2018's deadly hurricane season, visualized

From above the Earth and on the ground, photos and mapping help explain why this year's storms were so destructive, and what may come next.

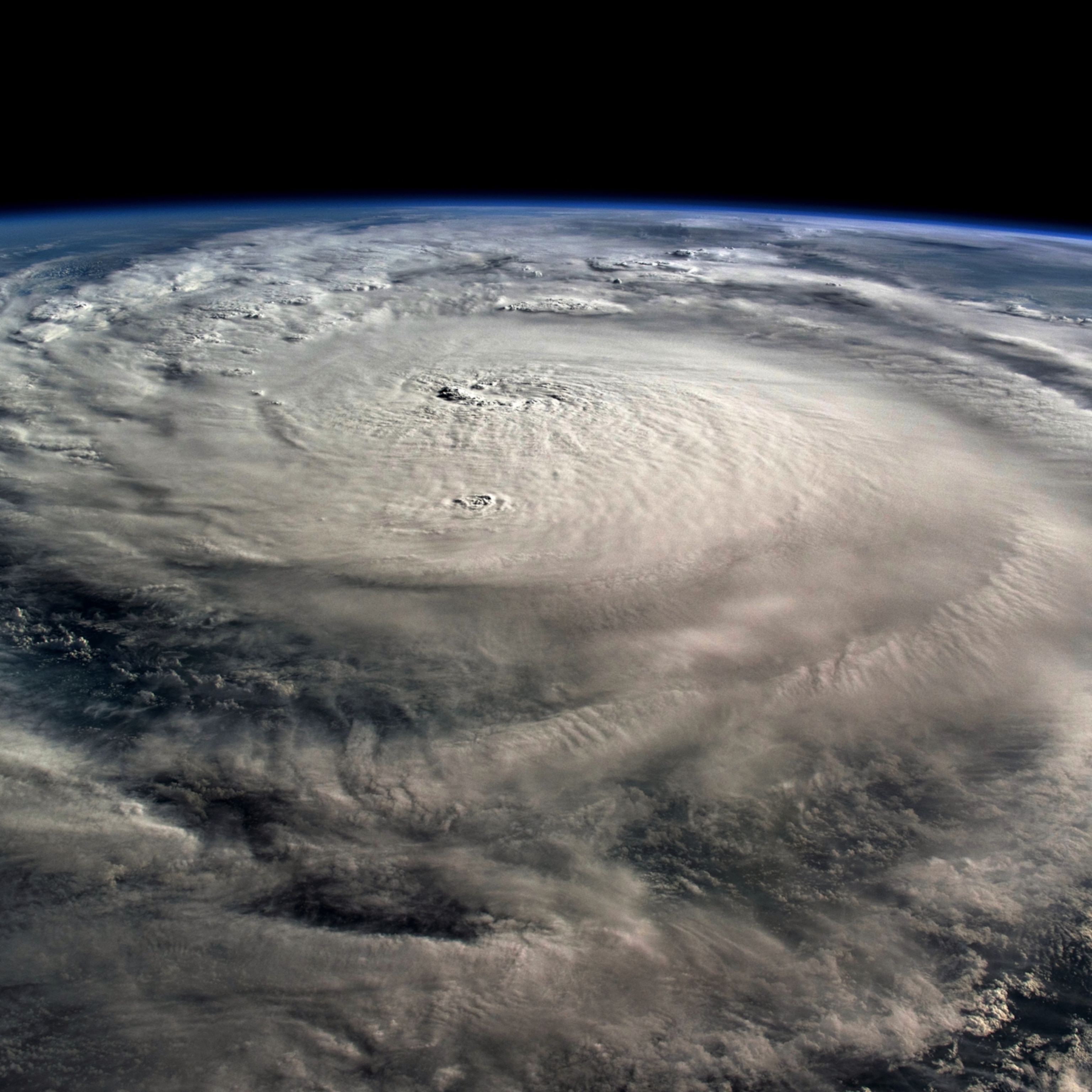

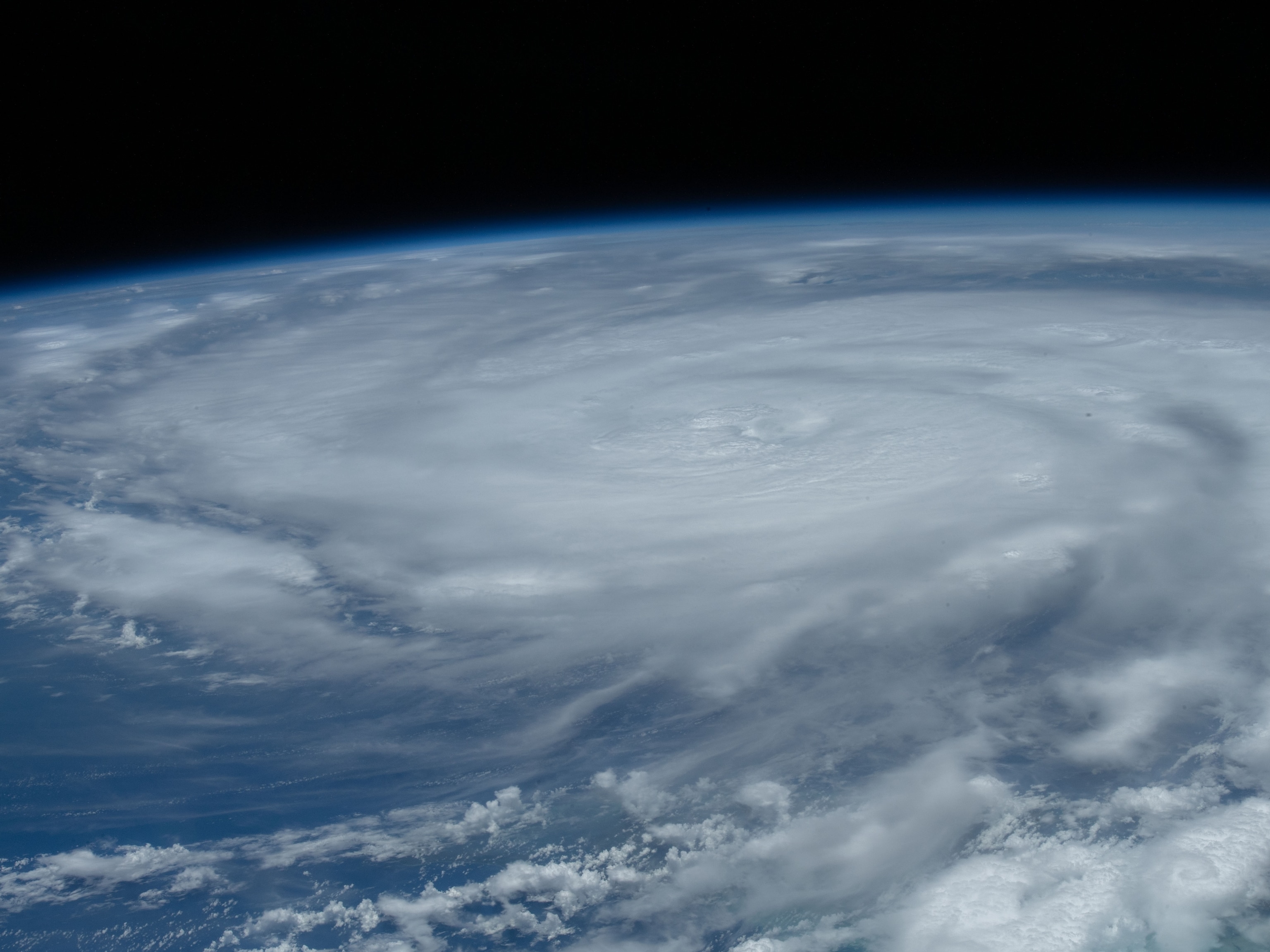

Over the span of just 70 days, 22 major hurricanes struck land around the Northern Hemisphere in 2018. They began earlier, continued later, and some took unexpected paths before hitting land. Between record-breaking hurricanes in both the Atlantic and Pacific, billions of dollars in damages were seen.

All told, 2018 was one of the most active hurricane seasons on record, and some studies are speculating that a warming climate may be making these storms more frequent and more intense.

A number of factors, however, can determine the strength of a hurricane when it hits land. Over the course of weeks, tropical storm systems must gather strength, survive wind shear, and pass over land obstacles before striking land as a hurricane (learn more how hurricanes form).

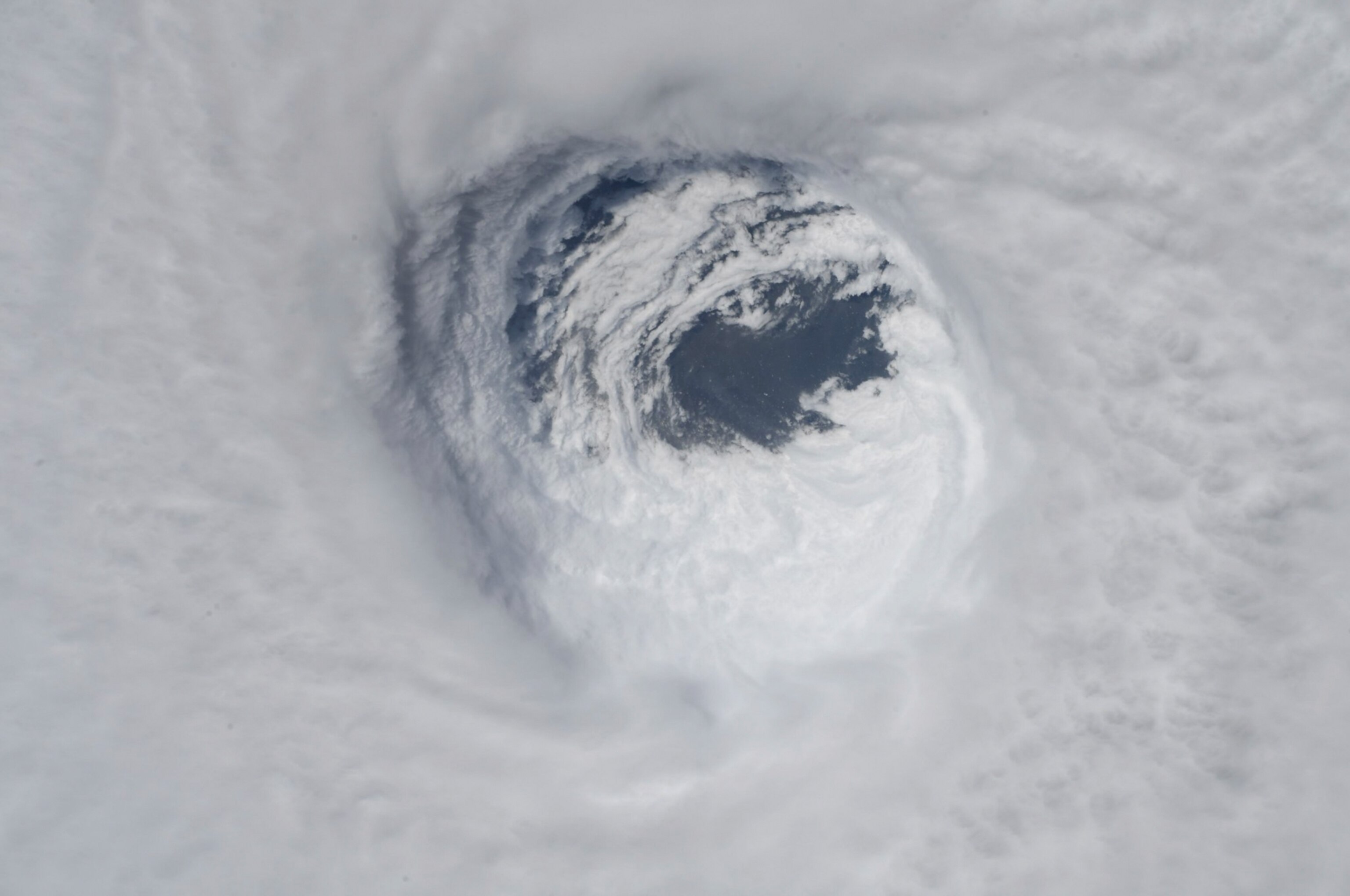

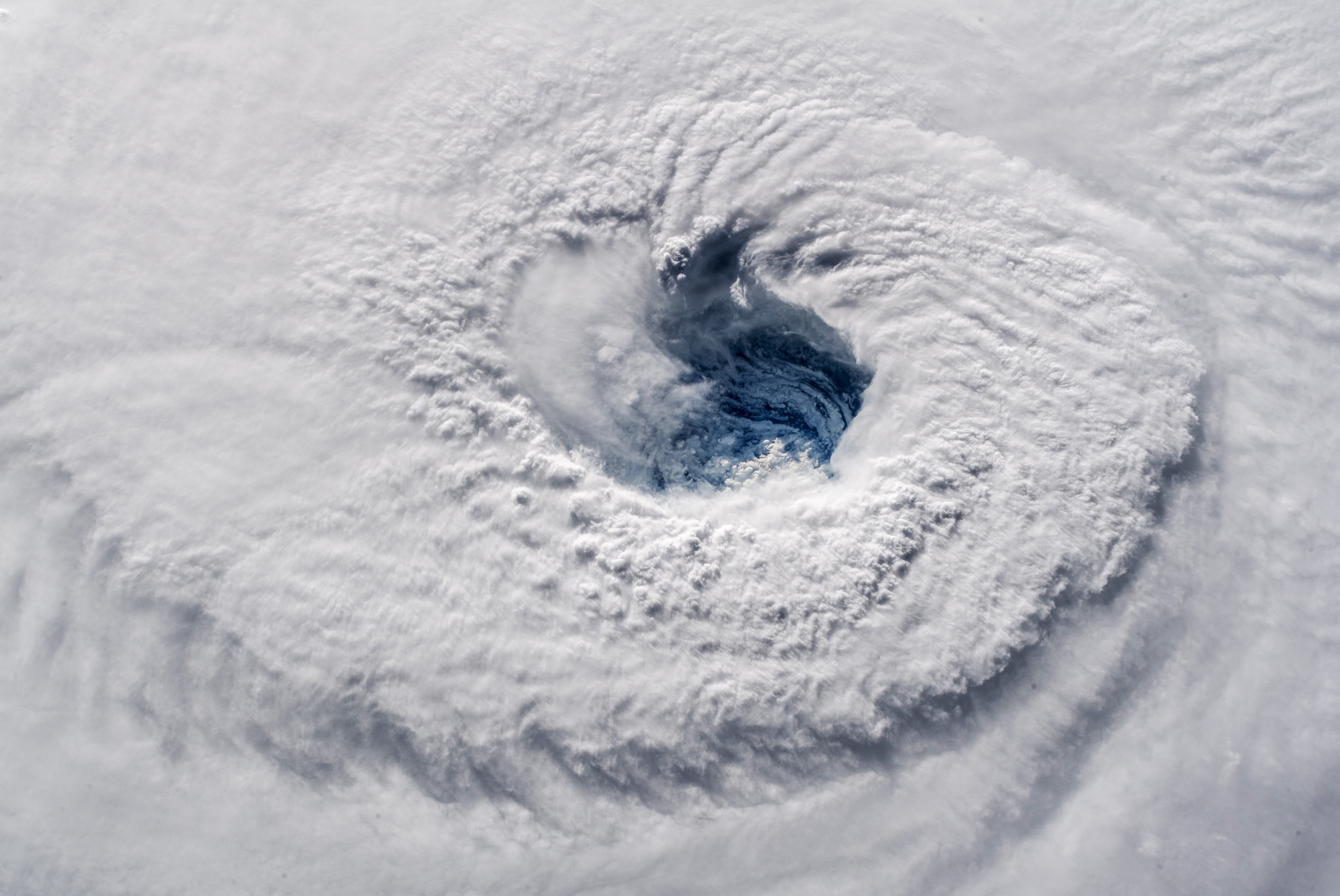

Thanks to satellite monitoring, scientists are able to see storms play out, a capability that will help them understand how storms might be changing. Below, see the paths 2018's worst storms took toward devastation (learn about the strongest storms in history).

North Atlantic

One of the wettest storms on record, Hurricane Florence developed in mid-September and made landfall over the Carolinas on September 14. Florence had slowed to just a Category 1 by the time it hit, but it carried with it intense amounts of water that led to disastrous rainfall. The storm, which developed off the coast of west Africa, was warm, meaning it carried more moisture than cooler storms. As it stalled over the south east U.S. coast, more than 30 inches of rain fell in some regions. At the height of the storm's impact, more than a million people were without power. Resulting from the storm's onset and lingering impact, 48 people died and damages topped $60 billion.

Hurricane Michael hit the Florida panhandle as a deadly Category 4 storm. It was one of the strongest to strike Florida in a century and the third strongest storm to hit the U.S. Wind speeds were as high as 155 miles per hour in Florida and Georgia. As the storm headed west over the Caribbean, it initially slowed down, but the warmer-than-average ocean water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico fueled Michael, making it stronger. A week after the storm hit, 34 people had died, and more than 1,000 were missing. Officials noted it could be months before the missing were completely accounted for, but damages are estimated to total $30 billion.

Slowing of the Storms

One of the most dangerous things a hurricane can do is slow down. Meteorologists warn that the Saffir-Simpson scale, the rankings classifying hurricanes on a scale of one to five, isn't the best indication of how dangerous a hurricane could be to the residents living in its path. As seen with Hurricane Florence, slow-moving hurricanes can stall over land, ushering in devastating flooding that can last for days.

A study published this summer in the journal Nature found that, on average, hurricanes have slowed by 10 percent since 1949. Those moving in the North Atlantic ocean had slowed by 20 percent. It's thought that a warmer atmosphere weakens tropical circulation, meaning hurricanes could become slower and rainier in the future as the world continues to warm.

Eastern Pacific

Hurricane Lane hit Hawaii in late August as a Category 5 storm. As Lane moved south east days before it hit Hawaii, it put the island chain in a tragically well-aligned position to ensure all islands would be hit. Hawaii is frequently grazed by dangerous tropical storms, but it's rare for it to be directly hit by a hurricane. On Hawaii's Big Island, some regions saw rainfall totals as high as 35 inches, and damage resulting from the storm is estimated to surpass $10 million.

In late October, Hurricane Willa was one of the strongest hurricanes to hit Mexico's western state of Sinaloa. Though it had weakened to a Category 3 when it hit Mexico, Willa brought with it intense rainfall. Like many of the hurricanes seen in the 2018 season, it had explosive growth before it hit Mexico. In less than 24 hours, wind speeds grew to 80 miles per hour. More than 7,000 people were forced to evacuate, and homes were left without power for days.

One of the most dramatic impacts from this season's hurricane season came after Hurricane Walaka nearly erased an entire Hawaiian island in late October. Though small and remote (only half a mile long and 400 feet wide), the island was home to endangered species like monk seals and green sea turtles. A sliver of the island has since reemerged since the hurricane swept through, but likely won't be enough to provide dry ground to the animals who use it for vital things like birthing offspring. Rising sea levels had been increasingly putting the island at risk of disappearing, and the Category 5 Walaka pushed it over the edge.

Western Pacific

Be it a typhoon, cyclone, or hurricane, each of these names are referring to the same storm system in different locations. Storms in the western Pacific Ocean are called typhoons, storms in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean are called cyclones, and storms in the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific are called hurricanes. Scientists often refer to all three as simply “tropical cyclones.”

Chaos reigned in the days after Super Typhoon Mangkhut struck the Philippines and China. The storm made landfall as a the equivalent of a Category 5 hurricane and caused over 60 deaths upon impact. Many were the result of landslides caused by the sudden deluge of rain. Mangkhut was one of the strongest storms seen in 2018. Its wind speeds topped 165 miles per hour, 75 miles faster than Hurricane Florence. A growing human population along coastal China is leading to more residential and business development. Financial damage from the storm is estimated to be more than $30 billion U.S. dollars.

Though it received little attention from U.S. media outlets, Super Typhoon Yutu was described by meteorologists as the strongest storm of 2018. It struck the U.S. territories of the Northern Mariana Islands, including Tinian and Saipan, which sit in the eastern Pacific Ocean just north of Guam. Yutu's wind speeds topped 180 miles per hour and created storm surges as high as 20 feet. Like Hurricane Michael in the Gulf of Mexico, Super Typhoon Yutu took meteorologists by surprise as it rapidly intensified over the Pacific. It was one of the most destructive storms the islands' residents have experienced. Large swaths of the islands' key infrastructure was destroyed in what emergency responders described as the worst storm they had ever seen.