How a bloody battlefield inspired a pacifist to create the Red Cross

Swiss businessman Jean-Henri Dunant was shocked by the paralysis of local authorities after the Battle of Solferino, and then was inspired to create an international humanitarian aid organization.

In summer 1859, fields in Italy’s Po Valley were littered with human remains, and the soil was puddled with blood. Swiss businessman Jean-Henri Dunant had embarked on a trip to northern Italy hoping to meet with officials of Napoleon III, emperor of France, to settle problems related to land that he owned in Algeria—but he witnessed the Battle of Solferino instead.

The tragedy he experienced in Italy transformed Dunant into a humanitarian visionary and prompted him to co-found what would become the International Committee of the Red Cross. A lifelong pacifist, his conviction that warfare must be bound by internationally agreed rules led to the signing of the First Geneva Convention, which ushered in a new era in international law, imposing accountability on the actions of armed forces in combat zones.

(Was Napoleon Bonaparte an enlightened leader or tyrant?)

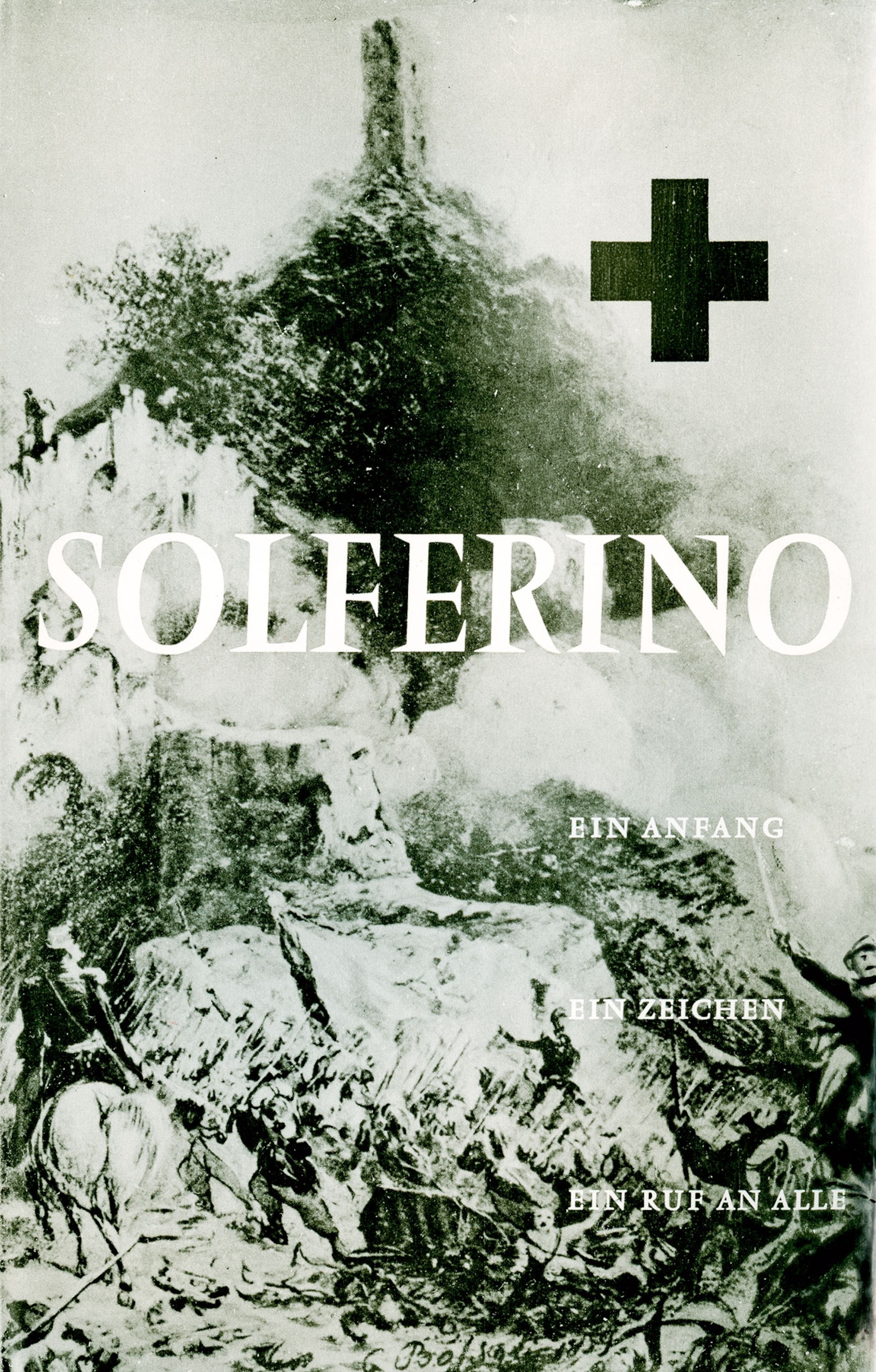

The hell of Solferino

Dunant’s business plans, and subsequent life and career, were transformed by the explosive geopolitics of Italy’s independence movement. France had allied with the Italian nationalists and was engaged in a bloody struggle to drive Austrian forces out of northern Italy. Dunant happened to arrive in the town of Castiglione delle Stiviere near Lake Garda on June 24, 1859—the same day the Battle of Solferino took place.

Solferino was a significant battle in many ways: It broke Austria’s hold over Italy and was the last ever military engagement where all sides were personally commanded by monarchs. It also entered the annals of military history for its deadliness: Following the single day of hostilities, thousands of soldiers lay killed on the battlefield. Austrian casualties alone numbered 22,000 dead and wounded. Dunant witnessed the bloodshed, and what he saw changed his life.“Oh, the agony and suffering during those days,” he wrote in his 1862 book, A Memory of Solferino.

In addition to the thousands of deaths, many more soldiers on both sides were wounded, and in the following days they began flooding into Castiglione. The whole town was turned into a makeshift hospital as locals opened churches, outbuildings, and private homes to accommodate the injured. The streets resounded with cries of the wounded soldiers as residents scrambled to help them, gathering blankets and improvising stretchers.

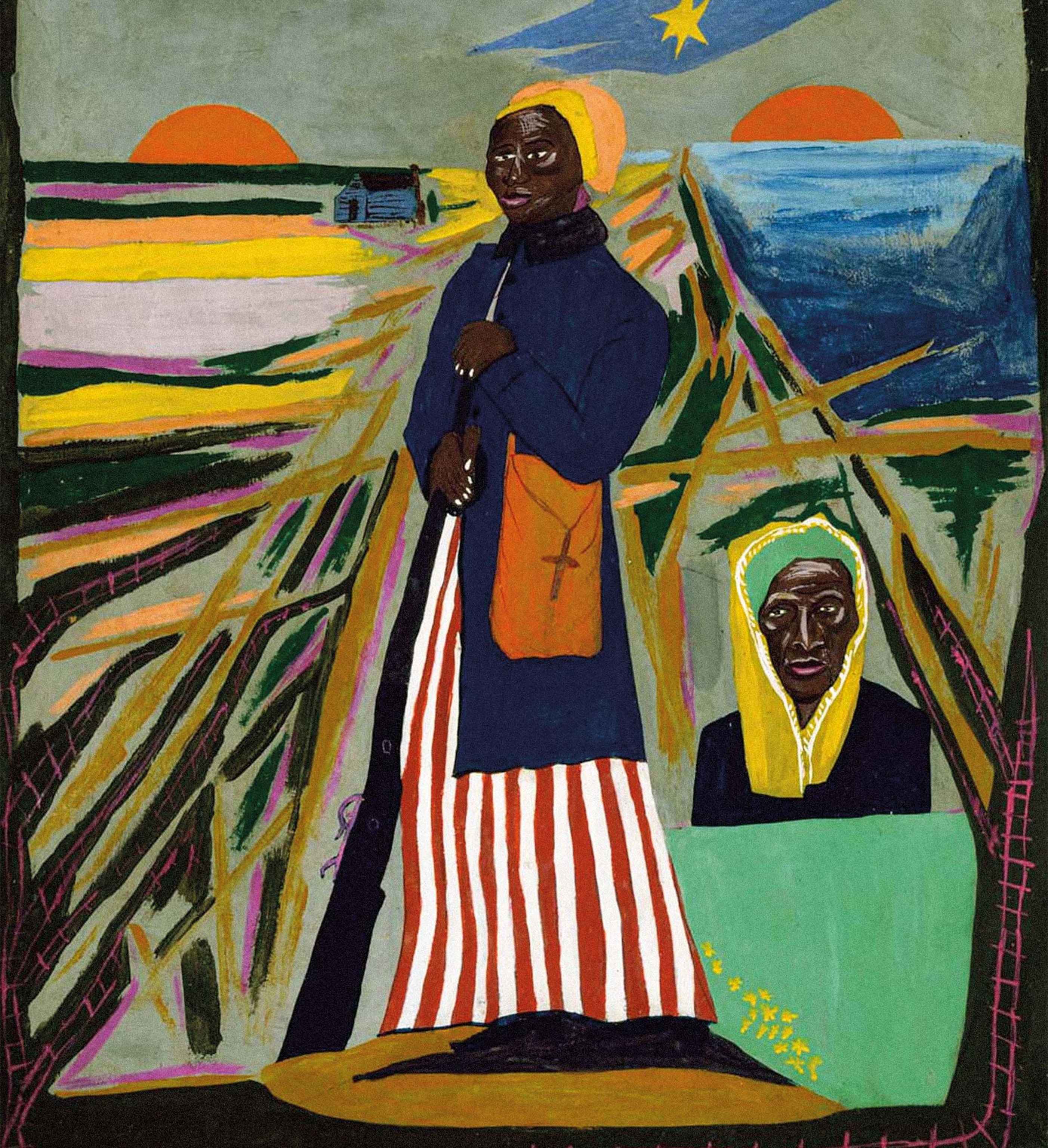

Dunant, too, stepped in: He helped order food, medicine, and bandages when supplies ran low. He was impressed by the dedication of local women who tended to the wounded—allies and enemies alike—repeating the words tutti fratelli: all are brothers.

Rouse yourselves from your lethargy, your culpable indifference ... There are fateful moments in history: do not let pass the auspicious time... Let not the end of the century slip away without a great popular peace movement springing up everywhere in favor of peace and the reduction of armaments... When you are in the majority, yours is the opinion which forms that of your governments... On this issue, your apathy is cowardice; your indifference, insanity; your opposition, laziness and ignorance. Wake up before it is too late.From Dunant’s 1889 pamphlet “The Proposal by Tsar Nicholas II”

A call to service

Seen through the prism of his upbringing, Dunant’s dramatic transition from businessman to humanitarian in the aftermath of Solferino is not altogether surprising. Born in 1828 to a staunchly Protestant, bourgeois family in Geneva—the adoptive city of the 16th-century Protestant reformer John Calvin—Dunant showed a deep religious vocation from childhood. His familiarity with Scripture became evident later in his life, when his writings exhorting peace took on the prophetic language of the Bible.

At age 18 he joined the Geneva Society for Alms Giving, and at age 19 he founded a Bible study group. He also encouraged the formation of the Geneva branch of the YMCA. From 1853 he focused on developing his business interests in Algeria but remained actively involved with religion.

The sense of purpose was a constant throughout his life, and on witnessing the dismal scenes in Italy in 1859, the 31-year-old Dunant suddenly saw what his vocation could be. Although deeply impressed by the attempts of ordinary people to care for the wounded, Dunant was shocked by the paralysis of local authorities. Dunant believed that with better organization, many lives could have been saved. From this moment on, his personal business interests took a back seat.

One of the first achievements in his activism was securing a meeting with the French military commander of the Italian campaign, Patrice de MacMahon, to discuss the unfolding humanitarian disaster in Castiglione.

Reflection and action

Dunant chronicled his experiences in his book A Memory of Solferino:

Wounds were infected by the heat and dust, by shortage of water and lack of proper care, and grew more and more painful. Foul exhalations contaminated the air ... The convoys brought a fresh contingent of wounded men into Castiglione every quarter of an hour, and the shortage of orderlies was cruelly felt.

In addition to this eyewitness account of the havoc, the best-selling book made two proposals that would bring future relief to people all over the world, both combatants and civilians.

The first was to establish aid organizations that could be ready to intervene as soon as armed conflict broke out. The second was to set up an international agreement that would guarantee assistance to those wounded in battle. Promoting these radical proposals became Dunant’s defining mission. He dispatched copies of the book to political and military leaders across Europe.

(Meet the man who took it one step further: the inventor of the Bloodmobile.)

Gathering of the nations

Dunant needed operational help to take the project to the next stage. Following the publication of A Memory of Solferino, a Swiss jurist named Gustave Moynier stepped into Dunant’s life.

Moynier had been deeply impressed by Dunant’s book. It was largely thanks to Moynier’s leadership that, in fall 1863, 16 European states came to Geneva to discuss Dunant’s proposal for an international aid organization.

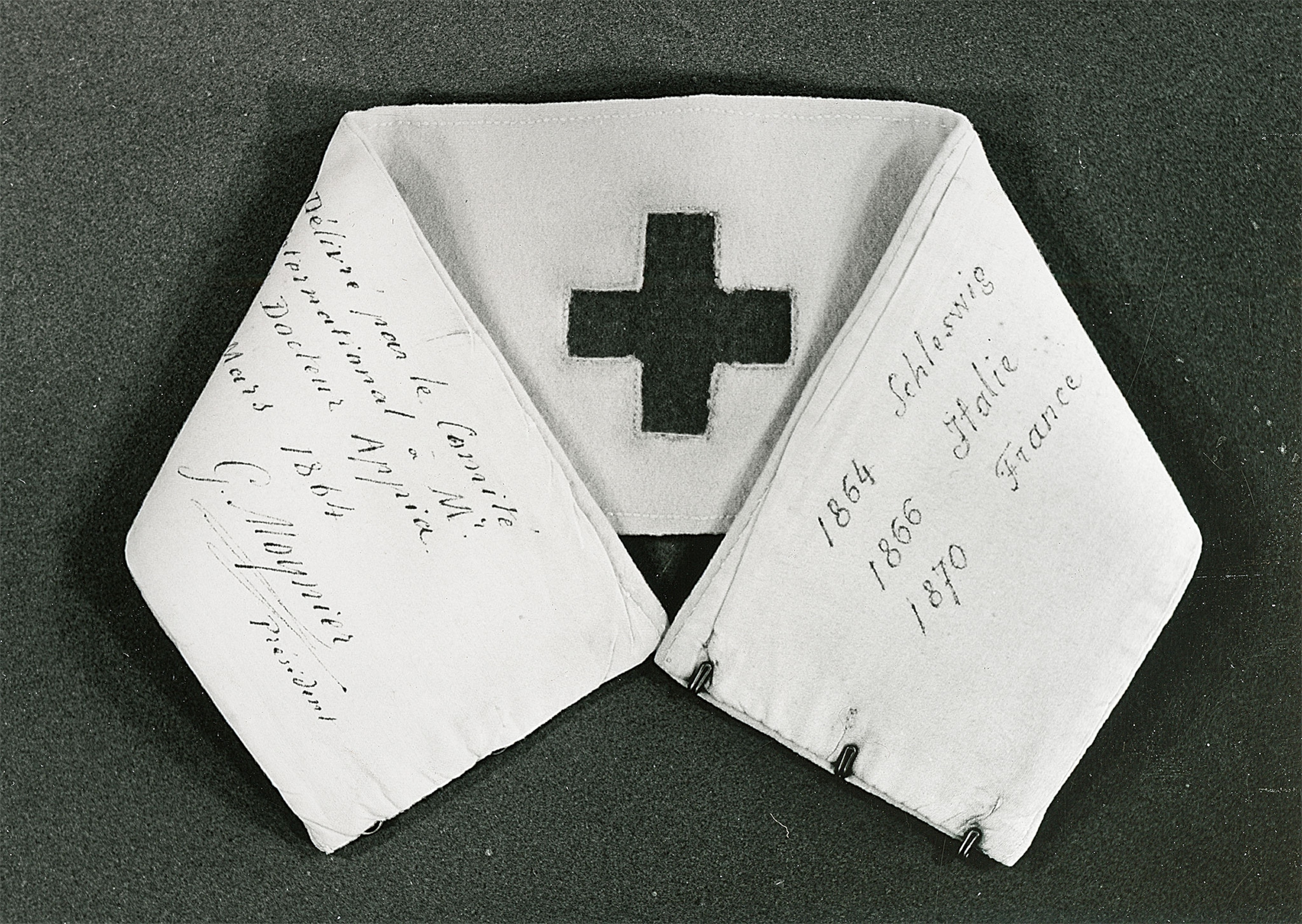

Reaching an agreement was difficult. Nevertheless, the conference closed with a call for committees to be created in each country, ready to act in times of war. Members of the aid committees were to be identified by an armband whose colors were the reverse of the Swiss flag: a white background bearing a red cross. The latter symbol eventually gave the organization its name.

Central to the global success of the Red Cross are the agreements by which states respect the neutrality of its operatives. Dunant’s key idea—that humanitarianism must be codified in international law—led the Swiss government to organize another conference in 1864.

In that penultimate year of the American Civil War, Europeans were all too aware that modern combat was becoming increasingly costly in terms of the numbers of dead and wounded. The conference concluded with 12 European states signing an agreement centering on three key resolutions: the protection of hospitals in war zones; the right to treatment for all combatants; and the protection of civilians providing medical aid. The First Geneva Convention had been born (to be followed, over the next century, by three more conventions). In parallel, the work of the International Committee of the Red Cross expanded to virtually all parts of the globe, later inspiring a counterpart, the Red Crescent Society, in Muslim-majority countries.

While Dunant’s creation thrived, his business in Algeria collapsed. He was condemned for fraudulent bankruptcy and expelled from the Red Cross. Plunged into obscurity, Dunant wasn’t rehabilitated until 1901, when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize nine years before his death. The wars of the 20th and 21st centuries were as deadly as he feared, with civilians drawn increasingly into the line of fire. All over the world today, war-stricken populations receive relief from terrible suffering thanks to the vision of a man moved with compassion on an Italian battlefield over 160 years ago.

(The explosive origins of the Nobel Prizes.)