This rare disorder is a leading cause of blindness in young people

Here’s what to know about the irreversible eye disease at the center of the new National Geographic documentary Blink.

Edith and Sébastien Pelletier’s lives were overturned in 2019 with the news that three out of their four young children have a rare and irreversible eye disorder that usually leads to blindness.

They began preparing their children by teaching them the skills they'd need to navigate life without sight—and by taking them on a journey around the world "to fill their visual memory with...beautiful things" before the condition worsens. This journey was documented in the new National Geographic film, Blink, which is now streaming on Disney+.

The disease the Pelletier children have is known as retinitis pigmentosa, an incurable condition that affects about one in 4,000 people in the United States and is the leading cause of visual disability and blindness in people under 60.

(Why are so many children being diagnosed with myopia?)

While it affects families in many ways, "it's the severity of the disease combined with the lack of treatment that makes the situation so desperate for patients," says Henry Klassen, an ophthalmologist and director of the Stem Cell & Retinal Regeneration program at the University of California, Irvine, who is conducting multiple clinical trials to find a treatment for the disorder.

Here's what retinitis pigmentosa is, what causes it, and whether there is anything that can be done to prevent or treat it.

What is retinitis pigmentosa?

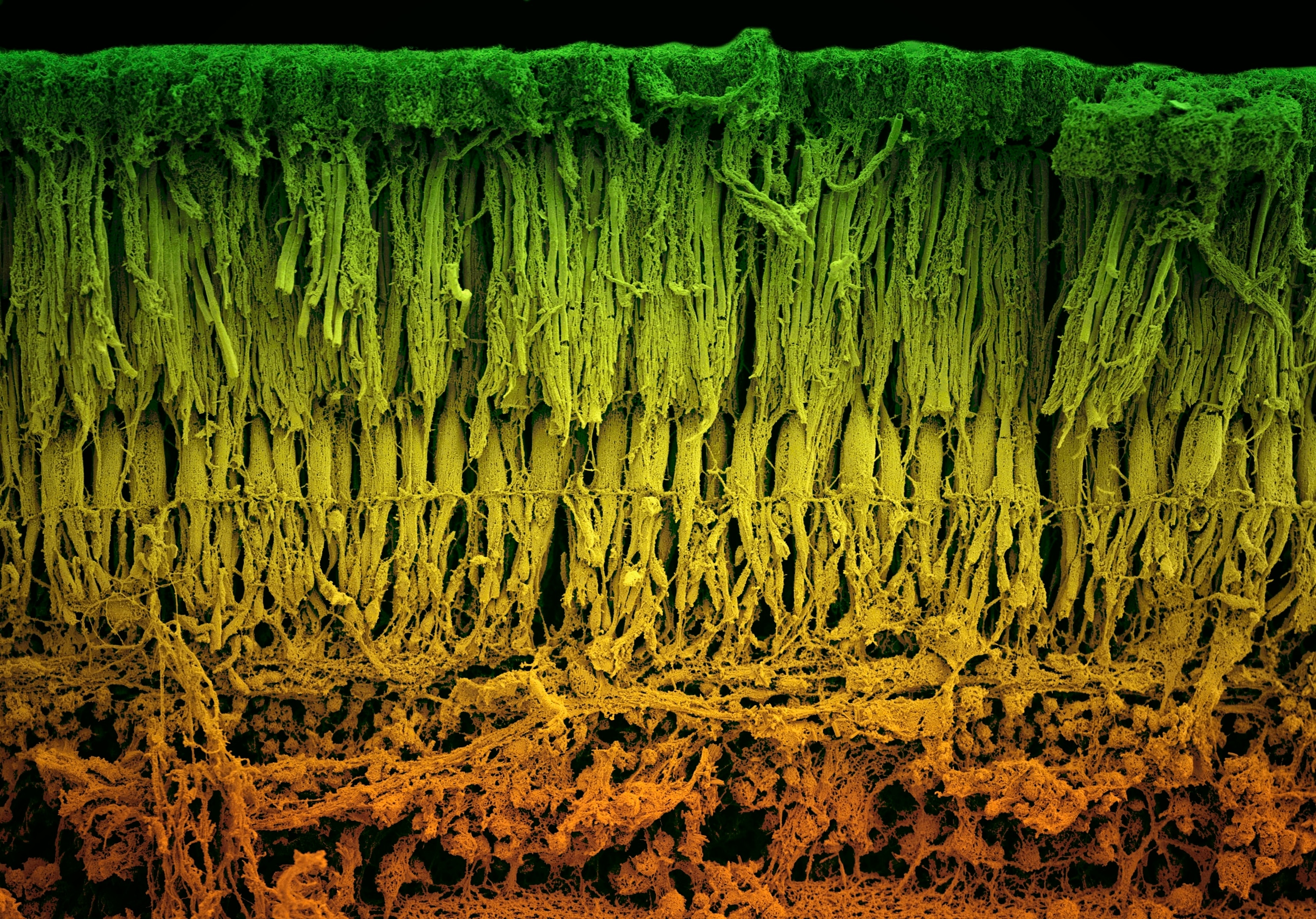

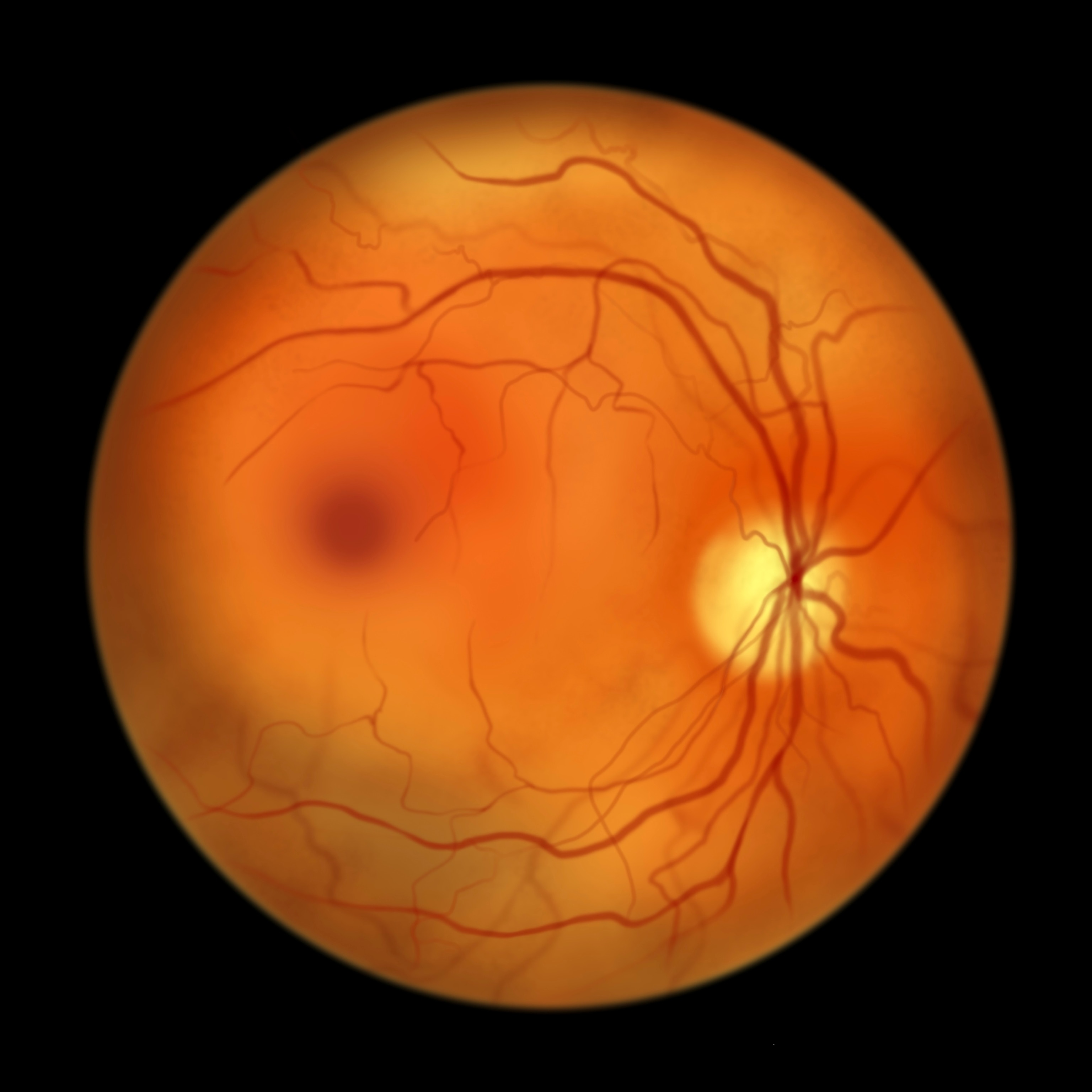

Though many people think of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) as a singular disorder, it's actually a group of rare eye disorders—all of which affect the light-sensitive layer of tissue in the back of the eye known as the retina.

This layer of tissue is made up of cells called photoreceptors, which are responsible for everything we see.

"Photoreceptors are the key to collecting the light that comes into the eye and sending it to the brain to form our vision," says Laura Di Meglio, an instructor of ophthalmology at the Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. She explains that there are two types of photoreceptors: rods and cones. Rods help with night and peripheral vision while cones facilitate central vision and help us see in color.

(How eyes make sense of the world.)

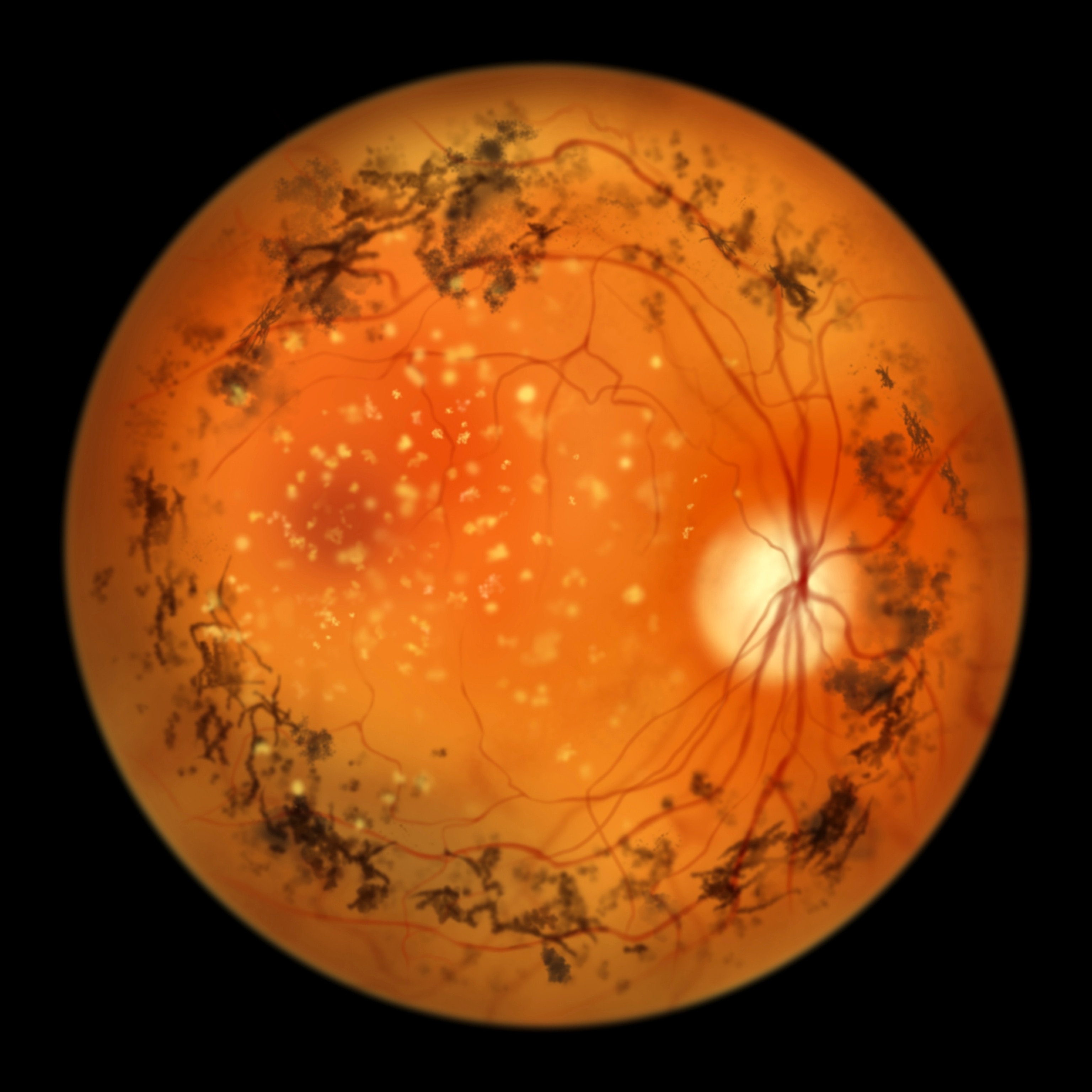

When someone experiences RP, their rods are usually affected first, which is why an early sign of the disease is struggling to see at night. Another sign is bumping into things on one's side—caused by lost peripheral vision. Once cone cells begin to deteriorate as well, the person may experience color blindness and often eventually loses their sight completely.

Because it's progressive in nature, RP isn’t often diagnosed until a child is at least 10—though it's not uncommon for it to be diagnosed earlier or for its discovery to be missed until one's 20s, 30s, or even 50s.

"Even if you can see quite well earlier in life, the loss of vision related to RP is so relentless that, bit by bit, all ability to see can ultimately be lost," says Klassen.

What causes retinitis pigmentosa?

While the U.S. National Eye Institute notes that RP can be caused by factors such as infections, medication, or eye injuries, the disease is most commonly something you’re born with.

This is because RP is caused by mutations in the genes that control cells in the retina. And it’s not just a single gene that’s the culprit. Instead, "mutations in as many as a hundred different genes cause RP," explains Vinit Mahajan, a retina specialist and the vice chair for research at Stanford University’s Byers Eye Institute.

(What life is like when your brain can't recognize faces.)

Nor is a single type of mutation responsible as variations within each gene can also lead to the disease. Because of such factors, more than 3,100 different mutations have been identified as contributing to RP.

Even still, Mahajan notes that not every family member of an affected person will develop RP. Genetic testing is recommended to know for sure.

Who is more likely to have retinitis pigmentosa?

The inherited nature of the disease is also why RP is more common in cultures where there is a smaller gene pool and therefore higher instances of marriages between distant relatives.

This is one reason research shows genetic disorders being more common in certain South Asian populations, for example. "South India also has a higher incidence of RP—one in 930—and China has an incidence of one in 1,000," says John Galanis, an ophthalmologist in St. Louis, Missouri.

(Can trauma be inherited through genes?)

Despite such associations, "there is not necessarily any predilection of RP in any race or ethnicity," says Marc Mathias, an associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. "It can affect anyone, anywhere."

Why isn't retinitis pigmentosa preventable or treatable?

One of the most challenging aspects of RP is that it can't usually be prevented or treated. This is due to the enormous number of gene mutations that cause the disease and the fact that the retina is part of the central nervous system, "which lacks regenerative capacity in humans," says Klassen. In other words, once the cells die, they do not grow back.

In some cases, Mathias adds, it’s not even possible to identify the gene that’s causing the disease.

However, he says that decades of extensive research aimed at treating RP are beginning to pay off.

Is hope on the horizon?

Recent advancements in gene therapy, for instance, have given scientists hope for finding treatment. The U.S. Food & Drug Administration notes that gene therapy may involve replacing a disease-causing gene with a healthy copy of the gene; destroying a problematic gene; or introducing a new or modified gene to help treat the disease.

These forms of gene therapy are at the center of dozens of RP-related clinical trials—and one therapy has already been FDA approved. Called Luxurtna, it targets only two specific gene abnormalities related to RP—meaning it can only help a subpopulation of about 0.3 to 1 percent of all RP patients, explains Galanis.

A number of studies from the late ‘90s and early 2000s also suggested that vitamin A and supplements like fish oil and lutein may help prevent RP—but Galanis says these studies were correlational and not causal. Mathias agrees, but notes that there is currently at least one promising ongoing clinical trial, which is looking at whether a powerful antioxidant, called N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), "may slow down cone cell loss in patients with RP."

Beyond such advancements and interventions, Mathias says degeneration can at least be slowed by maintaining strong retinal health—which involves eating healthy, exercising, avoiding smoking, and wearing protective eyewear when out in the sun.

Ninel Gregori, a Miami-based ophthalmologist and the spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology, says that early detection can also help RP patients stay independent longer. She adds that supportive treatment such as orientation and mobility training and psychological support can also be helpful.

As for new frontiers of research, Mahajan says genetic testing capabilities have vastly improved and that scientists are researching many innovative therapies such as additional gene therapies, small molecule drugs, retinal cell transplants, and electronic-support devices.

"While research takes time," says Mathias, "the future is bright and the hope for more RP treatments is driven by dedicated researchers and an industry continually striving to save sight."