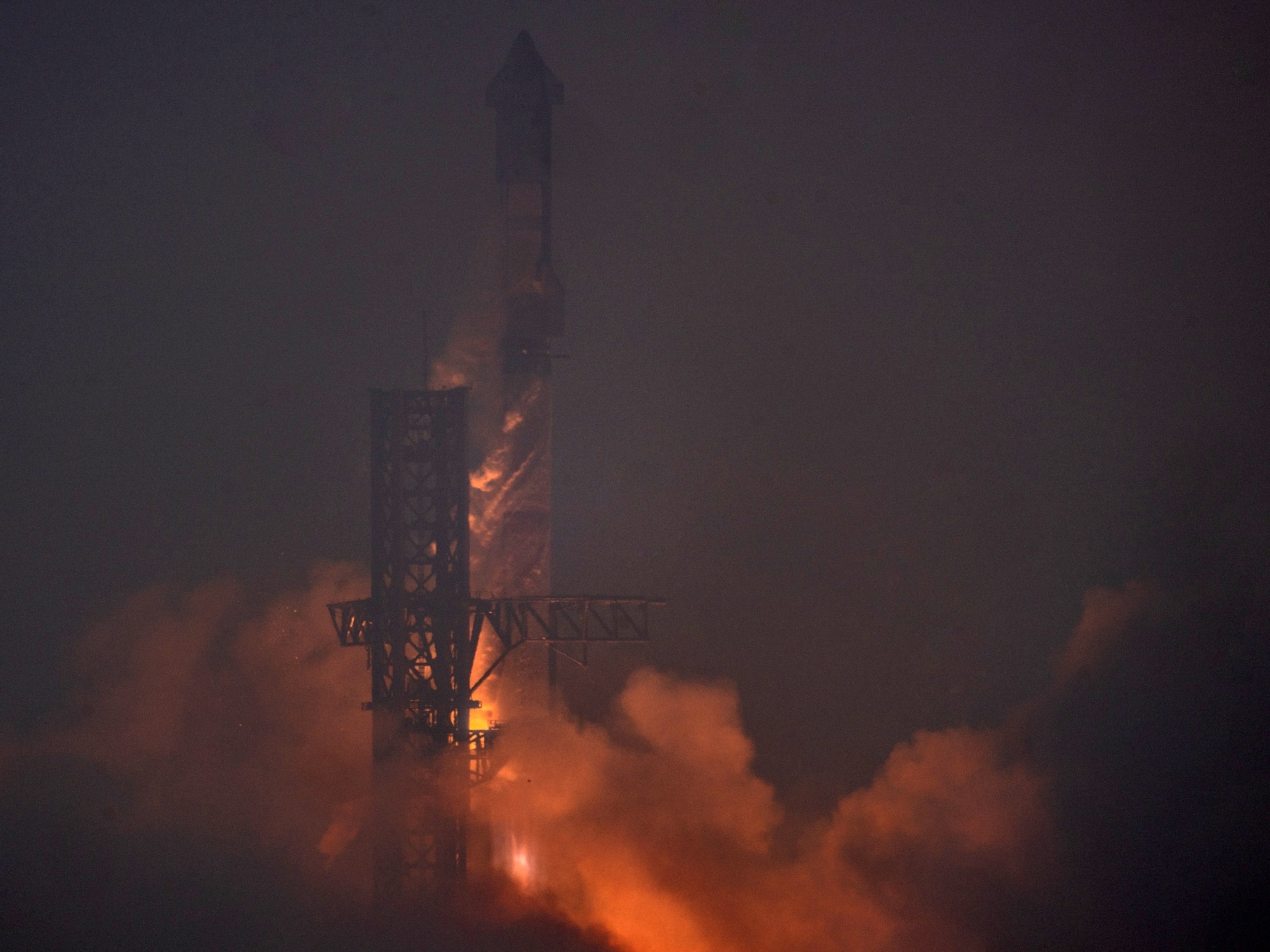

In the the pre-dawn hours at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, after a one-day delay caused by high winds, SpaceX successfully launched humans into space from U.S. shores for the third time in less than a year.

But this time, the astronauts sailed into orbit atop a reused Falcon 9 rocket booster—the same booster that sent the Crew-1 mission to the International Space Station last November. They are also riding aboard a used spacecraft: the same Dragon capsule, called Endeavour, that NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley flew during their Demo-2 test flight last May. On that mission, Behnken and Hurley became the first humans to launch from Cape Canaveral since the end of the U.S. space shuttle era.

“It’s kind of exciting to see all those three missions in that one vehicle,” Steve Stich, NASA’s Commercial Crew Program manager, told reporters before launch.

Now the Crew-2 astronauts—all veteran space flyers—are settling in for their roughly 24-hour cruise to the station, where they’ll live for six months. The four-person crew is made up of NASA’s Shane Kimbrough and Megan McArthur, European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Thomas Pesquet, and Akihiko Hoshide of the Japan Aerospace and Exploration Agency (JAXA). More than 200 science experiments are also aboard, including several that will investigate human immune cell function.

Late last week, when the crew arrived at Kennedy Space Center, they were treated to a view of their rocket as their plane descended.

“There’s nothing like it, when you look out the window and see a spaceship getting prepared and realize that you’re going to be riding on it in a few days,” McArthur, who was rocking a pair of sparkly silver boots, told reporters after they arrived.

“Flight proven”

Both NASA and SpaceX contend that reusable spacecraft are crucial for making space travel more affordable. The concept is not new; for years, the space agency reused its small fleet of space shuttles, but reusable rockets weren’t a reality until SpaceX entered the scene.

In December 2015, the company successfully returned a Falcon 9 rocket booster to its landing pad for the first time. Since then, it has achieved 80 rocket landings, both on land and on barges at sea, although the company’s boosters still occasionally miss their mark.

Among roughly two dozen reused boosters in the company’s inventory, the most flown is booster B1051, which has so far survived nine uncrewed launches and recoveries. SpaceX says that the latest iterations of its Falcon 9 boosters, known as Block 5, are designed to survive at least 10 launches—and Benji Reed, SpaceX’s senior director of human spaceflight programs, says the company intends to push that limit for uncrewed missions.

That equation changes when humans are involved.

“This business of human spaceflight is unforgiving,” Norm Knight, NASA’s deputy manager of flight operations, said at a pre-flight press event.

The SpaceX crewed Dragon capsules are designed to fly at least five times each, with some refurbishment between journeys. But before certifying the rocket and spacecraft for the Crew-2 flight, engineers scrutinized every aspect of the hardware, looking for any defects or surprises. During the process, they learned from teams at SpaceX’s Texas facility that the company has been routinely loading extra liquid oxygen fuel into Falcon 9 boosters—the equivalent of 2,500 to 3,000 pounds of fuel, Stich said. But that’s a tiny percentage of the total launch weight, and NASA and SpaceX decided that the overage didn’t pose a threat to the astronauts.

“We ask ourselves all the time, would we be willing to fly our families on these vehicles?” Reed said. “I know there’s a little boy out there whose mom is flying. This is something we pay a lot of attention to.”

The Crew-2 booster, which teams refer to as “flight proven,” last flew in November, and its sooty façade bears the markings of its previous journey into space. It also offered the Crew-2 astronauts a chance to commemorate their flight.

“We were lucky enough to draw our initials in the soot on the side of the rocket,” Pesquet said. “I don’t know if this is going to stick, but it’s really cool.”

Life on station

For Crew-2, life in orbit will include performing science experiments and space station maintenance—and for the first couple of days, it’s going to be a bit cramped up there. The Crew-1 mission’s four astronauts are still on board, as are three astronauts who arrived April 12 on a Russian Soyuz capsule.

To accommodate the 11 inhabitants, managers increased the capacity of the station’s life support systems, such as those that remove carbon dioxide from the air, and crews are setting up temporary sleeping spaces. Living quarters should be a bit roomier after April 28, when Crew-1 is scheduled to depart.

McArthur, who will be piloting the same spacecraft that her husband, Bob Behnken, flew during the Demo-2 flight last year, said that she’s picked up a few things from Behnken about flying the Dragon capsule—and even more about living on the station for an extended period, especially when it comes to meals.

“He really told me, Hey, variety is going to be key—get hot sauces and different flavors and things you’ll be able to share with your crewmates,” she said. Similarly, both Pesquet and Hoshide promise that they’ve brought special meals to the station so that the crew can enjoy some French and Japanese cuisines, although Hoshide lamented the lack of sushi.

“I think some of the French cheese is actually not legal on the ISS,” Pesquet joked. “I’ve had some national pressure to bring some good stuff, and also from my crewmates—they were like, OK, we’re flying with a Frenchman, it better be good.”

In between meals, the Crew-2 astronauts will be working through more than 200 research experiments—a scientific to-do list that’s only possible because of the increased number of astronauts in orbit.

“We didn’t want crew time to continue to be our limiting factor,” David Brady, associate program scientist for the ISS, told reporters during a press call. Now, he says, the number of experiments is limited more by how much mass and volume can be launched to the station.

Among the experiments are a test of edible packing materials to cut down on waste, an update to the station’s solar arrays, a look at how cotton plants respond to limited water availability, and probes of human biology. The microgravity of the space station provides an ideal environment to study how human cells grow, communicate, and adapt.

“We don’t fully understand why, but in microgravity, cell-to-cell communication works differently than it does in a two-dimensional cell culture flask here on Earth,” Liz Warren, senior program director at the ISS U.S. National Laboratory, told reporters. “Cells aggregate or gather differently in microgravity. They gather in a more 3D way. They behave more like they do when they’re inside the body.”

Investigators are focusing on lung tissues, retinal implants, engineered skeletal muscle, kidney stones, and the immune system—which has been an international research priority since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

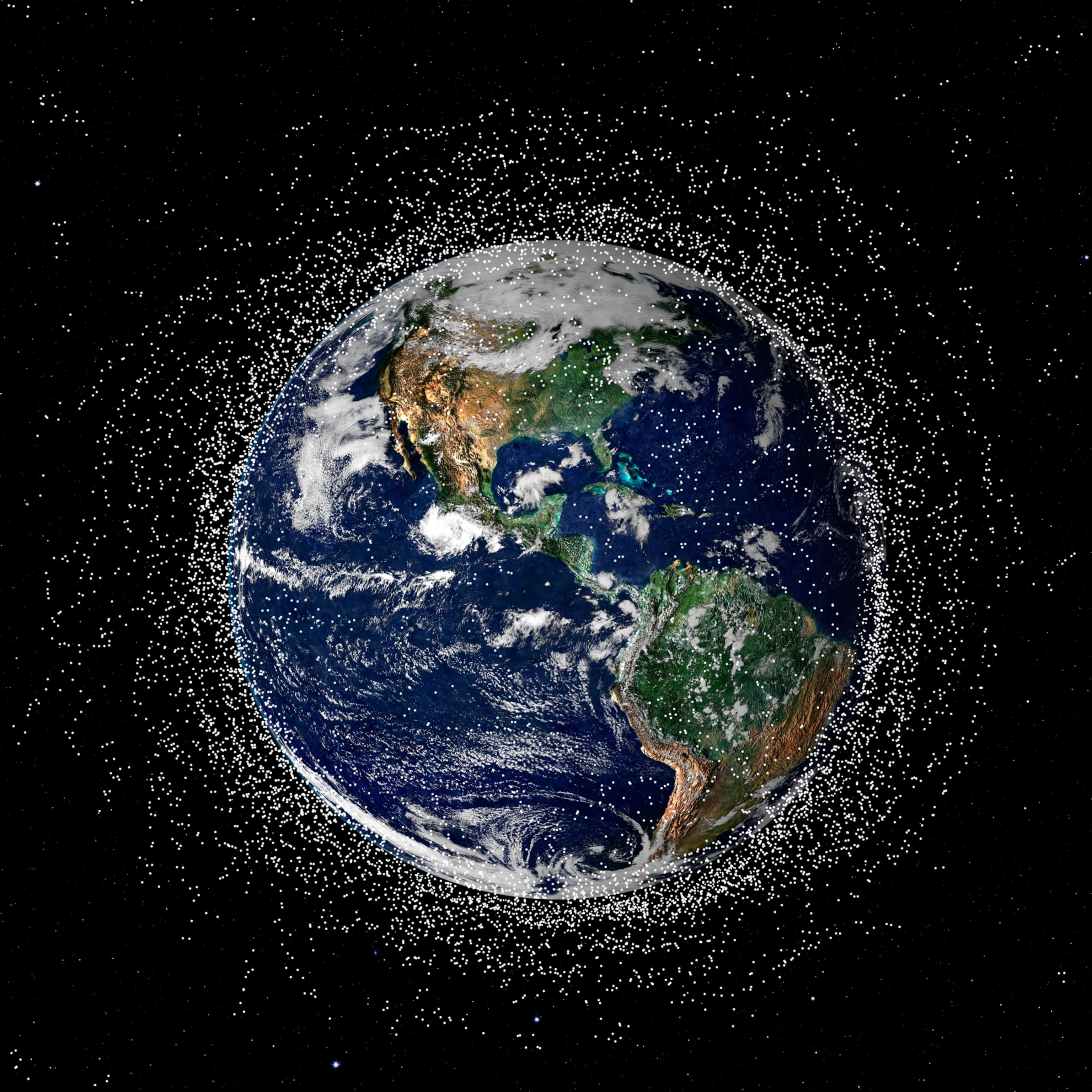

A number of Earth-observing experiments are also planned, including continued photographic documentation of our cloudy, watery world. So far, astronauts have snapped more than 1.5 million photos of Earth from space, and the space station’s new occupants will be adding their own imagery to that total.

“We’ve got many investigations on board the spacecraft looking down at Earth,” Kirt Costello, ISS chief scientist, said before the launch. “We also have the crew, who have the best seat in the house.”