New Year’s resolutions aren’t a fad—they have endured for thousands of years

From Babylonian kings to 21st-century gym memberships, the tradition of starting fresh on January 1 has ancient roots—and surprisingly familiar goals.

Every January 1, millions of people set intentions to exercise more, spend less, or be kinder—a ritual that feels deeply modern but has surprisingly ancient roots. The tradition of making New Year’s resolutions stretches back nearly 4,000 years, originating with civilizations that marked the new year as a time of renewal and reflection. “The desire to start fresh is a human impulse,” says Candida Moss, a University of Birmingham professor specializing in ancient history and early Christianity.

From vows made by Babylonian kings to the personal promises of today, the practice has evolved, but its core remains strikingly familiar: welcoming a new year with the hope of becoming better.

The ancient origins of New Year’s resolutions

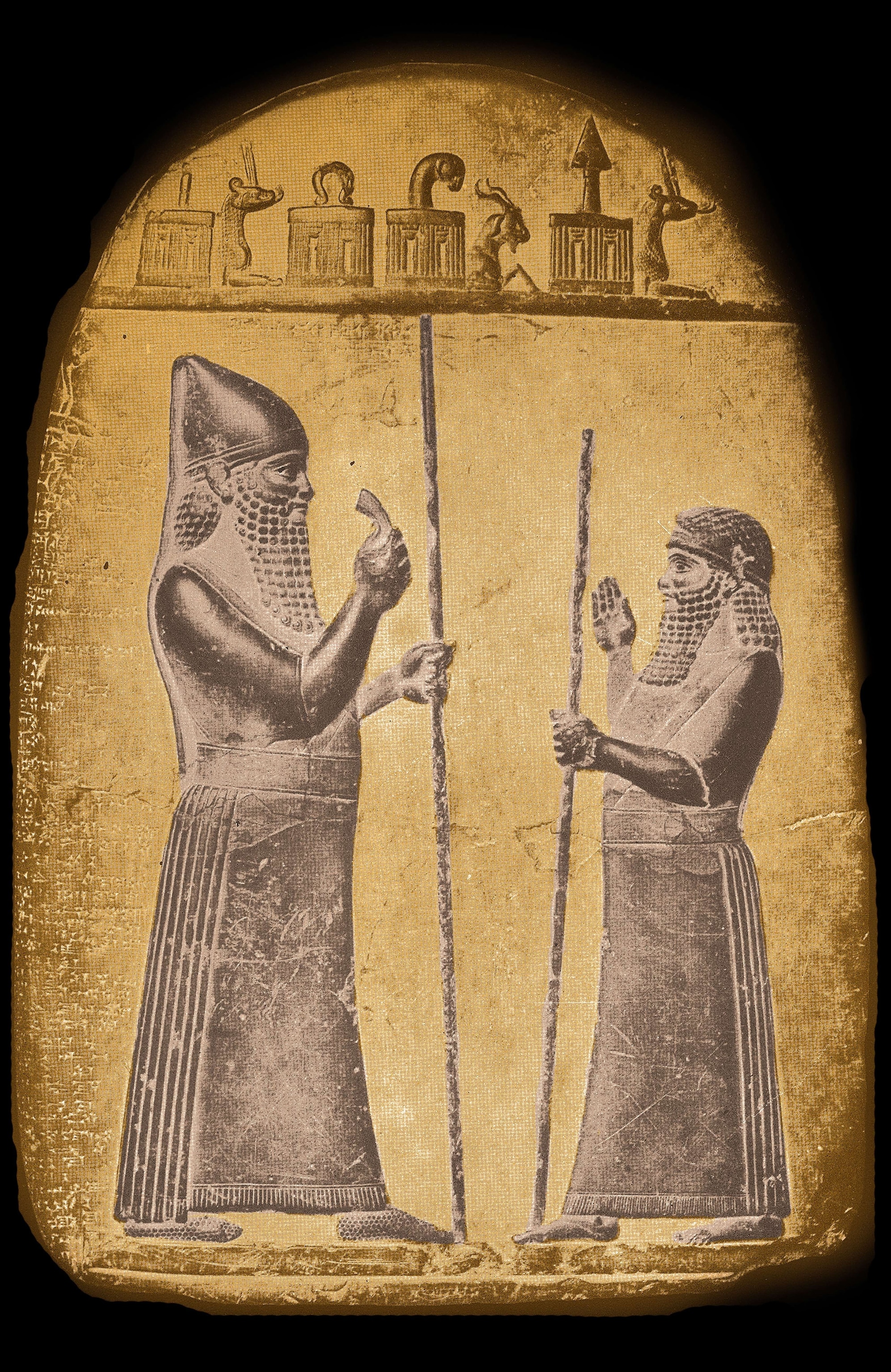

The Babylonians were among the first civilizations to celebrate the start of a new year, marking the occasion with festivals and rituals. “There is a lot of written documentation about New Year festivals in ancient Babylonia, Syria, and other places in Mesopotamia tied to the notion of the start of the new year,” says Eckart Frahm, a professor of Near Eastern languages and civilizations at Yale University.

These festivals, often tied to the spring equinox, centered around expressing gratitude to the gods for a bountiful harvest, says Frahm, not resolution-making. Keeping these vows was no trivial matter—fulfilling them was believed to secure divine favor for the year ahead, while breaking them risked the wrath of the gods.

(When is the right time to start a new habit—and actually keep it?)

However, in the late first millennium B.C., a Babylonian king publicly vowed to be a better ruler. This act, sometimes referred to as a “negative confession,” was not simply a personal reflection but a public declaration of accountability. Scholars debate whether this event actually occurred or if the story was influenced by dissent within the priestly class. Nevertheless, this tradition laid the groundwork for what we now know as New Year’s resolutions.

While the Babylonians may have conceived the idea, the Romans cemented January 1st as the beginning of the new year. Like the Babylonians, they celebrated with festivals and rituals, but the Romans also incorporated practical elements of renewal, including “supernatural spring cleaning” and vows of renewal. “These traditions focused on starting the year on the right foot: cleaning homes, stocking the pantry, paying off debts, and returning borrowed items,” says Moss.

Familiar goals, fresh framing

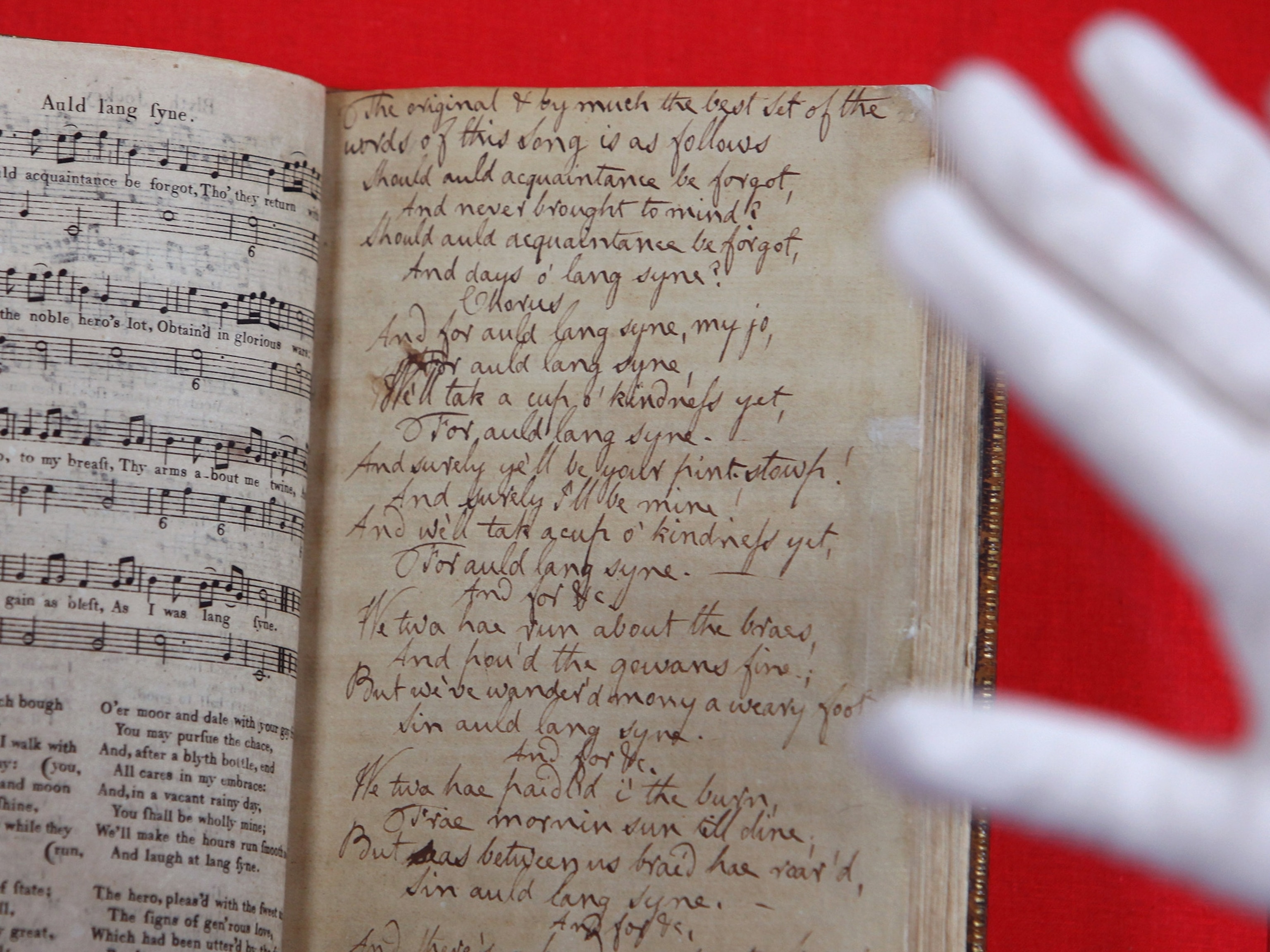

Centuries later, the tradition crossed the Atlantic to Colonial America, where the Puritans embraced introspection over revelry. “There was a desire to avoid debauchery and reflect on the passing and coming years. This period marked the emergence of resolutions in a modern sense,” Moss says.

Alexis McCrossen, a history professor at Southern Methodist University, says that during this time, it was common for churches to have a “Sabbath sermon,” which took place on the first Sunday of the year. These sermons (including a famous one by Thomas Foxcroft in 1724) often emphasized that time is fleeting and congregants should be a better servants of God.

(The secret to thriving in the winter? Embrace it, don’t fight it.)

Diaries from early America reveal individuals pledging to overcome sin or abstain from alcohol, frequently using phrases like “I resolve myself” or “I’m resolved to do,” says McCrossen. New England theologian Jonathan Edwards embodied this introspective spirit, creating 70 resolutions over several years, including “never to speak evil of any, except I have some particular good call for it,” or in essence, “to stop gossiping,” Moss says.

By the 19th century, New Year’s resolutions had transcended their Christian origins. “Today, resolutions are largely secular, reflecting the broader secularization of society,” Moss says.

Why the tradition continues

Newspaper articles throughout the 1900s show how little New Year’s resolutions people make have changed over time. A New Year’s Eve article from 1912 in The Sacramento Star reads that New Year’s resolutions are a time to swear off bad habits.

(Here are eight strategies to make your New Year’s resolutions stick.)

In 1938, The Miami Daily News encouraged female readers to keep resolutions small and manageable, warning against “glittering resolutions which you know in your heart are as brittle as Christmas tree ornaments, wedding vows, or campaign promises.”

The idea that New Year’s resolutions don’t work has been well-recorded in newspapers over the years, too. An article published in the Fort Myers News-Press on December 30, 1937, featured psychologists saying that New Year’s resolutions don’t work. In 1941, The Afro-American Times ran an article on January 4 stating that most people don’t make resolutions because they’re never kept—which may be why only three in 10 Americans report making any resolutions in 2024.