We’ve been measuring BMI since the 70s—but is the flawed metric still helpful?

Our body mass index is categorized into underweight, normal, overweight, and obese based on data largely from white middle-aged men—decades ago.

You’ll find it at the doctor’s office, at the gym, and in online calculators: the body mass index, or BMI, has been ever-present since its introduction in the 1970s. But this metric of a “healthy weight” has come under scrutiny in the past decade or so, and with good reason. The relationship between physical well-being and BMI is complicated, and it’s often not a good indicator of your overall health, experts say.

BMI is a simple measurement calculated by dividing a person's weight (or mass in kilograms if using metric) by their height. For decades, clinicians have used BMI to put our weight into different categories: underweight, normal, overweight, or obese. Twenty-five is the magic number: at this number or higher, you fall into the overweight or obese category.

Some population studies have associated having a high BMI with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, and other endocrine disorders. However, it may not be weight alone that plays into these adverse health effects: research shows the shame and stigma people with high BMI face could also contribute to poor health outcomes.

Other studies have failed to find a strong correlation between BMI and health. People who are lean can be unhealthy, and people who have a BMI over 25 can have pristine health markers, says Fatima Stanford, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and obesity medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. So when it comes to the individual, “this metric doesn’t really accurately predict health,” says Janet Tomiyama, a professor of psychology at UCLA.

Why do we still rely on BMI, and are there better metrics of overall health we can use?

Why we haven’t thrown out BMI

The idea of a standardized weight metric was introduced in the 1830s by Belgian statistician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet, who wanted to quantify ideal weight metrics for the “normal man.” Then, in the 1950s, life insurance companies started estimating people’s body fat—and their risk of death—by comparing their weights with the average weights of others of the same height, age, and gender. Finally, in the 1970s, physiologist Ancel Keys published a study of roughly 7,000 healthy, mostly middle-aged white men, creating what we now know as the BMI calculation.

BMI has been revised since to provide different scales for children and teens and adjust the percentiles based on more recent population data, but the basic calculation remains the same—one calculation for both men and women.Also, ranges for underweight, normal, and obese BMIs haven’t been updated in decades.

One reason BMI is still widely used is because it’s a relatively simple measurement to take. This makes the metric easily accessible to practitioners without specialized training, says Eleanna De Filippis, a physician and endocrinologist at the Mayo Clinic.

Stanford says that extremely low or high values of BMI could be an indicator of potential health issues, but values around 25 to 30 are difficult to interpret without other health metrics.

Where BMI falls short

There are big issues with only using BMI to assess health. BMI can’t tell what percentage of a person’s weight is from their fat, muscle, or bone. That’s why muscular athletes often have a high BMI despite having little body fat, De Filippis says. It’s also possible to have poor health measures, like high blood pressure and cholesterol, and be at a “normal” BMI, Stanford says.

In a 2016 study of more than 40,000 people in the United States, researchers compared people’s BMIs with other measures of health like insulin resistance, markers of inflammation and blood pressure, cholesterol, triglyceride, and glucose levels. Nearly half of those classified as overweight and about a quarter of those classified as obese had normal health measures. “34 million Americans who are considered overweight by virtue of their BMI have perfectly pristine health metrics,” says Tomiyama, the lead author of the study.

There are other issues, too. Even though body composition can vary depending on a person’s race, ethnicity, age, and gender, clinicians use the same formula to calculate BMI for all adults—even though it was developed using data primarily from white men. This has led a disproportionate number of people from marginalized groups, particularly Black women, to be mischaracterized as unhealthy.

That’s why a lot of clinicians are moving away from using BMI as a measure of health. Stanford says that whenever she assesses people in her clinic, she doesn’t talk to her patients about BMI or consider it when creating a health plan. “I want to get a health picture of who you are, treat the entire you,” she says.

BMI can contribute to eating and stress

There’s also evidence that simply labeling someone as overweight or obese can be harmful. Tomiyama’s research suggests that when people are stigmatized because of their weight, it causes levels of their stress hormone cortisol to spike, which drives appetite. It triggers a “vicious cycle” of eating and stress, she says.

Cortisol can also have negative impacts on most systems of the body, including your heart and organs. Additionally, many patients diagnosed as overweight or obese report having their symptoms ignored at the doctor’s office, she adds.

As to how much negative stigma and stress contributes to the association between obesity and poor health outcomes, researchers say there haven’t been any studies that have looked at that question. “It’s a good question,” Tomiyama says. “But there’s not really an answer.”

The future of BMI

Stanford says that if you’re concerned about your weight, your waist circumference or hip-to-waist ratio might be a better health indicator. Excess central adiposity (fat that’s carried in the midsection) regardless of weight, is the kind of fat that’s most strongly associated with negative health outcomes like cardiovascular disease.

So, a better measure might be body roundness index (BRI), which adds waist circumference to the height and weight calculations of BMI to estimate visceral fat and total body fat percentages. BRI was found to be superior over other measurements in estimating the risk for conditions including heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, and cancer. A recent study found that over a 20-year period, both the lowest and highest BRI groups were significantly more at risk of dying, which the authors argue provide evidence for using BRI as a noninvasive screening tool for mortality risk estimation.

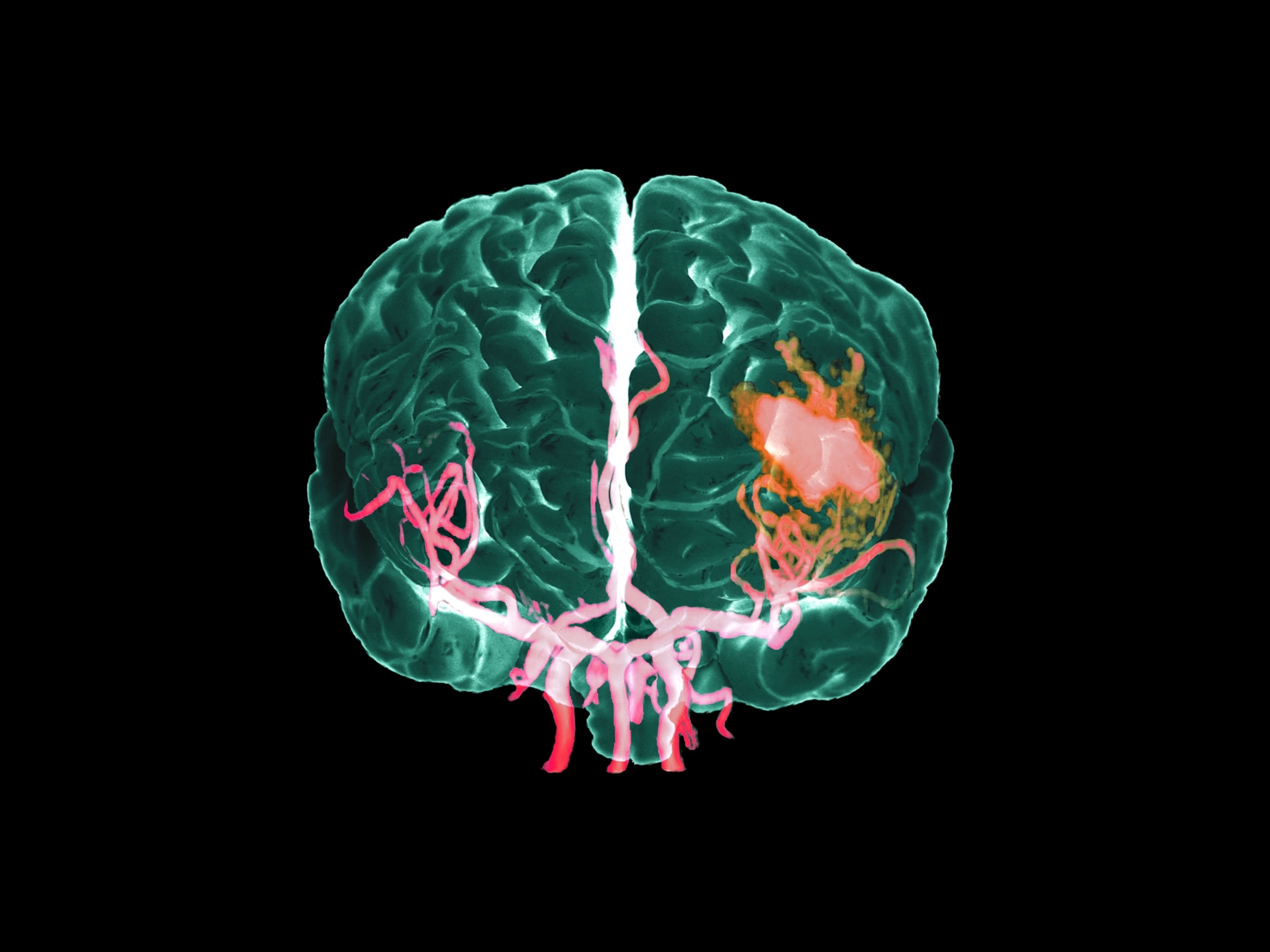

There are also more advanced tools that doctors can use to measure central adiposity, like MRI and DEXA body scans, but these technologies aren’t easily accessible to most people.

Ultimately, all these metrics have some drawbacks, and experts think BMI is unlikely to go away anytime soon, at least not within the next decade.

Tomiyama argues that it might be time to throw our scales away entirely. “If the health is in order then there’s no need to mess around with the weight.” Instead, she suggests focusing on healthy eating and exercise.

Stanford points to the Olympics as an example of how even elite athletes have many different body types. “I like to say it's a tapestry. There’s not one shape and size that equals healthy,” she says.