Cape Town, South Africa — It’s a balmy July morning, and a raucous troupe of African penguins is acting out their breeding drama on a sun-toasted Foxy Beach, in False Bay, outside Cape Town: Stage right, a courting pair necks coyly, beaks snipping like a barber’s shears. Nearby, another couple puts the last touches to their shallow nest, adding bits of washed-up kelp that are as dry as beef jerky. Two soon-to-be parents fuss over their egg, while a neighboring chick squawks fiercely for breakfast. Over there is a gangly teenager, as tall as its parents, though its fuzzy blue-gray down is a reminder that this youngster isn’t quite ready to launch into the chilly Atlantic to forage for itself.

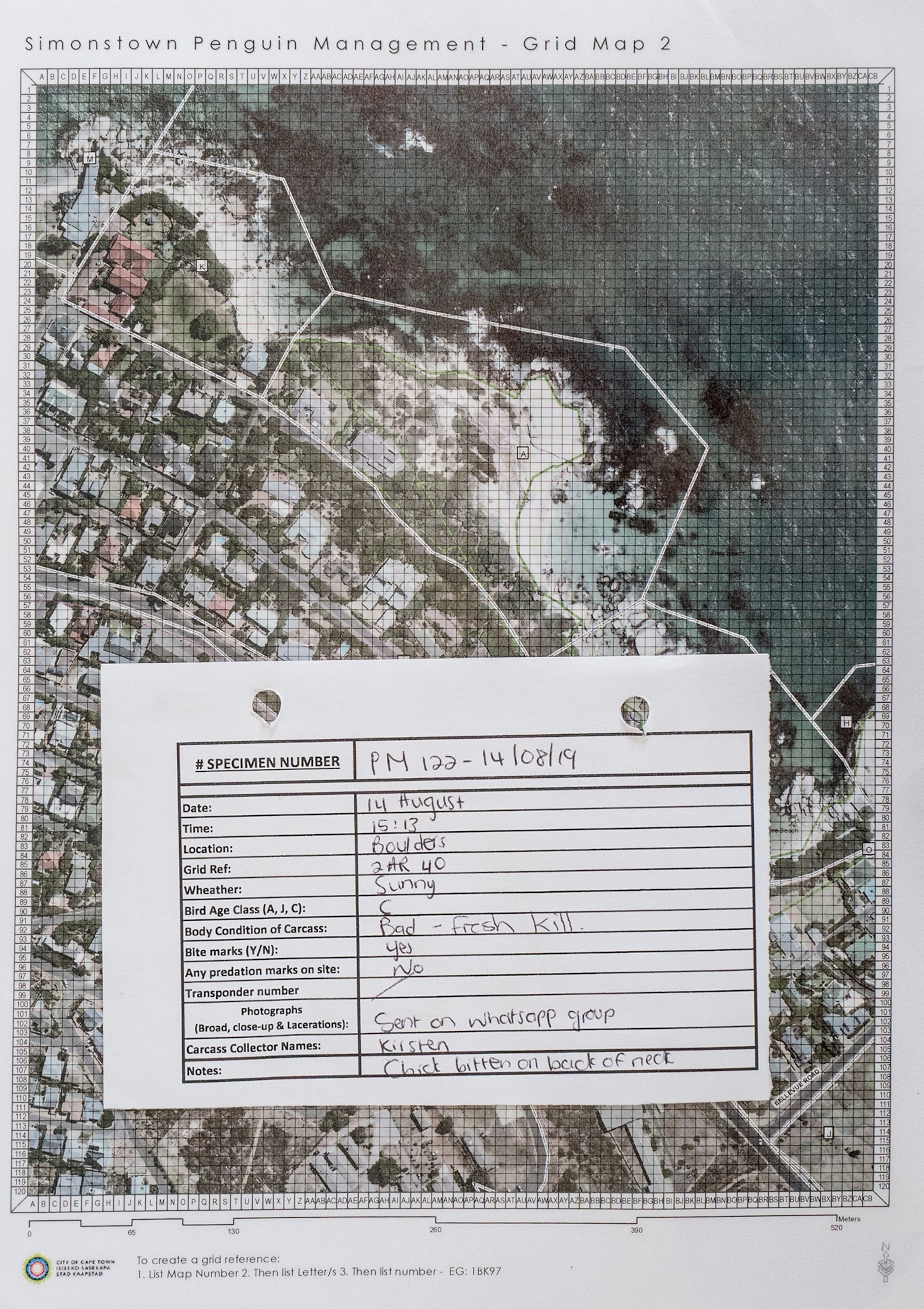

Katrin Ludynia, research manager for the nonprofit Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds, is taking this in from a viewing deck when she notices something amiss. A solitary adult is prone on its belly and oddly still. One leg is extended backward and looks rigid.

Within minutes, a ranger is creeping into the throng, net in hand, to capture the stricken penguin. The bird has fishing twine coiled tightly around leg. “It’s cut through the flesh, basically down to the bone,” Ludynia says after inspecting the inflamed wound.

The injury is serious enough to need veterinary treatment, so the animal is driven across town to the foundation’s rehabilitation center to join dozens of other penguins—chicks hatched from rescued eggs, abandoned youngsters, or injured adults—for hand-rearing or rehabilitation. “Hopefully once they have cut the twine out, they’ll be able to close the wound. If not, they may be able to amputate,” Ludynia says. “Some birds can survive with a stump.” If the penguin recovers, it may be released back into the Foxy Beach colony.

African penguins are endangered, which explains why conservationists go to extreme lengths to save individual birds—to bolster the species’ dwindling gene pool. In three decades, penguin numbers in South Africa’s waters have crashed by 73 percent, down from about 42,500 breeding pairs in 1991 to 10,400 by 2021. If this rate of decline continues, the only penguin endemic to the continent could be extinct in the wild within 15 years. Loss of food is the main reason they’re doing so badly, mostly the result of overfishing and also because air and ocean temperature changes are affecting the availability of sardines. (Learn about why penguins in Antarctica are in trouble too.)

Historically, African penguins thrived offshore at islands extending from Hollams Bird Island off Namibia, around the tip of the continent, and along the coast to Algoa Bay.

The mainland-based rookeries at Foxy Beach and at nearby Boulders Beach—a quarter mile away, and a major tourist draw—are bucking the trend, staying stable. They’re part of the bigger Simon’s Town colony that stretches along a mile and a quarter of protected coastline. This population has held steady at about a thousand breeding pairs during the past five years.

At the recommendation of conservationists, South Africa’s environment minister, Barbara Creecy, is considering closing off purse-seine fishing in an approximate 12-mile buffer around the country’s six main island colonies, where 88 percent of South Africa’s penguins live: Dassen Island, Robben Island, Stony Point, Dyer Island, St. Croix Island, and Bird Island.

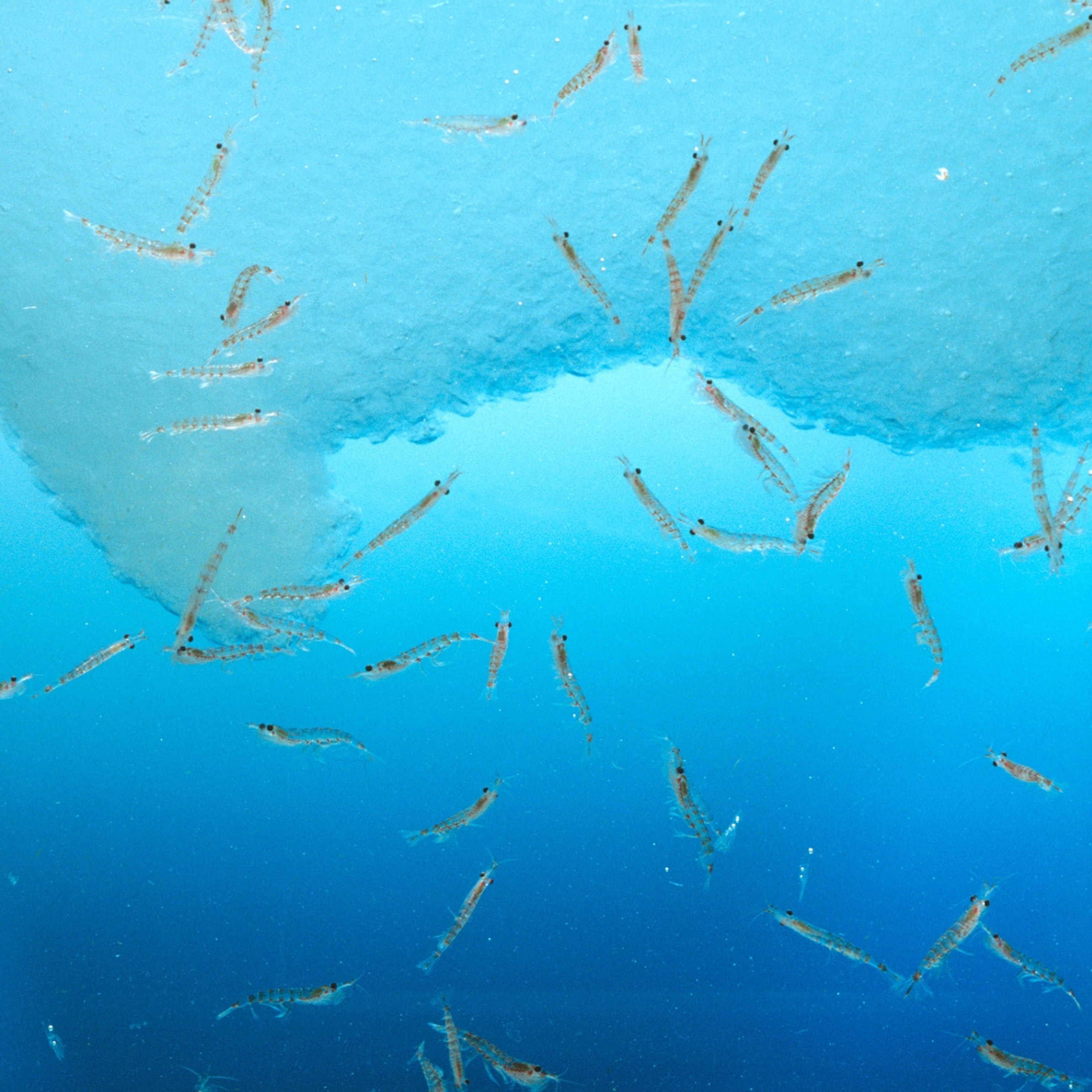

Purse-seining involves scooping a shoal of fish out of the water with a giant hooped curtain of netting. Fishing for small pelagic fish—mostly sardines and anchovies—is an important livelihood for some South Africans. But these are fish the penguins depend on too.

In the past, penguin population management efforts were site-specific, such as monitoring rookeries and recovering stricken eggs and chicks, or injured adults. If the 12-mile buffer plan is adopted, it would be the first time the health of the wider ecosystem is taken into consideration for penguin management. Sardines migrate great distances along the coastline, but should shoals move into the no-fishing buffers, foraging penguin parents would have dibs on the food needed for their chicks.

Precision-engineered torpedoes

On land, African penguins are a Hallmark caricature, tottering along and braying like donkeys, earning them the nickname “jackass” penguins. But once they slip into the sea on the hunt for sardines and anchovies, they’re precision-engineered torpedoes, powering through the water with flipper-wings, tweaking their webbed feet to steer them toward increasingly hard-to-find prey. (Read about what makes penguins smart.)

Sardine stocks have collapsed. In 2019, the fisheries ministry closed commercial sardine fishing for a season, and last year the fishery was still regarded as depleted.

Penguins are also struggling to find enough food because of changing marine conditions. Global warming is altering wind patterns and ocean current upwellings, causing fish to spawn in different areas, and the penguins don’t seem to be finding them as before. Recent satellite tracker monitoring of penguins’ foraging expeditions shows birds still following specific environmental cues that have taken them to waters along the western coast of southern Africa, which are no longer abundant with fish.

In August, rangers with SANParks, South Africa’s parks management authority, and the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds rescued nearly a hundred starving chicks from Bird Island—one of the easternmost colonies in Algoa Bay, some 450 miles from the Simon’s Town colony—and took them to a nearby rehabilitation facility for hand-rearing. (Go inside an African penguin rehab center in this 360-degree video.)

The Algoa population has fallen by about a third during the past two years alone, according to the 2021 census. If such drastic declines were to occur regionally, the African penguin would qualify for “critically endangered” listing by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, according to a report by a collaboration of government, nonprofit, and university marine scientists.

Conservationists at SANParks and the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds say recent rescues of starving Cape gannet and Cape cormorant chicks in Algoa Bay are further harbingers of the threat of a wider ecosystem collapse as sardine stocks continue to plummet.

Degraded nesting habitat partly explains the decline of the offshore populations. African penguins prefer burrowing into bird droppings, called guano, that accumulated up to 32 feet deep on the islands over centuries. Well insulated against the elements, guano provided a safe nesting place, but after the natural fertilizer boom began in the mid-1800s, most islands have been stripped bare of their “white gold.”

Penguins also face disturbances such as shipping traffic through their foraging grounds, human traffic at nesting sites, avian flu and other diseases, oil spills, and predation by seals and sharks.

A penguin colony apart

Penguins established the Simon’s Town colony relatively recently. In 1985, a few breeding pairs arrived and dug their nests in the sand and under nearby shrubs, and since then the population has grown and stabilized. False Bay is closed to commercial pelagic net fishing, so these birds don’t have to compete with the industry for sardines and anchovies.

The Simon’s Town colony is also unusual for being close to city life. The nesting sites are easily accessible to visitors, along boardwalks or directly on beaches, making them among the few places where people can observe the penguins close at hand.

Ludynia isn’t too worried about the effects of human curiosity on this population’s stability. The penguins are habituated to people, and, she says, the more confident ones even choose to nest in gardens and close to boardwalks. “The birds at Simon’s Town are pretty used to people,” she says. “We know from other colonies that shier birds, or birds easily disturbed, will move to areas with less disturbance. Seeing that Simon’s Town has a large variety of habitats, I think birds choose the right space for themselves.”

Some beaches have high tourism traffic, particularly during the sensitive molting season, which coincides with the summer beach-going peak. While most tourists keep a respectful distance from the birds, SANParks marine biologist Alison Kock says that selfie-seeking visitors sometimes do get closer to penguins than the recommended 10-foot distance. “Some people don't respect that and try to get too close or touch the birds,” she says. “We ask that if the bird shows any signs of being uncomfortable, that people move back.”

Such disturbances are minor, though. Even a recent freak incident this September, when bee stings killed 63 penguins, isn’t “going to have an impact on the overall population level the way that other key threats are, particularly the reduced food availability, which is where most effort needs to be focused,” says Laurent Waller, an ecologist with the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds.

With climate change expected to bring more extreme weather events, storm surges or severe heat could drive the most dedicated coastal penguin parents from their nests. The shallow beach nests are exposed to the sun and heat, storm waves, and scavengers such as seagulls.

In the autumn of 2002, for example, a spring tide coincided with an intense storm whose surge devastated the Foxy Beach rookery. A researcher from the University of Cape Town’s Avian Demography Unit who visited the beach the next day found many nests flooded, with eggs washed out by the tide, and the bodies of chicks that had succumbed to hypothermia or drowned.

Experiments to create more durable artificial nests are under way, aimed at improving the Simon’s Town colony’s breeding success. And conservationists are releasing rehabilitated birds at De Hoop Nature Reserve, a marine protected area on the south coast near Cape Agulhas, hoping to establish a new colony there.

Meanwhile, David Roberts, a veterinarian with the seabird conservation foundation, was able to remove the twine from the leg of the penguin from Foxy Beach. It had cut close to the bone, Roberts says, and if the wound had been a few days older, they’d have had to euthanize the bird—an amputation that high on the leg would make it unlikely that the penguin could survive in the wild.

A week later, the penguin could be seen waddling from a rehabilitation pen toward a swimming pool to spend an hour or so splashing about with others of its kind—daily exercise to keep their limbs strong and their feathers waterproofed ahead of a possible return to Foxy Beach come spring.

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Explorer Mélanie Wenger’s work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.