A Rare Look at the Disappearing World of Antarctica's Whales

As the southern continent rapidly warms, some whale populations are booming—while others are suffering from lack of ice.

Cierva Cove, Antarctica — Ari Friedlaender kneels at the front of our inflatable boat as it bobs on the ocean.

He holds a rifle, with two metal harpoons protruding from its muzzle. His gaze is fixed a few feet ahead, where something big stirs just beneath the surface. “OK, put it in neutral,” he says to the driver. Our boat drifts closer.

A jet of mist suddenly erupts from the water. The humpback whale exhales with a grunt, emitting a putrid whiff of stomach acid and decay.

The Oregon State University marine ecologist brings the rifle to his shoulder and pulls the trigger. The dart flies into the animal's dorsal fin just as it sinks beneath the waves.

It’s a perfect shot: The small GPS sensor will stay lodged in the whale’s fin for a month. Each time the giant surfaces, its sensor will transmit the location to satellites.

Friedlaender, also a National Geographic explorer, is plying these waters to study the private lives of Antarctica's two most common whale species, the humpback and the Antarctic minke.

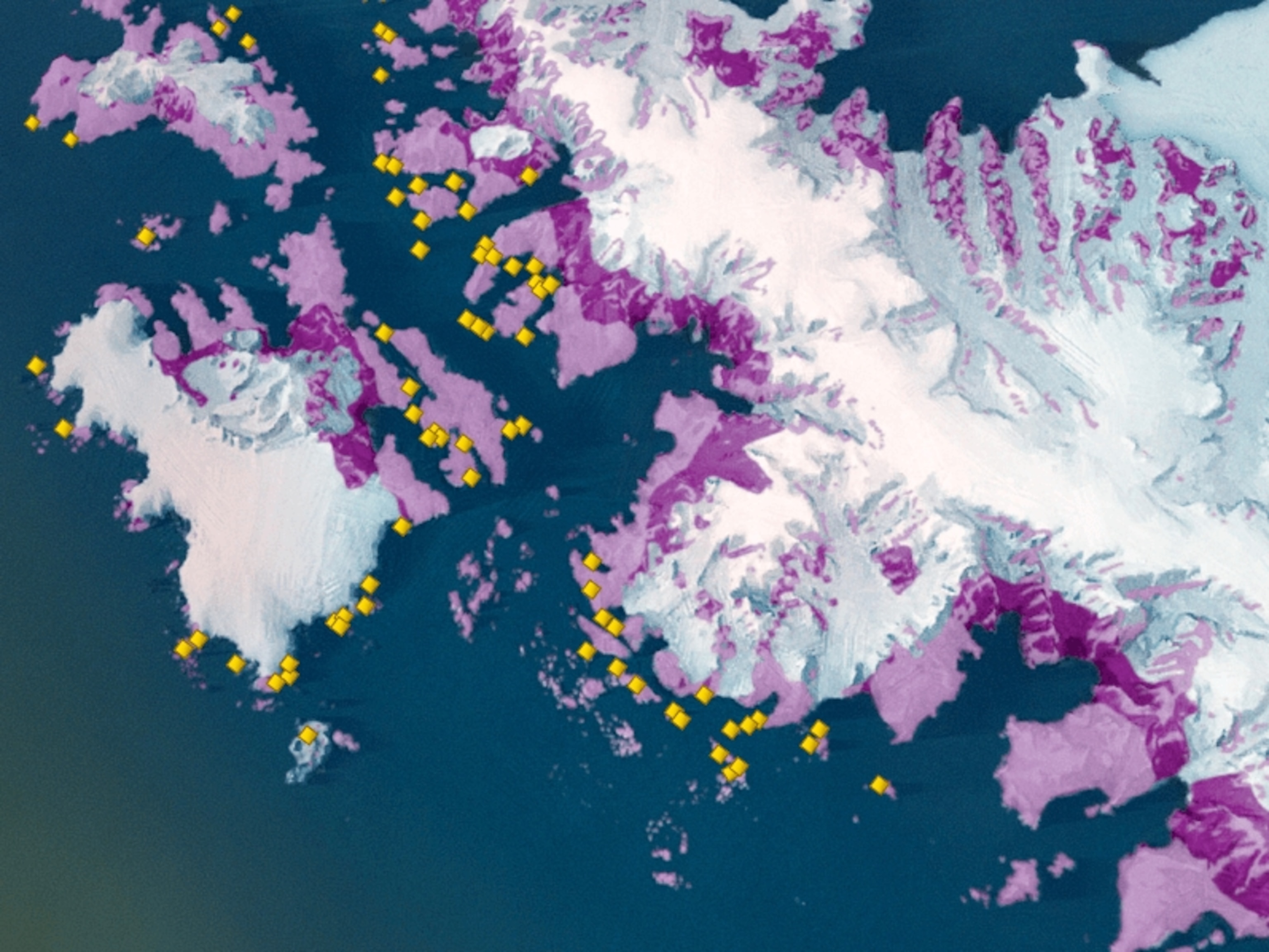

He's focused his efforts on the northwestern edge of the Antarctic Peninsula, where Cierva Cove sits. This region is one of the world’s key feeding grounds for these animals. It is also—thanks to humans—one of the fastest warming places on Earth. (See beautiful drone video of migrating humpbacks.)

Average annual temperatures on the western side of the Peninsula have warmed by 4 or 5 degrees Fahrenheit since 1950, and the winters have warmed an astonishing 8 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit—“over five times faster than the global average,” according to Douglas Martinson, an oceanographer at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York.

Sea ice has also shrunk: Since 1980, the average duration of winter sea ice has shortened from around seven months to just four.

On one hand, the melting has given humpback whales, which prefer open water, more room to find food. But it may spell disaster for the Antarctic minke, a species that depends on ice for its survival.

The loss of sea ice “has really changed the abundance of animals,” Friedlaender says.

“There are way fewer minke whales in this area than you would expect, and enormous numbers of humpback whales. It’s almost staggering.”

Peering Under the Ice

It's well known that humpback whales are multiplying in the waters around Antarctica as they recover from decades of whaling that finally ended around 1970,when Soviet factory ships ended their illegal harvests.

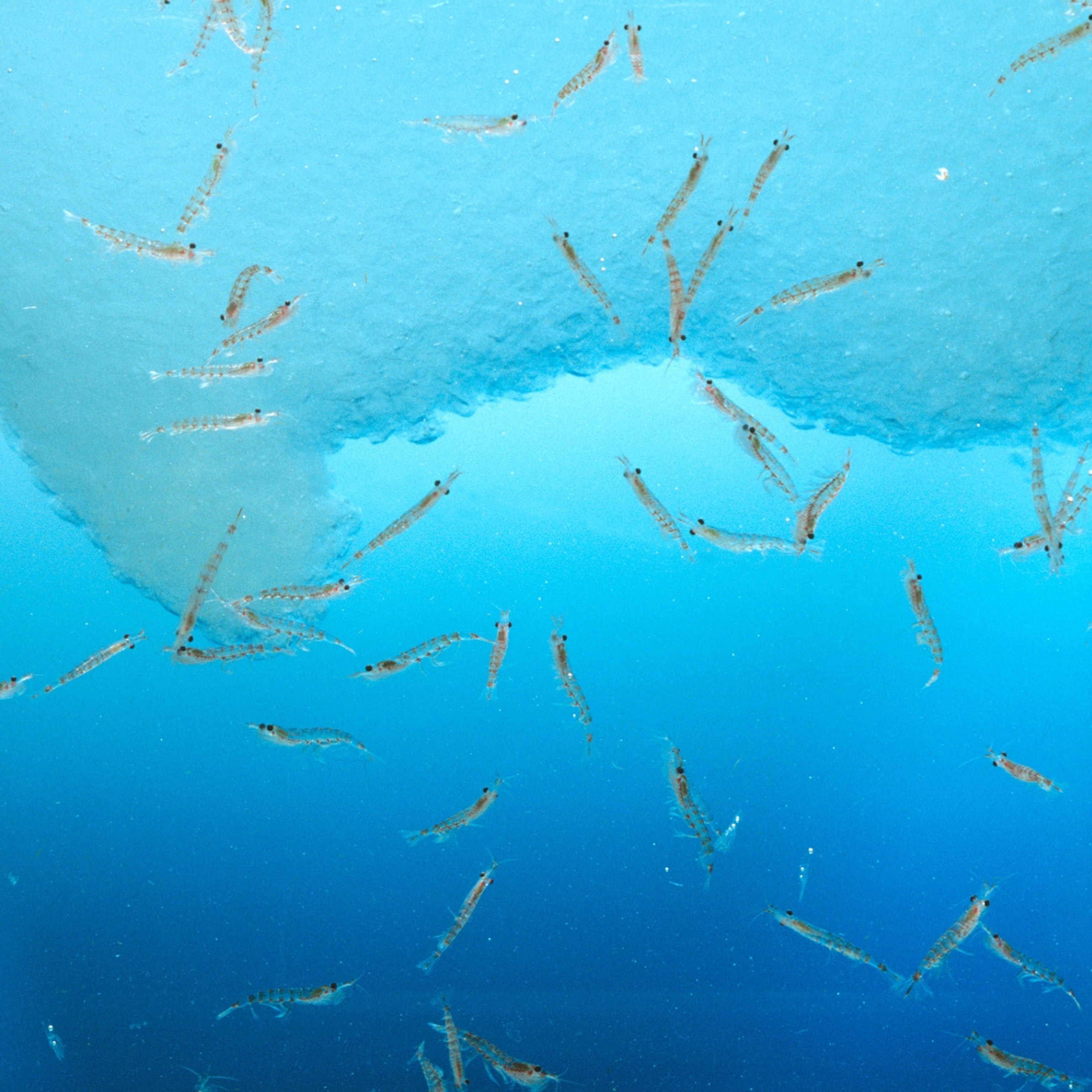

In 2009 Friedlaender witnessed the largest gathering of humpback whales ever documented. Over 300 whales congregated in a single bay to feed on krill—an estimated two million tons of these tiny whiskered crustaceans.

But less is known about why Antarctic minke are declining—there isn't even enough information about them to determine their conservation status, how quickly their numbers are falling, or whether they are simply retreating into smaller areas of ocean.

What Friedlaender knows is this: In the early 2000s, minke accounted for up to 40 percent of the whales that he saw along the Antarctic Peninsula. Now they account for only about 5 percent. It doesn't help that they're skittish and hard to study. During our cruise in March, we rarely saw a minke for more than a few seconds.

To find out why these populations are changing, Friedlaender spent the entire Antarctic summer sticking sensors on minke and humpbacks. Some, like the one he just deployed with an air rifle, track whales' movements for weeks.

Another type of sensor, a suction cup stuck gently on a whale's back using a long pole, collects more detailed information. For 24 hours, the sensors record the animal’s second-by-second choreography as it dives below the surface—capturing every corkscrew twirl and every feeding lunge as the animal engulfs seawater buzzling with krill.

In 2013, Friedlaender managed to put suction cup sensors on two minke—a touchy procedure, and the first time anyone had managed to record this kind of information from these whales.

Safe Haven for Minke

His results, published in 2014, revealed some key insights. Unlike humpbacks, which feed in ice-free water, minke prefer being deep inside fjords, which are strewn with various frozen formations—icebergs plunging hundreds of feet below the surface, or swaths of sea ice forming a blue translucent roof over the water.

For instance, one minke that Friedlaender tracked frequently dove under the sea ice, staying under for as long as eight minutes. It spent most of that time skimming just a few feet beneath, gulping down krill.

Friedlaender and colleagues believe there's a why reason 25-foot-long minke—which are half the size of humpbacks—stick near the sea ice: It protects them from being eating by orcas, a hazard that humpbacks generally needn’t fear.

The team also believe minke are adapted to ice: The animal’s small, maneuverable body and mouth are optimized for flitting around under the ice, gulping down small groups of krill. This gives the smaller whales an entire food source that bigger whales can't get to.

But that advantage is now becoming a liability as sea ice disappears, says Friedlaender. “The available habitat for them is disappearing.”

It is even possible that as their hunting grounds recede, the animals are finding less to eat. Over the last 28 years, the average amount of body fat carried by Antarctic minke has declined by 9 percent, and the average amount of food in their stomachs has fallen 31 percent, according to data collected by Japanese whalers. (Read about 200 pregnant minke whales killed by Japanese whalers.)

Whether these changes stem from the loss of sea ice and difficulty hunting remains to be seen. But scientists have observed a similar pattern among some penguin species: As sea ice retreats from the northwestern Antarctic Peninsula, entire breeding colonies of Adélie penguins, which depend on that ice, have vanished.

Disappearing Prey

Late in the afternoon on Cierva Cove, our boat approached another humpback. As it dived underwater, clouds of reddish brown material suddenly billowed up to the surface—whale poop, infused with the red pigment of digested krill.

Though they're booming now, the humpbacks' gains may be short-lived. Krill also depend on sea ice to reproduce—their offspring spend the winter sheltered under it, eating algae and other organisms from its underside. (See up-close video of humpbacks feeding.)

As warming continues to erase sea ice from Antarctuca, krill may also begin to plummet—cutting off a crucial food source for not only humpbacks but the Antarctic food chain as a whole, Friedlaender says.

By warming the planet, “we’re seeing an experiment that we didn’t intend to do,” says Friedlaender.

“Now we’re seeing the results.”

Douglas Fox is a freelance science and environmental journalist.

Carolyn Van Houten is a photojournalist at the San Antonio Express-News. She was the recipient of the 2016 National Geographic Photography Internship.