Cortisol rises during intense workouts. Is that really a bad thing?

Low-intensity exercise is thought to be better for keeping this “stress hormone” in check. But scientists say cortisol plays a crucial role in fueling your workout.

Fitness influencers claim intense workouts such as HIIT or running can spike cortisol and hinder weight loss, while gentler alternatives like walking keep it in check. But cortisol’s role in exercise is far more than simply “good” or “bad.”

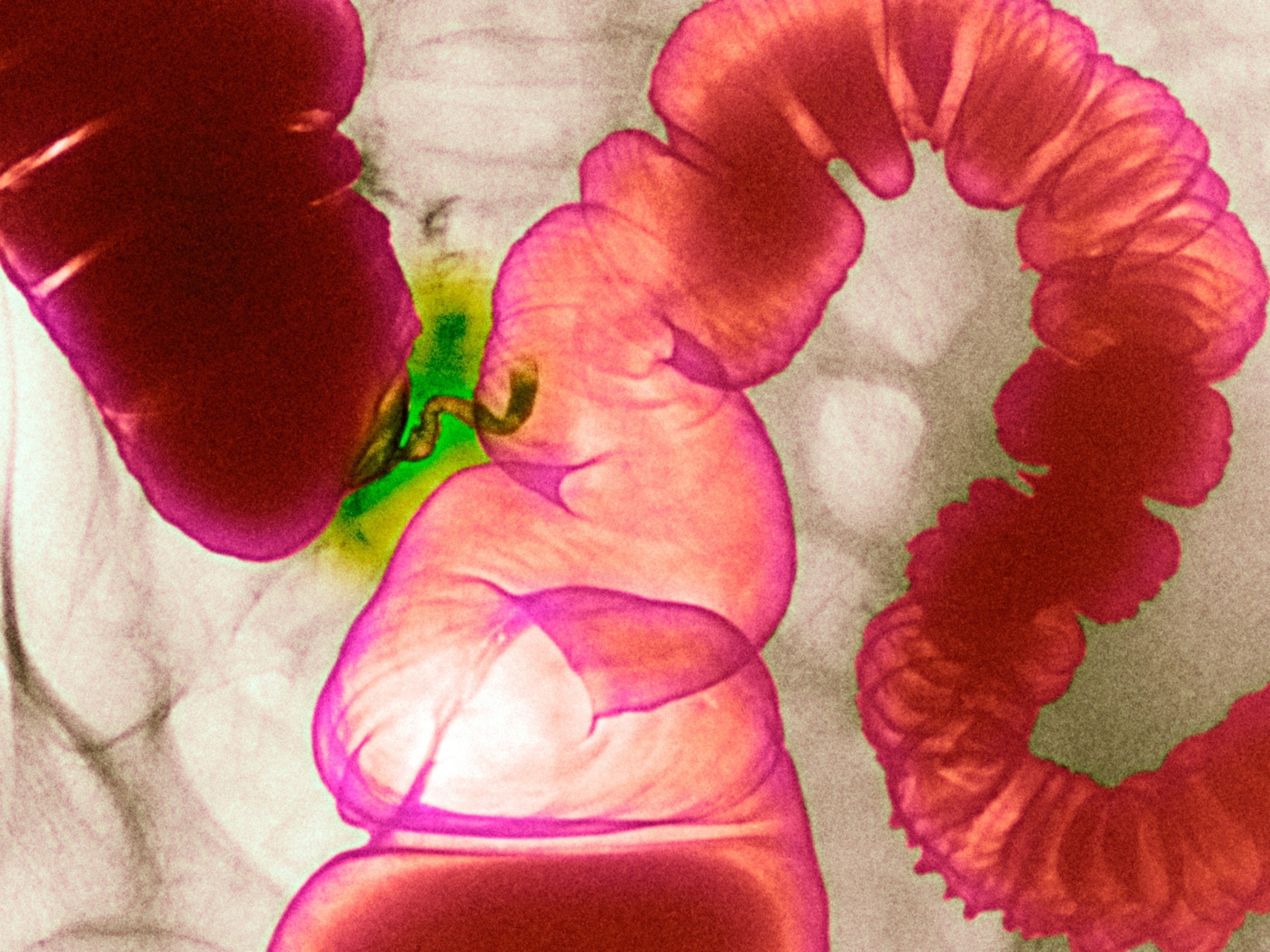

Often branded as the “stress hormone,” cortisol is blamed for everything from belly fat to burnout. But it plays a crucial role in keeping the body running. “If we don’t have cortisol, we die,” says Martine Duclos, an endocrinologist and physiologist in sports medicine at Université Clermont Auvergne. It helps mobilize energy, suppress inflammation, and maintain blood pressure in stressful situations.

So, if cortisol is essential, why does it have such a bad reputation? And does exercise send it spiraling out of control? Here’s what the science actually says about this misunderstood hormone—and what it means for your workouts.

How exercise affects cortisol

Cortisol doesn’t just react to stress—it follows a natural daily rhythm. Levels are highest in the morning to help us wake up and be alert, says Travis Anderson, a research scientist at the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee who has investigated cortisol as a circadian hormone. Throughout the day, cortisol gradually declines unless the body encounters stressors—like exercise—that temporarily push levels higher.

Despite cortisol not being inherently harmful, persistently high cortisol levels can contribute to high blood pressure, cardiovascular issues, and metabolic dysfunction. In extreme cases, such as Cushing’s Syndrome, the body produces too much cortisol, leading to increased fat accumulation, a predisposition to type 2 diabetes, and other health complications.

Why cortisol rises during exercise

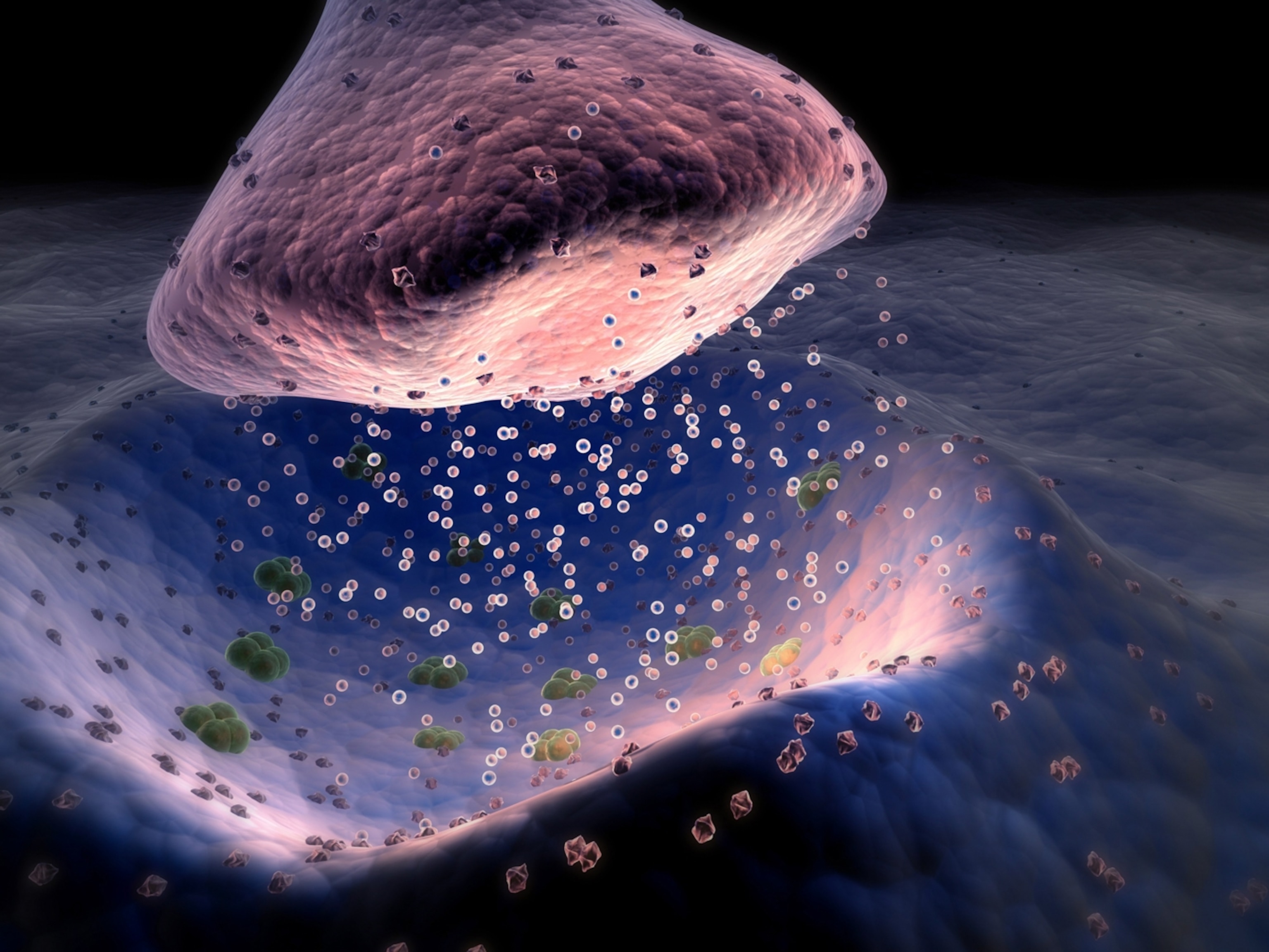

Since exercise is a form of stress, cortisol naturally increases during physical activity. But this isn’t a bad thing—it’s a key part of how the body fuels movement. Anderson explains that cortisol ensures enough glucose is available for muscles to keep working.

In a study examining 12 active men, researchers found that moderate- to high-intensity cycling workouts triggered spikes in cortisol—a finding consistent with several other investigations. The study measured intensity using maximal oxygen uptake, or VO2 max, the maximum amount of oxygen a person can use during intense exercise. Sprinting up a hill, for example, would get close to 100 percent oxygen uptake. Cycling workouts at 60 and 80 percent of an individual’s maximal oxygen uptake led to increased cortisol levels, while a lower-intensity session at 40 percent didn’t.

(What’s your VO2 max? The answer could transform your health.)

“The higher the intensity of the workout, the greater the cortisol response,” says Anthony Hackney, a professor in exercise physiology and nutrition at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “Although you have to keep in mind it’s not infinite,” he adds—eventually, cortisol levels plateau. Aerobic exercise also spikes cortisol levels more than resistance training, such as weight lifting.

How long does cortisol stay elevated after exercise?

But how long does this surge last? Research shows that once the workout ends, levels begin to fall quickly. Duclos says the body has a built-in negative feedback loop that prevents cortisol from remaining elevated for too long. “After exercise, cortisol drops and the levels become similar to people at rest,” he adds.

In the cycling study, the cortisol level of the participants had nearly returned to baseline after 90 minutes. Extreme conditions don’t seem to override this recovery process. “Even super high intensity exercise that gets cortisol pouring out of your ears—if you recover, it’s going to come back down,” Anderson says.

Why low-intensity workouts lower cortisol temporarily

While high-intensity exercise temporarily raises cortisol, the study also found the opposite happens at lower intensities. Anderson says the workout doesn’t create enough demand to stimulate the adrenal glands to produce more cortisol.

Instead, tissues in need of cortisol absorb the hormone already present in the bloodstream, leading to a slight dip in measured cortisol levels. But once exercise reaches a certain intensity, cortisol production surpasses its uptake into cells, he adds.

(Here’s how low-intensity training transforms your body.)

In fact, persistent cortisol elevation is more often linked to inadequate nutrition than to workout intensity itself. Those on chronically low-carbohydrate or low-calorie diets may experience prolonged cortisol elevations, Duclos says. When the body chronically lacks fuel, it compensates by releasing more cortisol to break down fat, muscle, and even bone tissue for energy.

Why are influencers promoting low-intensity workouts?

Some people feel better or lose weight when switching to a lower-intensity routine. That’s because high-intensity exercise can be effective but also demanding, especially for those unaccustomed to it. “Most people, if they try to do high-intensity workouts, they can do it,” Hackney says. “But they’re not going to feel good because their body’s not used to it.”

Anderson adds that some people jump into intense workouts too quickly, pushing their bodies beyond their current capacity. As a result, lower-intensity workouts may feel better—not because of cortisol, but because they allow for better recovery, reduce injury risk, and make exercise more sustainable. “If you tolerate it better, you stay with the program, you do more,” Hackney says.

Yet, despite this, cortisol continues to be blamed for workout fatigue, weight gain, and poor recovery, mostly based on “bad scientific knowledge,” Duclos says. She points out that influencers can be persuasive when oversimplifying complex physiological processes.

We often want simple answers for health issues, but that ignores the full, complicated picture. “Cortisol often gets maligned,” Anderson says. “And the fact of the matter is that there is no single factor that is going to be able to explain a complex physiological organism such as a human body,” he says.