'I sing about my fears.' Damon Albarn on turning the atmospheres of England and Iceland into music

Far from the high-volume of Gorillaz and Blur, the London-born musician’s ‘cathartic’ new work reflects on the elements, the poetry of John Clare—and the uneasy relationship between humans and nature in the shadow of COVID-19.

On 26 January 2016 around 400 people gathered in the church of St Michael and All Angels, in the tiny village of Stokenham on England's South Devon coast, to mark the centenary of a disaster.

In 1896, a government contract was awarded to Sir John Jackson Ltd to dredge shingle from the coast of nearby Start Bay to feed concrete for a Plymouth dockyard. The human and environmental consequences were elbowed aside in favour of lucrative progress—much to the alarm of the village of Hallsands, off which the dredging was taking place. Home to some 150 residents in 37 houses and a pub, by 1900 the fishing village had already seen the level of its beach drop due to the depletion of the shingle, and a high tide breach its sea wall.

Desperate, the residents petitioned for the dredging to stop—which, in 1902, it finally did. The following years saw some natural recovery of the beach, but it wasn't enough. On the evening of 26 January 1917, an intense storm caused a tidal surge. Unobstructed by the depleted shingle, the sea battered Hallsands to pieces. By morning, most of the village was gone—its residents alive, but homeless. A cautionary tale, if one were needed, that human pillaging of the environment can backfire in unexpected ways.

A century later and a mile down the coast from the remains of what's now called old Hallsands, filling the pews of the chilly 600 year-old church that evening in 2017 were the usual parishioners, local dignitaries, descendants of the villagers themselves— and, discreetly clad in a flat cap and black duffel jacket, one internationally famous musician.

Quizzed by a journalist after the service as to why he was there, Damon Albarn—lead singer and songwriter of British group Blur, and Grammy-award winning anime-band Gorillaz—revealed he owned a house nearby. Of the crumbling coastline and its human-battered history, he said: ‘it’s a place I go to think… I feel connected to it. It’s inspired me.’

(Related: See inside Italy's ghost villages.)

One less positive aspect of this inspiration was articulated in the Gorillaz album Plastic Beach, released in 2010 at the peak of the 'virtual' band's fame: an environmentally-veined statement piece which Albarn described to BBC Radio 4's Today programme as “the beginning of a meditation on the state of our oceans.”

Now, the 53-year old musician's experience of spending lockdown overlooking this same coast—as well as another he calls home, outside Reykjavik in Iceland—has culminated in a new album of naturally-charged, intimate music. All inspired, he says, by the outlook from these two seemingly disparate vantage points. But according to Albarn, speaking to National Geographic (U.K.) via Zoom from his London studio, the two are—like everything else—connected.

Tell us about your connection with Iceland.

National Geographic is actually the reason I went there in the first place. There was an article about black sand beaches [in Iceland]. I’d had recurring dreams as a child about flying over black sand beaches… so when I made that connection, I thought ‘well, I definitely have to go there.’ So I took my typewriter and guitar and booked into a hotel, and very quickly realised that it was a very special place. I was so lucky—I went pre-tourism. Now there’s a bar to drink at in the middle of the blue lagoon. When I first went there was just a wooden hut to change in. And that’s all in 20 years.

What inspired you about that place in particular?

The space. I’d never been somewhere that had so much empty space. Where you could easily escape humanity. You could be in a bar in Reykyavik then half an hour later you could be in the most deserted kind of place you can imagine. The whole genesis of [this album] really came from wanting to make a record staring out of my window in Iceland. And that evolved into a series of workshops with some fantastic musicians, in collaboration with my friend Andre de Ridder, the conductor and orchestral arranger. We gathered in my house during various seasons. During the darker months, we’d get there around half nine, everyone would have a coffee, then get in place and we’d literally just play as the day emerged.

Right back to Blur's Parklife, your songs have always been products of their time in terms of the stories they tell. What story were you telling with this album?

Initially it was just, ‘how far can you take an ensemble into nature without literally abandoning your instruments and just being in it?’ It was about getting people to be really sensitive to the way the water changed, the clouds came in, the light, the rain… almost horizontal rain, then very gentle rain, almost mist. Or moments where a storm would come in, and the temperature would drop really dramatically and the rain would turn to snow, and amazing things like the northern lights appearing. (Related: Whales, Arctic lakes and myths: Check out Iceland's new road trip.)

Then the wildlife. The habits of the wading birds, the seals, the occasional whale that would be out in the bay. And the physical landscape: the mountain Esjan, and far in the distance the glacier and volcano of Snæfellsjökull. Just a wonderful tableau to meditate on. It was amazing really. Once people accepted that there were no written notes, and everything was driven by the actual dynamic of the environment, the music started to emerge. And I suppose the songs are sort of an articulation of that experience.

How do you go about turning what you see into sound?

That’s just, you know, the joy of making music and playing with your environment while you’re making it. These strange synapses that create weird thoughts and images.

How did the pandemic inform it?

In lockdown, it did enable me to sort of travel, to go back to places that were haunting me. Like the desert in Iran, or the tower of Montevideo [the Palacio Salvo, a building in the south American city designed by Italian architect Mario Palanti in the early 1930s]. So in that sense it was a unique record. Inevitably if you spend days and days looking out of the window, either behind it or outside, you just really tune in to that small space and that perspective looking out-out-out.

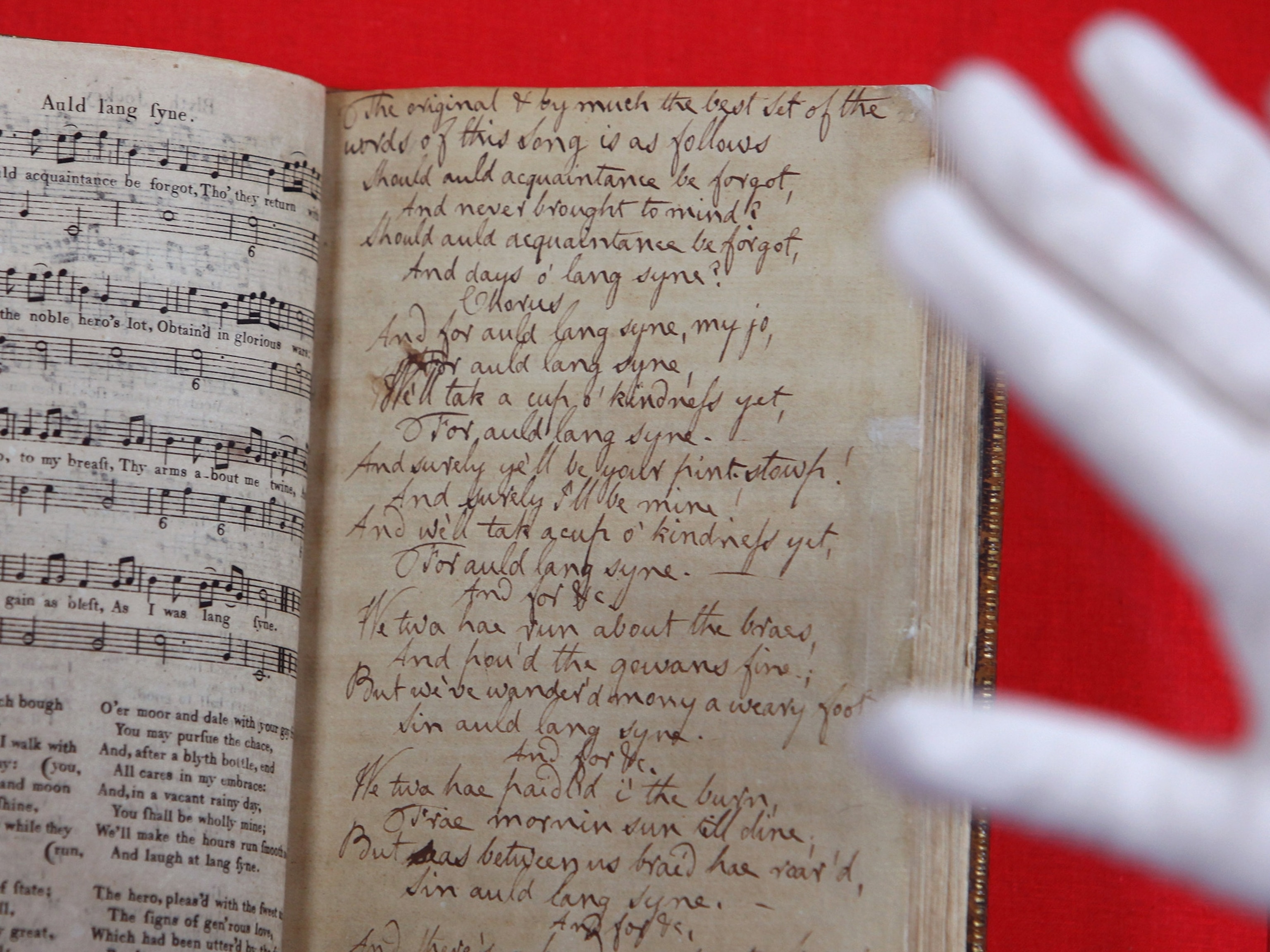

The album title is from a John Clare poem, Love and Memory...

I’ve always loved John Clare, from an anthology my mum gave me as a teenager. That one line, The nearer the fountain / More pure the stream flows, was my starting point, really. I didn’t really see it in the context of the poem at first, but when I started thinking ‘I’m going to turn this into an album of songs,’ various things – loss, my own personal loss during the pandemic—it just felt like the poem came to resonate louder and louder to me. Even though it was written at the beginning of the 19th century it felt very of the moment to express that kind of sentiment.

That poem has a lot of joy, but deep sadness too.

It oscillates, doesn’t it? From despair, to joy, constantly with each line. Very black and white all the time. That feels very how the music on the record feels to me. Water-bound somehow, always connected to the tides, and the atmospherics you experience when you’re by the sea. And between Iceland and Devon, over the last year I was by the sea all the time. [In Devon] I was swimming almost every day, trying to keep that connection with water. The song The Cormorant… there is a cormorant that fishes off that beach every day. That was lockdown on the beach, that song. Hours of just daydreaming.

I’ve been visiting that beach now for 25 years, I can associate every part of my life with it, from kids growing up, my daughter’s first tentative paddling in the water... everything really. I was so lucky in the last year, I’ve really got to know the residents, the fishermen. It felt like home for me.

We are starting to accept that we are tipping over an edge. But our cultural expectations and dreams are still massively incoherent to the reality of what we need to do.Damon Albarn

Have you seen the coast change during the time you’ve spent in South Devon?

It’s receding constantly. Sometimes all the shingle is taken and you can see the petrified forest underneath. And sometimes this terrible plastic rubbish comes in. It makes you so aware that out there, there’s these currents bringing this stuff from all over the place. You go down one morning after there’s been a storm and it’s just a rubbish heap, and you just have to start clearing it up. And then a week later, it all disappears again, and you feel like everything’s OK in the world, but it’s gone somewhere, hasn’t it? It’s back out there in the currents and it’s been taken somewhere else. That’s where the idea for Plastic Beach came from, that beach. It’s somewhere where I feel a lot can be learned.

That album made a keen statement about plastic in the ocean...

Definitely at the time [2010] it wasn’t really something people were responding to. I’d seen the plastic, I read about it, imagined what we were doing. And even then it was a massive problem. The idea of these vast, matted plastic semi-islands floating around in the Pacific. Very different to the experience on that Devon beach, but nonetheless connected.

(Related: We made plastic. We depend on it. Now we're drowning in it.)

Like anything, if you meditate on anything in the natural world for long enough, it can tell you everything about where we’re at. Everything that we put in there comes back.

The Hallsands disaster is perhaps a good example of that.

Oh no, absolutely. The history of Hallsands is a perfect story of what man is doing and what has been doing for a very long time. We see environmental and man-made environmental change as a modern thing, but it’s been going on for hundreds and hundreds of years.

How does that make you feel?

It’s a madness. Collectively, we are definitely mad. Until we start to embrace our collective responsibility, and start to see ourselves as everyone, and see the Earth and our relationship with it as [like] how we care for our family. It’s almost immaterial if we don’t apply the same sensitivity to the bigger picture. Because it's so connected.

Have you always had this attitude?

My mum in particular has always been sort of an advocate of simplicity. I've inherited from her to a degree. I hated it at school—I'd have recycled clothes and stuff. She even had me eating carob in the 1970s... when everyone [else] was having Space Dust. Her family were farmers originally, so there is that sense of commitment to the land, that what you put into it is what you get out. Certainly she has always been very quick to remind me if I’m doing something that’s at odds with our bigger environmental commitment. I try to live down there [in Devon] in a simple way.

Are you hopeful for humans? As a species?

I’m hopeful that eventually we will realise how fragile everything is. [But] there’s so much noise. Social media is not helping, because… it stops... a whole new generation just listening, and being quiet, and not having anything other than what’s around them. They just have what’s in front of them in their hand [mimics a phone], and everything that comes out of that—the energy that comes out of that—it’s a kind of massive great joke. The amount of energy that’s needed to fuel the mechanics of social media is exactly what we shouldn’t be doing.

Everyday Robots, from your last solo record, includes the lines: We are everyday robots on our phones... looking like standing stones.

Yeah. I sing about my fears. It’s cathartic for me to sing about what I imagine could happen... if things become how I imagine them. It’s about tipping points. We are starting to accept that we are tipping over an edge. But our cultural expectations and dreams are still massively incoherent to the reality about what we need to do.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity, and was adapted from the National Geographic U.K. website.