

Some people avoid screening because they fear getting a positive result, which they associate with a death sentence, Boffa says. But treatment advances, including targeted and immunotherapies and minimally invasive surgery, make survival much more likely. For a tumor smaller than two centimeters, surgeons can remove less lung tissue than previously thought with the same survival results, scientists reported earlier this year.

People who have a strong tobacco addiction may worry they’ll have to quit before starting a screening program. “There are considerable benefits to health and quality of life from quitting, but it’s not a requirement for screening,” Boffa says.

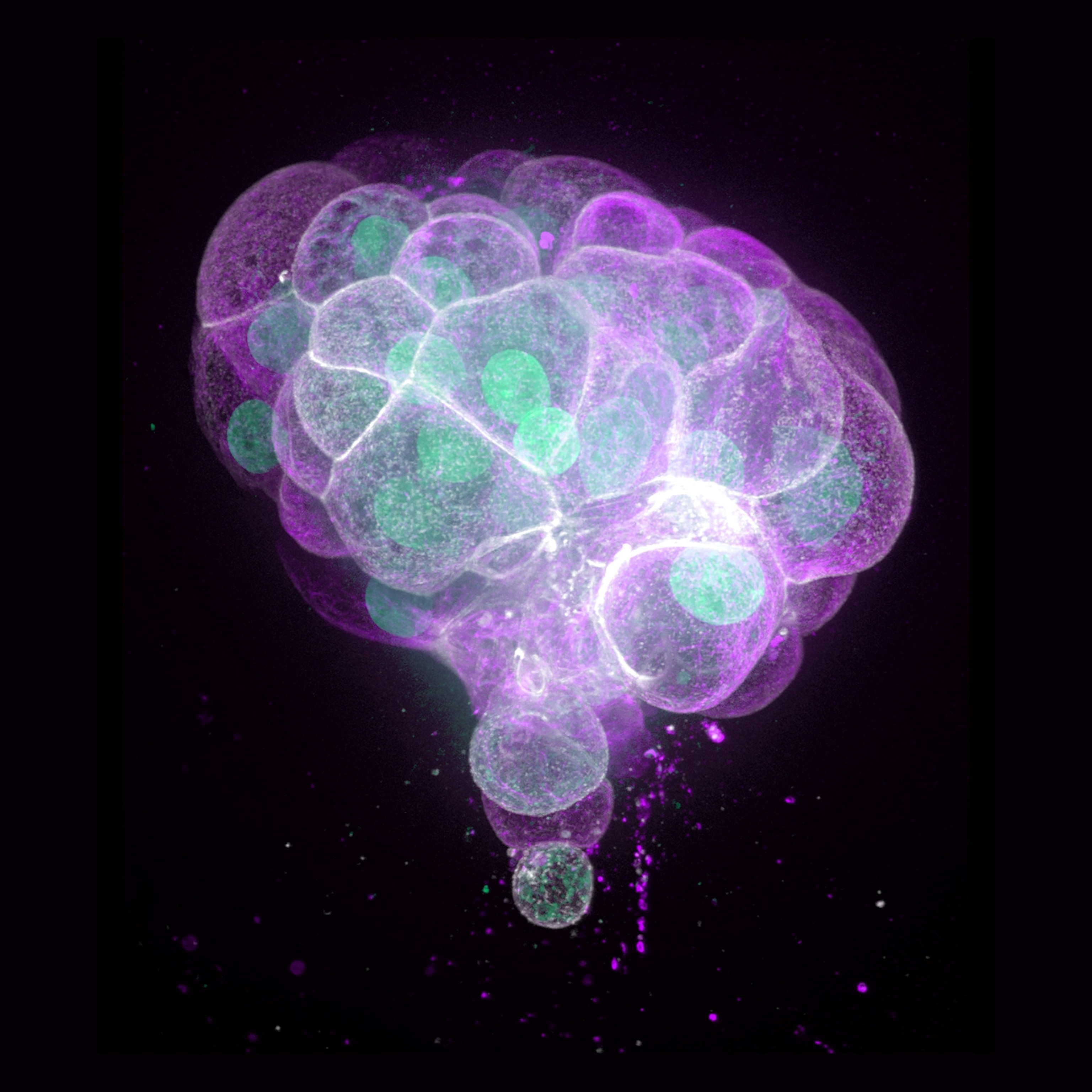

(Read about How liquid biopsies have made it easier to treat cancer.)

The new guidance doesn’t include the growing number of people—some 10 to 20 percent according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—who develop lung cancer without ever smoking. Henschke would like to see everyone age 50 and over checked annually, the way women over 40 have regular mammograms. But the American Cancer Society and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which has slightly different recommendations than the society does, doesn’t think the evidence for this is strong enough.

For now, everyone 50 and older with a history of smoking should talk to their physician about arranging a screen, this year and every year going forward.

“The reality of screening is it really works,” Boffa says. “It’s the most important tool that we have for reducing a person’s chance of dying from lung cancer.”