How La Niña Could Affect the Spread of Zika

With the virus already spreading farther north, the weather pattern's onset could change its distribution.

This year, one of the strongest El Niño events on record affected weather patterns worldwide, bringing with it major flooding and severe drought that impacted the health of millions. El Niño has ended, but scientists are now monitoring for the onset of its counterpart, La Niña, which may create conditions that exacerbate the spread of mosquito-borne diseases like Zika virus.

La Niña is characterized by the cooling of ocean surface waters in the equatorial Pacific and affects many of the same regions as El Niño. Based on previous years, this means above-average rainfall and potential flooding in southern Africa, Southeast Asia, and northern South America, and drier than average conditions in eastern Africa and the west coast of South America. There's a 55 to 60 percent chance La Niña will develop during the upcoming months, according to an August forecast from NOAA.

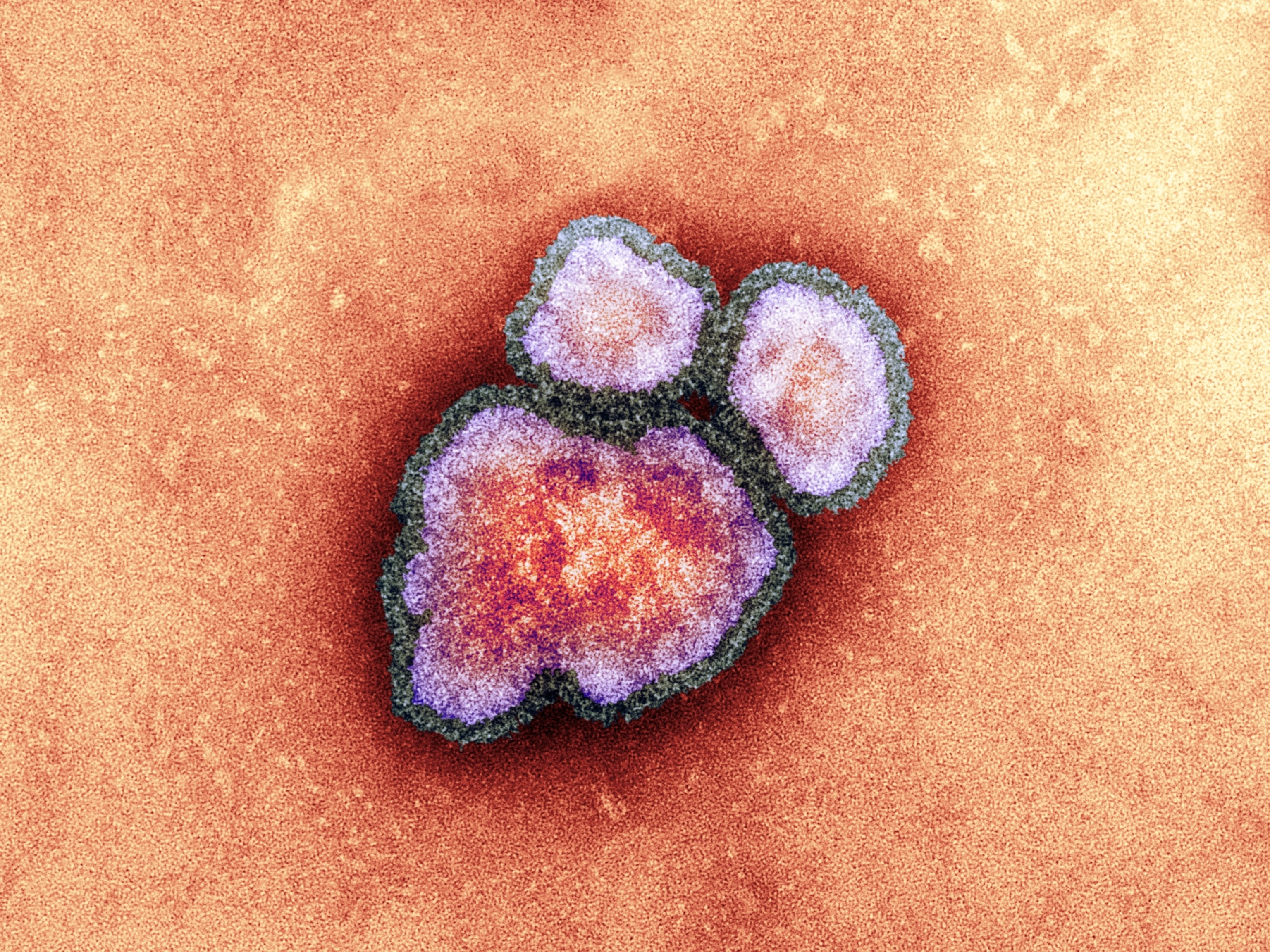

This is a public health concern because certain climatic factors like temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall are strong environmental drivers of vector-borne disease transmission, said Courtney Murdock, assistant professor in the Department of Infectious Diseases at the Odum School of Ecology. This means the abundance and survival of pathogens such as Zika virus may ebb and flow with changes in weather caused by La Niña.

In South America, where the Zika outbreak has been at a peak, the arrival of La Niña would normally signal cooler conditions and hopes for fewer disease-bearing mosquitoes. But other factors may yet play a role in Zika’s prevalence.

“Even if we have a La Niña in the next few months, which tend to be associated with cooler than normal temperatures in northern Brazil and northern South America, we still expect to see warmer than normal temperatures in those regions because of decadal and climate change signals,” said Ángel Muñoz, a climate scientist with the Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Program at Princeton University and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society at Columbia University, in an email.

A recent report from the IRI projected that heavier rainfall associated with La Niña may further increase transmission rates in regions of Latin America and the Caribbean.

The Human Variable

Another concern is that this year's La Niña could change the spread patterns of the mosquitoes that carry the Zika virus, which are already moving farther north.

According to Justin Lessler, associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, "we will likely see a shift in geographical distribution of the virus." Our best proxy for how the risk may change, he says, is probably dengue virus, "because it's also spread by the same mosquito."

Historically, dengue epidemics have been positively correlated with wetter La Niña conditions, according to the World Health Organization. Although this may provide clues about how Zika might behave, transmission is a complex process and can be influenced by a variety of environmental and human variables.

Mosquito traits—like lifespan and rate of reproduction—interact with a pathogen to determine how many mosquitos actually become infectious, how fast the pathogen takes to develop within the mosquito, and how susceptible a population is to infection. Environmental variables, such as temperature, can affect these traits, but scientists haven’t adequately studied Zika virus to make reliable predictions.

Human behavior and sociodemographics such as travel, poverty, human density, and housing structures are other wild cards in the transmission cycle.

“In the [United] States we might have a lot of environmental suitability for transmission, especially on the southern coast, but we’re probably not going to experience outbreaks of the same magnitude that we’re seeing in Brazil and other areas in the Americas because we interact with mosquitos in very different ways,” Murdock said.

For example, while increased rainfall and flooding can increase mosquito-breeding habitats, people may also spend more time inside and therefore be less susceptible, Lessler said.

Conversely, in times of drought people tend to store water. These water containers can concentrate and boost mosquito-human contact, leading to increased rates of infection.

Unfortunately, arboviruses like Zika are notoriously difficult to control, says Murdock. Since we don’t have licensed vaccines for most of them, control methods rely on insecticides and education campaigns on how to minimize breeding habitats.

“Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, which have been implicated in Zika transmission, can breed in a bottle cap,” Murdock said. “Trying to reduce all of the breeding sources is actually really difficult to do, and then we have insecticide resistance.”

Here to Stay?

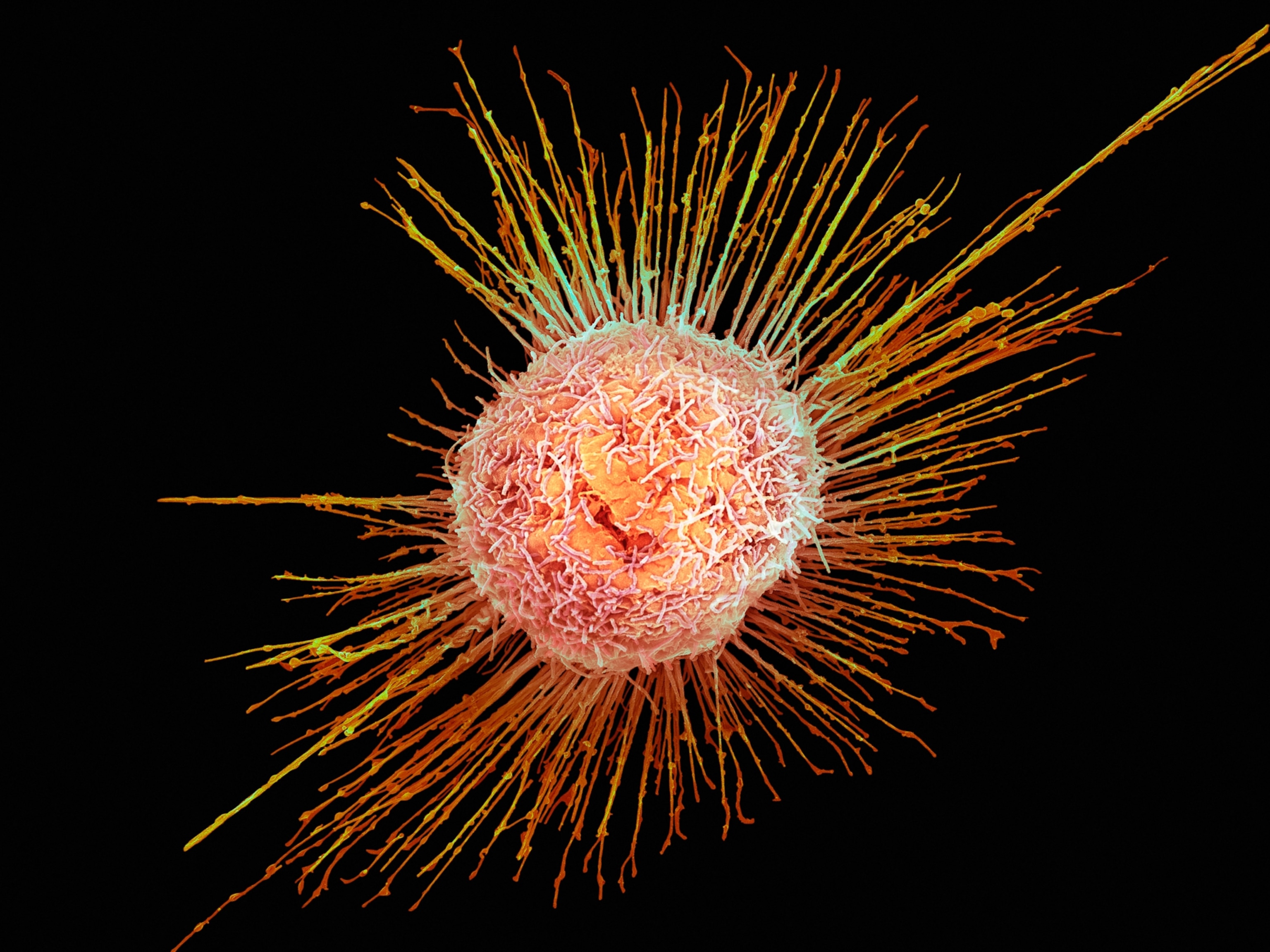

The National Institutes of Health recently announced that it will begin its first human clinical trial of the NIAID Zika virus investigational DNA vaccine, the first step in a multiphase certification process.

Normally the approval process for new drugs or vaccines takes several years, but in emergencies—like for Ebola and now Zika—this process can be accelerated. This may not mean much for stemming the current outbreak, however.

“I suspect that they will not be able to have a licensed vaccine in time for the current wave of Zika in the Americas, because it’s likely to peter in the next two to three years,” Lessler said.

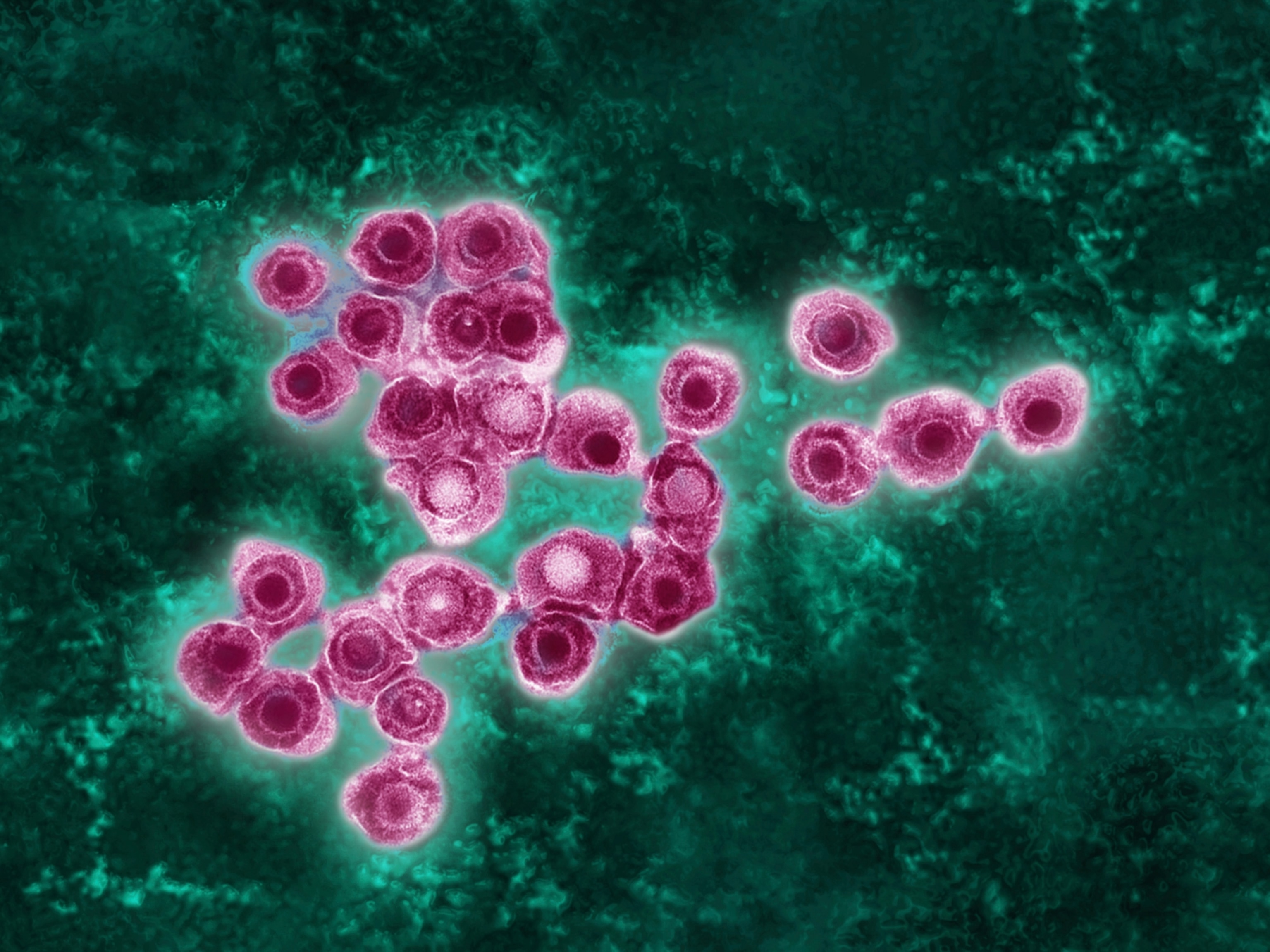

Scientists expect that the initial swell of Zika will build herd immunity. This means when a significant portion of the population develops immunity to the infection, those who are not immune are afforded a certain level of protection. This doesn’t mean Zika will disappear forever, Lessler says. Over time susceptible individuals may build back up, putting the population at risk once again.

“Providing we do get the vaccine licensed, it’s the type of long-term intervention that we should be thinking about for Zika,” Lessler said. “Even if it goes away in the short term, it’s likely to remain with us over decades to come.”