Civil War Envelopes Are Works of Art—And Propaganda

Envelopes were relatively new for American mail in the 1860s, and printers used them to take sides.

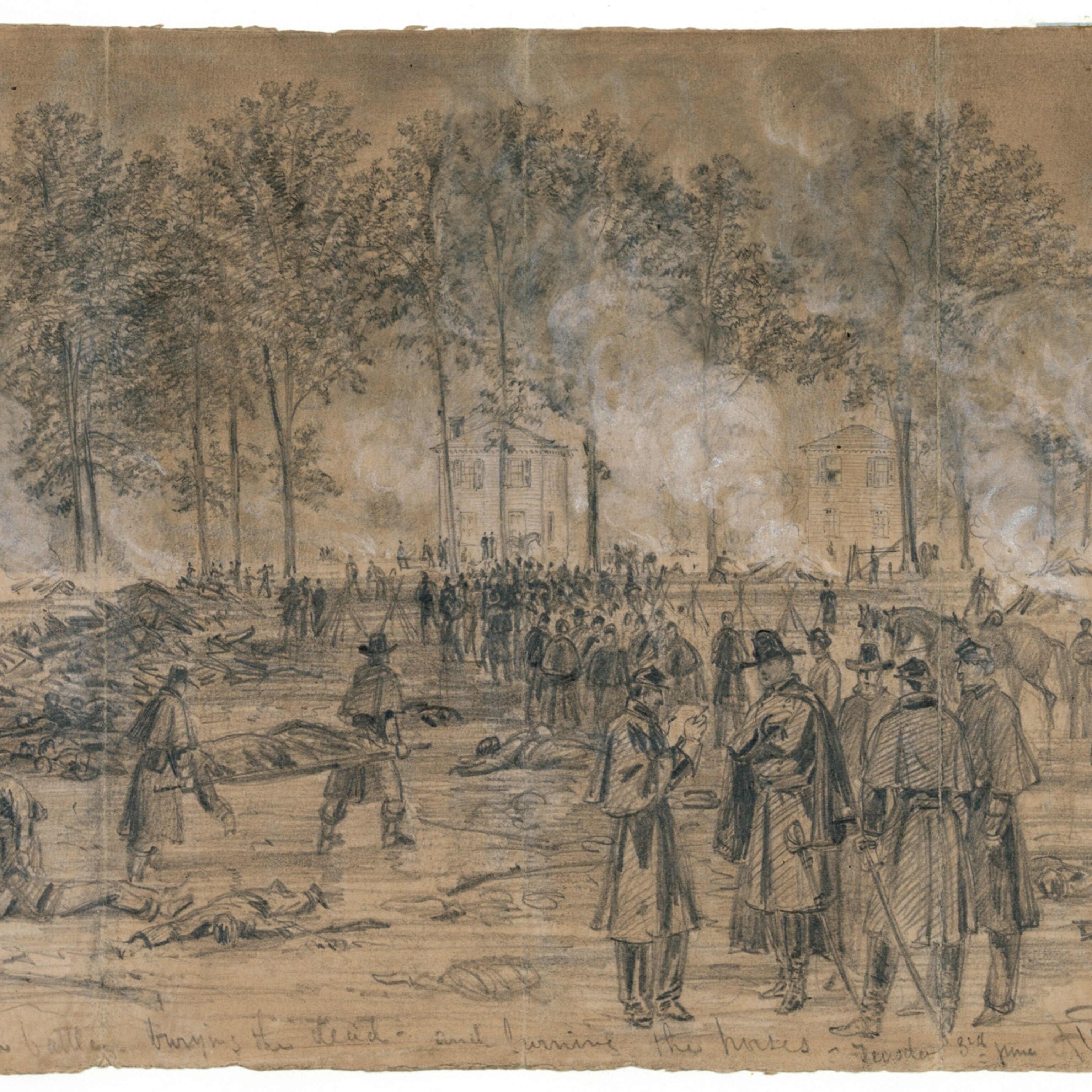

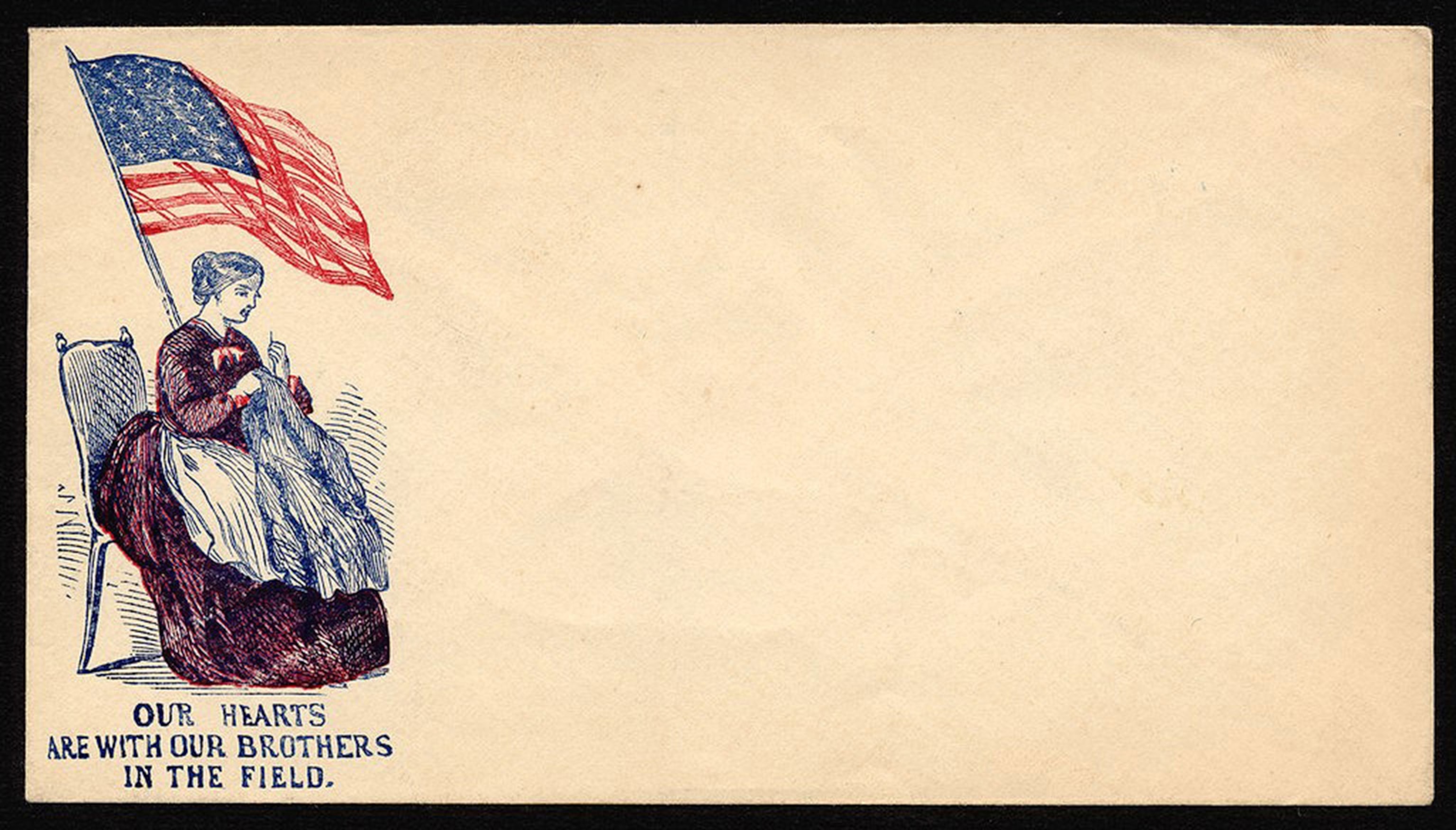

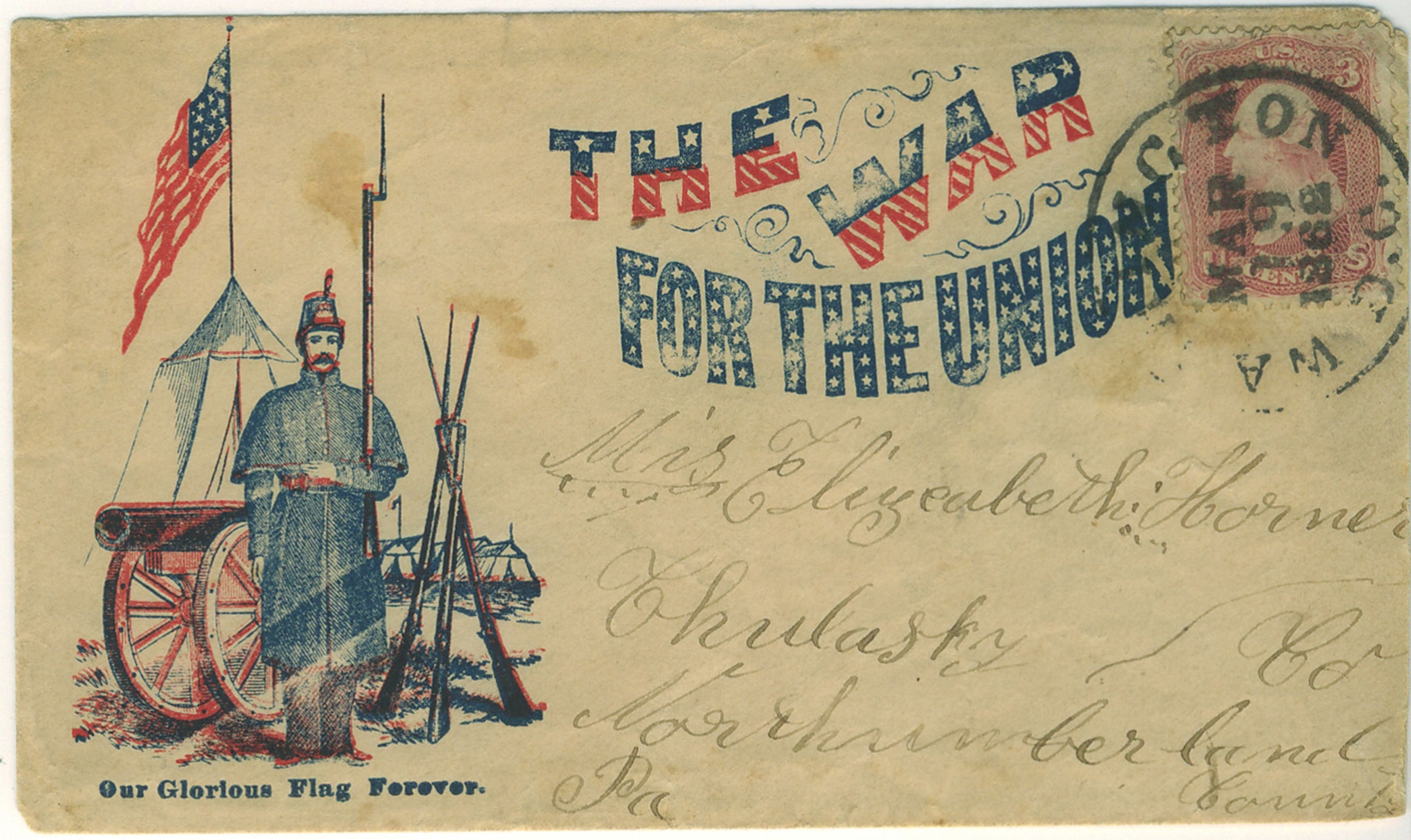

In 1861 and the years that followed, many American men found themselves far from home. Farmhands from rural New York walked the streets of Washington, D.C., serving in the Union Army of the Potomac. Boys from Maine fought in the forests of Virginia. More than 2.6 million men joined the Union Army over the course of the war, while roughly a million joined the Confederate forces. The volume of mail ticked upward with letters to distant homes, and when it was time to send a letter, soldiers and civilians alike reached for a new kind of envelope, freshly printed and decorated with red and blue flags, delicate engravings of eagles, poems about the girl left behind, or the faces of generals, whom people at home might never have seen.

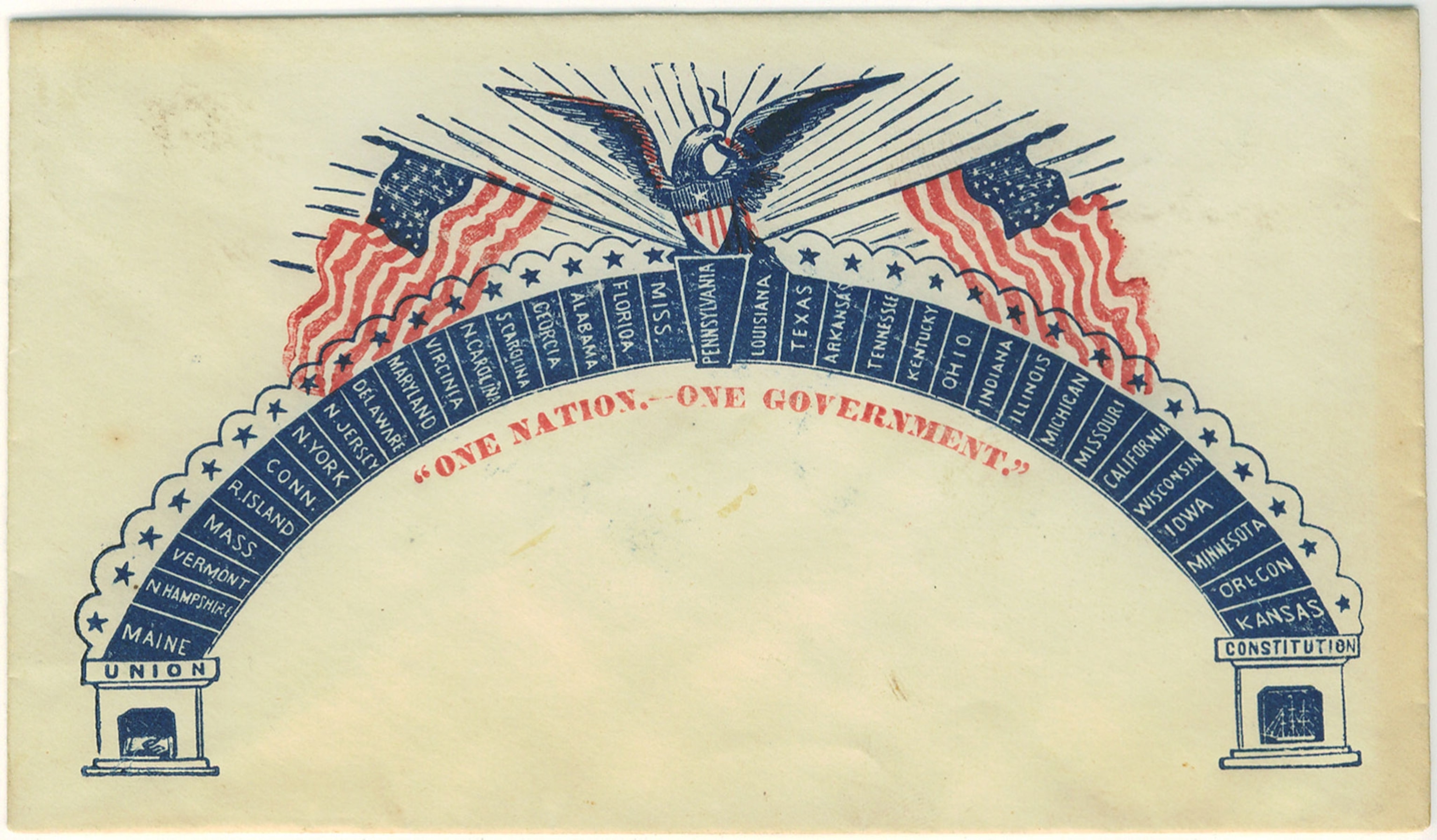

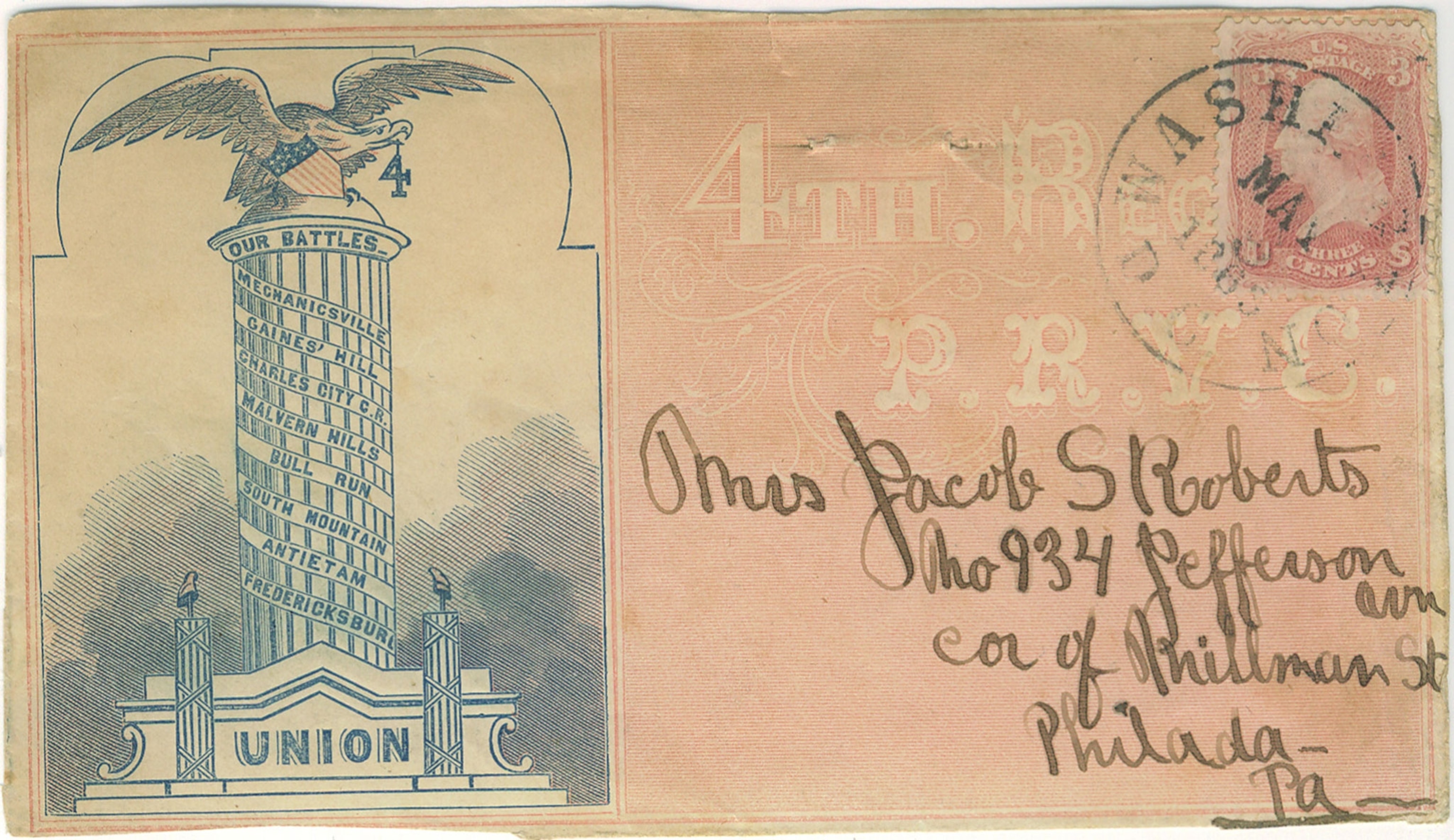

There were many such envelopes to choose from: Over the course of the war, 10,000 or more Union designs were printed, says Steven Boyd, a historian at University of Texas, San Antonio. “You could buy a hundred different designs in a single packet for one dollar,” he says.

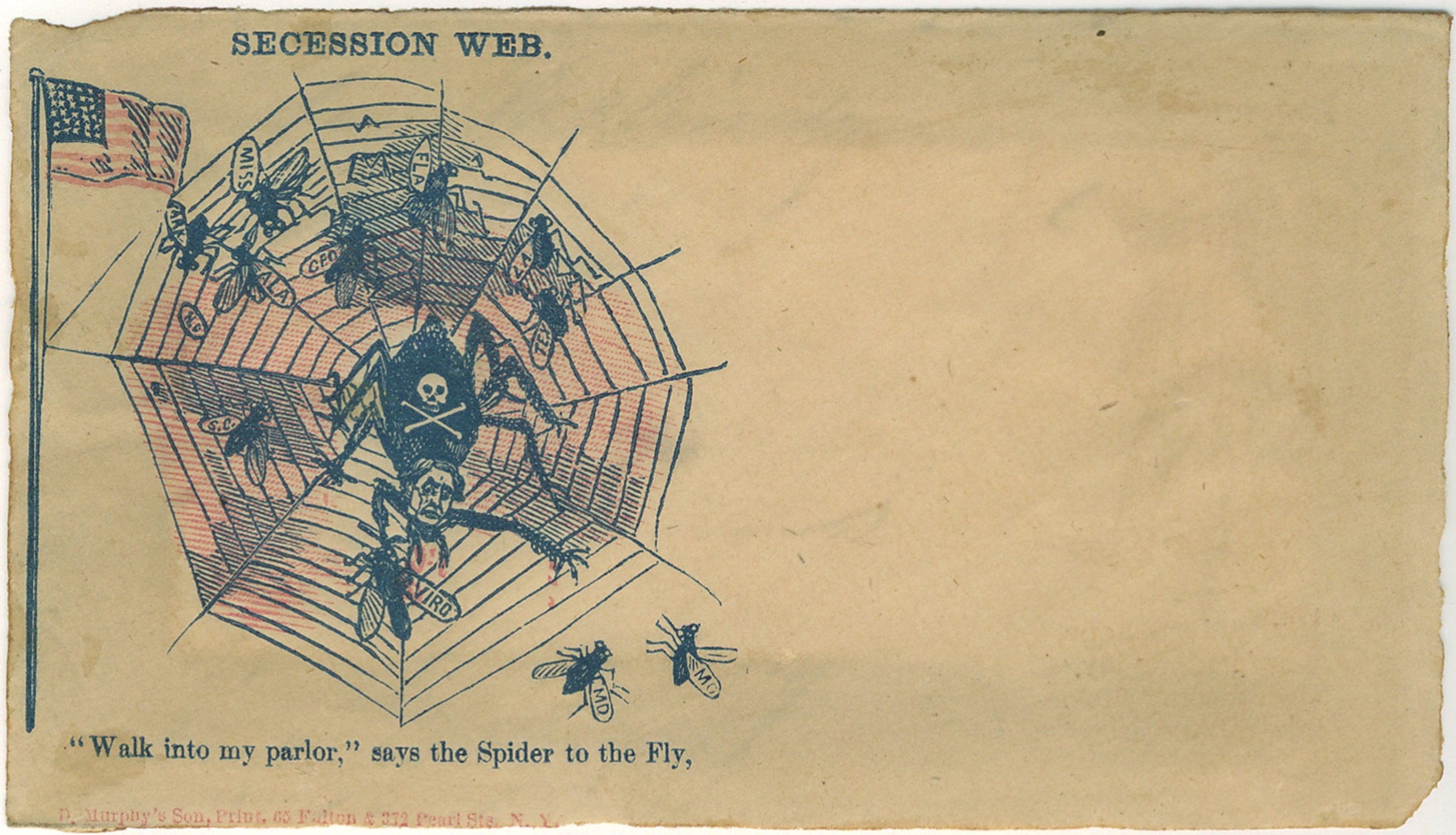

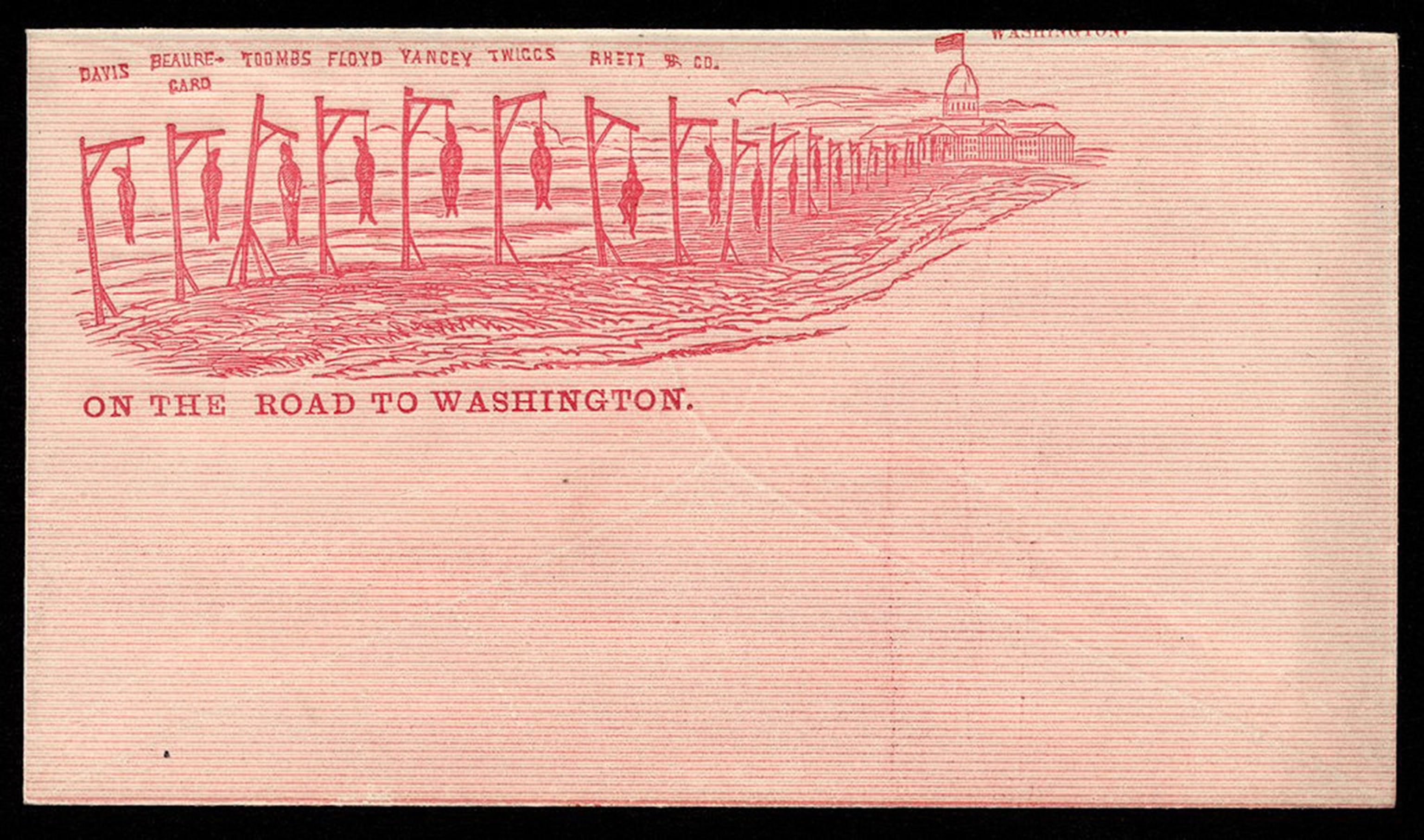

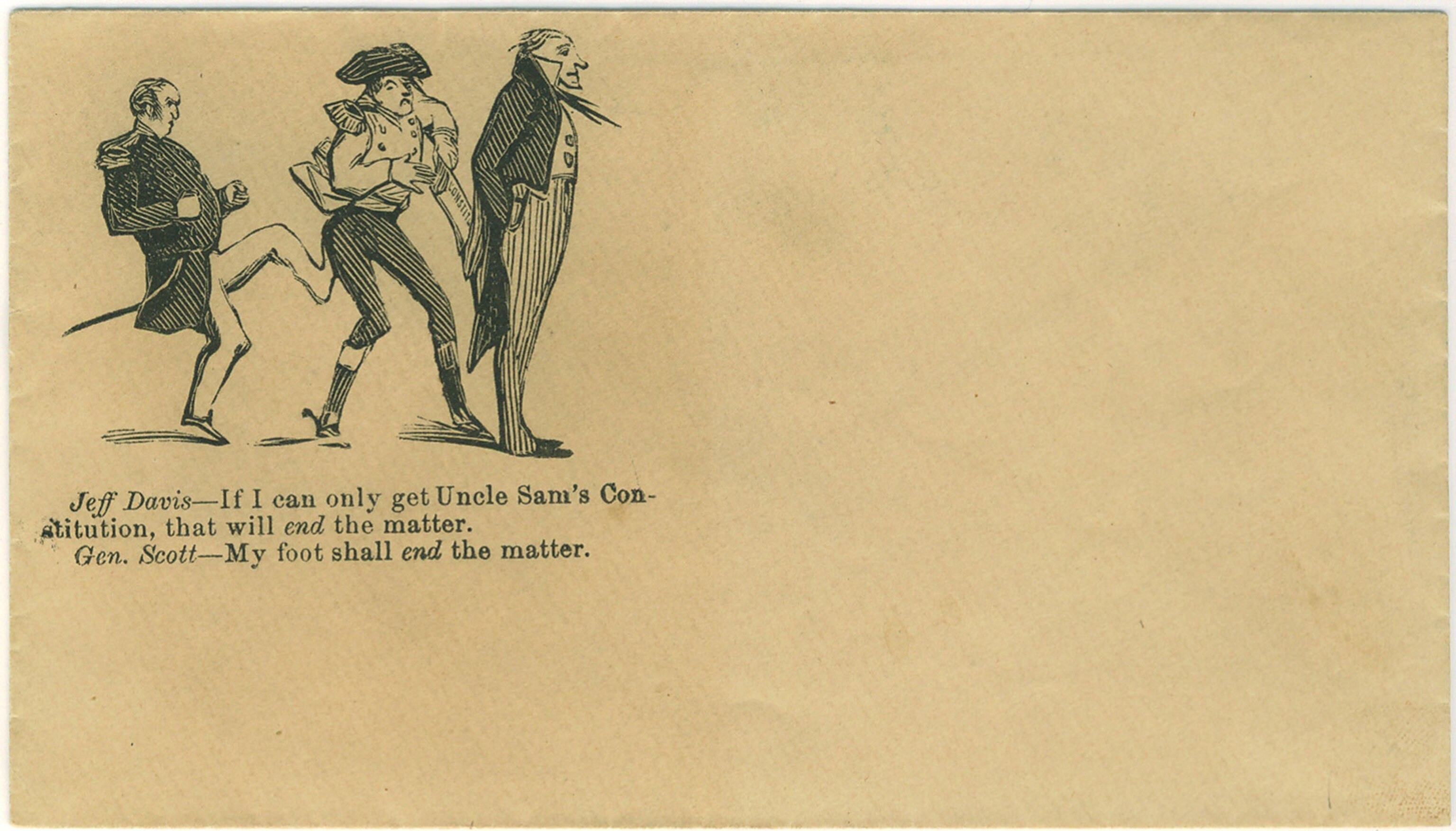

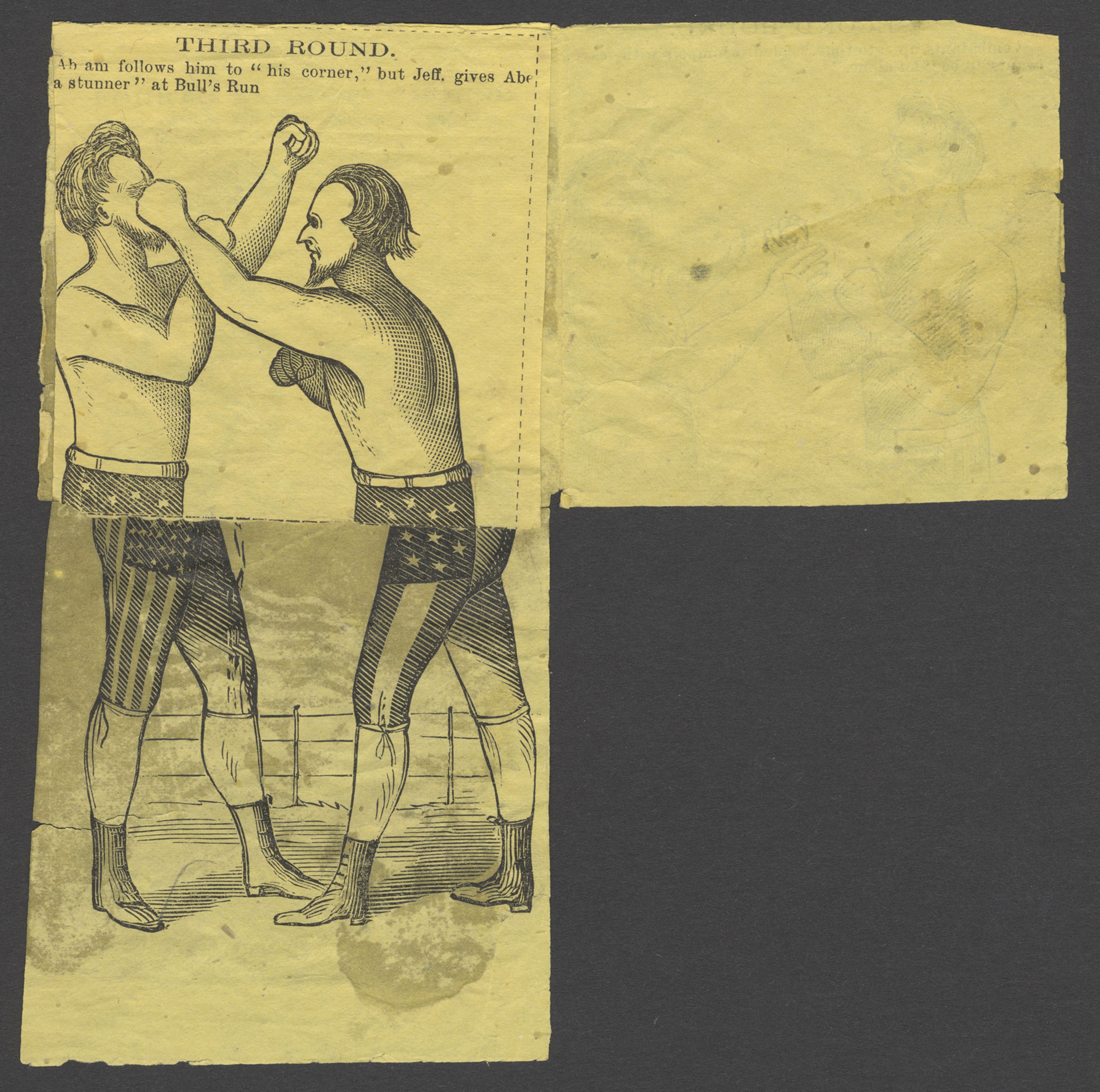

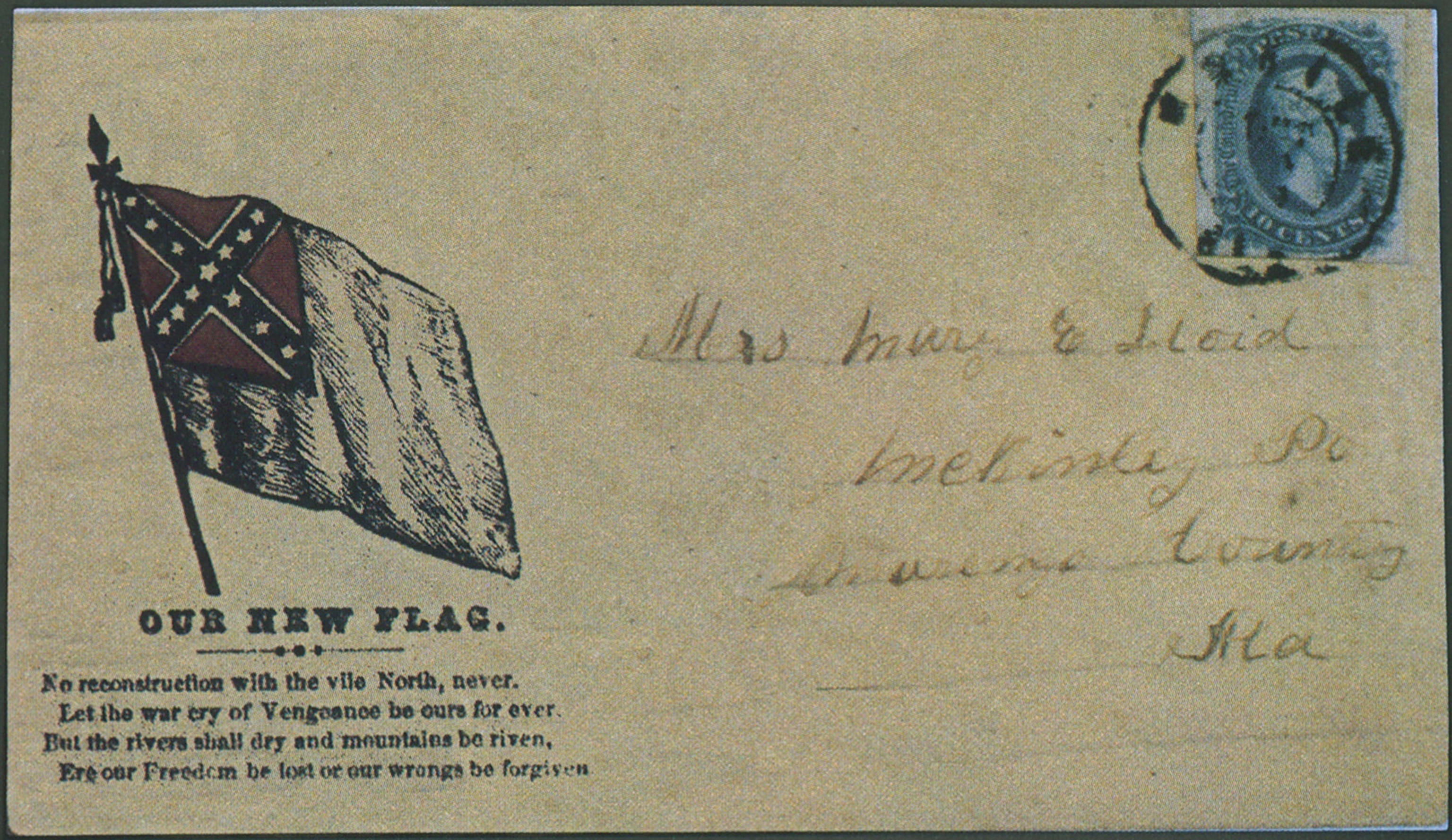

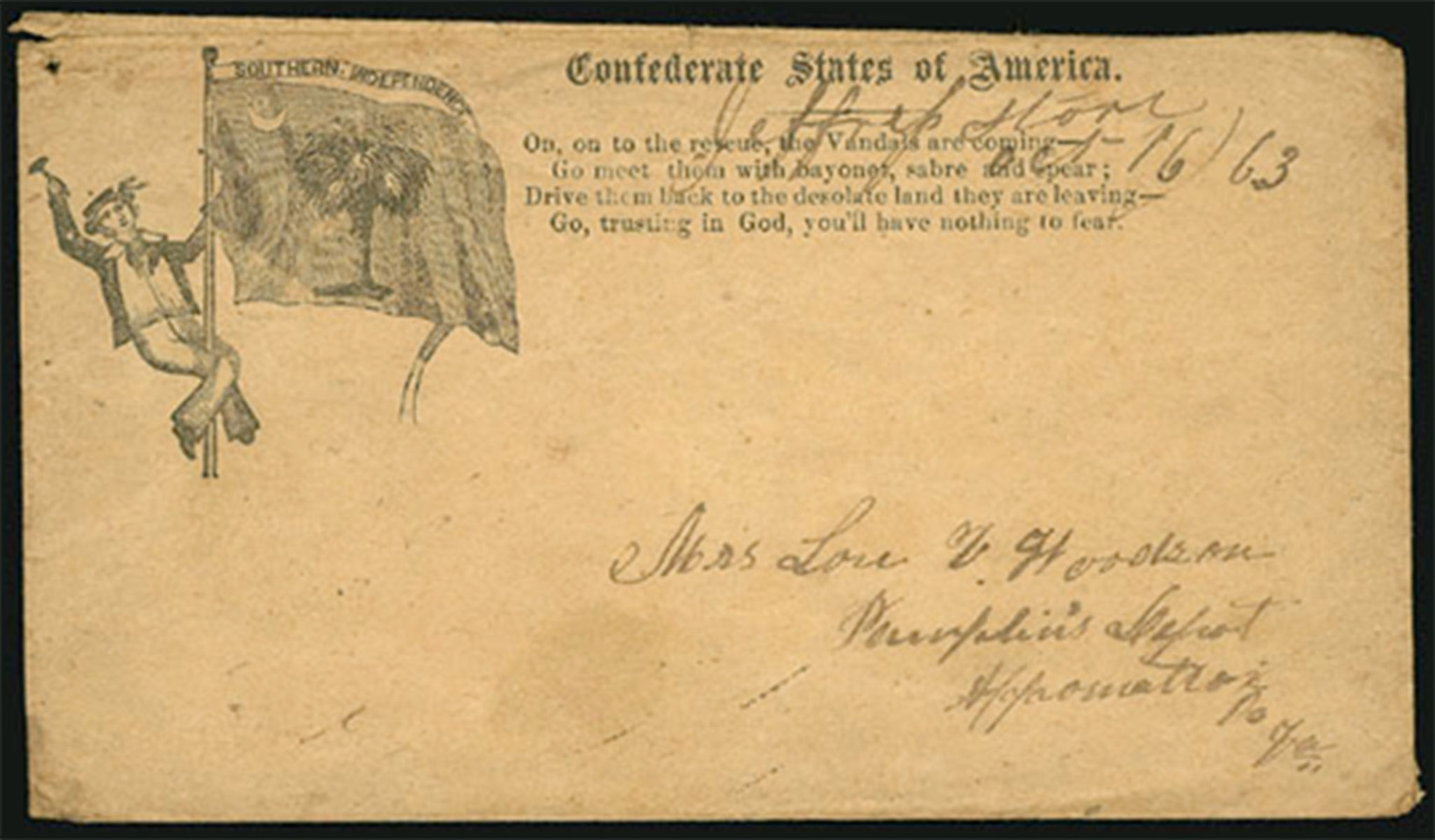

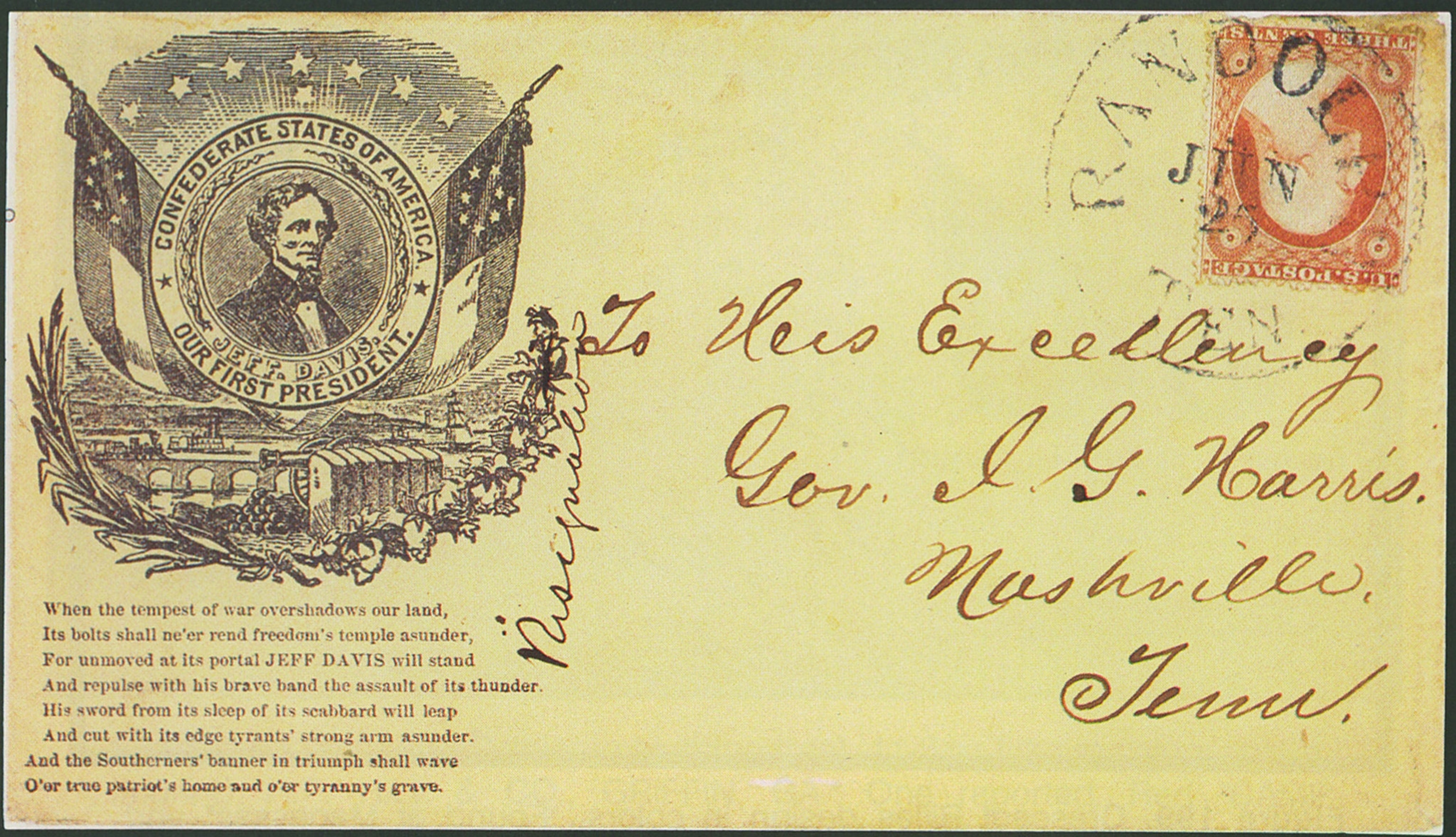

These patterns range from simple flags and mottos to macabre revenge fantasies, with the hanged bodies of Southern generals lining the road to Washington. For a brief period at the beginning of the war, envelopes were printed in the Confederacy as well, and Southerners could send letters with a portrait of Jefferson Davis, “Our First President,” or any number of depictions of the new nation's flag.

This riot of creativity was sparked by, of all things, a change in postal rates. When we drop a letter in the mail now, we don't think of the envelope as a luxury. But until the mid-19th century, U.S. postage was charged by the sheet, so people simply folded their letter and used sealing wax to close it. Reforms to make letters cheaper, however, meant that by 1851, there was a flat 3-cent rate for mail under a half-ounce and traveling less than 3,000 miles. Envelopes, made on newly invented envelope-folding machines, flew out of stationery stores.

The potential for using envelopes as advertising must have been clear early. During the presidential campaign of 1860, Americans could use paper and envelopes featuring their favorite candidates. When war broke out the next year, printers were quick to see the benefits of reusing some of their old designs. Add a couple of Union flags and a motto to a campaign portrait of Abraham Lincoln, as Boston printer James Whittemore did, and you had a new product. Add “True to the Union and the Constitution to the Last” under a picture of Stephen Douglas, who ran against Lincoln and died shortly after, and you might sell a few to his supporters.

Printing patriotic envelopes was a profitable business in the North, Boyd says. There were printers everywhere, from Nebraska to New York, and some even set up branch offices in Washington, D.C. to get their stock directly to troops. But the business wasn't without its risks. Samuel Upham of Philadelphia printed not only Union envelopes but copies of Confederate stamps and paper money, claiming he was educating Northerners who were curious about their Southern brethren. The Confederacy convicted Upham of treason and sentenced him to death in absentia. “The money was counterfeit, from their point of view,” Boyd says. A Cincinnati printer was arrested for making envelopes showing Jefferson Davis, Boyd's research has uncovered, and as far away as San Francisco, a man's stock was seized because he possessed such items.

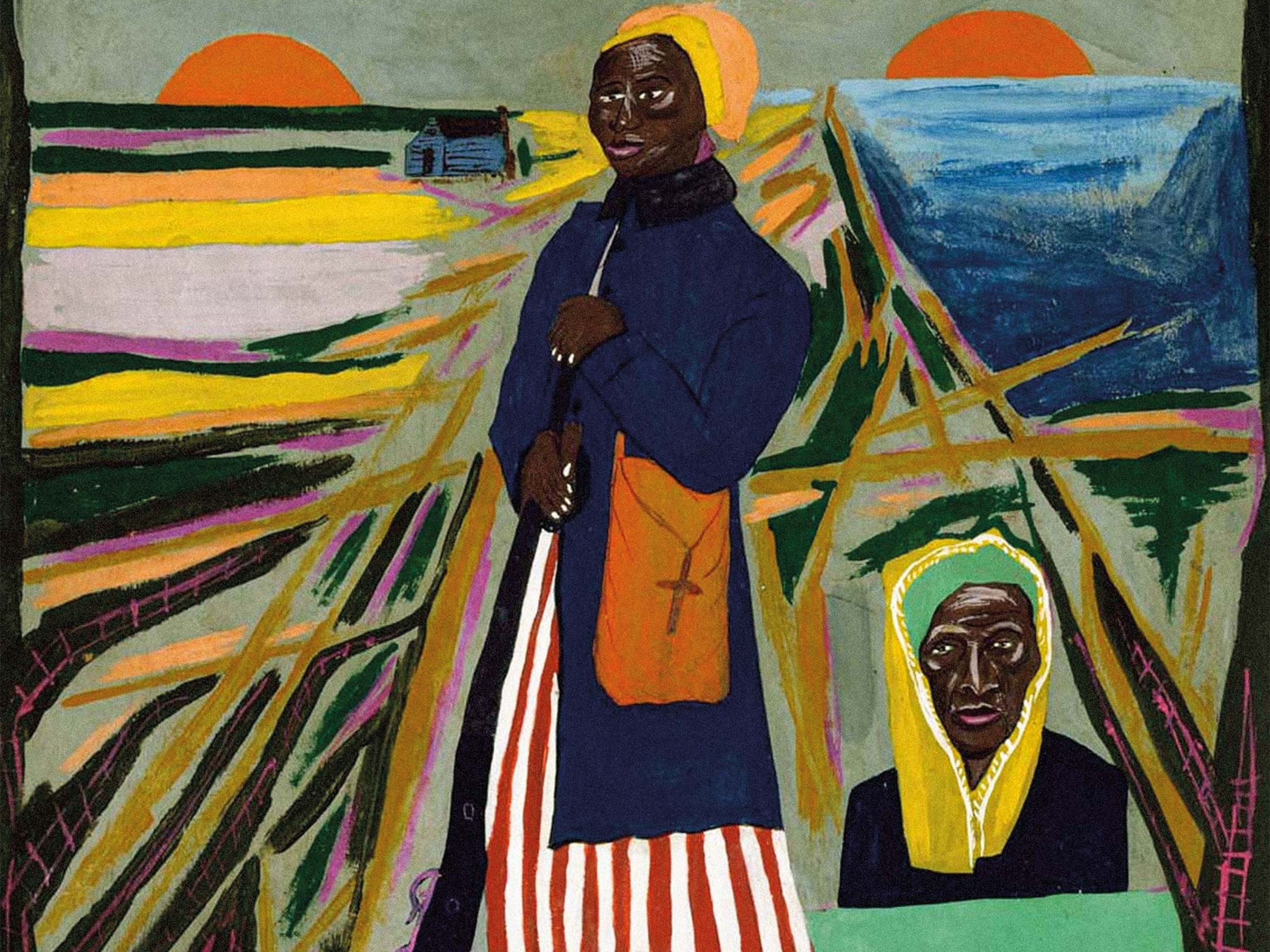

The envelopes from the North tended to pound away on a single theme: preserving the Union. Slavery does not come up frequently, and out of more than 10,000 designs, only about 80 depict African Americans at all, Boyd says.

In the South, pro-Confederate envelopes were being sold even before the first shots were fired, says Trish Kaufmann, a collector and expert on Confederate postal history. “They were the dissidents, the ones trying to drum up patriotic fervor” first, she points out. Envelopes featuring the original Confederate flag—with seven white stars on a blue rectangle and a red-and-white-striped background—flew off the presses. When new states seceded, rushed printers scratched in new stars or just small crosses on their plates to update the flag. But the South was not a manufacturing society, and it had to import its paper, as well as inks, from England and from the North. With a Union blockade keeping ships from reaching Confederate ports, paper was soon scarce, and by 1863, very few envelopes were being printed. As a result, there are envelopes with portraits of General P.G.T. Beauregard, an early Confederate hero, but none of Robert E. Lee or Stonewall Jackson, generals who rose to prominence in the second half of the war.

But the envelopes had a value beyond their ability to keep the rain off your words and show your opinions on the war. Huge numbers went directly from stationer's shelves into special souvenir albums. In fact, Boyd says that many of those that survive today were never used. And that relates to a mystery Boyd has yet to unravel, about a set of envelopes that began to appear only after the Civil War concluded. Printed on high-quality paper, these bear racist or anti-Lincoln sentiments, the kinds of things that were very rare among envelopes printed in the South while the war was going on. “We don't know a lot about this … but I've never seen one mailed,” he emphasizes.

Boyd hopes to dig deeper into the origins of these post-war envelopes by searching through digitized issues of a magazine called The Confederate Veteran, published for former soldiers, as well as Southern newspapers. He has a hypothesis that the printers might have placed ads there, intending their products to reach that particular market. The identities of the envelopes' makers are mysterious, but their products appear to have existed solely as souvenirs.