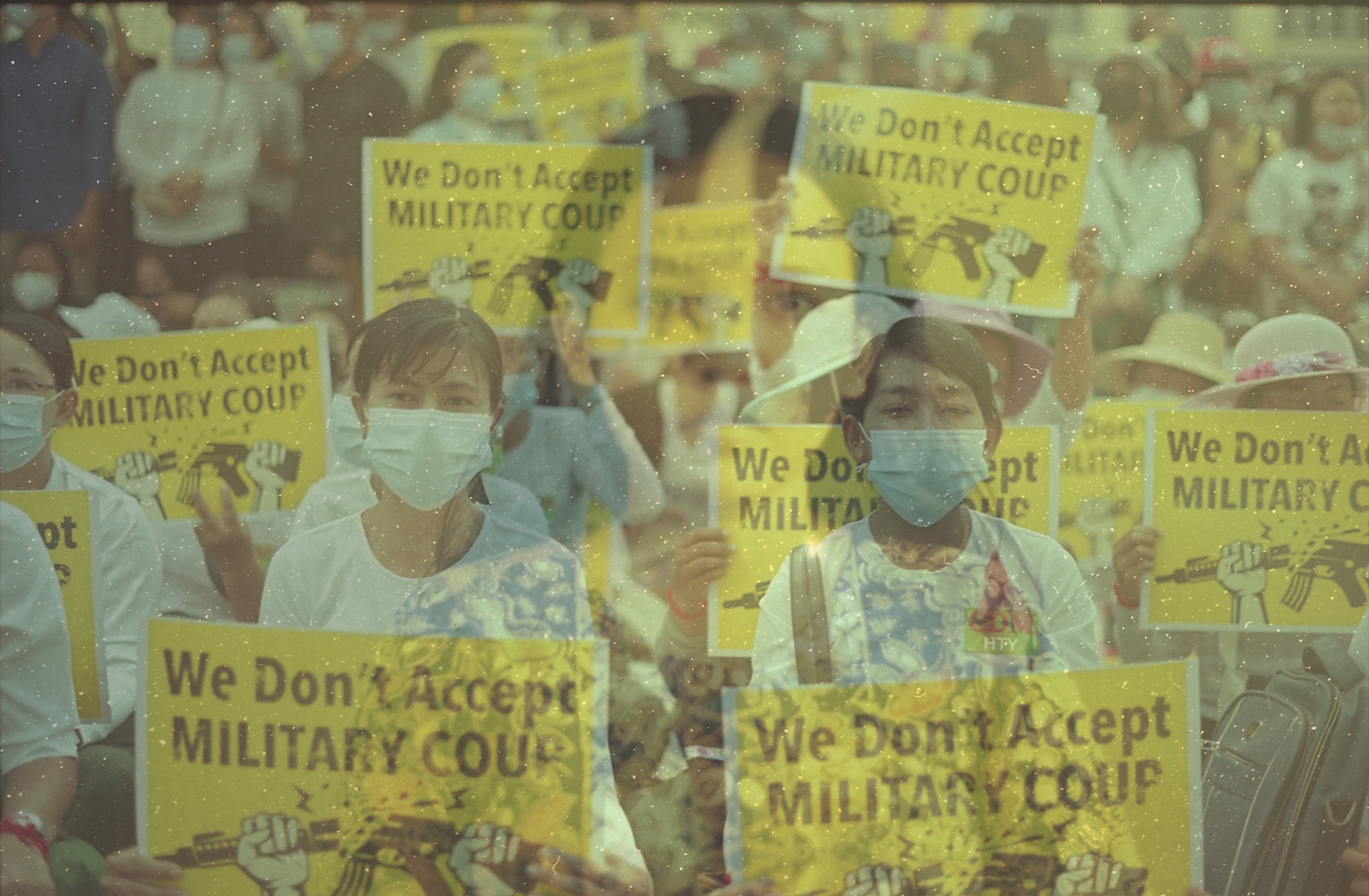

'I'm doing this for democracy': Protesters in Myanmar speak out

Behind the scenes with Burmese battling security forces, who explain why they're risking their lives.

Yangon, Myanmar — The military generals who throttled Myanmar’s fledgling democratic experiment in the wee hours of February 1 may not have counted on a major public backlash against their coup to nullify the results of the November 2020 election.

For the first few days, Myanmar’s population of more than 54 million people seemed stunned into silence. But by the fourth day, after police raids and arrests began, people flooded the streets in peaceful protests led by the youth of this conservative Buddhist nation. Even older citizens—who had endured five decades of ruthless military dictatorships and had tasted some freedoms during the past decade of hybrid democratic rule—joined in resisting with exuberant fury.

In the nation’s largest city, Yangon, tens of thousands of citizens stampeded into the streets on February 7. Battalions of medical students clad in white lab coats marched shoulder to shoulder. Food-delivery bicyclists pedaled along in formation. Long-marginalized groups—religious minorities, oppressed ethnic groups, the LGBTQ community—joined the angry protests. Young women spearheaded many of the demonstrations.

What began as a repudiation of the coup and a call for the release of the nation’s detained elected leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate whose refusal to condemn the genocide of Myanmar’s Muslim Rohingya minority tarnished her reputation internationally, quickly grew into a nationwide rebellion.

Within days, the military and police began shooting unarmed protesters. As of March 18, 224 people have been confirmed killed and 2,258 have been detained, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, an independent human rights group based in Thailand and Myanmar. The association also has tracked nighttime raids and mass detentions. The Guardian has reported the torture and execution of an opposition activist in custody.

Pro-democracy advocates have adapted to the bloody crackdowns by staging smaller, flash mob–style protests and coordinating nighttime sit-ins to distract police forces from their efforts to crush protest hot spots.

As thousands of protesters continue battling security forces behind homemade shields, we present their voices. Each portrait has been superimposed over a scene from the protests, and the protesters explain in their own words why they’re risking their lives at this moment in their country’s history. For their protection, we are identifying them only by occupation and age.

“I’m still hopeful we will win,” one activist told National Geographic. “If we don’t, then it’s over. Our future is gone.”

Video producer, 30

“I had a good job. I had big dreams for the future of my family. I have two daughters. They’re just toddlers. They are my life’s priority. Everything has collapsed with the coup. I don’t want my daughters to grow up under military dictatorship.

“My wife is on the street with me. We’re fighting the terrorists together. That’s what we call our military. They aren’t soldiers. They don’t protect us like normal soldiers do. They kill us. They destroy our property. They shout violent things at us: ‘**** your mother! We’re going to shoot you in the head!’ We expect more violence to come. They are very cruel. Of course we’re afraid.

“Worse days are coming. Everyone says this. They will start raiding our homes. They will start raping women and killing more people. We don’t have weapons. They have all the guns. But we have the youth. We have young people in every house. I think we can stay nonviolent for a year maybe. After that it will turn into a civil war. A genocide.”

Retired businessman, 63

“I have lived through many military crackdowns in Myanmar. I was an activist in all of those old revolutions. We had many strikes, many protests. We lost all of them. I had to go into hiding. I was imprisoned for four years. My whole family was imprisoned. I grew tired of all of this. I just wanted a quiet life. This time, I feel it’s a bigger revolution. It’s not about politics anymore, not about leaders or parties. It’s against fascism. We’re united now like never before. We can easily gather 500 people together fast. We’re protecting each other. Neighbor looking out for neighbor. My mind is there now—back in my neighborhood. After you photograph me, I need to return. They need me.”

Human rights advocate, 27

“I’ve protested with other LGBTQ women in front of embassies. In front of the U.S. Embassy, we chanted, ‘Save Myanmar. Support us.’ We wore similar skirts and wrote, ‘**** the Coup’ on our outfits. We denounced Russia in front of their embassy. In front of the Chinese Embassy, I held a poster that said ‘My father is Chinese, but I am against the Chinese government supplying arms to the Burmese military.’ Neither China’s nor Russia’s ambassadors came out and met us.”

Artist and writer, 41

“Art mobilizes people. We have a long tradition of that here in Myanmar—a history of protest art. Poets in Mandalay, the imperial capital, were writing rhymes against tyranny centuries ago. They compared repression to bitter cold. We can draw on that tradition. Art has a strong effect on people’s psyches. It’s a way to combat fear. That’s what artists have to do now, even when tear gas is burning our eyes.”

Interpreter, 37

“There’s a lot of discrimination against the disabled here. I was jobless for six or seven years. I finally got a job I like. But then the coup came. My company is closed now. So I’m protesting. I have joined other disabled protesters.

“At Tamwe ward, the police and soldiers came one morning and just started shooting at the students. They were using real bullets from G3 rifles. One young student standing next to me was shot in the arm. I carried him away from the scene. I could do that because I’m a big guy. (Laughs.) I’m not afraid of the police. You’re born, and then you have to die. I’m doing this for democracy.”

Businesswoman, 32

“My mom always talks about the hardships she faced during the last big uprising against the Myanmar military in 1988. She was four months pregnant with me. She was starving. She and her brother tried to escape to her hometown of Myitkyina without a train ticket, because they didn’t have money. She lived on a broken-down train for five days while she was on the run. They faced death. She says I might have to face this all over again. She told me, ‘You survived while you were still in my belly in the last revolution, but now you'll have to look after yourself.’ ”

Businessperson and LGBTQ activist, 30

“I was out protesting when the police threw tear gas bombs at us. A family in the neighborhood opened their door and invited me into their home. After a while, the police advanced. They were throwing more tear gas bombs and sound grenades. The house was completely covered in smoke, so I wasn’t able to see much. They came very close to me—I could see them up close. The homeowners told me to be quiet. The police came by later to retrieve empty canisters of tear gas bombs and sound bombs. They took away the spent bullet casings that they’d fired too.

“Rather than being scared, I’m angry. If I’m scared at all, it’s because I may not be able to control myself, and I may want to actually try to hurt the police. So I practice self-control. Even though I have constant thoughts of violence toward them, I tell myself to calm down. Only if all the people in the entire country are unified and coordinated in their efforts can the military dictators be uprooted. I don’t want to deviate from this goal.”

Research consultant, 28

“I’m a minority from Rakhine state. I’ve faced discrimination all my life. I knew I was different from about the fourth grade on. The teacher would slap me and not other students. I felt really, really small. My whole life, I’ve felt cast aside by the mainstream Burmese community. That’s why this revolution has to be total. We can’t go back to the old status quo. We need a new federal system that gives real power to ethnic minorities. That’s what I’m protesting for. This is an opportunity. I feel like I’m breathing for the first time in a long time.”

Labor activist, 35

“I’m pregnant right now. I feel exhausted after I walk on the streets. But I don’t want to stay at home. When I see posts about protests on Facebook, I feel guilty about staying at home.

“It’s true that most protesters are demanding the immediate release of Aung San Suu Kyi. Is it enough that she’s released? We may share political goals, but the problem is much bigger. It’s our country’s old system of authoritarianism. We need to consider the rights of ethnic minority groups, the issue of majority Burmese chauvinism, and many other things.

“Before the coup, my friends encouraged me to have a child because of my age—I’m getting older. At first, I was happy and proud that I was going to have a baby. Now I’m not sure. I don’t welcome a child anymore because of what’s happening in my country. The future is too uncertain.”

Yu Yu Myint Than is a documentary photographer from Myanmar. Much of her work explores religious and women's issues.

Paul Salopek is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who is walking across the world for a project called the Out of Eden Walk.

The story, which was published originally without bylines for the safety of the contributors, has been updated to include their names.