How drugs like Wegovy might affect kids in the long term

The number of teens and young adults taking GLP-1 drugs has increased by 594 percent—but scientists are still trying to understand the long-term effects.

Fifteen-year-old Jenny Arrellin has struggled for years to lose weight through diet and exercise because of her polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a complex hormonal and metabolic disorder that’s associated with excess weight and insulin resistance. Knowing she was at risk of developing type 2 diabetes, in March 2024 she decided to participate in a study of Wegovy, a GLP-1 receptor agonist drug similar to Ozempic.

The drug curbed her appetite considerably and changed her taste in foods—“I stopped liking pizza and chips and now I don’t like candy at all,” she says. It also eliminated the food noise she used to get when she was bored. But "the biggest change is I don't eat nearly as much as I used to," she adds.

(Can’t stop thinking about your next meal? That’s "food noise.")

Now that drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Zepbound have led to major weight-loss success among adults, there’s growing interest among kids and teens. In fact, the number of teens and young adults taking GLP-1 drugs increased by 594 percent between 2020 and 2023, according to research in a 2024 issue of JAMA Network.

While Ozempic is not approved for use in kids, Wegovy is approved for weight loss in kids ages 12 and older who have obesity. Research has found that these drugs can help young people with obesity lose substantial amounts of weight, as well as potentially reducing their risk of developing weight-related diseases.

“When kids come to me with obesity, they usually have greater fat mass and more obesity-related diseases such as diabetes, metabolic associated steatotic liver disease [formerly known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease], high cholesterol, hypertension, and orthopedic issues,” says Fatima Cody Stanford, an obesity medicine physician-scientist at Massachusetts General Hospital and an associate professor of medicine and pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. “If you don’t treat [the obesity], they get worse and worse.”

(The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro.)

While these drugs do seem to be effective in adolescents in the short term, “there’s more we don’t know than we do know about using these drugs in children,” says Robert Lustig, a pediatric neuroendocrinologist and an emeritus professor of pediatrics at the University of California San Francisco.

Will kids need to stay on these drugs for life to keep the weight off as most adults do? And how do these drugs affect a body that’s still growing—from brain development to hormonal changes? There are lots of unanswered questions.

Who’s a candidate for these drugs and why

Changing your diet and exercising more isn’t always enough to help people of any age, including kids, lose excess weight. “We know from decades of evidence that the vast majority of people who try to lose weight with lifestyle measures alone achieve modest weight loss at best,” says Bethany R. Cartwright, a pediatric obesity medicine specialist at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

In 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued its first clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with overweight and obesity. In addition to bariatric surgery and certain weight-loss medications, it included the possibility of using GLP-1 receptor agonists.

“If we can help a child lose excess weight before early- to mid-puberty, their chances of getting type 2 diabetes are much less,” says Melanie Cree, an associate professor of pediatric endocrinology at the University of Colorado Anschutz and Children’s Hospital Colorado. This is especially significant, she adds, because “type 2 diabetes is much more aggressive in teenagers than adults.”

(It’s possible to reverse diabetes—and even faster than you think.)

A study in a 2022 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine found that adolescents with obesity or overweight and at least one weight-related coexisting condition (such as type 2 diabetes) who received a once-a-week injection of semaglutide (Wegovy) lost an average of 16 percent of their body weight after 68 weeks. More recently, in a phase three clinical trial, published in a September 2024 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine, an older GLP-1 receptor agonist called liraglutide was found to reduce body mass index by an average of 6 percent in kids ages six to 11 with obesity.

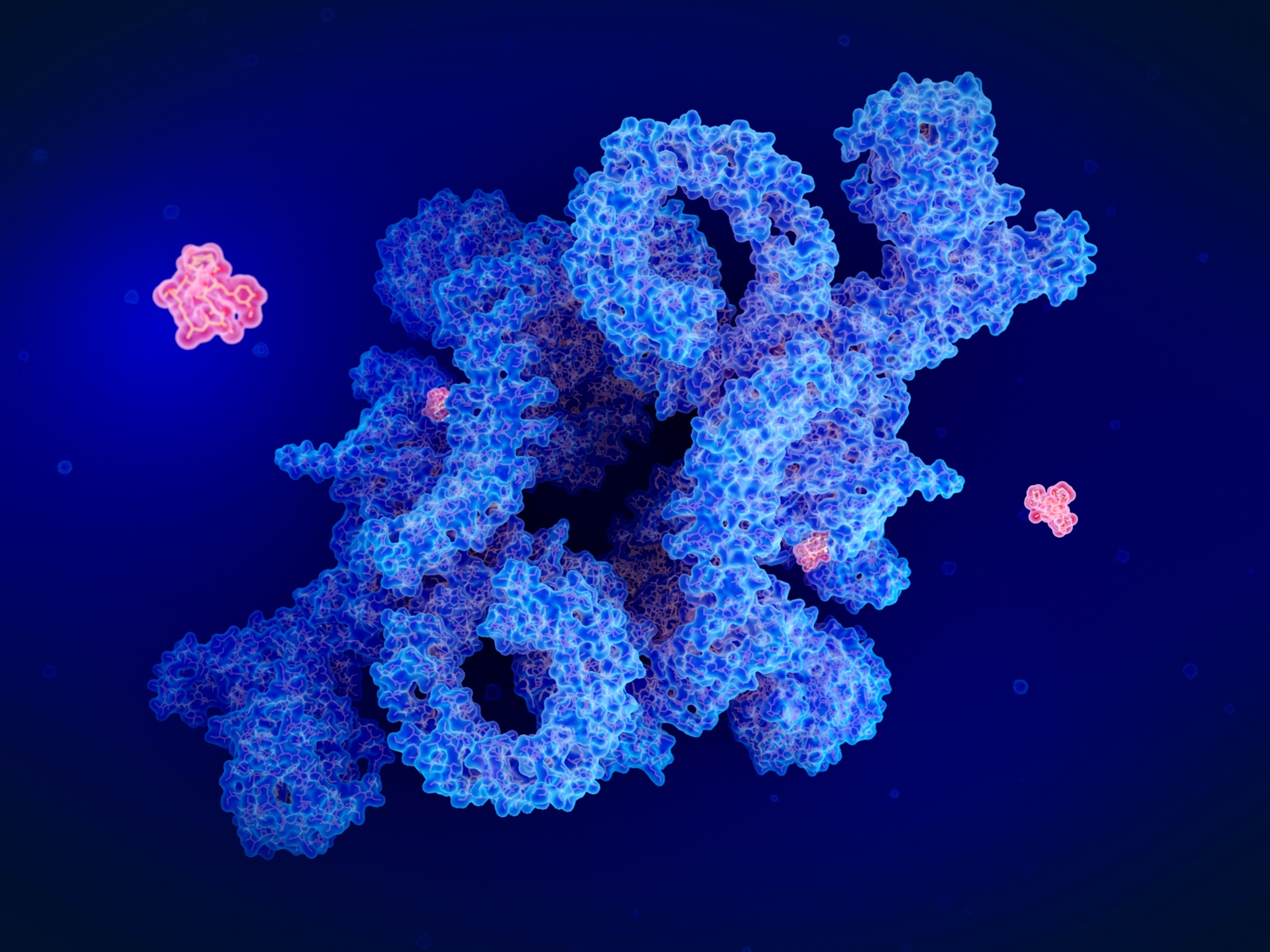

The GLP-1 agonists work the same way in teenagers as they do in adults. “What we’re doing with GLP-1 [agonists] is trying to adjust the hormones the body naturally makes,” explains Caroline M. Apovian, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

These medications stimulate the pancreas to release insulin, which helps reduce blood sugar levels. They also reduce appetite, slow the movement of food through the gastrointestinal tract, and increase feelings of fullness.

After 10 months on Wegovy, Arrellin lost 40 pounds from her 5’2” frame and is now taking Metformin to prevent her from regaining the weight.

“It’s not the easiest to keep off,” says Arrellin, a high school sophomore in Colorado. But so far, she has done it, and she is motivated to avoid regaining the weight. Losing weight “made me happier and gave me more confidence,” she says. “My energy increased, and I don’t get winded anymore when I do things like boxing or playing volleyball.”

Concerns about kids and GLP-1 agonist drugs

But the growing and changing bodies of kids and teens present some unique challenges.

“It’s important to remember that these drugs don’t work in everybody—they don’t work in one in four kids,” says Cree. This may be partly because of the hormonal changes that accompany puberty—and the fact that levels of growth hormone are higher in kids and teens, which can lead to insulin resistance, meaning that “insulin doesn’t work as well and hunger is increased.”

(Girls are going through puberty much earlier. Here's why.)

Because teens experience shifts in their circadian rhythms, they often don’t get enough sleep, which can also increase insulin resistance and hunger.

GLP-1 agonists also influence dopamine pathways in the brain, particularly within the reward system. “There’s a high density of these [GLP-1] receptors in the brain,” says Dan M. Cooper, a professor of pediatrics at the University of California at Irvine.

“We don’t know the long-term consequences of using these drugs in a brain that’s still developing,” Cooper adds. “There seems to be lethargy associated with use of these drugs in adolescents.”

Another lingering question: If someone uses one of these medications throughout their teens, does that permanently change how their brains sense or respond to food or other sources of pleasure? Lustig is concerned that if the brain’s reward system is seriously dampened, it could increase teens’ risk of developing depression. “You need reward—reward is what gets you up in the morning,” he says.

Meanwhile, some doctors are concerned about how use of these drugs during the developmental years could affect kids’ growth and maturation. In a 2023 paper in the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, Cooper and a group of other doctors from the University of California at Irvine raised concerns about how these drugs could affect kids’ physical growth and brain development, their bone-density and muscle mass development, and perhaps increase their risk of developing eating disorders.

It also isn’t clear whether kids will need to continue using these drugs for the rest of their lives. “We generally think of these medications as being best for taking long term,” says Cartwright. “It’s like taking medication for blood pressure—if you stop taking it, blood pressure will go up again.” In this case, the presumption is that appetite will increase and weight gain will result after someone stops taking a GLP-1 agonist.

Research is underway to investigate whether a lower, maintenance dose can help teens maintain their goal weight once they reach it, Cree says. “We need big, long-term studies to get answers to these questions,” she adds. “Any new drug is a long-term experiment. It’s tricky because we worry more [about the long-term effects] in kids but when a medication has a positive effect in kids, we don’t want to withhold it.”

After all, being overweight can affect kids’ mental health, along with their physical health. “Kids with excess weight are often bullied,” Cree says. “What we see is that as kids lose weight, they feel more comfortable with their peers and their moods improve as well.” That’s a multi-layered victory.