What can 200-year-old DNA tell us about a murdered French revolutionary?

Jean-Paul Marat was stabbed to death in his bathtub in 1793. Now, blood preserved from his assassination may reveal the disease that struck him down in life.

What do Emily Dickinson, Karl Marx, and Jesus of Nazareth have in common? They’ve all played a part in a popular parlor game. Retrospective diagnoses—thought experiments in which modern scientists use present-day diagnostic frameworks to suss out potential causes of historical disease and death—are a favorite game of would-be time travelers and a staple of medical conferences. The theories can range from plausible to wacky (Julius Caesar had epilepsy! No, wait—mini-strokes!). But until now, none have relied on DNA from the historical figures they were trying to diagnose.

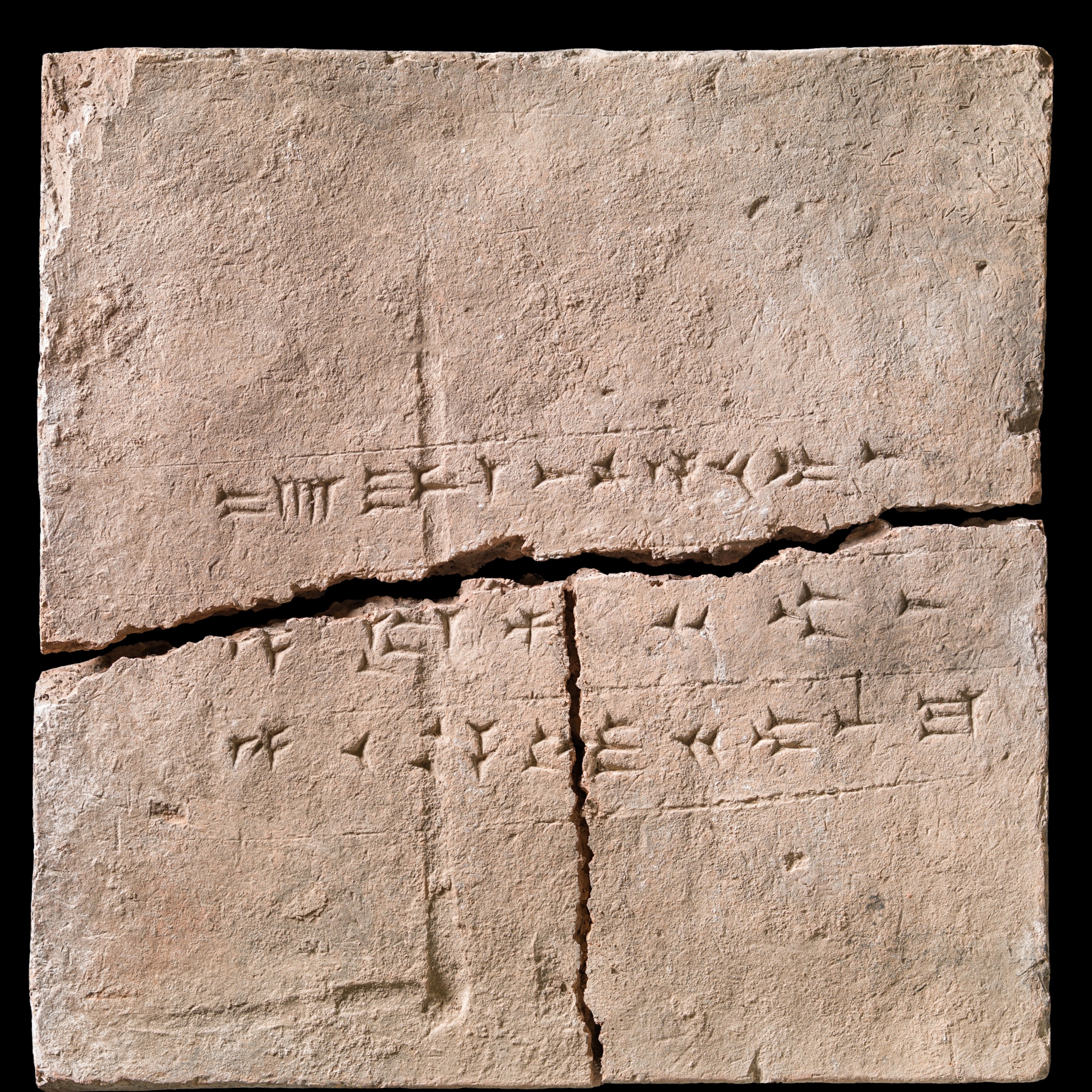

Thanks to a particularly violent murder, however, researchers think they have solved a medical mystery that vexed a notorious French revolutionary. To do so, they analyzed DNA from the 200-year-old crime scene, according to a preprint version of a study posted recently on bioRxiv. (The study has not yet undergone peer review.) The researchers write that the study is the first retrospective medical diagnosis to include the genetic analysis of a historical figure, and also the oldest successful retrieval of genetic material from cellulose paper.

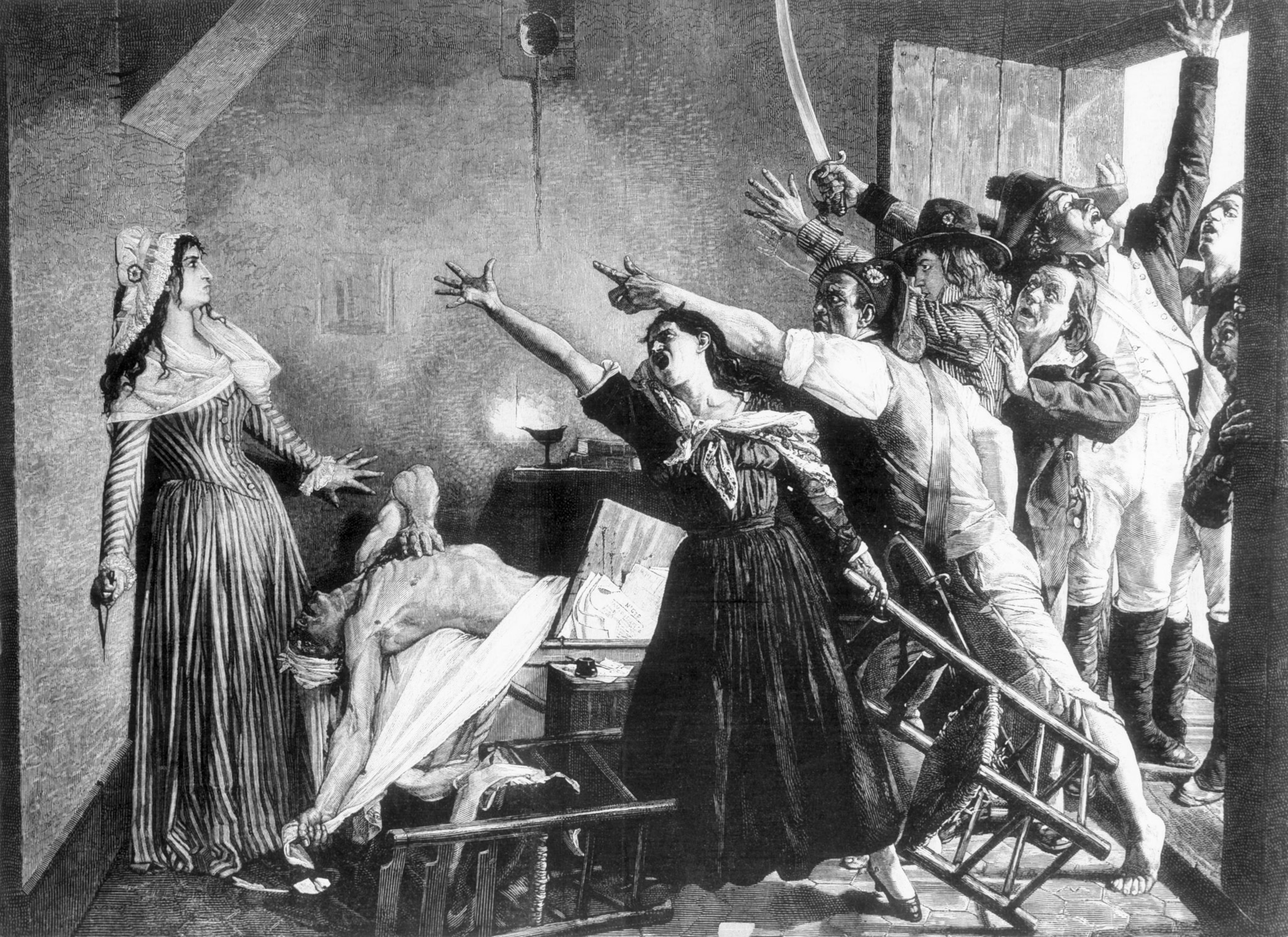

At its center is the blood of one of the most significant figures of the French Revolution, Jean-Paul Marat. During the 1780s, Marat’s searing pro-Revolution journalism and his paper, The People’s Friend, earned him the passionate support of poor Parisians—and plenty of pro-monarchy enemies.

Marat’s physical appearance was as polarizing as his radical political positions. He wore distinctive clothing—think dramatic robes, head scarfs and open shirts, which he adopted from working-class Parisians—and he had a visible skin disease. People recoiled from his blisters and oozing sores and chalked up Marat’s painful condition to everything from syphilis to a dangerous temperament.

Because of his incendiary opinions, the journalist often found himself on the run. He spent years hiding in attics and even Parisian sewers to escape his enemies. But by 1793, Marat finally had a stable home and a chance to treat his increasingly painful skin condition. Now, his skin turned him into a virtual recluse. He spent his last months writing and seeking relief for his itchy, blistered skin with long soaks in the bathtub, where he worked and visited with friends and guests. On July 13, 1793, the revolutionary was in the bath annotating newspapers when Charlotte Corday, a member of the Girondists, a moderate republican faction that opposed the popular violence Marat had helped stoke, burst in and stabbed him to death in the chest with a kitchen knife. Marat bled out within seconds.

The dramatic murder turned Marat into an instant revolutionary martyr, and his sister carefully preserved the newspapers stained with his blood, which survive to this day. Could the blood stains hold genetic clues about Marat’s skin condition? That question intrigued French forensic sleuth Philippe Charlier, a forensic scientist who investigates historic mysteries like whether Adolf Hitler is really dead or what really killed Richard the Lionheart. So he got in touch with Spanish paleogeneticist Carles Lalueza-Fox and asked him if it would be possible to analyze the DNA preserved in Marat’s blood-spattered newspapers.

To extract a sample without damaging Marat’s precious paper, Lalueza-Fox and colleagues took a cue from modern forensics, using the same types of swabs used at crime scenes to get samples of bloody paper.

An ancestral analysis confirmed Marat’s likely French and Italian ancestry. But DNA that didn’t belong to humans was even more intriguing. The team detected the DNA of several non-human pathogens on the blood-stained section of the paper, and used the presence of those microbes on the bloodstained portion of the paper to rule out many previous diagnoses floated as the source of revolutionary’s affliction.

Did Marat have syphilis, as suggested by his enemies? Nope, and he didn’t have leprosy, candida thrush, or scabies, either. Instead, Malassezia restricta, a fungus that can cause opportunistic skin infections, was a likely source of Marat’s misery.

The study wasn’t without its limitations: The DNA obviously wasn’t obtained while Marat was alive, and there’s no telling how many other hands touched, and contaminated, the paper over the years. And even if Marat’s contemporaries had known he had a fungal infection (or known about the germ theory of disease), they would have had no idea how to treat it.

Modern dermatologists might not, either, says Lalueza-Fox: Historical accounts suggest that the fungal infection, or a possible secondary infection contracted when Marat’s immune system was weakened by Malassezia, had reached an extreme that would rarely occur under modern medical supervision. “Even trained dermatologists would never have seen such an extreme example,” he says.

The research presents another vexing question: Is it even possible to diagnose someone with a skin condition using DNA? “That’s a tricky question,” says Lalueza-Fox. DNA can reveal genetic diseases and markers that point to the presence of other diseases, but when it comes to detecting the presence of infectious diseases, DNA diagnosis is still in its infancy. Lalueza-Fox thinks a fungal infection caused the skin disorder, but without an actual glimpse at Marat’s body and skin testing, it’s impossible to tell.

Even with DNA, diagnosing the long-dead revolutionary may never truly be possible. So why bother trying?

One answer is that health issues can influence the course of history—and Marat’s skin condition forced him to withdraw from the revolutionary movement in 18th-century France at the height of his powers. There’s no telling what he would have accomplished if he hadn’t been forced into skin-fueled seclusion, or all of those baths. Instead, Marat’s skin pushed him to the sidelines—and was so painful it affected his personality. “[The condition] might have influenced his decisions and the way he influenced history,” says Lalueza-Fox. “He was very, very sick.”

For Miguel Vilar, a genetic anthropologist and senior program officer for the National Geographic Society, the analysis is tantalizing. “I think it shows the power of the technology we have right now,” says Vilar, who was not involved with the study. “We can use paleogenomics to understand the past better.”

The analysis is the first time scientists have successfully used DNA to assist a retrospective diagnosis. Others have tried, but thorny issues of historical preservation and scientific ethics have held them back. A decade ago, for example, researchers tried and failed to get permission to analyze DNA from composer Frédéric Chopin’s preserved heart. (They analyzed it visually instead, and now think he suffered from tuberculosis.)

Perhaps the present study will inspire other attempts to reconsider historic figures using their DNA. But is it really possible to diagnose someone from across the centuries?

That’s unclear, says Sam Muramoto, a neurologist and senior scholar at the Center for Bioethics at the Oregon Health Sciences University who was not involved with the study. It isn’t unethical to use DNA or other methods to look back at a historical figure’s health so long as scientists keep living relatives in mind, he says. However, he sees these retrospective diagnoses as well-informed speculation.

“It’s a kind of professional disease,” Muramoto says. “When you have a hammer in your hand, everything looks like a nail.”